Gorgonopsia

| Gorgonopsians | |

|---|---|

| |

| Skeleton of Sauroctonus parringtoni | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Order: | Therapsida |

| Suborder: | †Gorgonopsia Seeley, 1895 |

| Family: | †Gorgonopsidae Lydekker, 1890 |

| Genera | |

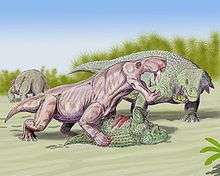

Gorgonopsia ("Gorgon face") is an extinct suborder of theriodonts. Like other therapsids, gorgonopsians (or gorgonopsids) were at one time called "mammal-like reptiles", although this is not accurate.

Description

Their mammalian specializations include differentiated (heterodont) tooth shape, a fully developed temporal fenestra, pillar-like rear legs, a vaulted palate that may have facilitated breathing while holding the prey, and incipiently developed ear bones.[1] Gorgonopsians are a part of a group of therapsids called theriodonts, which includes mammals.[2] They were among the largest carnivores of the late Permian. The largest known, Inostrancevia, was the size of a large bear with a 45-centimetre-long (18 in) skull, and 12-centimetre-long (4.7 in) sabre-like teeth (clearly an adaptation to being a carnivore). Some mammals, like Smilodon would also have sabre-like teeth. They are traditionally thought to not have had a full pelage,[3] but some Late Permian coprolites showcasing remnants of fur may belong to them;[4] whether they had bristles or scales is unknown. They possibly had a combination of all of these, as some mammals still do. Like most therapsids, they are assumed to have been terrestrial, and this is supported both by their morphology and bone microanatomy.[5]

Evolutionary history

Gorgonopsians are theriodonts, a major group of therapsids that included the ancestors of mammals. They evolved in the Middle Permian, from a reptile-like therapsid that also lived in that period. The early gorgonopsians were small, being no larger than a dog. The extinction of dinocephalians (which dominated the Middle Permian world) led to gorgonopsids becoming the apex predators of the Late Permian. Some had approached the size of a rhinoceros, such as Inostrancevia, the largest gorgonopsian. A nearly complete fossil of Rubidgea has been found in South Africa.[6] The Gorgonopsia became extinct at the end of the Permian period, being the only theriodont line to be terminated by this mass extinction.

Classification

The gorgonopsians are one of the three groups of theriodonts (the other two were the therocephalians, and the cynodonts). Theriodonts are related to the herbivorous Anomodontia. Gorgonopsia includes three subfamilies, the Gorgonopsinae, Rubidgeinae and Inostranceviinae, plus a larger number of genera that have not been placed in any of these groups. In all, there are 25 genera and 41 species, with the genera described most completely being Dinogorgon, Inostrancevia and Rubidgea.

Gorgonopsian taxonomy is poorly understood. Many species of gorgonopsian were named by Robert Broom, a notorious splitter, many of whose taxa are now regarded as invalid.[7] Many species distinctions among gorgonopsians have been based on minor differences which can be easily affected by preservation.[8]:3 As a result of these difficulties, relatively little research has gone into resolving gorgonopsian taxonomy and phylogeny.[8]:1–2

The most comprehensive review of the group is by Sigogneau-Russell, 1989.[9] However, many gorgonopsian taxa have had their taxonomy changed since then.[8]

- Order Therapsida

- SUBORDER GORGONOPSIA

- Family Gorgonopsidae

- Aelurosaurus

- Aloposaurus

- Arctognathus

- Arctops

- Broomisaurus

- Cerdorhinus

- Cyonosaurus

- Eriphostoma

- Kamagorgon

- Lycaenops

- "Njalila"

- Nochnitsa

- Paragalerhinus

- Smilesaurus

- Suchogorgon

- Viatkogorgon

- "Gorgonops" dixeyi

- Subfamily Gorgonopsinae

- Subfamily Inostranceviinae

- Subfamily Rubidgeinae

- Family Gorgonopsidae

Gebauer (2007) conducted a phylogenetic analysis of gorgonopsians. She did not consider Gorgonopsia and Gorgonopsidae to be equivalent, and placed only species with autapomorphies, or characteristics unique to those species, in Gorgonopsidae; accordingly, Aloposaurus, Cyonosaurus, and Aelurosaurus were placed outside Gorgonopsidae as basal gorgonopsids. Below is a cladogram resulting from her analysis:[10]

| Gorgonopsia |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

The most comprehensive published phylogeny of gorgonopsians to date was conducted by Christian Kammerer and Vladimir Masyutin in their study of the Russian genera Nochnitsa and Viatkogorgon. Unlike previous phylogenies, it found African gorgonopsians to form a clade to the exclusion of all other gorgonopsians.[11]

| Gorgonopsia |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

The habitual head posture was anteriorly tilted revealed by the orientation of the horizontal semicircular canal.[12] They possessed relatively large floccular fossa, a portion of the cerebellum that controls gaze stability.[12]

Gorgonopsians were likely active predators, based on their powerful senses of smell and their fairly good eyesight. Gorgonopsians were also seemingly plantigrade walkers, based on their skeletal morphology, and probably possessed a gait similar to a "crocodilian high-walk". This posture would have permitted them to be much faster than many of their potential prey species, such as dicynodonts and pareiasaurs, particularly in conjunction with their reduced, almost mammalian phalangeal formula and more symmetrical feet. Their hunting strategy was probably one of ambush; lying in wait before lunging at speed to grapple prey with their front limbs and attack their prey with their saber-teeth. Unlike later sabertooths such as the machairodontines, gorgonopsians likely were less precise in regards to bite placement; as they had reptilian jaws and tooth arrangements, gorgonopsians probably hunted by using a bite-and-retreat technique to weaken and debilitate their victim before moving in to attack the throat, underbelly and other vulnerable areas. Due to the fact that most gorgonopsians lack any post-canine cutting teeth, meat would have been torn away from a carcass using the powerful jaw muscles and incisors before being gulped down and swallowed whole.[13]:204–207

