Global Hunger Index

The Global Hunger Index (GHI) is tool that measures and tracks hunger globally, by region, and by country.[1][2][3] The GHI is calculated annually, and its results appear in a report issued in October each year.

Created in 2006, the GHI was initially published by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) and Welthungerhilfe. In 2007, the Irish NGO Concern Worldwide also became a co-publisher.[4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14] In 2018, the GHI was a joint project of Welthungerhilfe and Concern Worldwide, with IFPRI stepping aside from its involvement in the report.

The 2018 Global Hunger Index (GHI) report—the 13th in the annual series—presents a multidimensional measure of national, regional, and global hunger by assigning a numerical score based on several aspects of hunger. It then ranks countries by GHI score and compares current scores with past results. The 2018 report shows that in many countries and in terms of the global average, hunger and undernutrition have declined since 2000; in some parts of the world, however, hunger and undernutrition persist or have even worsened. Since 2010, 16 countries have seen no change or an increase in their GHI levels.

Besides presenting GHI scores, each year the GHI report includes an essay addressing one particular aspect of hunger. The 2018 report considers the issue of forced migration and hunger.

In previous years, topics included:

- In 2010: Early childhood undernutrition among children younger than the age of two.[16]

- In 2011: Rising and more volatile food prices of the recent years and the effects these changes have on hunger and malnutrition.[17]

- In 2012: Achieving food security and sustainable use of natural resources, when the natural sources of food become increasingly scarce.[18]

- In 2013: Strengthening community resilience against undernutrition and malnutrition.[19]

- In 2014: Hidden hunger, a form of undernutrition characterized by micronutrient deficiencies.[20]

- In 2015: Armed conflict and its relation to hunger.[21]

- In 2016: Reaching the UN Sustainable Development Goal of zero hunger by 2030.

- In 2017: The challenges of inequality and hunger.

In addition to the yearly GHI, the Hunger Index for the States of India (ISHI) was published in 2008[22] and the Sub-National Hunger Index for Ethiopia was published in 2009.[23]

An interactive map allows users to visualize the data for different years and zoom into specific regions or countries.

Calculation of the Index

The Index ranks countries on a 100-point scale, with 0 being the best score (no hunger) and 100 being the worst, although neither of these extremes is reached in practice. Values from 0 to 9.9 reflect low hunger, values from 10.0 to 19.9 reflect moderate hunger, values from 20.0 to 34.9 indicate serious hunger, values from 35.0 to 49.9 reflect alarming hunger, and values of 50.0 or more reflect extremely alarming hunger levels.[4]

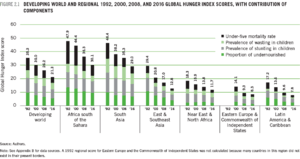

The GHI combines 4 component indicators: 1) the proportion of the undernourished as a percentage of the population; 2) the proportion of children under the age of five suffering from wasting; 3) the proportion of children under the age of five suffering from stunting; 4) the mortality rate of children under the age of five.[GHI2016 1]

The data and projections used for the 2017 GHI are for the period from 2011 to 2016—the most recent available data for the four components of the GHI. The data on the proportion of undernourished come from the Food and Agriculture Organization of the UN (FAO) and include authors' estimates.[5] Data on child wasting and stunting are collected from UNICEF, the World Health Organization, the World Bank, WHO, MEASURE DHS, the Indian Ministry of Women and Child Development, and also include the authors’ own estimates.[GHI2016 2] Data on child mortality are from the UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation.[6]

Global and regional trends

Although the 2017 GHI shows long-term progress in the reduction of hunger worldwide, millions are still experiencing chronic hunger and any places are suffering acute food crises and even famine. The 2017 GHI overall score is 27 percent lower than the 2000 score. Of the 119 countries assessed in this year's report, one falls in the extremely alarming range on the GHI Severity Scale; 7 are in the alarming range; 44 in the serious range; and 24 in the moderate range. Only 43 countries have scores considered low.

