Great-circle distance

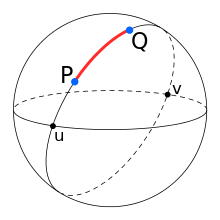

The great-circle distance or orthodromic distance is the shortest distance between two points on the surface of a sphere, measured along the surface of the sphere (as opposed to a straight line through the sphere's interior). The distance between two points in Euclidean space is the length of a straight line between them, but on the sphere there are no straight lines. In spaces with curvature, straight lines are replaced by geodesics. Geodesics on the sphere are circles on the sphere whose centers coincide with the center of the sphere, and are called great circles.

The determination of the great-circle distance is part of the more general problem of great-circle navigation, which also computes the azimuths at the end points and intermediate way-points.

Through any two points on a sphere that are not directly opposite each other, there is a unique great circle. The two points separate the great circle into two arcs. The length of the shorter arc is the great-circle distance between the points. A great circle endowed with such a distance is called a Riemannian circle in Riemannian geometry.

Between two points that are directly opposite each other, called antipodal points, there are infinitely many great circles, and all great circle arcs between antipodal points have a length of half the circumference of the circle, or , where r is the radius of the sphere.

The Earth is nearly spherical (see Earth radius), so great-circle distance formulas give the distance between points on the surface of the Earth correct to within about 0.5%.[1] (See Arc length § Arcs of great circles on the Earth.)

Formulas

Let and be the geographical latitude and longitude in radians of two points 1 and 2, and be their absolute differences; then , the central angle between them, is given by the spherical law of cosines if one of the poles is used as an auxiliary third point on the sphere:[2]

The problem is normally expressed in terms of finding the central angle . Given this angle in radians, the actual arc length d on a sphere of radius r can be trivially computed as

Computational formulas

On computer systems with low floating-point precision, the spherical law of cosines formula can have large rounding errors if the distance is small (if the two points are a kilometer apart on the surface of the Earth, the cosine of the central angle comes out 0.99999999). For modern 64-bit floating-point numbers, the spherical law of cosines formula, given above, does not have serious rounding errors for distances larger than a few meters on the surface of the Earth.[3] The haversine formula is numerically better-conditioned for small distances:[4]

Historically, the use of this formula was simplified by the availability of tables for the haversine function: hav(θ) = sin2(θ/2).

Although this formula is accurate for most distances on a sphere, it too suffers from rounding errors for the special (and somewhat unusual) case of antipodal points (on opposite ends of the sphere). A formula that is accurate for all distances is the following special case of the Vincenty formula for an ellipsoid with equal major and minor axes:[5]

When programming a computer, one should use the atan2() function rather than the ordinary arctangent function (atan()), to place the solution in the correct quadrant when

(90°). Alternatively, if atan() returns a negative answer, add

radians (180°) to it. (This will not, however, work for exactly antipodal points.)

McCaw[6] and Kahan[7] also give formulas for the distance which are accurate for all angles.

Vector version

Another representation of similar formulas, but using normal vectors instead of latitude/longitude to describe the positions, is found by means of 3D vector algebra, i.e. utilizing the dot product, cross product, or a combination:[8]

where and are the normals to the ellipsoid at the two positions 1 and 2. Similarly to the equations above based on latitude and longitude, the expression based on arctan is the only one that is well-conditioned for all angles. The expression based on arctan requires the magnitude of the cross product over the dot product.

From chord length

A line through three-dimensional space between points of interest on a spherical Earth is the chord of the great circle between the points. The central angle between the two points can be determined from the chord length. The great circle distance is proportional to the central angle.

The great circle chord length, , may be calculated as follows for the corresponding unit sphere, by means of Cartesian subtraction:

The central angle is:

Radius for spherical Earth

The shape of the Earth closely resembles a flattened sphere (a spheroid) with equatorial radius of 6378.137 km; distance from the center of the spheroid to each pole is 6356.752 km. When calculating the length of a short north-south line at the equator, the circle that best approximates that line has a radius of (which equals the meridian's semi-latus rectum), or 6335.439 km, while the spheroid at the poles is best approximated by a sphere of radius , or 6399.594 km, a 1% difference. So long as a spherical Earth is assumed, any single formula for distance on the Earth is only guaranteed correct within 0.5% (though better accuracy is possible if the formula is only intended to apply to a limited area). A good choice[6] for the radius is the mean earth radius, (for the WGS84 ellipsoid); in the limit of small flattening, this choice minimizes the mean square relative error in the estimates for distance.

See also

References and notes

- ↑ Admiralty Manual of Navigation, Volume 1, The Stationery Office, 1987, p. 10, ISBN 9780117728806,

The errors introduced by assuming a spherical Earth based on the international nautical mile are not more than 0.5% for latitude, 0.2% for longitude.

- ↑ Kells, Lyman M.; Kern, Willis F.; Bland, James R. (1940). Plane And Spherical Trigonometry. McGraw Hill Book Company, Inc. pp. 323–326. Retrieved July 13, 2018.

- ↑ "Calculate distance, bearing and more between Latitude/Longitude points". Retrieved 10 Aug 2013.

- ↑ Sinnott, Roger W. (August 1984). "Virtues of the Haversine". Sky and Telescope. 68 (2): 159.

- ↑ Vincenty, Thaddeus (1975-04-01). "Direct and Inverse Solutions of Geodesics on the Ellipsoid with Application of Nested Equations" (PDF). Survey Review. Kingston Road, Tolworth, Surrey: Directorate of Overseas Surveys. 23 (176): 88–93. doi:10.1179/sre.1975.23.176.88. Retrieved 2008-07-21.

- 1 2 McCaw, G. T. (1932). "Long lines on the Earth". Empire Survey Review. 1 (6): 259&ndash, 263. doi:10.1179/sre.1932.1.6.259.

- ↑ Kahan, William (September 2004). "Angle subtended at the eye by neighboring stars" (PDF).

- ↑ Gade, Kenneth (2010). "A non-singular horizontal position representation" (PDF). The Journal of Navigation. Cambridge University Press. 63 (3): 395–417. doi:10.1017/S0373463309990415.