Hanging Rock, Victoria

| Hanging Rock[1] | |

|---|---|

| |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 718 m (2,356 ft) [2]AHD |

| Prominence | 105 metres (344 ft) above plain [2] |

| Coordinates | 37°19′49″S 144°35′42″E / 37.330222°S 144.595083°ECoordinates: 37°19′49″S 144°35′42″E / 37.330222°S 144.595083°E |

| Geography | |

| Parent range | Macedon |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 6.25 million years |

| Mountain type | Mamelon |

Hanging Rock (also known as Mount Diogenes, Dryden's Rock,[6] and to some of its traditional owners as Ngannelong[7]) is a distinctive geological formation in central Victoria, Australia. A former volcano, it lies 718m above sea level (105m above plain level) on the plain between the two small townships of Newham and Hesket, approximately 70 km north-west of Melbourne and a few kilometres north of Mount Macedon.

In the middle of the 19th century, the traditional occupants of the place – tribes of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung and Taungurung – were forced from it.[8] They had been its occupants for, potentially, thousands of years[9] and, colonisation notwithstanding, have continued to maintain cultural and spiritual connections with the place.[7]

To the settler colonialist society, Hanging Rock became a place for recreation and tourism. It came alternately under private, government, and mixed public-private control.[10]

In the late 20th century, the area became very widely known as the setting of Joan Lindsay's novel Picnic at Hanging Rock.

Geology

Hanging Rock is a mamelon, created 6.25 million years ago by stiff magma pouring from a vent and congealing in place. Often thought to be a volcanic plug, it is not. Two other mamelons exist nearby, created in the same period: Camels Hump, to the south on Mount Macedon and, to the east, Crozier's Rocks. Alternative names for Crozier's Rocks are Brock's Monument, Alexander's Head and Mount Crystal. All three mamelons are composed of soda trachyte. As Hanging Rock's magma cooled and contracted it split into rough columns. These weathered over time into the many pinnacles that can be seen today.

The significance of these three mamelons demonstrates the mechanism of plate tectonics. As the Australian Plate moved northwards towards East Asia, over a period of 27 million years it passed over a volcanic hotspot. This resulted in a chain of volcanoes stretching from Hillsborough (33 million years ago) in Northern Queenland to Hanging Rock (6.5 million years ago) which is part of the southernmost end of this volcanic activity. This chain also includes the Warrumbungles (New South Wales, 15.5 million years ago) and the Glass House Mountains (Southern Queensland, 24.3 million years ago). These volcanoes all have the same chemical composition.[11] [12][13]

Hanging Rock contains numerous distinctive rock formations, including the "Hanging Rock" itself (a boulder suspended between other boulders, under which is the main entrance path), the Colonnade, the Eagle and the UFO. The highest point on Hanging Rock is 718 metres above sea level and 105 metres above the plain below.

Traditional owners and colonisation

At the time of colonisation, the traditional occupants had lived around Hanging Rock for more than 26,000 years. The Rock was woven into the fabric of the culture of the traditional owners. However, they were forcibly displaced from the area.[8] Jason Tamiru has expressed a Yung Balug perspective on this history:

The truth is my people were hit hard during the frontier wars. The Western region is known to us as the Killing Fields. The naming of the Rock is with all those that come in my dreams. Australia is starting to learn that there is a black history in this country that needs to be acknowledged and celebrated.

Long before the 1967 novel, 1975 film and the naming of Hanging Rock, Tribes of the Dja Dja Wurrung, Woi Wurrung and Taungurung would gather at that location for important Men’s Ceremony.

This is a place where big business was held: Corrobborees, Initiation Ceremonies, Songline Ceremonies, trade and relationship building and a place where laws were made and passed.[7]

According to Tamiru, Ngannelong continues to play a role in Yung Balug culture:

The mystique and spiritual essence of the rock has contributed to the story of our Dreaming which binds my people to our creator spirits and country.

We Sing, Dance and Paint our Country forever.[7]

Settler colonialists dispossessed the Aboriginal owners and forced them out of the area.[8] "One of the last initiation ceremonies may have been held there in November 1851 by a Wurundjeri elder from the Templestowe area" in the Yarra Valley.[6] This ceremony was also attended by two young settlers' children, Willie Chivers, 11, and his younger brother Tom, 7, who were being cared for on a daily basis by the tribe after their mother had died. Their father went missing after looking for their mother.

