Ghetto tax

| Part of a series on |

| Economics |

|---|

|

|

|

|

By application |

|

Notable economists |

|

Lists |

|

Glossary |

|

A ghetto tax is a term used to describe how people with low incomes pay higher prices for goods and services, particularly those living in poverty-stricken areas.[1][2][3]

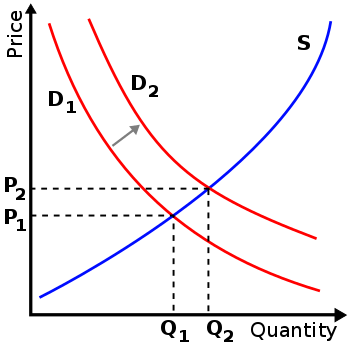

Economic principles

A ghetto tax is not literally a tax. It is a situation in which people pay higher costs for equivalent goods or services simply because they are poor or live in a poor area. A paper by the Brookings Institution, titled From Poverty, Opportunity: Putting the Market to Work for Lower Income Families,[4] is widely cited as a study into ghetto taxes, although the report itself does not use the term.[1][5][6]

The problem of ghetto taxes is closely associated with mobility; one study in the United States showed that higher prices might be prevalent in some neighbourhoods, but people with access to a car would have more access to affordable goods and services elsewhere, whilst those without a car would bear the brunt of higher local prices.[2][7]

Examples

- Credit services: Lower income consumers are much more reliant upon alternative financial services that are more expensive, such as check cashers and payday lenders, pawnshops, and auto-title lenders.[5]

- Financial Services: Customers who can maintain a minimum bank balance can avoid fees, such as monthly fees, or qualify for higher interest rates on their deposits. There are also fewer ATMs in poor areas, and often they are third-party machines that charge fees to all users.

- Health care: Poorer people have worse and more expensive health conditions, and poorer neighborhoods have fewer doctors' offices and medical facilities.

- Transportation: Poorer neighborhoods tend to have fewer nearby jobs, requiring longer commutes and more transportation costs in time and money. This can also decrease employment opportunities, increasing unemployment.[8] Public transportation also tends to underserve poorer areas.

- Groceries: Grocery stores in poor neighbourhoods are smaller than in large neighbourhoods; lacking economies of scale, they are more expensive as well. Low income households may find transportation to cheaper out-of-town supermarkets too costly, or too burdensome, with refrigerated foods needing to last a car or bus ride home.[2][3] Some poor households may not be able to afford large quantities, and hence lose out on bulk discounts.[9] Poorer areas are also more likely to be food deserts, with only convenience stores available, which have higher prices than supermarkets and a higher proportion of unhealthy foods.

- Household appliances: In the USA, lower-income households are more likely to spend more on a given household item. Also, rent-to-own and consumer financing terms tend to have high interest rates and are mostly used by people unable to pay the full costs of their purchases up-front.[5]

- Utilities: Poor people are more likely to pay higher prices for long-distance phone calls.[10]

- Cigarettes: In some areas it is possible to buy (legally or illegally) single cigarettes. Purchasers are typically poor (and perhaps unable to afford a whole pack of cigarettes), but per-cigarette cost is higher, thus making smoking a more expensive habit for poorer people. This is in addition to the fact that (in many countries) the prevalence of smoking is already concentrated in lower socioeconomic groups.[11][12]

See also

References

- 1 2 Eckholm, Erik (19 July 2006). "Study Documents 'Ghetto Tax' Being Paid by the Urban Poor". The New York Times. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- 1 2 3 Talukdar, Debabrata (2008). "Cost of Being Poor: Retail Price and Consumer Price Search Differences across Inner-City and Suburban Neighborhoods". Journal of Consumer Research. 35 (3): 457. doi:10.1086/589563. JSTOR 589563.

- 1 2 Brown, DeNeen L. (18 May 2009). "The High Cost of Poverty: Why the Poor Pay More - washingtonpost.com". The Washington Post. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ "From Poverty, Opportunity: Putting the Market to Work for Lower Income Families". Brookings Institution. July 2006. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- 1 2 3 Fellowes, Matt (July 2006). "From Poverty, Opportunity: Putting the Market to Work for Lower Income Families" (PDF). Brookings Institution.

- ↑ Katz, Rob (3 August 2006). "The Ghetto Tax". NextBillion.net. Retrieved 9 June 2015.

- ↑ "Georgetown Law Faculty Blog: Market Failures Mean The Poor Still Pay More". 20 July 2006. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ "The growing distance between people and jobs in metropolitan America". Brookings Institution. Retrieved 25 July 2016.

- ↑ Attanasio, Orazio P.; Frayne, Christine (January 2006). "Do the Poor Pay More?" (PDF). Institute for Fiscal Studies.

- ↑ Hausman, Jerry A.; Sidak, J. Gregory (April 2004). "Why Do the Poor and the Less-Educated Pay More for Long-Distance Calls?". Contributions to Economic Analysis & Policy. 3 (1). doi:10.2202/1538-0645.1210.

- ↑ Giskes, K; Kunst, A E; Ariza, C; Benach, J; Borrell, C; Helmert, U; Judge, K; Lahelma, E; et al. (1 July 2007). "Applying an Equity Lens to Tobacco-Control Policies and Their Uptake in Six Western-European Countries". Journal of Public Health Policy. 28 (2): 261–280. doi:10.1057/palgrave.jphp.3200132. PMID 17585326. Retrieved 14 August 2011.

- ↑ Klontoff E, Fritz J, Landrine H, Riddle R, Tully-Payne L. The problem and sociocultural context of single-cigarette sales. J Am Med Assoc. 1994;271:618–620.

External links

Fellowes, Matt (July 2006). "From Poverty, Opportunity: Putting the Market to Work for Lower Income Families" (PDF). Brookings Institution.