Giant-cell arteritis

| Giant-cell arteritis | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | Temporal arteritis, cranial arteritis,[1] Horton disease,[2] senile arteritis,[1] granulomatous arteritis[1] |

| |

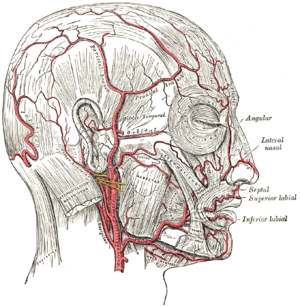

| The arteries of the face and scalp. | |

| Specialty | Rheumatology, emergency medicine |

| Symptoms | Headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, difficulty opening the mouth[3] |

| Complications | Blindness, aortic dissection, aortic aneurysm, polymyalgia rheumatica[4] |

| Usual onset | Age greater than 50[4] |

| Causes | Inflammation of the small blood vessels within the walls of larger arteries[4] |

| Diagnostic method | Based on symptoms and blood tests, confirmed by biopsy of the temporal artery[4] |

| Differential diagnosis | Takayasu arteritis,[5] stroke, primary amyloidosis[6] |

| Treatment | Steroids, bisphosphonates, proton pump inhibitor[4] |

| Prognosis | Life expectancy (typically normal)[4] |

| Frequency | ~ 1 in 15,000 people a year (> 50 years old)[2] |

Giant-cell arteritis (GCA), also called temporal arteritis, is an inflammatory disease of blood vessels.[4] Symptoms may include headache, pain over the temples, flu-like symptoms, double vision, and difficulty opening the mouth.[3] Complication can include blockage of the artery to the eye with resulting blindness, aortic dissection, and aortic aneurysm.[4] GCA is frequently associated with polymyalgia rheumatica.[4]

The cause is unknown.[2] The underlying mechanism involves inflammation of the small blood vessels that occur within the walls of larger arteries.[4] This mainly affects arteries around the head and neck, though some in the chest may also be affected.[4][7] Diagnosis is suspected based on symptoms, blood tests, and medical imaging, and confirmed by biopsy of the temporal artery.[4] However, in about 10% of people the temporal artery is normal.[4]

Treatment is typically with high doses of steroids, such as prednisone.[4] Once symptoms have resolved the dose is then decreased by about 15% per month.[4] Once a low dose is reached, the taper is slowed further over the subsequent year.[4] Other medications that may be recommended include bisphosphonates to prevent bone loss and a proton pump inhibitor to prevent stomach problems.[4]

It affects about 1 in 15,000 people over the age of 50 a year.[2] The condition typically only occurs in those over the age of 50 being most common among those in their 70s.[4] Females are more often affected than males.[4] Those of northern European descent are more commonly affected.[5] Life expectancy is typically normal.[4] The first description of the condition occurred in 1890.[1]

Signs and symptoms

It is more common in women than in men by a ratio of 2:1 and more common in those of Northern European descent, as well as those residing at higher (northern/southern) latitudes. The mean age of onset is >55 years, and it may be rarer in those younger than 55 years of age.

People present with:

- bruits

- fever

- headache[8]

- tenderness and sensitivity on the scalp

- jaw claudication (pain in jaw when chewing)

- tongue claudication (pain in tongue when chewing) and necrosis[9][10]

- reduced visual acuity (blurred vision)

- acute visual loss (sudden blindness)

- diplopia (double vision)

- acute tinnitus (ringing in the ears)

- polymyalgia rheumatica (in 50%)[11]

The inflammation may affect blood supply to the eye; blurred vision or sudden blindness may occur. In 76% of cases involving the eye, the ophthalmic artery is involved causing arteritic anterior ischemic optic neuropathy.[12]

Giant-cell arteritis may present with atypical or overlapping features.[13] Early and accurate diagnosis is important to prevent ischemic vision loss. Therefore, this condition is considered a medical emergency.[13]

Associated conditions

The varicella-zoster virus antigen was found in 74% of temporal artery biopsies that were GCA-positive, suggesting that the VZV infection may trigger the inflammatory cascade.[14]

The disorder may coexist (in a half of cases)[11] with polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), which is characterized by sudden onset of pain and stiffness in muscles (pelvis, shoulder) of the body and is seen in the elderly. GCA and PMR are so closely linked that they are often considered to be different manifestations of the same disease process. Other diseases associated with temporal arteritis are systemic lupus erythematosus, rheumatoid arthritis, and severe infections.

Giant-cell arteritis can involve branches of the aorta as well, leading to an aortic aneurysm or dissection. For this reason, patients should be followed with serial chest X-rays.

Mechanism

The pathological mechanism seems to start when dendritic cells in the vessel wall recruit T cells and macrophages to form granulomatous infiltrates. T helper 17 cells involved with interleukin (IL) 6, IL-17 and IL-21 play a critical part; this pathway is suppressed with glucocorticoids.[4]

Diagnosis

Physical exam

- Palpation of the head reveals prominent temporal arteries with or without pulsation.

