George Moses Horton

George Moses Horton (1798–1884) was an African-American poet from North Carolina, the first to be published in the Southern United States. His book The Hope of Liberty was published in 1829 while he was still enslaved. He is one of a few African American writers to have their poetry published while still enslaved. He did not gain freedom until 1865, late during the Civil War.

Biography

Horton was born into slavery on William Horton's plantation in 1798 in Northampton County, North Carolina.[1] He was the sixth of ten children; the names of his parents are lost to history.[2] His owner relocated when Horton was a very young child; in 1800, he and several family members were moved with the master to a tobacco farm in rural Chatham County. In 1814 William Horton gave the youth as property to his relative James Horton.[1] In 1819, the estate was broken up, and George Horton's family was separated. (His poem "Division of an Estate", written years later, reflected on this experience).[2]

Horton disliked farm work and in his limited free time, he taught himself to read using spelling books, the Bible, and hymnals.[2] Learning poetry and snippets of literature, Horton composed poems in his mind. As a young adult, Horton delivered produce to the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, where he composed and recited poems for students, some of whom transcribed his pieces. Horton also composed poems, usually love poems, by commission for individual students at 25 or 50 cents each.[1] Considering the difficulty of earning income from poetry, Horton was likely one of the few professional poets in the South at the time.[3]

In 1928 a number of newspapers in North Carolina and beyond discussed Horton's work.[4] In 1829, his poems were published in a collection titled The Hope of Liberty, which was intended to raise funds for his release from slavery.[5] The book, funded by the politically liberal journalist Joseph Gales, was published the same year as David Walker's An Appeal to the Coloured Citizens of the World.[6] Horton is believed to be the first Southern black to publish poetry.[1] Though he knew how to read, he published the book before he had learned how to write. As he recalled, "I fell to work in my head, and composed several undigested pieces."[7]

By 1832, Horton had learned to write, helped by Caroline Lee Hentz, who was a writer and the wife of a professor. She also helped gain publication of at least two of his poems in a newspaper.[1] Horton had composed a poem on the death of Hentz's first child. As he recalled: "She was extremely pleased with the dirge which I wrote on the death of her much lamented primogenial infant, and for which she gave me much credit and a handsome reward. Not being able to write myself, I dictated while she wrote."[7] She sent another of Horton's poems to her hometown newspaper in Lancaster, Massachusetts, where it was published on April 8, 1828, as "Liberty and Slavery".[2]

Horton's first book was republished under the title Poems by a Slave in 1837. It was collected with a biography and poetry by Phillis Wheatley a year later in a book called Memoir and Poems of Phillis Wheatley, a Native African and Slave: Also Poems by a Slave.[8] The book was published by Boston-based publisher and abolitionist Isaac Knapp. This is believed to be the first complete collection of Wheatley's poems in book form.[9] Newspapers again took note of Horton.[10]

In 1845, Horton published another book of poetry, The Poetical Works of George M. Horton, The Colored Bard of North-Carolina, To Which Is Prefixed The Life of the Author, Written by Himself. The moniker, "Colored Bard of North-Carolina", was coined by his new publisher. Newspapers took notice again in December–January 1849–1850,[11] and advertisements for the book were printed in a Hillsborough newspaper from 1852 into 1853.[12] Horton was given direct credit for some poems published in newspapers in 1857 and 1858.[13] A newspaper article in Raleigh in August 1865 on Horton was entitled "Naked Genius", of his last book,.[14]

Horton gained the admiration of North Carolina Governor John Owen, influential newspapermen Horace Greeley and William Lloyd Garrison, and numerous Northern abolitionists.

Sometime in the 1830s, Horton had married an enslaved woman owned by Franklin Snipes in Chatham County. The couple had two children, Free and Rhody. Little else is known about the family.[15]

Horton had written about his interest in the new nation of Liberia. A few of the abolitionist papers suggested raising money to buy his freedom and pay for his passage, so that Horton could migrate to Liberia. He was not emancipated until 1865, however; when he met the Ninth Cavalry from Michigan. A young officer with that group, William H. S. Banks, collaborated with Horton on the collection Naked Genius the same year.[8]

At the age of 68, Horton moved to Pennsylvania as a freeman, where he continued to write poetry for local newspapers. His poem, "Forbidden to Ride on the Street Cars", expressed his disappointment in the unjust treatment of blacks after emancipation.[15] Arriving in Philadelphia before the summer of 1866,[16] he wrote Sunday school stories on behalf of friends who lived in the city. His exact death location and date are unknown.[8] At least one researcher suggests Horton moved to Liberia at some point.[15]

Poetry

After Horton's first poem was published in the Lancaster, Massachusetts Gazette, his works were published in other newspapers, such as the Register in Raleigh, North Carolina, and Freedom's Journal in New York City.[2] Horton's poetic style was typical of contemporary European poetry and was similar to poems written by free white contemporaries, likely a reflection of his reading and his work for commission.[3] He wrote both sonnets and ballads. His earlier works focused on his life in slavery. Such topics, however, were more generalized and not necessarily based on his personal experience. He referred to his life on "vile accursed earth" and the "drudg'ry, pain, and toil" of life, as well as his oppression "because my skin is black".[3]

