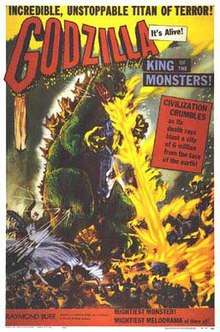

Godzilla, King of the Monsters!

| Godzilla, King of the Monsters! | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by |

Terry Morse Ishirō Honda |

| Produced by |

Tomoyuki Tanaka Uncredited: Richard Kay Harry Rybnick Edward B. Barison[1] |

| Screenplay by |

Takeo Murata Ishirō Honda Uncredited: Al C. Ward |

| Story by | Shigeru Kayama |

| Starring |

Raymond Burr Takeshi Shimura Momoko Kōchi Akira Takarada Akihiko Hirata Haruo Nakajima |

| Music by | Akira Ifukube |

| Cinematography |

Masao Tamai Guy Roe |

| Edited by | Terry Morse |

Production company |

Toho Jewell Enterprises |

| Distributed by |

TransWorld Releasing Corporation (US, West) Embassy Pictures (US, East) Toho (Japan) |

Release date |

May 29, 1957 (Japan) |

Running time | 80 minutes |

| Country |

Japan United States |

| Language |

Japanese English |

| Budget | $650,000 |

| Box office | $2 million (US) |

Godzilla, King of the Monsters! is a 1956 Japanese-American science fiction kaiju film, co-directed by Terry O. Morse and Ishirō Honda. It is a heavily re-edited American adaptation, commonly referred to as an "Americanization",[2][3][4][5][6][7][8] of the 1954 Japanese film Godzilla. In the United States the original black-and-white film had previously been shown subtitled in Japanese community theaters only. Except for Spain and Poland, the film was unknown in Europe. This reedited version introduced all other viewing audiences to the character and labeled Godzilla the "King of the Monsters". In Japan the film was released as Monster King Godzilla (怪獣王ゴジラ Kaiju Ō Gojira).

For this "new" version of Godzilla, some of the original Japanese dialogue was dubbed into English, and some of the political, social, and anti-nuclear themes and overtones were removed completely. This resulted in 16 minutes of footage being cut from the original and being replaced with new footage shot exclusively for Godzilla's North American release. Canadian actor Raymond Burr was cast in the lead role of American journalist Steve Martin, from whose perspective the U.S. version is told, mainly through flashbacks and voice-over narration. The new footage featured Burr interacting with Japanese-American actors and look-alikes in order to make it appear that he was in the original Japanese production.

After World War II, a handful of independent, low-budget films had been made in Japan by American companies that featured Japanese players in the cast. For its U.S. theatrical release, this new version of Godzilla was given A-picture status and bookings, the first feature film to present the Japanese in principal, heroic roles and as sympathetic victims of the destruction of Tokyo (albeit via a fictional giant monster).

It was this version of Godzilla that introduced audiences worldwide to the character and its franchise. It was the only version that critics and scholars had any access to until 2004, when the 1954 original was finally released in select North America theaters.[9]

Plot

American reporter Steve Martin (Raymond Burr) is brought from the ruins of Tokyo to a hospital filled with maimed and wounded citizens. Emiko (Momoko Kochi) finds him among the victims and attempts to find a doctor for him.

Martin recalls in flashback stopping over in Tokyo, where a series of inexplicable ship disasters catches his attention. When a sole survivor washes up on Odo Island, Martin flies there for the story along with Tomo Iwanaga (Frank Iwanaga), a representative of the Japanese Security Defense Forces (JSDF). He learns of the island inhabitants' long-held belief in a sea monster god known to them as "Godzilla", which they believe is causing the disasters. That night, a heavy rain and wind storm strikes the island, destroying many houses and killing some villagers. The locals believe that Godzilla and not the storm are responsible for the destruction.

