Haida people

| X̱aayda, X̱aadas, X̱aad, X̱aat | |

|---|---|

Flag of the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN) | |

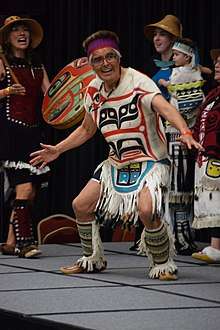

A Haida dances in full regalia. | |

| Total population | |

| c. 2,500+[1] | |

| Canada | 3,471[1] |

| United States | unknown |

| Languages | |

| Haida, English | |

| Religion | |

| Haida, possibly Christianity and others | |

Haida (English: /ˈhaɪdə/, Haida: X̱aayda, X̱aadas, X̱aad, X̱aat) are a nation and ethnic group native to, or otherwise associated with, Haida Gwaii (a Canadian archipelago) and the Haida language. Haida language, which is an isolate language, has historically been spoken across Haida Gwaii and certain islands on the Alaska Panhandle, where it has been spoken for at least 14,000 years. Prior to the 19th century, Haida would speak a number of coastal First Nations languages such as Lingít, Nisg̱a'a and Sm'álgyax. After settlers' arrival and colonisation of the Haida through residential schools, few Haida speak X̱aayda/X̱aad kíl, though there are many efforts to revive the language.

The Haida national government, the Council of the Haida Nation (CHN), is based in the archipelago of Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands) in northern British Columbia, Canada. A group known as the Kaigani Haida live across the international border of the Dixon Entrance on Prince of Wales Island (Tlingit: Taan) in Southeast Alaska, United States; Taan was traditionally and still is in Lingít territory. The Kaigani Haida migrated there in the late 18th century. Haida have occupied Haida Gwaii since at least 14,000 BP. Pollen fossils and oral histories both confirm that Haida ancestors were present when the first tree, a Lodgepole pine, arrived at SG̱uuluu Jaads Saahlawaay, the westernmost of the Swan Islands located in Gwaii Haanas.[2]

In British Columbia, the term "Haida Nation" can refer both to Haida people as a whole and their government, the Council of the Haida Nation. While all people of Haida ancestry are entitled to Haida citizenship, the Kaigani are also part of the Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska government. [3][4] The Haida language has sometimes been classified as one of the Na-Dene group, but is usually considered to be an isolate.[5]

Haida society continues to produce a robust and highly stylized art form, a leading component of Northwest Coast art. While artists frequently have expressed this in large wooden carvings (totem poles), Chilkat weaving, or ornate jewellery, in the 21st century, younger people are also making art in popular expression such as Haida manga.

In June 2017, the first feature-length Haida-language film, The Edge of the Knife, was in production with an all-Haida cast. The actors learned some Haida for their performances in the film. Gwaii Edenshaw is the director and co-screenwriter.[6]

Location

Traditional Haida territory spans the current international boundary between British Columbia, Canada and Alaska, United States. Their heartland is the two large and many smaller islands known as Haida Gwaii, which means "island of the people" in Haida. This archipelago was surveyed in 1787 by Captain George Dixon of the British Navy, who named them after one of his ships, the Queen Charlotte, which was in turn named after Charlotte, queen consort of George III of the United Kingdom. The name "Queen Charlotte Islands" was subsequently "given back" to the Crown in a ceremony between the British Columbia government and the Council of the Haida Nation.

Haida also live in Southeast Alaska, particularly on the southern half of Prince of Wales Island in communities such as Hydaburg, and in large cities elsewhere in the region such as Ketchikan. Haida also live in various cities in mainland British Columbia and the western United States.

History

The Haida are known for their craftsmanship, trading skills, and seamanship. They are thought to have been warlike and to practise slavery. Canadian Museum of Civilization anthropologist Diamond Jenness has compared the tribe to Vikings.[7]

Oral histories and archaeological evidence indicate that the Haida have occupied Haida Gwaii for more than 17,000 years. In that time they have established an intimate connection with the islands' lands and oceans, established highly structured societies, and constructed many villages.[8][9] The Haida have also occupied present-day southern Alaska for more than the last 200 years, the modern group having emigrated from Haida Gwaii in the 18th century.