The regions of the world struggling most with hunger are South Asia and Africa south of the Sahara, with scores in the serious range (30.9 and 29.4, respectively). The scores of East and Southeast Asia, the Near East and North Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Eastern Europe and the Commonwealth of Independent States range from low to moderate (between 7.8 and 12.8). These averages conceal some troubling results within each region, however, including scores in the serious range for Tajikistan, Guatemala, Haiti, and Iraq, and alarming in the case of Yemen, as well as scores in the serious range for half of all countries in East and Southeast Asia, whose average benefits from China's low score of 7.5.

Because data on the prevalence of undernourishment and, in some cases, data or estimates on child stunting and child wasting were unavailable, 2017 GHI scores could not be calculated for 13 countries. Yet the countries with missing data may be the ones suffering most. Based on the available data and information from international organizations that specialize in hunger and undernutrition, 9 of the 13 countries that lack sufficient data for calculating 2017 GHI scores still raise significant concern—Burundi, Comoros, Democratic Republic of Congo, Eritrea, Libya, Papua New Guinea, Somalia, South Sudan, and Syria.

Ranking

| Global Hunger Index[7] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2018[8] |

| 68 | 44.4 | 36.4 | 25.9 | 20.1 | |

| 69 | 25.9 | 21.6 | 20.6 | 20.2 | |

| 70 | 27.5 | 23.8 | 22.0 | 20.8 | |

| 71 | 41.2 | 33.7 | 26.1 | 21.1 | |

| 72 | 36.8 | 31.4 | 24.5 | 21.2 | |

| 73 | 25.5 | 26.5 | 24.5 | 21.9 | |

| 74 | 26.5 | 24.9 | 24.4 | 22.1 | |

| 75 | 27.3 | 26.2 | 22.3 | 22.3 | |

| 76 | 28.9 | 27.6 | 26.7 | 22.5 | |

| 77 | 36.5 | 33.5 | 28.0 | 23.2 | |

| 78 | 43.5 | 29.6 | 27.8 | 23.7 | |

| 78 | 32.5 | 29.7 | 26.3 | 23.7 | |

| 80 | 37.5 | 33.5 | 28.1 | 24.3 | |

| 80 | 30.6 | 28.4 | 30.9 | 24.3 | |

| 80 | 39.1 | 36.4 | 27.1 | 24.3 | |

| 83 | 48.0 | 35.8 | 30.3 | 25.3 | |

| 84 | 33.1 | 31.2 | 28.4 | 25.5 | |

| 85 | 33.7 | 34.7 | 31.0 | 25.9 | |

| 86 | 36.0 | 30.8 | 30.3 | 26.1 | |

| 87 | 44.7 | 37.8 | 31.4 | 26.5 | |

| 88 | 33.5 | 29.7 | 24.8 | 27.3 | |

| 89 | 47.4 | 48.8 | 36.8 | 27.7 | |

| 90 | 44.2 | 38.7 | 27.5 | 27.8 | |

| 91 | 58.1 | 44.8 | 32.9 | 28.7 | |

| 92 | 43.7 | 36.8 | 30.9 | 28.9 | |

| 93 | 55.9 | 45.9 | 37.3 | 29.1 | |

| 93 | 42.4 | 40.3 | 31.0 | 29.1 | |

| 95 | 65.6 | 50.2 | 39.7 | 29.5 | |

| 95 | 42.4 | 35.8 | 34.1 | 29.5 | |

| 97 | 30.9 | 28.2 | 34.3 | 29.7 | |

| 98 | 46.7 | 44.1 | 36.5 | 30.1 | |

| 99 | 37.8 | 37.2 | 32.2 | 30.4 | |

| 99 | 52.5 | 42.6 | 36.5 | 30.4 | |

| 101 | 38.0 | 33.6 | 30.4 | 30.8 | |

| 102 | 49.1 | 42.4 | 35.8 | 30.9 | |

| 103 | 38.8 | 38.8 | 32.2 | 31.1 | |

| 103 | 40.9 | 34.8 | 29.2 | 31.1 | |

| 105 | 41.2 | 34.2 | 31.3 | 31.2 | |

| 106 | 38.3 | 37.0 | 36.0 | 32.6 | |

| 107 | 38.7 | 39.7 | 36.0 | 32.9 | |

| 108 | 48.4 | 42.0 | 35.2 | 33.3 | |

| 109 | 40.3 | 32.9 | 30.9 | 34.0 | |

| 110 | - | 41.8 | 42.4 | 34.2 | |

| 111 | 52.3 | 43.2 | 35.0 | 34.3 | |

| 99 | - | - | - | 34.8 | |

| Global Hunger Index[7] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2018[9] |

