Great refractor

.jpg)

Great refractor refers to a large telescope with a lens, usually the largest refractor at an observatory with an equatorial mount. The preeminence and success of this style in observational astronomy was an era in telescope use[2] in the 19th and early 20th century.[2] Great refractors were large refracting telescopes using achromatic lenses (as opposed to the mirrors of reflecting telescopes). They were often the largest in the world, or largest in a region. Despite typical designs having smaller apertures than reflectors, Great refractors offered a number of advantages and were favored for astronomy.[2]

It was not until the 20th century that they were gradually superseded by large reflecting telescopes for professional astronomy. A great refractor was often the centerpiece of a new 19th century observatory, but was typically used with an entourage of other astronomical instruments such as a Meridian Circle, a Heliometer, and Astrograph, and a smaller refractor such as a Comet Seeker or Equatorial. Great refractors were often used for observing double stars and equipped with a Filar micrometer. Numerous discoveries of minor planets, satellites, the planet Neptune, and double stars were made, and pioneering work on astrophotography was done, with great refractors.[3]

Era of large refractors

The choice of building large refractors over reflectors was a technological one.[4] The difficulties of fabricating two disks of optical glass required to make a large achromatic lens were formidable. But reflecting telescopes had larger problems. The material their primary mirror was made of was speculum metal, a substance that only reflected up to 66 percent of the light that hit it and tarnished in months. They had to be removed, polished, and re-figured to the correct shape. This sometimes proved difficult, with the telescope mirrors sometimes having to be abandoned.[5] Because of this, large refractors seemed to be the better choice.

Although there had been very large (and unwieldy) Non-achromatic aerial telescopes of the late 17th century, and Chester Moore Hall and others had experimented with small achromatic telescopes in the 18th century, John Dollond (1706–1761) invented and created an achromatic object glass and lens which permitted achromatic telescopes up to 3–5 in (8–13 cm) aperture.[6][7] The Swiss Pierre Louis Guinand (1748–1824) discovered and developed a way to make much larger crown and flint glass blanks.[7] He worked with instrument maker Joseph von Fraunhofer (1787–1826) to use this technology for instruments in the early 19th century.[7]

The era of great refractors started with the first modern, achromatic, refracting telescopes built by Joseph von Fraunhofer in the early 1820s.[8][9][10][11] The first of these was the Dorpat Great Refractor, also known as the Fraunhofer 9-inch, at what was then Dorpat Observatory in the Governorate of Estonia (Estland) (which later became Tartu Observatory in southern Estonia). This telescope made by Fraunhofer had a 9 Paris inch (about 9.6 in (24 cm)) aperture achromatic lens and a 4 m (13.4 ft) focal length. It was also equipped with the first modern equatorial mount type called a "German equatorial mount" developed by Fraunhofer,[12] a mount that became standard for most large refractors from then on. A Fraunhofer 9-inch (24 cm) at Berlin Observatory was used by Johann Gottfried Galle in the discovery of Neptune.[13]

Refracting telescopes would quadruple in size by the end of the century, culminating with the largest practical refractor ever built, the Yerkes Observatory 40-inch (1 meter) aperture of 1895.[14][15] This great refractor pushed the limits of technology of the day; the fabrication of the two element achromatic lens (the largest lens ever made at the time), required 18 attempts and cooperation between Alvan Clark & Sons and Charles Feil of Paris.[15] To achieve its optical aperture it was actually slightly bigger physically, at 41 3/8 in.[16] Refractors had reached their technological limit; the problems of lens sagging from gravity meant refractors would not exceed around 1 meter,[17] although Alvan G. Clark, who had made the Yerkes 40-inch objective, said a 45-inch (114 cm) would be possible before he died.[16] In addition to the lens, the rest of the telescope needed to be a practical and high precision instrument, despite the size. For example, the Yerkes tube alone weighed 75 tons, and had to track stars just as accurately as a smaller instrument.[16]

The Great Paris Exhibition Telescope of 1900 was fixed in a horizontal position to overcome gravitational distortion on its 1.25 m (49.2 in) lens and was aimed with a 2 m siderostat. This demonstration telescope was scrapped after the Exposition Universelle closed.

End of the era

The era slowly came to end as large reflecting telescopes superseded the great refractors. In 1856–57, Carl August von Steinheil and Léon Foucault introduced a process of depositing a layer of silver on glass telescope mirrors. Silvered glass mirrors were a vast improvement over speculum metal and made reflectors a practical instrument. The era of large reflectors had begun, with telescopes such as the 36-inch (91 cm) Crossley Reflector (1895), 60-inch (1.5 m) Mount Wilson Observatory Hale telescope of 1908, and the 100-inch (2.5 m) Mount Wilson Hooker telescope in 1917.[18] (See also)

Examples

Great refractors were admired for their quality, durability, and usefulness which correlated to features such as lens quality, mount quality, aperture, and also length. Length was important because unlike reflectors (which can be folded and shorted), the focal length of glass lens correlated to the physical length of the telescope and offered some optical and image quality advantages.

