Greaser (subculture)

Greasers are a youth subculture that was popularized in the late 1940s and 1950s to 1960s by predominately working class and lower class teenagers and young adults in the United States. The subculture remained prominent into the mid-1960s and was particularly embraced by certain ethnic groups in urban areas, particularly Italian-Americans and Hispanic-Americans, though rural and suburban youth also participated in the subculture to a lesser extent. Rock and roll music, rockabilly and doo-wop were major parts of the culture.

History

Etymology of the term "greaser"

The word "greaser" originated in the 19th century in the United States as a derogatory label for poor laborers, specifically those of Mexican or Italian descent.[1][lower-alpha 1] The term was later used to refer to mechanics. It was not used in writing to refer to the American subculture of the mid-20th century until the mid-1960s, though in this sense it still evoked a pejorative connotation and a relation to machine work.[1][lower-alpha 2] The name was applied to members of the subculture because of their characteristic greased-back hair.[6]

Origins of the subculture and rise to popularity

The greaser subculture may have emerged in the post-World War II era among the motorcycle clubs and gangs of the late 1940s, though it was certainly established by the 1950s.[1][lower-alpha 3] The original greasers were aligned by a feeling of disillusion with American popular culture, either through a lack of economic opportunity in spite of the post-war boom or a marginalization enacted by the general domestic shift towards homogeneity.[7] Most were male, often ethnic and working-class, and held interest in hotrod culture or motorcycling.[1] A handful of middle class youth were drawn to the subculture for its rebellious attitude.[8]

The weak structural foundation of the greasers can be attributed to the subculture's origins in working-class youth with few economic resources with which they could participate in American consumerism.[9] Greasers, unlike motorcyclists, did not explicitly have their own interest clubs or publications. As such, there was no business marketing geared specifically towards the group.[10] Their choice in clothing was largely drawn from a common understanding of the empowering aesthetic of working-class attire, rather than cohesive association with similarly-dressed individuals.[10] Some greasers were in motorcycle clubs or in gangs (and some gang members and bikers dressed like greasers)[10] though such membership was not an inherent principle of the subculture.[1]

Ethnically, original greasers were mostly composed of Italian Americans in the Northeastern United States and Chicanos in the Southwest. Since both of these peoples were mostly olive-skinned, the "greaser" label assumed a quasi-racial status that implied an urban lower class masculinity and delinquency. This development led to an ambiguity in the racial distinction between poor Italian Americans and Puerto Ricans in New York City in the 1950s and 1960s.[9] Greasers were also perceived as being predisposed to perpetrating sexual violence, stoking fear among middle class males and arousal among middle class females.[11]

Decline and modern incarnations

Though the television show American Bandstand helped to "sanitize" the negative image of greasers in the 1960s, sexual promiscuity was still seen as a key component of the modern character.[12] By the mid-1970s, the greaser image had become a quintessential part of 1950s nostalgia and cultural revival.[13]

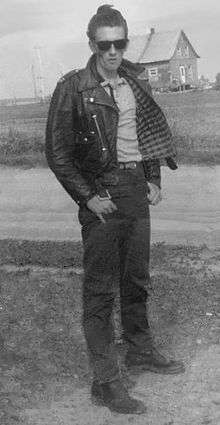

Fashion, style, and culture

The most notable physical characteristic of greasers were their greased hair styles through the use of products such as pomade or petroleum jelly. For males, it was used to fashion coiffures such as the Folsom, Pompadour, Elephant's trunk, or Duck's ass. This was probably adopted from early rock 'n' roll and rockabilly performers such as Elvis Presley. Since the hair products weren't sticky and remained wet the hair had to be frequently reshaped via combing so the style could be maintained.[5] For females, backcombing or teasing the hair was common.[14]

Male greasers typically wore loose cotton twill trousers (common among the working class) or dark blue Levi's jeans (widely popular among all American youth in the 1950s). The latter were often cuffed over ankle-high black or brown leather boots,[5] including cowboy, steel-toed engineer, or harness styles. Other footwear choices included Chuck Taylor All-Stars and brothel creepers.[15] Male tops were typically solid black or white T-shirts, ringer T-shirts, or sometimes tank tops (which would have been retailed as underwear). Outerwear were either denim or leather jackets (including but not limited to Perfecto motorcycle jackets). Female greaser dress included leather jackets and risque clothing such as tight and cropped pants like capris and pedal pushers (broadly popular during the time period).[16]