| 113 | 42.7 | 45.2 | 48.5 | 35.4 | |

| 114 | 54.4 | 51.7 | 40.4 | 35.7 | |

| 115 | 52.0 | 45.8 | 42.8 | 37.6 | |

| 116 | 43.5 | 43.4 | 36.1 | 38.0 | |

| 117 | 43.2 | 41.7 | 34.5 | 39.7 | |

| 118 | 51.4 | 52.0 | 48.9 | 45.4 | |

| Global Hunger Index[7] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Country | 2000 | 2005 | 2010 | 2018[10] |

| 113 | 50.5 | 49.6 | 41.3 | 53.7 | |

— = Data are not available or not presented. Some countries did not exist in their present borders in the given year or reference period.

Countries are ranked according to 2018 GHI scores. Countries that have identical 2018 scores are given the same ranking (for example, Bulgaria and the Slovak Republic are both ranked 16th). The following countries could not be included because of lack of data: Bahrain, Bhutan, Burundi, Democratic Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea, Libya, Moldova, Qatar, Somalia, South Sudan, the Syrian Arab Republic, and Tajikistan.

Focus of the GHI 2018: Forced Migration and Hunger

The essay in the 2018 GHI report examines forced migration and hunger—two closely intertwined challenges that affect some of the poorest and most conflict-ridden regions of the world. Globally, there are an estimated 68.5 million displaced people, including 40.0 million internally displaced people, 25.4 million refugees, and 3.1 million asylum seekers. For these people, hunger may be both a cause and a consequence of forced migration. Support for food-insecure displaced people needs to be improved in four key areas: • recognizing and addressing hunger and displacement as political problems; • adopting more holistic approaches to protracted displacement settings involving development support; • providing support to food-insecure displaced people in their regions of origin; and • recognizing that the resilience of displaced people is never entirely absent and should be the basis for providing support.

The 2018 Global Hunger Index report presents recommendations for providing a more effective and holistic response to forced migration and hunger. These include focusing on those countries and groups of people who need the most support, providing long-term solutions for displaced people, and engaging in greater responsibility sharing at an international level.

Focus 2017: The Inequalities of Hunger

The 2017 highlights the uneven nature of progress made in reducing hunger worldwide and the ways in which inequalities of power lead to unequal nourishment.

Achieving the UN Sustainable Development Goals’ aim of “leaving no one behind” demands approaches to hunger and malnutrition that are both more sensitive to their uneven distribution and more attuned to the power inequalities that intensify the effects of poverty and marginalization on malnutrition. The report emphasizes the importance of using power analysis to name all forms of power that keep people hungry and malnourished; the significance of designing interventions strategically focused on where power is exerted; the need to empower the hungry and malnourished to challenge and resist loss of control over the food they eat.

Focus 2016: Getting to zero hunger

The 2016 Global Hunger Index (GHI) presents a multidimensional measure of national, regional, and global hunger, focusing on how the world can get to Zero Hunger by 2030.

The developing world has made substantial progress in reducing hunger since 2000. The 2016 GHI shows that the level of hunger in developing countries as a group has fallen by 29 percent. Yet this progress has been uneven, and great disparities in hunger continue to exist at the regional, national, and subnational levels.

The 2016 GHI emphasizes that the regions, countries, and populations most vulnerable to hunger and undernutrition have to be identified, so improvement can be targeted there, if the world community wants to seriously Sustainable Development Goal 2 on ending hunger and achieving food security.[GHI2016 3]

Focus 2015: Armed Conflict and Chronic Hunger

The chapter on hunger and conflict shows that the time of the great famines with more than 1 million people dead is over. There is, however, a clear connection between armed conflict and severe hunger. Most of the countries scoring worst in the 2015 GHI, are experiencing armed conflict or have in recent years. Still, severe hunger exists also without conflict present as the cases of several countries in South Asia and Africa show.