Aperture

The progression of largest refracting telescopes in the 19th century, including some telescopes at private observatories that were not really used very much or had problems.[19][20]

| Selected Largest 19th Century Great Refractors by Year[21] | |||||||

| Observatory | Aperture | Year(s) | Lens Maker | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dorpat Observatory | 24 cm | 1826 | Fraunhofer | ||||

| Kensington Observatory | 30 cm | 1829–1838 | Cauchoix | Defunct 1836[22] or 1838[23] | |||

| Markree Observatory | 34 cm | 1834 | Cauchoix | [24] | |||

| Pulkovo observatory | 38 cm | 1839 | Merz and Mahler[25] | ||||

| – | 61 cm | 1852–1857[26] | Chance Brothers | Craig telescope | |||

| Dearborn Observatory | 47 cm | 1862 | Alvan Clark & Sons | Smaller than Craig | |||

| – | 53 cm | 1862 | Buckingham London Exhibition telescope[27] | ||||

| Newall Observatory | 64 cm | 1871 | Chance Brothers | Hardly used until 1891[28] | |||

| U.S. Naval Observatory | 66 cm | 1873 | Alvan Clark & Sons | ||||

| Vienna Observatory | 69 cm | 1880 | Grubb | ||||

| Pulkovo observatory | 76 cm | 1885 | Alvan Clark & Sons | ||||

| Nice Observatory | 77 cm | 1886 | Gautier & Henry | Grande Lunette[20] | |||

| Lick Observatory | 91 cm | 1888 | Alvan Clark & Sons | ||||

| Yerkes Observatory | 102 cm | 1897 | Alvan Clark & Sons | ||||

| – | 125 cm | 1900 | Gautier & Mantois | Paris Exhibition telescope; Used 1 Year Only | |||

Some of the 2nd largest refractors, or otherwise notable.

| Other & Double Telescope Great Refractors | |||||||

| Observatory | Name | Aperture(s) | Year | Lens Maker | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berlin Observatory | 24 cm | 1835 | Merz and Mahler | ||||

| Harvard College Observatory | 38 cm | 1847 | Merz and Mahler[25] | ||||

| Cambridge Observatory | Northumberland Equatorial | 30 cm | 1835 | Cauchoix[29][29] | |||

| Royal Greenwich Observatory | 28-inch Grubb Refractor | 71 cm | 1894 | Chance Brothers[30] | |||

| Astrophysical Observatory Potsdam | Potsdam Große Refraktor | 80 cm + 50 cm | 1899 | ||||

| Paris Observatory | Meudon 33-inch | 83 cm + 62 cm | 1891 | ||||

Focal length

Approximate historical progression in the late 19th century:

| Selected Longest 19th Century Great Refractors after 1873 | |||||||

| Observatory | Length | Aperture | Year(s) | Note | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| U.S. Naval Observatory | 9.9 m | 66 cm (26") | 1873 | ||||

| Vienna Observatory | 10.5 m | 69 cm (27" ) | 1880 | [31] | |||

| Nice Observatory | 17.9 m | 77 cm (30.3")[20] | 1886 | Biscoffscheim | |||

| Treptow Observatory | 21 m | 68 cm (26.77") | 1896 | No dome | |||

| – | 57 m | 125 cm (49.2") | 1900 | Great Paris Exhibition Telescope of 1900 | |||

As long as these were, they were actually much shorter than the longest singlet refractors in aerial telescopes.[32]

Gallery

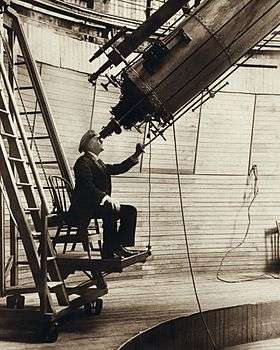

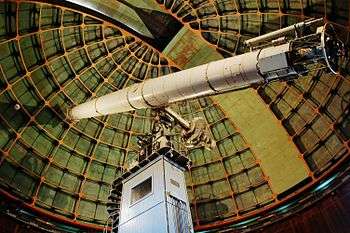

James Lick telescope of 1888, with 91 cm aperture

James Lick telescope of 1888, with 91 cm aperture Four astronomical instruments of the Strasbourg Observatory, including its Großer Refraktor

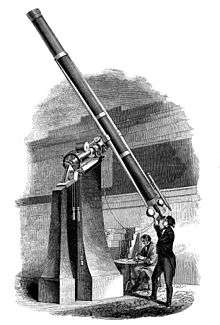

Four astronomical instruments of the Strasbourg Observatory, including its Großer Refraktor Cincinnati Observatory, Illustration of the 11 inch "Merz and Mahler" refracting telescope (from "Smith's Illustrated Astronomy" 1848).