His first collection was focused on the issues of slavery and bondage. He did not gain enough in sales from that book to purchase his freedom; in his second book, he mentions slavery only twice.[17] The change in theme is also likely due to the more restrictive climate in the South in the years leading up to the Civil War.[15]

His later works, especially those written after his emancipation, expressed rural and pastoral themes. Like other early black American writers such as Jupiter Hammon and Phillis Wheatley, Horton was deeply influenced by the Bible and African-American religion.[17]

The earliest known critical commentary on Horton's writing is from 1909 by UNC professor Collier Cobb. He dismissed Horton's antislavery themes, saying: "George never really cared for more liberty than he had, but was fond of playing to the grandstand.".[18]

Legacy

Building towards his remembrance, biographies began to appear. The first was by Kemp Plummer Battle in May 1888,[19] then President of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. J. Donald Cameron noted Horton among notable North Carolina poets in 1890; a speech that was reported several times in some newspapers.[20] Battle reprised his thoughts on Horton in his history of the University published in 1907.[21] In 1909 UNC professor Collier Cobb wrote a paper on Horton,[22] which he published in 1925 at his own cost.[23] Horton was remembered at UNC on the occasion of the visit of James Weldon Johnson.[24] The centennial of his first book was noted in the New York Age after it was noted in Greensboro.[25]

- In 1927 Winston-Salem, North Carolina opened a segregated library for blacks in a YWCA building; it was named for George Moses Horton.[26]

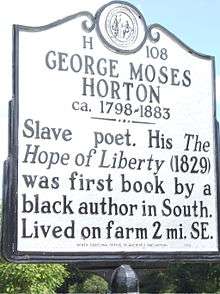

- In the 1990s, North Carolina erected a historical marker about Horton near where he had lived. (See photo)

- In 1996 Horton was inducted into the North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame.[27]

- Also in 1996, the George Moses Horton Society for the Study of African American Poetry was founded.[27]

- In 1997, Horton was named as Historic Poet Laureate of Chatham County, North Carolina.[27]

- In 2006, UNC Chapel Hill named a dormitory for George Moses Horton; it is believed to be the first university dormitory in the country to be named for a slave.[28]

- In 2015 author/illustrator Don Tate published Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton, an illustrated biography for children. The Wilson Library at UNC hosted the national launch of the book on September 3, 2015.[29]

Published works

- The Hope of Liberty (1829)

- Poems by a Slave (1837)

- The Poetical Works of George M. Horton (1845)

- Naked Genius (1865, with William H. S. Banks)

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Johnson, Lonnell E. "George Moses Horton" in African American Authors, 1745-1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook (Emmanuel S. Nelson, editor). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000: 239. ISBN 0-313-30910-8

- 1 2 3 4 5 Page, Amanda. "George Moses Horton" in The North Carolina Roots of African American Literature: An Anthology (William L. Andrews, editor). The University of North Carolina Press, 2006: 45. ISBN 0-8078-2994-3

- 1 2 3 O'Brien, Michael. Intellectual Life and the American South, 1810-1860. The University of North Carolina Press, 2010: 181. ISBN 978-0-8078-3400-8

- ↑

- "Poetry". Fayetteville Weekly Observer. Fayetteville, NC. 7 Aug 1828. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "From the Raleigh Register; George M. Horton". North-Carolina Free Press. Halifax, NC. 15 Aug 1828. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "George M Horton". Statesman and Gazette. Natchez, MI. 11 Sep 1828. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "George M Horton". Farmer's Herald. St Johnsbury, VT. 11 Nov 1828. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ Brown, Sterling (1937). Negro Poetry and Drama. Washington, DC: Westphalia Press. p. 6. ISBN 1935907549.

- ↑ Gordon, Dexter B. Black Identity: Rhetoric, Ideology, and Nineteenth-Century Black Nationalism. Southern Illinois University, 2003: 2009. ISBN 0-8093-2485-7

- 1 2 Hager, Christopher. Word by Word: Emancipation and the Act of Writing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2013: 69. ISBN 978-0-674-05986-3

- 1 2 3 Johnson, Lonnell E. "George Moses Horton" in African American Authors, 1745-1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook (Emmanuel S. Nelson, editor). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000: 240. ISBN 0-313-30910-8

- ↑ Cavitch, Max. American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press, 2007: 193. ISBN 978-0-8166-4892-4

- ↑ George Horton (3 Apr 1839). "From the Washington Whig,... On Transitory Pleasures". The Greensboro Patriot. Greensboro, NC. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑

- "The "Standard" this quaintly..." The Raleigh Register. Raleigh, NC. 29 Dec 1849. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "The "Standard" this quaintly..." Weekly Raleigh Register. Raleigh, NC. 2 Jan 1850. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 10 Mar 1852. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's Poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 17 Mar 1852. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 14 Apr 1852. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 5 May 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 12 May 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 26 May 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 9 Jun 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 16 Jun 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 23 Jun 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 30 Jun 1852. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 1 Sep 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 22 Sep 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 6 Oct 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 13 Oct 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 27 Oct 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 17 Nov 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 8 Dec 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 15 Dec 1852. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 5 Jan 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 12 Jan 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 26 Jan 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 2 Feb 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 9 Feb 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 16 Feb 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 2 Mar 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Horton's poems". The Hillsborough Recorder. Hillsborough, NC. 6 Apr 1853. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑

- George M. Horton (16 May 1857). "Poetry; To my lady". The Chapel Hill Gazette. Chapel Hill, NC. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- George M Horton (17 Apr 1858). "Reflections". Anti-Slavery Bugle. Lisbon, OH. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ "Naked Genius". The Daily Progress. Raleigh, NC. 31 Aug 1865. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Page, Amanda. "George Moses Horton" in The North Carolina Roots of African American Literature: An Anthology (William L. Andrews, editor). The University of North Carolina Press, 2006: 46. ISBN 0-8078-2994-3

- ↑ "An unusually intelligent contraband". The Evening Telegraph. Philadelphia, PA. 23 Aug 1866. p. 5. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- 1 2 Johnson, Lonnell E. "George Moses Horton" in African American Authors, 1745-1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook (Emmanuel S. Nelson, editor). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000: 241. ISBN 0-313-30910-8

- ↑ Johnson, Lonnell E. "George Moses Horton" in African American Authors, 1745-1945: Bio-bibliographical Critical Sourcebook (Emmanuel S. Nelson, editor). Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 2000: 242. ISBN 0-313-30910-8

- ↑ Kemp Plummer Battle (May 1888). "George Horton, the slave poet". North Carolina University Magazine. 7 (5): 229–32. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ "North Carolina Poets". Asheville Citizen-Times. Asheville, NC. 18 Sep 1890. p. 1. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "North Carolina poets". The Asheville Weekly Citizen. Asheville, NC. 25 Sep 1890. p. 2. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "Colonel Cameron's poets of North Carolina". The Asheville Democrat. Asheville, NC. 2 Oct 1890. p. 4. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ Kemp Plummer Battle (1907). "University dependents and laborers". History of the University of North Carolina. 1 (Electronic ed.). Raleigh, NC: Edwards & Broughton Printing Company. p. 603.

- ↑ "Prof. Collier Cobb's ..." The Charlotte Observer. Charlotte, NC. 20 Dec 1909. p. 3. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- Collier Cobb (Oct 1909). "An American man of letters". University of North Carolina Magazine. Vol. 27 no. 1. p. 2532. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑

- "A curious item..." The Courier-Journal. Louisville, KY. 8 Mar 1925. p. 34. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- "A curious item ..." Austin American-Statesman. Austin, Texas. 8 Mar 1925. p. 16. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ DDC (12 Apr 1927). "The sun rises". The Daily Tar Heel. Chapel Hill, NC. p. 2. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ Raymond Adams (21 Dec 1929). "North Carolina's pioneer negro poet". The New York Age. New York, NY. p. 7. Retrieved Mar 23, 2018.

- ↑ Rawls, Molly Grogan. Winston-Salem: From the Collection of Frank B. Jones Jr. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing, 2006: 62. ISBN 978-0-7385-4324-6

- 1 2 3 Sherman, Joan R. "Horton, George Moses" in African American Lives (Henry Louis Gates and Evelyn Brooks Higginbotham, editors). New York: Oxford University Press, 2004: 415. ISBN 0-19-516024-X

- ↑ Baker, Elizabeth (September 2, 2015). "Former slave poet honored in book". The Daily Tar Heel. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

- ↑ "Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton Book Launch Sept. 3 at Wilson Library". UNC Library News and Events. August 12, 2015. Retrieved 22 October 2015.

Further reading

- Schuessler, Jennifer (September 25, 2017). "In a Lost Essay, a Glimpse of an Elusive Poet and Slave". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to George Moses Horton. |

- Life of George M. Horton. The Colored Bard of North Carolina. Hillsborough: Heartt, 1845.

- The Poetical Works of George M. Horton: The Colored Bard of North Carolina: To Which is Prefixed the Life of the Author, Written by Himself. Hillsborough [N.C.]: Printed by D. Heartt, 1845.

- "The George Moses Horton Project: Celebrating a Triumph of Literacy" by Marjorie Hudson

- The George Moses Horton Project, Chatham Arts Council

- George Moses Horton listing, North Carolina Literary Hall of Fame

- “Poet: The Remarkable Story of George Moses Horton," Tate, Don, author-illustrator; Peachtree Publishers; Atlanta, Georgia, 2015. ISBN 978-1561458257.