Martin returns to the island with Dr. Yamane (Takashi Shimura), who leads an investigative crew to Odo Island, where in the ruins, huge radioactive footprints and a trilobite are discovered. An alarm rings and Martin, the villagers, and Dr. Yamane's crew head up a hill for safety. Near the summit, the crew see Godzilla's head and upper torso looking down upon them, and they quickly flee downhill. Dr. Yamane later returns to Tokyo to present his findings: Godzilla was resurrected by repeated nuclear tests in the Pacific. The military responds by attempting to kill the giant creature with depth charges, much to Yamane's dismay. Martin contacts his old friend, Dr. Daisuke Serizawa (Akihiko Hirata), for dinner, but Serizawa declines due to planned commitments with his fiancé.

Emiko, Dr. Yamane's daughter, goes over to Serizawa's home to break off her arranged engagement to him. She is actually in love with Hideo Ogata (Akira Takarada), a salvage ship captain. Dr. Serizawa, however, gives her a demonstration of his secret project, which horrifies her. She is sworn to secrecy and unable to bring herself to break off the engagement. Godzilla surfaces from Tokyo Bay, unharmed by the depth charges, and attacks the city. The next morning, to repel Godzilla, the JSDF arranges for a modification to the tall electrical towers along the Tokyo coast.

The King of the Monsters resurfaces that night and easily breaks through the electrical tower "fences" and JSDF tank defense line by using his atomic heat breath. Using a tape recorder, Martin documents Godzilla's annihilation of the city and is nearly killed during the attack. Godzilla returns to the sea leaving Tokyo a burning, destroyed ruin. Here, the flashback ends, and Martin wakes up in the hospital with Emiko and Ogata. Horrified by the destruction, Emiko reveals to Martin and Ogata the existence of Dr. Serizawa's Oxygen Destroyer, which disintegrates oxygen atoms in salt water and causes all marine organisms to die of acidic asphyxiation. Emiko and Ogata go to Dr. Serizawa to convince him to use the Oxygen Destroyer, but he initially refuses. After watching a television broadcast showing the nation's plight, Dr. Serizawa finally gives in to their pleas.

A Navy ship takes Ogata and Serizawa out to the deepest part of Tokyo Bay to plant the underwater weapon near Godzilla. Wearing deep sea diving gear, Ogata and Dr. Serizawa are lowered by lifelines down to the bottom. After they move into position, Ogata signals the surface and is pulled up, but Serizawa delays his ascent and suddenly activates the device. He radios the surface to tell them that it is working, after which he removes his knife and cuts his diving helmet's oxygen supply line, taking the secret of his Oxygen Destroyer to the grave. The mission succeeds in obliterating Godzilla. Aboard ship, all mourn the unexpected loss of Dr. Serizawa. In this solemn moment, Martin makes a final observation: "The menace was gone...so was a great man. But the whole world could wake up and live again".

Cast

- Raymond Burr as Steve Martin

- Takashi Shimura as Dr. Yamane

- Momoko Kōchi as Emiko

- Akira Takarada as Ogata

- Akihiko Hirata as Dr. Serizawa

- Sachio Sakai as Hagiwara

- Fuyuki Murakami as Dr. Tabata

- Ren Yamamoto as Seiji

- Toyoaki Suzuki as Shinkichi

- Tadashi Okabe as Dr. Tabata's Assistant

- Toranosuke Ogawa as President of Company

- Frank Iwanaga as Security Officer Tomo

- James Hong as Ogata and Dr. Serizawa (English voices)[10]

- Sammee Tong as Dr. Yamane (English voice)[10]

- Haruo Nakajima as Godzilla[11]

- Katsumi Tezuka as Godzilla[11]

Production

In 1955, Edmund Goldman "discovered" the original Japanese-language Godzilla screening at a cinema in Los Angeles. He bought the international rights for $25,000, then sold them to Jewell Enterprises Inc., a small production company owned by Richard Kay and Harold Ross which, with backing from Terry Turner and Joseph E. Levine, successfully adapted it for American audiences. Levine paid $100,000 for his share.[12]

The adaptation process consisted of filming numerous new scenes featuring Raymond Burr and others, and inserting them into an edited version of the Japanese original to create a new film. The new scenes, written by Al C. Ward and directed by Terry O. Morse, were photographed by Guy Roe, with careful attention being paid to matching the visual tone of the Japanese film. Burr's character, Steve Martin, appears to interact with the original Japanese cast. This is accomplished through intricate cutting and the use of body doubles for the Japanese principals, in matching dress, shot from behind, while in direct interaction with Burr's character.