Cincinnati Observatory, Illustration of the 11 inch "Merz and Mahler" refracting telescope (from "Smith's Illustrated Astronomy" 1848).

See also

- Achromatic lens

- Aerial telescope

- Apochromat

- Extremely large telescope

- List of largest optical refracting telescopes

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 18th century

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 19th century

- List of largest optical telescopes in the 20th century

- List of telescope types

References

- ↑ Archived July 16, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "Era: Great Refractors". Amazing-space.stsci.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ "Harvard College Observatory: Great Refractor". Cfa.harvard.edu. 2012-11-21. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ The Massachusetts Teacher. 1848. p. 367.

- ↑ Pettit, Edison (1956). "1956ASPL 7..249P Page 253". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. Articles.adsabs.harvard.edu. 7: 249. Bibcode:1956ASPL....7..249P.

- ↑ "History – British History in depth: The Airy Transit Circle". BBC. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- 1 2 3 "the lens". The Craig Telescope. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ adsabs link Fraunhofer and the Great Dorpat Refractor, Waaland, J. Robert, American Journal of Physics, Volume 35, Issue 4, pp. 344–350 (1967)

- ↑ "Fraunhoferi refraktor". Obs.ee. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ A.H. Batten (1988). Resolute and Undertaking Characters: The Lives of Wilhelm and Otto Struve. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 45. ISBN 978-90-277-2652-0.

- ↑ The great nineteenth century refractors by James Lequeux, Page 1

- ↑ John Woodruff (2003). Firefly Astronomy Dictionary. Firefly Books. p. 71. ISBN 978-1-55297-837-5.

- ↑ Brian Daugherty. "Berlin – History of Astronomy in Berlin". Bdaugherty.tripod.com. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ "Telescope: Yerkes 40-inch Refractor". Amazing-space.stsci.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- 1 2 Misch, Tony; Remington Stone (1998). "The Building of Lick Observatory". Lick Observatory. Univ. of California. Retrieved 2008-06-30.

- 1 2 3 Edgar Sanderson; John Porter Lamberton; Charles Morris (1910). Six Thousand Years of History: Achievements of the nineteenth century. T. Nolan. p. 286.

- ↑ Physics Demystified By Stan Gibilisco, ISBN 0-07-138201-1, page 515 Since a lens can only be held in place by its edge, the center of a large lens will sag due to gravity, distorting the image it produces. The largest practical lens size in a refracting telescope is around 1 meter,

- ↑ Pettit, Edison (1956). "1956ASPL 7..249P Page 255". Astronomical Society of the Pacific Leaflets. Articles.adsabs.harvard.edu. 7: 249. Bibcode:1956ASPL....7..249P.

- ↑ Reed Business Information (1982). New Scientist. Reed Business Information. p. 573.

- 1 2 3 4 "1914Obs 37..245H Page 248". Articles.adsabs.harvard.edu. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ "The Refracting Telescopes of the 19th Century"

- ↑ "BARDOU : Established in Paris in 1818 by D.F. Bardou, then run by his son P.G. Bardou, and grandson, Albert D. Bardou". Europa.com. Retrieved 2014-02-28.

- ↑ Dictionary of National Biography, 1885–1900, Volume 53, "South, James", by Agnes Mary Clerke (WikiSource 2010)

- ↑ Fred Watson (2006). Stargazer: The Life and Times of the Telescope. Perseus Books Group. p. 200. ISBN 978-0-306-81483-9.

- 1 2 http://science.jrank.org/pages/49339/observatory.html. Retrieved August 19, 2010. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ "Welcome to the Online Museum of the Craig Telescope". Craig-telescope.co.uk. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ "How it was constructed". The Craig Telescope. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ Archived March 16, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 Archived March 25, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "The 28-inch photo-visual refractor : : RMG". Nmm.ac.uk. 1944-07-15. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- ↑ The Observatory. Editors of the Observatory. 1881. p. 192.

- ↑ Peter L. Manly (1995). Unusual Telescopes. Cambridge University Press. p. 181. ISBN 978-0-521-48393-3.

Further reading

- "The History of the Development of the Telescope", Authors: Schirach, W. F. H.

- "The Great 19th Century Refractors"

- Hiram Mattison (1856). A High-school Astronomy: In which the Descriptive, Physical, and Practical are Combined : with Special Reference to the Wants of Academies and Seminaries of Learning. F.J. Huntington and Mason Brothers.