Geosmin

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

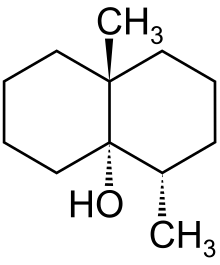

(4S,4aS,8aR)-4,8a-dimethyloctahydronaphthalen-4a(2H)-ol | |

| Other names

(4S,4aS,8aR)-4,8a-Dimethyl-1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8-octahydronaphthalen-4a-ol; 4,8a-Dimethyl-decahydronaphthalen-4a-ol; Octahydro-4,8a-dimethyl-4a(2H)-naphthalenol | |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.039.294 |

PubChem CID |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C12H22O | |

| Molar mass | 182.31 g·mol−1 |

| Boiling point | 270 to 271 °C (518 to 520 °F; 543 to 544 K) |

| Hazards | |

| Flash point | 104 °C (219 °F; 377 K) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| Infobox references | |

Geosmin is an organic compound with a distinct earthy flavor and aroma produced by certain bacteria, and is responsible for the earthy taste of beets and a contributor to the strong scent (petrichor) that occurs in the air when rain falls after a dry spell of weather or when soil is disturbed.[1] In chemical terms, it is a bicyclic alcohol with formula C12H22O, a derivative of decalin. Its name is derived from the Greek γεω- "earth" and ὀσμή "smell".

Production

Geosmin is produced by the gram-positive bacteria Streptomyces and various cyanobacteria, and released when these microorganisms die.[2][3][4] Communities whose water supplies depend on surface water can periodically experience episodes of unpleasant-tasting water when a sharp drop in the population of these bacteria releases geosmin into the local water supply. Under acidic conditions, geosmin decomposes into odorless substances.[5]

In 2006, the biosynthesis of geosmin by a bifunctional Streptomyces coelicolor enzyme was unveiled.[6][7] A single enzyme, geosmin synthase, converts farnesyl diphosphate to geosmin in a two-step reaction.

Streptomyces coelicolor is the model representative of a group of soil-dwelling bacteria with a complex lifecycle involving mycelial growth and spore formation. Besides the production of volatile geosmin, it also produces many other complex molecules of pharmacological interest; its genome sequence is available at the Sanger Institute.[8]

Effects

The human nose is extremely sensitive to geosmin and is able to detect it at concentrations as low as 5 parts per trillion.[9]

Geosmin is responsible for the muddy smell in many commercially important freshwater fish such as carp and catfish.[10][11] Geosmin combines with 2-methylisoborneol, which concentrates in the fatty skin and dark muscle tissues. Geosmin breaks down in acid conditions; hence, vinegar and other acidic ingredients are used in fish recipes to help reduce the muddy flavor.[12]

See also

References

- ↑ The earth's perfume, Protein Spotlight, Issue 35, June 2003.

- ↑ Izaguirre G, Taylor WD. (2004). "A guide to geosmin- and MIB-producing cyanobacteria in the United States". Water Sci Technol. 49 (9): 19–24. PMID 15237602.

- ↑ Zaitlin B, Watson SB. (2006). "Actinomycetes in relation to taste and odour in drinking water: Myths, tenets and truths". Water Res. 40 (9): 1741–53. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2006.02.024. PMID 16600325.

- ↑ Suurnäkki S, Gomez-Saez GV, Rantala-Ylinen A, Jokela J, Fewer DP, Sivonen K. (2015). "Identification of geosmin and 2-methylisoborneol in cyanobacteria and molecular detection methods for the producers of these compounds". Water Res. 68 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1016/j.watres.2014.09.037. PMID 25462716.

- ↑ Gerber, NN; Lechevalier, HA (November 1965). "Geosmin, an earthly-smelling substance isolated from actinomycetes". Applied Microbiology. 13 (6): 935–8. PMC 1058374. PMID 5866039.

- ↑ Jiang, J.; He, X.; Cane, D.E. (2006). "Geosmin biosynthesis. Streptomyces coelicolor germacradienol/germacrene D Synthase converts farnesyl diphosphate to geosmin". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 128 (25): 8128–8129. doi:10.1021/ja062669x. PMID 16787064.

- ↑ Jiang, J.; He, X.; Cane, D.E. (2007). "Biosynthesis of the earthy odorant geosmin by a bifunctional Streptomyces coelicolor enzyme". Nat. Chem. Biol. 3 (11): 711–5. doi:10.1038/nchembio.2007.29. PMC 3013058. PMID 17873868.

- ↑ "The genome of Streptomyces coelicolor A3(2) producing geosmin". Sanger Institute. Retrieved 2009-01-31.

- ↑ Polak, E.H.; Provasi, J. (1992). "Odor sensitivity to geosmin enantiomers". Chemical Senses. 17: 23. doi:10.1093/chemse/17.1.23.

- ↑ Vallod, D.; Cravedi, J. P.; Hillenweck, A.; Robin, J. (2007-04-03). "Analysis of the off-flavor risk in carp production in ponds in Dombes and Forez (France)". Aquaculture International. 15 (3–4): 287–298. doi:10.1007/s10499-007-9080-7. ISSN 0967-6120.

- ↑ Lovell, Richard T.; Lelana, Iwan Y.; Boyd, Claude E.; Armstrong, Martin S. (1986-05-01). "Geosmin and Musty-Muddy Flavors in Pond-Raised Channel Catfish". Transactions of the American Fisheries Society. 115 (3): 485–489. doi:10.1577/1548-8659(1986)115<485:gamfip>2.0.co;2. ISSN 0002-8487.

- ↑ Winkler, Lawrence (2012-08-06). Westwood Lake Chronicles. Lawrence Winkler. ISBN 9780991694105.

Further reading

- Bear, I.J.; R.G. Thomas (1964). "Nature of argillaceous odour". Nature. 201 (4923): 993–995. doi:10.1038/201993a0.

- Bear, I.J.; R.G. Thomas (1965). "Petrichor and plant growth". Nature. 207 (5005): 1415–1416. doi:10.1038/2071415a0.