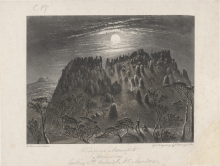

An engraving made by William Blandowski in 1855/56 shows a group of Aboriginal people camped on the hillside.[14] Another engraving by Robert Bruce published in a 1865 edition of The Illustrated Melbourne Post shows three Aboriginal figures in the foreground with Hanging Rock rising up in the background.[6]

Names

Attempts to uncover Hanging Rock's Aboriginal name have proven difficult. Some think it is "Anneyelong" because of an inscription underneath an engraving of the rock made by German naturalist, William Blandowski, during an expedition in 1855-56. Historian and toponymist Ian D. Clark believes Blandowski misheard the name, and the word was possibly "Ngannelong" or something similar.[8]The name "Diogenes Mount" was bestowed on the rock by the surveyor Robert Hoddle in 1843[15] in keeping with the spirit of several ancient Macedonian names given by Major Thomas Mitchell during his expedition through Victoria in 1836, which passed close to Hanging Rock. Others include Mount Macedon, Mount Alexander and the Campaspe River.[16] Six other European names (Mount Diogenes, Diogenes' Head, Diogenes Monument, Dryden's Rock, Dryden's Monument and Hanging Rock) have also been recorded for the site.[6]

Community

Horse races have been held at Hanging Rock for over one hundred years;[10] the Hanging Rock Racing Club holds two race meetings a year on New Year's Day and Australia Day (26 January).[17]

The Friends of Hanging Rock, established in 1987, is a community group which holds events open to the public, such as planting days and wildlife tours.[18]

In 2013, the Hanging Rock Action Group was formed by local residents to call for adequate community consultation about the Macedon Ranges Shire Council's proposal to build a 200-person conference centre and 100 bed hotel in the Eastern Paddock, adjacent to and very visible from the Rock. The anger by the local community over this issue[19] led to 7 of 9 councillors being voted out in the following elections.

Hanging Rock is the centrepiece for the Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve, a public reserve managed by the Macedon Ranges Shire Council. The reserve includes a horse racing track, picnic grounds, creek, interpretation centre and cafe. The reserve is a habitat for endemic flora and fauna, including koalas, wallabies, possums, phascogales, wedge-tailed eagles and kookaburras.

The reserve is open to the public during daylight hours seven days a week. Entry is charged per vehicle. Camping is possible by arrangement.

Hanging Rock Reserve is listed on the Victorian Heritage Register as a place of historical, aesthetic and social significance to the State of Victoria.[20]

Hanging Rock Reserve is currently under review by the Department of Environment, Land, Water and Planning to determine future governance and administrative arrangements for management of the site.[21]

Treatments in novel and film

Hanging Rock was the inspiration and setting for the novel Picnic at Hanging Rock, written by Joan Lindsay and published in 1967. The novel dealt with the disappearance of a number of schoolgirls during a visit to the site. Their disappearance was explained in the final chapter, but Lindsay deleted this chapter at the suggestion of her editor, thinking the mystery was greater without it.

The novel inspired the film Picnic at Hanging Rock, made in 1975 and directed by Peter Weir. The success of the film was responsible for a substantial increase in visits to the rock and a renewal of interest in the novel. Yvonne Rousseau wrote a book called The Murders at Hanging Rock, published in 1980, which examined possible explanations for the disappearance of the girls.

The deleted final chapter of the novel was finally published in 1987 after the death of Joan Lindsay. Lindsay had given the copyright for the last chapter to her literary agent John Taylor on the understanding he would only publish it after her death. It was titled The Secret of Hanging Rock.

Concert venue

Hanging Rock reserve is currently used as an occasional outdoor concert venue by major international acts on the Australian leg of their tours.