- The temporal area may be tender.

- Decreased pulses may be found throughout the body

- Evidence of ischemia may be noted on fundal exam.

Laboratory tests

- LFTs, liver function tests, are abnormal particularly raised ALP- alkaline phosphatase

- Erythrocyte sedimentation rate, an inflammatory marker, >60 mm/hour (normal 1–40 mm/hour).

- C-reactive protein, another inflammatory marker, may be elevated.

- Platelets may also be elevated.

Biopsy

The gold standard for diagnosing temporal arteritis is biopsy, which involves removing a small part of the vessel under local anesthesia and examining it microscopically for giant cells infiltrating the tissue.[15] Since the blood vessels are involved in a patchy pattern, there may be unaffected areas on the vessel and the biopsy might have been taken from these parts. Unilateral biopsy of a 1.5–3 cm length is 85-90% sensitive (1 cm is the minimum).[16] A negative result does not definitively rule out the diagnosis. Characterised as intimal hyperplasia and medial granulomatous inflammation with elastic lamina fragmentation with a CD 4+ predominant T cell infiltrate, currently biopsy is only considered confirmatory for the clinical diagnosis, or one of the diagnostic criteria.[10]

Imaging studies

Radiological examination of the temporal artery with ultrasound yields a halo sign. Contrast-enhanced brain MRI and CT is generally negative in this disorder. Recent studies have shown that 3T MRI using super high resolution imaging and contrast injection can non-invasively diagnose this disorder with high specificity and sensitivity.[17]

Treatment

Corticosteroids, typically high-dose prednisone (1 mg/kg/day), must be started as soon as the diagnosis is suspected (even before the diagnosis is confirmed by biopsy) to prevent irreversible blindness secondary to ophthalmic artery occlusion. Steroids do not prevent the diagnosis from later being confirmed by biopsy, although certain changes in the histology may be observed towards the end of the first week of treatment and are more difficult to identify after a couple of months.[18] The dose of prednisone is lowered after 2–4 weeks, and slowly tapered over 9–12 months. Tapering may require two or more years. Oral steroids are at least as effective as intravenous steroids,[19] except in the treatment of acute visual loss where intravenous steroids appear to offer significant benefit over oral steroids.[20] It is unclear if adding a small amount of aspirin is beneficial or not as it has not been studied.[21] Injections of tocilizumab may also be used.[22]

Terminology

The terms "giant-cell arteritis" and "temporal arteritis" are sometimes used interchangeably, because of the frequent involvement of the temporal artery. However, other large vessels such as the aorta can be involved.[23] Giant-cell arteritis is also known as "cranial arteritis" and "Horton's disease."[24] The name (giant-cell arteritis) reflects the type of inflammatory cell involved.[25]

References

- 1 2 3 4 Nussinovitch, Udi (2017). The Heart in Rheumatic, Autoimmune and Inflammatory Diseases: Pathophysiology, Clinical Aspects and Therapeutic Approaches. Academic Press. p. 367. ISBN 9780128032688. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- 1 2 3 4 "Orphanet: Giant cell arteritis". www.orpha.net. Archived from the original on 14 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- 1 2 "Giant Cell Arteritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 Solomon, Caren G.; Weyand, Cornelia M.; Goronzy, Jörg J. (2014). "Giant-Cell Arteritis and Polymyalgia Rheumatica". New England Journal of Medicine. 371 (1): 50–7. doi:10.1056/NEJMcp1214825. PMC 4277693. PMID 24988557.

- 1 2 Johnson, Richard J.; Feehally, John; Floege, Jurgen (2014). Comprehensive Clinical Nephrology E-Book. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 300. ISBN 9780323242875. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- ↑ Ferri, Fred F. (2010). Ferri's Differential Diagnosis E-Book: A Practical Guide to the Differential Diagnosis of Symptoms, Signs, and Clinical Disorders. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 195. ISBN 0323081630. Archived from the original on 2017-10-22.

- ↑ "Giant Cell Arteritis". National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases. 13 April 2017. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 21 October 2017.

- ↑ Moutray, Tanya N.; Williams, Michael A.; Best, Jayne L. (2008). "Suspected giant cell arteritis: a study of referrals for temporal artery biopsy". Canadian Journal of Ophthalmology. 43 (4): 445–8. doi:10.3129/i08-070. PMID 18711459.

- ↑ Sainuddin, Sajid; Saeed, Nadeem R. (2008). "Acute bilateral tongue necrosis – a case report". British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery. 46 (8): 671–2. doi:10.1016/j.bjoms.2008.03.027. PMID 18499311.

- 1 2 Zadik, Yehuda; Findler, Mordechai; Maly, Alexander; Rushinek, Heli; Czerninski, Rakefet (2011). "A 78-year-old woman with bilateral tongue necrosis". Oral Surgery, Oral Medicine, Oral Pathology, Oral Radiology, and Endodontology. 111 (1): 15–9. doi:10.1016/j.tripleo.2010.09.001. PMID 21176820.