During most of the late Permian, gorgonopsians were the apex predators of their ecosystems. However, earlier in their evolutionary history, during the middle Permian, gorgonopsians such as the recently discovered Nochnitsa were fairly small, rare animals.[11] The discovery of Nochnitsa in conjunction with the larger therocephalian Gorynychus indicates that after the extinction of dinocephalians but before gorgonopsians rose to dominance, basal therocephalians were the apex predators of Permian ecosystems.[14][15]

Some gorgonopsians, such as the small, basal gorgonopsian Viatkogorgon, were nocturnal.[11] Others, such as the large rubidgeine Clelandina, were diurnal.[8]

See also

| Wikispecies has information related to Gorgonopsia |

References

- ↑ Laurin, Michel (1998). "New data on the cranial anatomy of Lycaenops (Synapsida, Gorgonopsidae), and reflections on the possible presence of streptostyly in gorgonopsians". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 18 (4): 765–776. doi:10.1080/02724634.1998.10011105. JSTOR 4523954.

- ↑ Amson, Eli; Laurin, Michel (2011). "On the affinities of Tetraceratops insignis, an Early Permian synapsid". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 56 (2): 301–312. doi:10.4202/app.2010.0063.

- ↑ Ruben, John A.; Jones, Terry D. (2000). "Selective Factors Associated with the Origin of Fur and Feathers". American Zoologist. 40 (4): 585–596. doi:10.1093/icb/40.4.585.

- ↑ Bajdek, Piotr; Qvarnström, Martin; Sulej, Tomasz; Sennikov, Andrey G.; Golubev, Valeriy K.; Niedźwiedzki, Grzegorz (2015). "Microbiota and food residues including possible evidence of pre‐mammalian hair in Upper Permian coprolites from Russia". Lethaia. 49 (4). doi:10.1111/let.12156.

- ↑ Kriloff, A.; Germain, D.; Canoville, A.; Vincent, P.; Sache, M.; Laurin, M. (2008). "Evolution of bone microanatomy of the tetrapod tibia and its use in palaeobiological inference". Journal of Evolutionary Biology. 21 (3): 807–826. doi:10.1111/j.1420-9101.2008.01512.x. PMID 18312321.

- ↑ University of Washington (10 December 1998). "First Complete Fossil Of Fierce Prehistoric Predator Found In South Africa". ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Wyllie, Alistair (2003). "A review of Robert Broom's therapsid holotypes: have they survived the test of time?". Palaeontologia Africana. 39: 1–19. hdl:10539/15952.

- 1 2 3 4 Kammerer, Christian F. (2016). "Systematics of the Rubidgeinae (Therapsida: Gorgonopsia)". PeerJ. 4. doi:10.7717/peerj.1608. PMC 4730894.

- ↑ Sigogneau-Russell, Denise (1989). Wellnhofer, Peter, ed. Theriodontia I: Phthinosuchia, Biarmosuchia, Eotitanosuchia, Gorgonopsia. Encyclopedia of Paleoherpetology. 17 B/I. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag. ISBN 3437304879.

- ↑ Gebauer, Eva V. I. (2007). Phylogeny and Evolution of the Gorgonopsia with a Special Reference to the Skull and Skeleton of GPIT/RE/7113 ('Aelurognathus?' parringtoni) (PhD thesis). Tübingen: Eberhard-Karls Universität Tübingen. hdl:10900/49062.

- 1 2 3 Kammerer, Christian F.; Masyutin, Vladimir (2018). "Gorgonopsian therapsids (Nochnitsa gen. nov. and Viatkogorgon) from the Permian Kotelnich locality of Russia". PeerJ. 6. doi:10.7717/peerj.4954. PMC 5995105.

- 1 2 Araújo, Ricardo; Fernandez, Vincent; Polcyn, Michael J.; Fröbisch, Jörg; Martins, Rui M. S. (2017). "Aspects of gorgonopsian paleobiology and evolution: insights from the basicranium, occiput, osseous labyrinth, vasculature, and neuroanatomy". PeerJ. 5. doi:10.7717/peerj.3119. PMC 5390774.

- ↑ Antón, Mauricio (2013). Sabertooth. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press. ISBN 9780253010421.

- ↑ North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences (8 June 2018). "'Monstrous' new Russian saber-tooth fossils clarify early evolution of mammal lineage". ScienceDaily.

- ↑ Kammerer, Christian F.; Masyutin, Vladimir (2018). "A new therocephalian (Gorynychus masyutinae gen. et sp. nov.) from the Permian Kotelnich locality, Kirov Region, Russia". PeerJ. 6. doi:10.7717/peerj.4933. PMC 5995100.

Further reading

- Bakker, R.T. (1986), The Dinosaur Heresies, Kensington Publishing Corp.

- Cox, B. and Savage, R.J.G. and Gardiner, B. and Harrison, C. and Palmer, D. (1988) The Marshall illustrated encyclopedia of dinosaurs & prehistoric animals, 2nd Edition, Marshall Publishing.

- Fenton, C.L. and Fenton, M.A. (1958) The Fossil Book, Doubleday Publishing.

- Hore, P.M. (2005), The Dinosaur Age, Issue #18. National Dinosaur Museum.

- Ward, P.D. (2004), Gorgon, Viking Penguin.