A documentary style was imposed on the original dramatic material through Burr's dialogue and stentorian narration; he plays an American reporter, replacing a comical reporter character in the Japanese original. This turned out to be quite easy to do, as Ishiro Honda's original story had already been told in a semi-documentary form.

More importantly, Burr's presence as the lead character served to ease American audiences into comfortable relationships with characters, whose mere nationality might otherwise have made them difficult to relate to. For similar reasons, protracted dialogue regarding the arranged marriage between the Japanese heroine and a scientist was greatly reduced, as the concept would have been unfamiliar to a 1950s American audience. Scenes evincing an active affair between the two characters were also cut to avoid offending the parents of the film's youthful target audience.

A raging debate in Japan's Diet over the U.S. atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and continued nuclear testing was considered unlikely to be approved of by American veterans of the recent world war, and the theme of devastation of Japan by nuclear holocaust became sublimated in the editing. This theme was not entirely eliminated, however, giving the film a subversiveness on the nuclear question that would later be consciously recognized by the youngsters, at whom the film was aimed, as they entered adulthood. The producers were still able to keep at least a hint of the "nuclear" connotation, since atomic-mutation monster movies were becoming popular in the U.S. at that time (Them!, Tarantula, The Amazing Colossal Man, etc.). While Ishiro Honda's original film had a very serious, anti-nuclear tone, this seemed to be overlooked by American audiences that had already become accustomed to watching Hollywood B-movie atomic-related story plot lines.

This production is one of a select few general release American films (including Night of the Living Dead) that were not composed for widescreen viewing, despite being released after the widescreen transition of the early to mid 1950s. The new Guy Roe-shot sequences were composed for Academy ratio, just like the Japanese footage, and the end credits were blocked much too tightly for any amount of matting to be possible without causing lines of text to trail off the screen. Since 80% of downtown theaters and 69% of neighborhood theaters had already converted to widescreen by the end of 1953, and since theaters that made the transition would not have their old Academy ratio aperture plates on hand anymore, it is very likely that many people saw the film in a matted widescreen ratio, such as 1.85:1. This had become the non-anamorphic industry standard by September 1956.[13]

Release

There has been some confusion about who distributed the film to the U.S. The film poster states that it is "A Trans World Release", while it also bears a copyright notice for "Godzilla Releasing Corporation". Trade reviews from its New York theatrical engagement indicate that it was released by Embassy Pictures. Classic Media indicates that the film was released by Jewell Enterprises, but the screen credits only show this company as presenting the film. In fact, the film was adapted from the Japanese original by Jewell Enterprises, which took "presentation" credits on screen and in some of the advertising copy. In this adapted form, Jewell copyrighted the film under Godzilla Releasing Corporation and then nationally released it under control of TransWorld Releasing Corporation. All these companies were owned by Rybnick and Kay. The film was actually distributed in the western U.S. by TransWorld Releasing Corporation and in the eastern U.S. by Joseph E. Levine's Embassy Pictures, which was then only a Boston-based states rights exchange. Embassy was most frequently noted as the sole distributor in reviews and trade annuals published in New York. Godzilla, King of the Monsters was given "A-film" promotion and opened on April 27, 1956 at Loew's State Theatre on Broadway and 45th Street in New York City.

New York Times film critic Bosley Crowther gave the film a bad review the following day. He dismissed it with: "'Godzilla', produced in a Japanese studio, is an incredibly awful film". After complaining about the dubbing, the special effects ("a miniature of a dinosaur") and an alleged similarity to King Kong he concluded, "The whole thing is in the category of cheap cinematic horror-stuff, and it is too bad that a respectable theater has to lure children and gullible grown-ups with such fare".[14]

Crowther notwithstanding, the film was a notable hit with the American public and was a box office success, grossing up to $2 million in the United States alone.[15] It easily exported to Europe and South America, where the original was unknown and where it also had a major impact. The door was thus opened in the Americas and Europe for the import of unexpurgated Japanese science fiction, horror, and other commercial film products; it also garnered western awareness of Toho Studios, which had retained producer credit. In 1957 the film made its way full circle back to Japan, where it was exhibited as Kaiju Ō Gojira (怪獣王ゴジラ, lit. "Monster King Godzilla"), becoming at least as popular as the original, replacing the latter in Japanese theaters and influencing future sequels and remakes.