- 1 2 Hunder, Gene G. "Polymyalgia rheumatica and giant cell (temporal) arteritis". uptodate.com. Wolters Kluwer. Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 23 September 2015.

- ↑ Hayreh (April 3, 2003). "Ocular Manifestations of GCA". University of Iowa Health Care. Archived from the original on 2007-10-25. Retrieved 2007-10-15.

- 1 2 Rana, AbdulQayyum; Saeed, Usman; Khan, OsamaA; Qureshi, Abdul; Paul, Dion (2014). "Giant cell arteritis or tension-type headache?: A differential diagnostic dilemma". Journal of Neurosciences in Rural Practice. 5 (4): 409–11. doi:10.4103/0976-3147.140005. PMC 4173245. PMID 25288850.

- ↑ Gilden, Don; White, Teresa; Khmeleva, Nelly; Heintzman, Anna; Choe, Alexander; Boyer, Philip J.; Grose, Charles; Carpenter, John E.; Rempel, April; Bos, Nathan; Kandasamy, Balasubramaniyam; Lear-Kaul, Kelly; Holmes, Dawn B.; Bennett, Jeffrey L.; Cohrs, Randall J.; Mahalingam, Ravi; Mandava, Naresh; Eberhart, Charles G.; Bockelman, Brian; Poppiti, Robert J.; Tamhankar, Madhura A.; Fogt, Franz; Amato, Malena; Wood, Edward; Durairaj, Vikram; Rasmussen, Steve; Petursdottir, Vigdis; Pollak, Lea; Mendlovic, Sonia; Chatelain, Denis; Keyvani, Kathy; Brueck, Wolfgang; Nagel, Maria A. (2015). "Prevalence and distribution of VZV in temporal arteries of patients with giant cell arteritis". Neurology. 84 (19): 1948–55. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000001409. PMC 4433460. PMID 25695965.

- ↑ Cahais, J.; Houdart, R.; Lupinacci, R. M.; Valverde, A. (June 2017). "Operative technique: Superficial temporal artery biopsy". Journal of Visceral Surgery. 154 (3): 203–207. doi:10.1016/j.jviscsurg.2017.05.001. ISSN 1878-7886. PMID 28601496.

- ↑ Ypsilantis, E.; Courtney, E. D.; Chopra, N.; Karthikesalingam, A.; Eltayab, M.; Katsoulas, N.; Tang, T. Y.; Ball, R. Y. (2011). "Importance of specimen length during temporal artery biopsy". British Journal of Surgery. 98 (11): 1556–60. doi:10.1002/bjs.7595. PMID 21706476.

- ↑ Bley, T.A.; Uhl, M.; Carew, J.; Markl, M.; Schmidt, D.; Peter, H.-H.; Langer, M.; Wieben, O. (2007). "Diagnostic Value of High-Resolution MR Imaging in Giant Cell Arteritis". American Journal of Neuroradiology. 28 (9): 1722–7. doi:10.3174/ajnr.A0638. PMID 17885247.

- ↑ Font, Ramon L; Prabhakaran, Venkatesh C (2007). "Histological parameters helpful in recognising steroid-treated temporal arteritis: an analysis of 35 cases". British Journal of Ophthalmology. 91 (2): 204–9. doi:10.1136/bjo.2006.101725. PMC 1857614. PMID 16987903.

- ↑ "BestBets: Steroids and Temporal Arteritis". Archived from the original on 2009-02-27.

- ↑ Chan, Colin C K; Paine, Mark; O'Day, Justin (2001). "Steroid management in giant cell arteritis". The British Journal of Ophthalmology. 85 (9): 1061–4. doi:10.1136/bjo.85.9.1061. PMC 1724128. PMID 11520757.

- ↑ Mollan, Susan P; Sharrack, Noor; Burdon, Mike A; Denniston, Alastair K; Mollan, Susan P (2014). "Aspirin as adjunctive treatment for giant cell arteritis". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (8): CD010453. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD010453.pub2. PMID 25087045.

- ↑ "Press Announcements - FDA approves first drug to specifically treat giant cell arteritis". www.fda.gov. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ↑ Walter, MA; Melzer, RA; Graf, M; Tyndall, A; Müller-Brand, J; Nitzsche, EU (2005). "[18F]FDG-PET of giant-cell aortitis". Rheumatology. 44 (5): 690–1. doi:10.1093/rheumatology/keh551. PMID 15728420.

- ↑ James, William D.; Berger, Timothy G.; et al. (2006). Andrews' Diseases of the Skin: clinical Dermatology. Saunders Elsevier. p. 840. ISBN 0-7216-2921-0.

- ↑ "giant cell arteritis" at Dorland's Medical Dictionary

External links

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| External resources |

- Hayreh, Sohan Singh; Zimmerman, Bridget (2003). "Management of Giant Cell Arteritis". Ophthalmologica. 217 (4): 239–59. doi:10.1159/000070631. PMID 12792130.