The Haida conducted regular trade with Russian, Spanish, British, and American fur traders and whalers. According to sailing records, they diligently maintained strong trade relationships with Westerners, coastal people, and among themselves.[10]

Like other groups on the Northwest Coast, the Haida defended themselves with fortifications, including palisades, trapdoors and platforms. They took to water in large ocean-going canoes, big enough to accommodate as many as 60 paddlers, each created from a single Western red cedar tree. The aggressive tribe were particularly feared in sea battles, although they did respect rules of engagement in their conflicts.[7] The Haida developed effective weapons for boat-based battle, including a special system of stone rings weighing 18 to 23 kg (40 to 51 lb) which could destroy an enemy's dugout canoe and be reused after the attacker pulled it back with the attached cedar bark rope. The Haida took captives from defeated enemies. Between 1780 and 1830, the Haida turned their aggression towards European and American traders. Among the half-dozen ships the tribe captured were the Eleanor and the Susan Sturgis. The tribe made use of the weapons they so acquired, using cannons and canoe-mounted swivel guns.[7]

In 1856, an expedition in search of a route across Vancouver Island was at the mouth of the Qualicum River when they observed a large fleet of Haida canoes approaching and hid in the forest. They observed these attackers holding human heads. When the explorers reached the mouth of the river, they came upon the charred remains of the village of the Qualicum people and the mutilated bodies of its inhabitants, with only one survivor, an elderly woman, hiding terrified inside a tree stump.[11]

Also in 1857, the USS Massachusetts was sent from Seattle to nearby Port Gamble, where indigenous raiding parties made up of Haida (from territory claimed by the British) and Tongass (from territory claimed by the Russians) had been attacking and enslaving the Coast Salish people there. When the Haida and Tongass (sea lion tribe Tlingit) warriors refused to acknowledge American jurisdiction and to hand over those among them who had attacked the Puget Sound communities, a battle ensued in which 26 natives and one government soldier were killed. In the aftermath of this, Colonel Isaac Ebey, a US military officer and the first settler on Whidbey Island, was shot and beheaded on 11 August 1857 by a small Tlingit group from Kake, Alaska, in retaliation for the killing of a respected Kake chief in the raid the year before. Ebey's scalp was purchased from the Kake by an American trader in 1860.[12][13][14][15] The introduction of smallpox among the Haida at Victoria in March 1862 significantly reduced their sovereignty over their traditional territories, and opened the doorway to colonial power.[16] As many as nine in ten Haidas died of smallpox and many villages were completely depopulated.

In 1885 the Haida potlatch (Haida: waahlgahl) was outlawed under the Potlatch Ban. The elimination of the potlatch system destroyed financial relationships and seriously interrupted the cultural heritage of coastal people.

The Haida also created "notions of wealth", and Jenness credits them with the introduction of the totem pole (Haida: ǥyaagang) and the bentwood box.[7] Missionaries regarded the carved poles as graven images rather than intimate representations of the family histories that wove Haida society together. Chiefly families showed their histories by erecting totems outside their homes, or on house posts forming the building. Their social organization was matrilineal.[17] As the islands were Christianized, many cultural works such as totem posts were destroyed or taken to museums around the world. This significantly undermined Haida self-knowledge and further diminished morale.

The government began forcibly sending some Haida children to residential schools as early as 1911. Haida children were sent as far away as Alberta to live among English-speaking families where they were to be assimilated into the dominant culture.

Villages

Historical Haida villages were:[18]

- Kiusta

- Kung

- Yan

- Hiellan

- Skidegate (Graham Island)

- Cha'atl

- Haina

- Kaisun (Haida: Ḵaysuun Llnagaay[19])

- Cumshewa (Moresby Island)

- Skedans aka Koona or Q'una.