Since 2005 and increase in armed conflict can be seen. Unless armed conflicts can be reduced there is little hope for overcoming hunger.[GHI2015 1]

Focus of the GHI 2014: Hidden Hunger

Hidden hunger concerns over 200 million people worldwide. This micronutrient deficiency develops when humans do not take in enough micronutrients such as zinc, folate, iron and vitamins, or when their bodies cannot absorb them. Reasons include an unbalanced diet, a higher need for micronutrients (e.g. during pregnancy or while breast feeding) but also health issues related to sickness, infections or parasites.

The consequences for individuals can be devastating: these often include mental impairment, bad health, low productivity and death caused by sickness. In particular, children are affected if they do not absorb enough micronutrients in the first 1000 days of their lives (beginning with conception).[GHI2014 1]

Micronutrient deficiencies are responsible for an estimated 1.1 million of the yearly 3.1 million death caused by undernutrition in children. Despite the magnitude of the problem, it is still not easy to get precise data on the spread of hidden hunger. Macronutrient and micronutrient deficiencies cause a loss in global productivity of 1.4 to 2.1 billion US Dollars per year.[11]

Different measures exist to prevent hidden hunger. It is essential to ensure that humans maintain a diverse diet. The quality of produce is as important as the caloric input. This can be achieved by promoting the production of a wide variety of nutrient-rich plants and the creation of house gardens.

Other possible solutions are the industrial enrichment of food or biofortification of feedplants (e.g. vitamin A rich sweet potatoes). In the case of acute nutrient deficiency and in specific life phases, food supplements can be used. In particular, the addition of vitamin A leads to a better child survival rate.[GHI2014 2]

Generally, the situation concerning hidden hunger can only be improved when many measures intermesh. In addition to the direct measures described above, this includes the education and empowerment of women, the creation of better sanitation and adequate hygiene, and access to clean drinking water and health services.

Focus of the GHI 2013: Resilience to build food and nutrition security

Many of the countries, in which the hunger situation is "alarming" or "extremely alarming", are particularly prone to crises: In the African Sahel people experience yearly droughts. On top of that, they have to deal with violent conflict and natural calamities. At the same time, the global context becomes more and more volatile (financial and economic crises, food price crises).

The inability to cope with these crises leads to the destruction of many development successes that had been achieved over the years. In addition, people have even less resources to withstand the next shock or crises. 2.6 billion people in the world live with less than 2 USD per day. For them, a sickness in the family, crop failure after a drought or the interruption of remittances from relatives who live abroad can set in motion a downward spiral from which they cannot free themselves on their own.

It is therefore not enough to support people in emergencies and, once the crises is over, to start longer term development efforts. Instead, emergency and development assistance has to be conceptualized with the goal of increasing resilience of poor people against these shocks.

The Global Hunger Index differentiates three coping strategies. The lower the intensity of the crises, the less resources have to be used to cope with the consequences:[GHI2013 1]

- Absorption: Skills or resources, which are used to reduce the impact of a crisis without changing the lifestyle (e.g. selling some livestock)

- Adaptation: Once the capacity to absorb is exhausted, steps are taken to adapt the lifestyle to the situation without making drastic changes (e.g. using drought-resistant seeds).

- Transformation: If the adaptation strategies do not suffice to deal with the negative impact of the crises, fundamental, longer lasting changes to life and behavior have to be made (e.g. nomadic tribes become sedentary and become farmers because they cannot keep their herds).

Based on this analysis the authors present several policy recommendations:[GHI2013 2]

- Overcoming the institutional, financial and conceptual boundaries between humanitarian aid and development assistance.

- Elimination of policies that undermine people's resilience. Using the Right to Food as a basis for the development of new policies.