Music tastes

In the early 1950s there was significant greaser interest in doo-wop, a black genre of music from the industrial cities of the Northeast that had disseminated to mainstream American music through Italian American performers.[9] Greasers were also heavily associated with the culture surrounding rock n' roll, a musical genre which had induced feelings of a moral panic among older, middle class generations during the mid to late 1950s. To many of them, greasers epitomized the connection between rock music and juvenile delinquency professed by several important social and cultural observers at the time.[11]

Portrayal in media and popular culture

The first cinematic representation of the greaser subculture was the 1953 film The Wild One.[17]

Greasers are central characters in the 1957 musical West Side Story and its 1961 film adaptation, the 1967 novel The Outsiders and its 1983 film adaptation, the 1974 film The Lords of Flatbush, and the 1979 film The Wanderers. The phenomenon was given a more farcical treatment in the 1971 stage musical Grease (along with its 1978 film adaptation), which drew its name from the subculture and was based on real-life Chicago Polish greasers in the late 1950s.[18]

The band Sha-Na-Na models their on-stage presence on New York City greasers (the band members themselves were mostly Ivy Leaguers).[19]

See also

Notes

- ↑ The similar term “greaseball” became a slur for individuals of Italian descent, though to a lesser extent it has also been used more generally to refer to all Mediterranean, Latin, or Hispanic people.[2][3][4]

- ↑ S. E. Hinton, author of the novel The Outsiders, an influential portrayal of greasers, knew the term from her youth in the 1950s.[5]

- ↑ Moore writes that there is ambiguity surrounding the birth of the defining greaser fashion and style, though the associated look is similar to the one displayed by post-war bikers.[1]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Moore 2017, p. 138.

- ↑ Dalzell, Tom; Victor, Terry (2015). The New Partridge Dictionary of Slang and Unconventional English. Routledge. p. 1044. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ↑ Aman, Reinhold (1984). Maledicta, Volume 7. Maledicta. p. 29.

- ↑ Ruberto, Laura E.; Sciorra, Joseph (2017). New Italian Migrations to the United States: Vol. 1: Politics and History since 1945. University of Illinois Press.

- 1 2 3 Moore 2017, p. 139.

- ↑ Torres 2017.

- ↑ Moore 2017, pp. 138–139.

- ↑ Symmons 2016, p. 182.

- 1 2 3 Cinotto 2014, Anticipating an Italian American Consumption Culture.

- 1 2 3 Moore 2017, p. 141.

- 1 2 Symmons 2016, pp. 181–182.

- ↑ Cinotto 2014, Footnote #56.

- ↑ Symmons 2016, p. 184.

- ↑ Moore 2017, p. 140.

- ↑ Blanco F. 2015, p. 137.

- ↑ Moore 2017, pp. 139–140.

- ↑ Gelder & Thornton 1997, p. 185.

- ↑ "Bring back our own, original R-rated 'Grease'". 8 January 2009. Archived from the original on 17 November 2013. Retrieved 28 June 2015.

- ↑ "Danny McBride: Guitarist with rock'n' roll revivalists Sha Na Na". The Independent. April 10, 2010.

References

- Blanco F., José (23 November 2015). Clothing and Fashion: American Fashion from Head to Toe (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781610693103.

- Cinotto, Simone, ed. (2014). "10. Consuming Italian Americans: Invoking Ethnicity in the Buying and Selling of Guido". Making Italian America: Consumer Culture and the Production of Ethnic Identities. Fordham University Press. ISBN 9780823256266.

- Gelder, Ken; Thornton, Sarah, eds. (1997). The Subcultures Reader (illustrated, reprint ed.). Psychology Press. ISBN 9780415127271.

- Moore, Jennifer Grayer (2017). Street Style in America: An Exploration (illustrated ed.). ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781440844621.

- Symmons, Tom (2016). The New Hollywood Historical Film: 1967-78 (illustrated ed.). Springer. ISBN 9781137529305.

- Torres, Lucia (January 12, 2017). "Pachucos and Teddy Boys: How Generations of Youth in the U.S. and U.K. Borrowed From Each Other". KCETLink. Retrieved August 7, 2017.