- Tanu (New Clew), Louise Island

- Ninstints (Sgang Gway, aka Anthony Island)

- Masset The name Masset, received from pre British contact between Haidas and the Spanish, actually includes three separate and adjoining communities,

- Atewaas (Old Massett)

- Jaahguhl

- Kayung

- Hlk'yah GaawGa (Windy Bay) (Lyell Island)[20]

- Klinkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Sukkwan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Howkan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Kasaan (Kaigani Haida, Prince of Wales Island)

- Tlell, British Columbia

- Dadens, Langara Island

Calendar

The Haidas' calendar:

- April/May- Gansgee 7laa kongaas

- May/Early June- Wa.aay gwaalgee

- June/July- Kong koaas

- July/August- Sgaana gyaas

- August/September- K'ijaas

- September/October- K'alayaa Kongaas

- October/November- K'eed adii

- November/December- Jid Kongaas

- December/January- Kong gyaangaas

- January/February- Hlgiduum kongaas

- February/March- Taan kongaas

- March- Xiid gayaas

- April- Wiid gyaas

Ethnobotany

They use the berries of Vaccinium vitis-idaea ssp. minus as food.[21]

Notable Haida

- Primrose Adams, artist

- Delores Churchill, artist, basketweaver

- Marcia Crosby, art historian

- Cumshewa, chief

- Florence Davidson, artist and memoirist

- Reg Davidson, carver

- Robert Davidson, carver

- Freda Diesing, carver

- Charles Edenshaw, carver, jeweler and painter

- Guujaaw (Gary Edenshaw), artist and politician, former President of the Council of the Haida Nation

- Dorothy Grant, artist, fashion designer

- Jim Hart, hereditary chief of Stasstas Eagle Clan, artist

- Koyah, chief

- Gerry Marks, artist

- Bill Reid, carver, sculptor and jeweler

- Jay Simeon, artist

- Skaay, mythteller

- Michael Nicoll Yahgulanaas, artist

Anthropologists and scholars

This is an incomplete list of anthropologists and scholars who have done research on the Haida.

- Marius Barbeau

- Robert Bringhurst

- Emily Carr

- Gillian Crowther

- Kathleen E. Dalzell

- Wilson Duff

- John Enrico

- Daryl Fedje

- Christie Harris

- Bill Holm

- Robert Bruce Inverarity

- Marianne Boelscher Ignace

- Clealls John Medicine Horse Kelly

- George Peter Murdock

- Charles F. Newcombe

- Frances Poole

- Mary Lee Stearns

- John R. Swanton

- Elvira Stefania Tiberini

- Nancy J. Turner

- Dan Vaughan

- Frederick White

See also

References

- 1 2 History of the Haida Nation, Council of the Haida Nation website. Skidegate and Old Masset combined are 1,471 combined, and 2,000 more Haida live in Vancouver and Prince Rupert and elsewhere.

- ↑ Fedje, Daryl (2005). Haida Gwaii: Human History and Environment from the Time of Loon to the Time of the Iron People (1 ed.). Vancouver, Toronto: UBC Press. p. 128. ISBN 9780774809221. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Haida Nation" (PDF). haidanation.ca. Haida Nation. Retrieved 26 June 2018.

- ↑ "Central Council Tlingit Haida Indian Tribes of Alaska". CCTHITA. Retrieved 2016-06-23.

- ↑ Schoonmaker, Peter K.; Bettina Von Hagen; Edward C. Wolf (1997). The Rain Forests of Home: Profile Of A North American Bioregion. Island Press. p. 257. ISBN 1-55963-480-4.

- ↑ Catherine Porter, "A Language Nearly Lost Is Revived in a Script", New York Times, 12 June 2017, p. 1

- 1 2 3 4 "Warfare". Canadian Museum of Civilization. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- ↑ Hume, Mark (20 July 2012). "When did the first people arrive in the Americas?". The Globe and Mail. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "Caves reveal thousands of years of history". Queen Charlotte Islands Observer. 14 September 2007. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "Canoes and Trade". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ Elms p 20, citing William Wyford Walkem, Stories of Early British Columbia, "Adam Horne's trip across Vancouver Island" (Vancouver, BC: Published by News Advertiser, 1914) p 41.