- Implementation of multi-year, flexible programs, which are financed in a way that enables multi-sectoral approaches to overcome chronic food crises.

- Communicating that improving resilience is cost effective and improves food and nutrition security, especially in fragile contexts.

- Scientific monitoring and evaluation of measures and programs with the goal to increase resilience.

- Active involvement of the local population in the planning and implementation of resilience increasing programs.

- Improvement of food especially of mothers and children through nutrition-specific and sensitive interventions to avoid that short-term crises lead to nutrition-related problems late in life or across generations.

Focus of the GHI 2012: Pressures on land, water and energy resources

Increasingly, Hunger is related to how we use land, water and energy. The growing scarcity of these resources puts more and more pressure on food security. Several factors contribute to an increasing shortage of natural resources:[GHI2012 1]

- Demographic change: The world population is expected to be over 9 billion by 2050. Additionally, more and more people live in cities. Urban populations feed themselves differently than inhabitants of rural areas; they tend to consume less staple foods and more meat and dairy products.

- Higher income and non-sustainable use of resources: As the global economy grows, wealthy people consume more food and goods, which have to be produced with a lot of water and energy. They can afford not to be efficient and wasteful in their use of resources.

- Bad policies and weak institutions: When policies, for example energy policy, are not tested for the consequences they have on the availability of land and water it can lead to failures. An example are the biofuel policies of industrialized countries: As corn and sugar are increasingly used for the production of fuels, there is less land and water for the production of food.

Signs for an increasing scarcity of energy, land and water resources are for example: growing prices for food and energy, a massive increase of large-scale investment in arable land (so-called land grabbing), increasing degradation of arable land because of too intensive land use (for example, increasing desertification), increasing number of people, who live in regions with lowering ground water levels, and the loss of arable land as a consequence of climate change. The analysis of the global conditions lead the authors of the GHI 2012 to recommend several policy actions:[12]

- Securing land and water rights

- Gradual lowering of subsidies

- Creation of a positive macroeconomic framework

- Investment in agriculture technology development to promote a more efficient use of land, water and energy

- Support for approaches, that lead to a more efficient use of land, water and energy along the whole value chain

- Preventing and overuse of natural resources through monitoring strategies for water, land and energy, and agricultural systems

- Improvement of the access to education for women and the strengthening of their reproductive rights to address demographic change

- Increase incomes, reduce social and economic inequality and promotion of sustainable lifestyles

- Climate change mitigation and adaptation through a reorientation of agriculture

Focus of the GHI 2011: Rising and volatile food prices

The report cites 3 factors as the main reasons for high volatility, or price changes, and price spikes of food:

- Use of the so-called biofuels, promoted by high oil prices, subsidies in the United States (over one third of the corn harvest of 2009 and 2010 respectively) and quota for biofuel in gasoline in the European Union, India and others.

- Extreme weather events as a result of Climate Change

- Future trading of agricultural commodities, for instance investments in fonds, which are speculating on price changes of agricultural products (2003: 13 Bn US Dollar, 2008: 260 Bn US Dollar), as well as increasing trade volume of these goods.

Volatility and prices increases are worsened according to the report by the concentration of staple foods in a few countries and export restrictions of these goods, the historical low of worldwide cereal reserves and the lack of timely information on food products, reserves and price developments. Especially this lack of information can lead to overreactions in the markets. Moreover, seasonal limitations on production possibilities, limited land for agricultural production, limited access to fertilizers and water, as well as the increasing demand resulting from population growth, puts pressure on food prices.

According to the Global Hunger Index 2011 price trends show especially harsh consequences for poor and under-nourished people, because they are not capable to react to price spikes and price changes. Reactions, following these developments, can include: reduced calorie intake, no longer sending children to school, riskier income generation such as prostitution, criminality, or searching landfills, and sending away household members, who cannot be fed anymore. In addition, the report sees an all-time high in the instability and unpredictability of food prices, which after decades of slight decrease, increasingly show price spikes (strong and short-term increase).[GHI2011 1][GHI2011 2]

At a national level, especially food importing countries (those with a negative food trade balance, are affected by the changing prices.