After its theatrical run, Godzilla, King of the Monsters! became a television staple for decades, even into the cable era, opening up the international market for dozens of Godzilla sequels. In the era before widespread home videos, the film was regularly re-shown in repertory theaters and drive-in theaters. At the film review aggregator website Rotten Tomatoes, the film has an approval rating of 83%, based on 23 reviews, with an average rating of 6.8/10.[16]

In its original theatrical version, the film opened with the TransWorld Releasing Corporation logo. It was merely the Toho logo, with a rotating globe optically printed over it and the text, "A Transworld Release" overlaid in capital letters. Following the fadeout of the final scene, the schoolchildren's hymn being sung was reprised over the cast and credits. "The End" title followed in white lettering on a black background, with Godzilla's echoing footsteps eerily replacing the soulful music. However, when the film went into television syndication in the late 1950s, the credit sequence was removed to make room for more commercial time, leaving only the "The End" title card. In the early 1980s, Henry G. Saperstein acquired the film for TV re-syndication and for videotape and LaserDisc release by Vestron Video; the TransWorld logo was also removed, and all re-issues thereafter were taken from the Vestron-revised master (even the so-called "uncut" DVD version from Simitar released in 1988). This missing material was partially restored in 2006 on the Sony release; however, the TransWorld logo was left off and cast credits were presented in a "squashed" widescreen letterbox format and placed after "The End" card instead of before. In 2012 the Criterion Collection restored the film and reinstated all missing material in the correct order for their high definition Blu-ray/DVD release.

In its original TV syndication, a credit screen reading "Starring Raymond Burr, directed by Terry Morse and I. Honda" in white lettering over a black background, was placed between the main title and the opening shot of Tokyo in ruins. These "opening credits" have never appeared on home video.

Sequel

In 1985, New World Pictures released Godzilla 1985, an American adaptation of Toho's The Return of Godzilla. Like Godzilla, King of the Monsters!, it used footage from the Toho film, with added footage shot in Hollywood, and the dialog re-recorded in English. Raymond Burr would reprise his role as Steve Martin, acting as an adviser to the Pentagon, but did not interact within the main story as he had done in King of the Monsters. Return of Godzilla was a sequel to the original 1954 film, and Godzilla 1985 served as a sequel to Godzilla, King of the Monsters!.

Cozzilla

In 1977 Italian filmmaker Luigi Cozzi released a further modified and colorized version of Godzilla to Italian theaters, with a soundtrack that used a magnetic tape process similar to sensurround. Originally, Cozzi had planned to just re-release the original 1954 Godzilla (without the Raymond Burr footage). He was unable to secure the rights from Toho, so he purchased rights to the Americanized version. Being in black-and-white, however, Italian regional distributors refused to release it. So Cozzi hired Armando Valcauda to colorize the entire film, frame-by-frame, using a process called "Spectrorama 70". The process consisted of applying various colored gels to the footage. This resulted in it becoming one of the first colorized black-and-white films.

This new version was advertised as "The greatest apocalypse in the history of cinema with the sonorous and visual wonder of Spectrorama 70". The film's content was also re-edited, adding new scenes and stock footage of graphic death and destruction (including a famous scene where Godzilla destroys a train),.[17] This increased the film's running time to 105 minutes.

The soundtrack was composed by Vince Tempera, Franco Bixio, and Fabio Frizzi under the "Magnetic System" screen credit. In cinemas the soundtrack was played in "Futursound", an 8-track magnetic tape system based on Sensurround. Special sonic effects vibrated the seats each time that Godzilla took a step. Cozzi's version was a success and received generally positive reviews. It's theatrical release poster was later used as the cover for Fangoria #1.