The following events have taken place at Hanging Rock as part of a trial by Frontier Touring and the Macedon Ranges Shire Council:[22]

- Leonard Cohen – November 2010

- Rod Stewart – February 2012

- Bruce Springsteen – March 2013 (Wrecking Ball tour)

In 2014 the Rolling Stones were scheduled to play a night concert (30 March) at Hanging Rock as part of their "14 On Fire" tour. The death of Mick Jagger's partner, L'Wren Scott, resulted in the postponement of the entire tour. The tour was rescheduled and resumed in Adelaide on October 25, 2014. The Hanging Rock concert was rescheduled to take place on Saturday, November 8, 2014, but Rolling Stones lead Mick Jagger cancelled the concert due to a throat infection.[23]

In October 2013 Frontier Touring signed a five-year agreement with the Macedon Ranges Shire Council to hold up to four concerts per year at Hanging Rock, effective from 31 October 2014.[24]

Subsequent concerts have been:

- The Eagles – February 2015 (History of the Eagles)

- Rod Stewart – March 2015

- Cold Chisel – November 2015

- Ed Sheeran – February 2017

- Bruce Springsteen – February 2017

Gallery

- Entrance to Hanging Rock

- Rock formations

- Engraving from 1866 near the summit

View from Hanging Rock

View from Hanging Rock

See also

References

- ↑ "THE HANGING ROCK, NEAR WOODEND". Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil. IV (51). Victoria, Australia. 17 February 1877. p. 182. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 "About Hanging Rock". Macedon Ranges Tourism. Retrieved 2014-11-08.

- ↑ "THE HANGING ROCK, NEAR WOODEND". Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil. IV (51). Victoria, Australia. 17 February 1877. p. 182. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE HANGING ROCK, NEAR WOODEND". Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil. IV (51). Victoria, Australia. 17 February 1877. p. 182. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- ↑ "THE HANGING ROCK, NEAR WOODEND". Australasian Sketcher with Pen and Pencil. IV (51). Victoria, Australia. 17 February 1877. p. 182. Retrieved 30 March 2017 – via National Library of Australia.

- 1 2 3 4 Stephanie Skidmore & Ian D. Clark (2014) "Hanging Rock Recreation Reserve", In: An Historical Geography of Tourism in Victoria, Australia: Case Studies, Ian D. Clarke ed., De Gruyter Open Ltd: Warsaw/Berlin, pp. 111-134.

- 1 2 3 4 "Jason Tamiru / The Yung Balug perspective of Hanging Rock · Malthouse Theatre". malthousetheatre.com.au. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- 1 2 3 4 "What Really Happened at Hanging Rock". Vice. 2017-02-03. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ↑ "Hanging Rock History". Hanging Rock - A History. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- 1 2 "THE HISTORY OF HANGING ROCK". www.hangingrock.info. Retrieved 2018-02-21.

- ↑ McConville, Chris (2017). Hanging rock : a history (First ed.). Woodend, Vic.: Friends of Hanging Rock Inc. p. 65. ISBN 9780648166603. OCLC 1011492509.

- ↑ Wellman, P. (20 July 1983). "Hotspot Volcanism in Australia and New Zealand: Cainozoic and Mid-Mesozoic". Tectonophysics. Volume 96, Issues 3–4: 225–43 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Wellman, P. McDougall, I. (July 1974). "Cainozoic igneous activity in eastern australia". Tectonophysics. Volume 23, Issues 1–2: Pages 49-65 – via Elsevier ScienceDirect.

- ↑ Mackay, M. (2011). "Singularity and the Sublime in Australian Landscape Representation". Literature & Aesthetics. 8: 121. As quoted in Skidmore and Clark, p. 113.

- ↑ McConville, Chris (2017). Hanging rock : a history (First ed.). Woodend, Vic.: Friends of Hanging Rock Inc. pp. 53, 58–59. ISBN 9780648166603. OCLC 1011492509.

- ↑ Duncan, J.S, ed. (1982). Atlas of Victoria. Victorian Government Printing Office. p. 74. ISBN 0-7241-8255-1.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

- ↑ "Friends of Hanging Rock – We work to restore and preserve Hanging Rock". Friendsofhangingrock.org. 2015-02-05. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ http://www.abc.net.au/am/content/2014/s3956948.htm

- ↑ "VHD". Vhd.heritagecouncil.vic.gov.au. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "Hanging Rock Review – DELWP". Web.archive.org. 2015-06-17. Archived from the original on 2015-09-12. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "Springsteen wrecks Hanging Rock". Theage.com.au. 2013-03-31. Retrieved 2017-03-29.

- ↑ "Hanging Rock Show Cancelled". rollingstones.com. November 6, 2012. Retrieved 2012-11-08.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2014-04-13. Retrieved 2014-04-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hanging Rock. |