Focus of the GHI 2010: Early Childhood Under-nutrition

Under-nutrition among children has reached terrible levels. About 195 million children under the age of five in the developing world—about one in three children—are too small and thus underdeveloped. Nearly one in four children under age five—129 million—is underweight, and one in 10 is severely underweight. The problem of child under-nutrition is concentrated in a few countries and regions with more than 90 percent of stunted children living in Africa and Asia. 42% of the world's undernourished children live in India alone.

The evidence presented in the report[13] [14] shows that the window of opportunity for improving nutrition spans is the 1,000 days between conception and a child's second birthday (that is the period from -9 to +24 months). Children who are do not receive adequate nutrition during this period have increased risks to experiencing lifelong damage, including poor physical and cognitive development, poor health, and even early death. The consequences of malnutrition that occurred after 24 months of a child's life are by contrast largely reversible.[15]

Other activities

IFPRI is a partner in Compact2025, a partnership that develops and disseminates evidence-based advice to politicians and other decision-makers aimed at ending hunger and undernutrition in the coming 10 years.[16] The Compact2025 uses GHI data.

| 116 || style="text-align:left;" | Template:Country data Central African Republin || 43.9 || 43.6 ||36.8|| 38.3

See also

References

- ↑ "Global hunger worsening, warns UN". BBC (Europe). 14 October 2009. Retrieved 2010-08-22.

- ↑ "Map: The World's Hunger Problem". The Washington Post. 12 October 2015. Retrieved 2015-10-20.

- ↑ "2016 Global Hunger Index: Revealed - the worst countries in the world at feeding their own people". The Independent. 17 October 2016. Retrieved 2016-12-01.

- ↑ von Grebmer, Klaus; Bernstein, Jill; Hossain, Naomi; Brown, Tracy; Prasai, Nilam; Yohannes, Yisehac; Patterson, Fraser; Sonntag, Andrea; Zimmermann, Sophia-Marie; Towey, Olive; and Foley, Connell. 2017. 2017 Global Hunger Index: The inequalities of hunger: Synopsis. Washington, D.C.; Bonn; and Dublin: International Food Policy Research Institute, Welthungerhilfe, and Concern Worldwide.

- ↑ FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations). 2016. Food Security Indicators ((Updated February 9, 2016). . Rome.

- ↑ UN IGME (UN Inter-agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation). 2015. Child Mortality Estimates Info, Under-five Mortality Estimates. (Updated September 9, 2015). .

- 1 2 3 K. von Grebmer, J. Bernstein, A. de Waal, N. Prasai, S. Yin, Y. Yohannes: 2015 Global Hunger Index - Armed Conflict and the Challenge of Hunger. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide. October 2018.

- ↑ http://www.globalhungerindex.org/results-2018/

- ↑ http://www.globalhungerindex.org/results-2018/

- ↑ http://www.globalhungerindex.org/results-2018/

- ↑ Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2013 The State of Food and Agriculture: Food Systems for Better Nutrition. Rome.

- ↑ IFPRI/ Welthungerhilfe/ Concern. 2012. 2012 Global Hunger Index. Issue Brief No. 70. Washington, DC

- ↑ Victora, C. G., L. Adair, C. Fall, P. C. Hallal, R. Martorell, L. Richter und H. Singh Sachdev for the Maternal and Child Undernutrition Study Group. 2008. Maternal and child undernutrition: Consequences for adult health and human capital. "The Lancet" 371 (9609): 340–57

- ↑ Victora, C. G., M. de Onis, P. C. Hallal, M. Blössner und R. Shrimpton. 2010. Worldwide timing of growth faltering: Revisiting implications for interventions. "Pediatrics" 125 (3): 473.

- ↑ IFPRI/ Concern/ Welthungerhilfe: 2010 Global Hunger Index The challenge of hunger: Focus on the crisis of child undernutrition. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin. October 2011.