- ↑ Puget Sound Herald Nov 19, 1858

- ↑ Juneau Empire, February 29, 2008

- ↑ Beth Gibson, Beheaded Pioneer, Laura Arksey, Columbia, Washington State Historical Society, Tacoma, Spring, 1988.

- ↑ Bancroft says they were Stikines, a Tlingit subgroup, and makes no mention of the Haida. History of Washington, Idaho, and Montana: 1845–1889, p.137 Hubert Howe Bancroft (1890) This enormous source, photocopied, including p.137, is more easily accessible online at , if desired. Retrieved 2012-2-21.

- ↑ "The Spirit of Pestilence". The University of Victoria. Retrieved 14 January 2014.

- ↑ "Social Organization". Canadian Museum of History. Retrieved 8 March 2017.

- ↑ Canadian Museum of Civilization webpage on Haida villages

- ↑ "FirstVoices: Hlg̱aagilda X̱aayda Kil : words". Retrieved 2012-07-08.

- ↑ Parks Canada website Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Compton, Brian Douglas, 1993, Upper North Wakashan and Southern Tsimshian Ethnobotany: The Knowledge and Usage of Plants..., Ph.D. Dissertation, University of British Columbia, page 101

General sources

- Macnair, Peter L.; Hoover, Alan L.; Neary, Kevin (1981). The Legacy: Continuing Traditions of Canadian Northwest Coast Indian Art

Further reading

- Blackman, Margaret B. (1982; rev. ed., 1992) During My Time: Florence Edenshaw Davidson, a Haida Woman. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- Boelscher, Marianne (1988) The Curtain Within: Haida Social and Mythical Discourse. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press.

- Bringhurst, Robert (2000) A Story as Sharp as a Knife: The Classical Haida Mythtellers and Their World. Douglas & McIntyre.

- Donald, Leland (1997) Aboriginal Slavery on the Northwest Coast of North America. University of California Press.

- Andersen, Doris (1974) Slave of the Haida. Macmillan Co. of Canada.

- Kushner, Howard (1975) Conflict on the Northwest Coast: American-Russian Rivalry in the Pacific Northwest. Greenwood Press.

- Black, Lydia T.; Dauenhauer, Nora; Dauenhauer, Richard (2008), Anóoshi Lingít Aaní Ká/Russians in Tlingit America: The Battles of Sitka, 1802 and 1804, University of Washington Press, ISBN 978-0-295-98601-2 .

- Fisher, Robin (1992) Contact and Conflict: Indian-European Relations in British Columbia, 1774-1890. UBC Press.

- Geduhn, Thomas (1993) "Eigene und fremde Verhaltensmuster in der Territorialgeschichte der Haida." (Mundus Reihe Ethnologie, Band 71.) Bonn: Holos Verlag.

- Harris, Christie (1966) Raven's Cry. New York: Atheneum.

- Harrison, Charles (1925) Ancient Warriors of the North Pacific - The Haidas, Their Laws, Customs and Legends. H.F. & G. Witherby.

- Huteson, Pamela (2007) "Transformation Masks" Surrey, B.C. Canada: Hancock House Publishers LTD. ISBN 978-0-88839-635-8

- Kan, Sergei (1993) SYMBOLIC IMMORTALITY; The Tlingit Potlatch of the Nineteenth Century Smithsonian.

- Snyder, Gary (1979) He Who Hunted Birds in His Father's Village. San Francisco: Grey Fox Press.

- Stearns, Mary Lee (1981) Haida Culture in Custody: The Masset Band. Seattle: University of Washington Press.

- The Hydah mission, Queen Charlotte's Islands: an account of the mission and people, with a descriptive letter, Rev. Charles Harrison, publ. Church Missionary Society/Seeley, Jackson & Halliday, London, England, 1884.

- Yahgulanaas, Michael Nicoll (2008) "Flight of the Hummingbird" Vancouver; Greystone Books.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Haida. |