Most prints of Cozzi's release were lost but some still exist. A bootleg version was released on VHS tape, but the quality is poor when compared to the theatrical release print. The Cozzi version had only been released in Italy by 2012, but it has since been shown in Japan and Turkey.[18] On November 24, 2017, the Cozzi version was screened at the Fantafestival in Rome.[19]

In 2014 a bootleg, subtitled VHS copy was uploaded on YouTube in its semi-entirety, albeit in poor quality.[20] On February 7, 2018, a restored version of the Cozzi's film (by television personality Geno Cuddy) emerged at the Internet Archive.[21]

See also

Note

- ^ This WikiProject Films infobox contains information regarding the Americanized U.S. release; for information on the Japanese original, see Godzilla.

References

- ↑ Galbraith IV 2008, p. 106.

- ↑ Ragone, August; Tucker, Guy (1991). "The Legend of Godzilla: Part 1". Markalite, the Magazine of Japanese Fantasy #3. Pacific Rim Publishing.

- ↑ Ragone, August (November 2007). "Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters". Chronicle Books. pp. 46–47. Archived from the original on 2015-06-20.

- ↑ "Classic Media Reissues the Original Godzilla on DVD". Scifi Japan. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Hanlon, Patrick (May 14, 2014). "Godzilla: What Is It About Monsters?". Forbes.

- ↑ Rafferty, Terrence (May 2, 2004). "The Monster That Morphed Into a Metaphor". NY Times.

- ↑ Roberto, John Rocco (July 1994). "Godzilla in America". G-fan Magazine Issue #10. Archived from the original on 2014-10-06.

- ↑ "Godzilla (1954) - The Criterion Collection". Criterion. Retrieved September 1, 2014.

- ↑ Ryfle & Godziszewski 2017, p. 106.

- 1 2 Ryfle 1998, p. 54.

- 1 2 Ryfle 1998, p. 351.

- ↑ Scheuer, P. K. (1959, Jul 27). Meet joe levine, super(sales)man! Los Angeles Times (1923-Current File). Retrieved from http://search.proquest.com/docview/167430798

- ↑ "Widescreen Documentation". 3dfilmarchive.com. Retrieved June 26, 2014.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (April 28, 1956). "Screen: Horror Import; 'Godzilla' a Japanese Film, Is at State" (PDF, fee required). The New York Times. Retrieved 2008-04-07.

- ↑ Lees & Cerasini 1998, p. 16.

- ↑ "Godzilla, King of the Monsters! (1956)". Rotten Tomatoes. Fandango. Retrieved April 21, 2018.

- ↑ Ryfle 1998, p. 209.

- ↑ "Talking Cozzilla: An Interview with Italian Godzilla Director Luigi Cozzi". scifijapan.com. Retrieved November 10, 2012.

- ↑ Programma 2017 Fantafestival (in Italian)

- ↑ Gibson, Daniel (May 22, 2014). "Cozzilla (1977) full movie". Youtube. Archived from the original on July 8, 2014. Retrieved 10 August 2018.

- ↑ Luigi Cozzi's Godzilla (Cozzilla, 1977) Geno Cuddy Restoration is available for free download at the Internet Archive

Bibliography

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (1994). Japanese Science Fiction, Fantasy, and Horror Films : A Critical Analysis of 103 Features Released in the United States, 1950-1992. McFarland.

- Galbraith IV, Stuart (2008). The Toho Studios Story: A History and Complete Filmography. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0810860049.

- Lees, J.D.; Cerasini, Marc (1998). The Official Godzilla Compendium. Random House. ISBN 0-679-88822-5.

- Ryfle, Steve (1998). Japan's Favorite Mon-Star: The Unauthorized Biography of the Big G. ECW Press. ISBN 1550223488.

- Ragone, August (2014). Eiji Tsuburaya: Master of Monsters (2nd Edition). Chronicle Books. ISBN 978-0-8118-6078-9.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching The Skies, American Science Fiction Movies of the 50s, Vol. I: 1950 - 1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Godzilla, King of the Monsters! |

- Godzilla, King of the Monsters! on IMDb

- Godzilla, King of the Monsters! at AllMovie

- Godzilla, King of the Monsters! at the TCM Movie Database

- Godzilla, King of the Monsters! at the American Film Institute Catalog

- Godzilla, King of the Monsters! at Rotten Tomatoes