- ↑ Compact2025: Ending hunger and undernutrition. 2015. Project Paper. IFPRI: Washington, DC.

von Grebmer, Klaus; Bernstein, Jill; Nabarro, David; Prasai, Nilam; Amin, Shazia; Yohannes, Yisehac; Sonntag, Andrea; Patterson, Fraser; Towey, Olive; and Thompson, Jennifer. 2016. 2016 Global hunger index: Getting to zero hunger. Bonn Washington, DC and Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, International Food Policy Research Institute, and Concern Worldwide.

K. von Grebmer, J. Bernstein, A. de Waal, N. Prasai, S. Yin, Y. Yohannes: 2015 Global Hunger Index - Armed Conflict and the Challenge of Hunger. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide. October 2015.

K. von Grebmer; A. Saltzman; E. Birol; D. Wiesmann; N. Prasai; S. Yin; Y. Yohannes; P. Menon; J. Thompson; A. Sonntag. 2014. 2014 Global Hunger Index: The challenge of hidden hunger. Bonn, Washington, DC, and Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide.

Prasai, Nilam. 2014. Global Hunger Index 2014: Interactive Tool Web application created with Tableau software 8.2. Retrieved from http://www.ifpri.org/tools/2014-ghi-map (access date).

von Grebmer, Klaus; Headey, Derek; Béné, Christophe; Haddad, Lawrence; Olofinbiyi, Tolulope; Wiesmann, Doris; Fritschel, Heidi; Yin, Sandra; Yohannes, Yisehac; Foley, Connell; von Oppeln, Constanze; and Iseli, Bettina. 2013. 2013 Global Hunger Index: The challenge of hunger: Building resilience to achieve food and nutrition security. Bonn, Washington, DC, and Dublin: Welthungerhilfe, IFPRI, and Concern Worldwide.

Klaus von Grebmer, Claudia Ringler, Mark W. Rosegrant, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Doris Wiesmann, Heidi Fritschel, Ousmane Badiane, Maximo Torero, Yisehac Yohannes (IFPRI); Jennifer Thompson (Concern Worldwide); Constanze von Oppeln, Joseph Rahall (Welthungerhilfe and Green Scenery): 2012 Global Hunger Index - The challenge of hunger: Ensuring sustainable food security under land, water, and energy stresses. Washington, DC. October 2012.

- ↑ Chapter 3: 'Sustainable food security under land, water, and energy stresses', pages 25-26

Klaus von Grebmer, Maximo Torero, Tolulope Olofinbiyi, Heidi Fritschel, Doris Wiesmann, Yisehac Yohannes (IFPRI); Lilly Schofield, Constanze von Oppeln (Concern Worldwide und Welthungerhilfe): 2011 Global Hunger Index - The challenge of hunger: Taming Price Spikes and Excessive Food Price Volatility. Bonn, Washington D. C., Dublin. October 2011.

- ↑ Chapter 3: Combating Hunger in a World of High and Volatile Food Prices

- ↑ Chapter 4: The Impacts of Food Price Spikes and Volatility at Local Levels, pages 20–41

Further reading

- Alkire, S. und M. E. Santos. 2010. Multidimensional Poverty Index: 2010 data. Oxford Poverty and Human Development Initiative. .

- Wiesmann, Doris (2004): An international nutrition index: concept and analyses of food insecurity and undernutrition at country levels. Development Economics and Policy Series 39. Peter Lang Verlag.

External links

- Data from the 2016 GHI

- 2015 Global Hunger Index: Fact Sheet

- Global Hunger Index: Interactive Maps

- GHI 2014: Hunger in the shadows of the Millennium Development Goals. IFPRI Blog, 13 October 2014. Accessed on 20 October 2015.

- 2013 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger: Building resilience to achieve food and nutrition security

- 2012 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger: Ensuring sustainable food security under land, water, and energy stresses

- 2011 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger: Taming price spikes and excessive food price volatility

- 2010 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger: Focus on the crisis of child undernutrition

- 2009 Global Hunger Index: The Challenge of Hunger: Focus on Financial Crisis and Gender Inequality

- Welthungerhilfe Hunger Issue Page

- Concern Worldwide

- How are we doing on poverty and hunger reduction? A new measure of country performance