Freud family

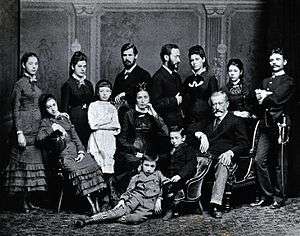

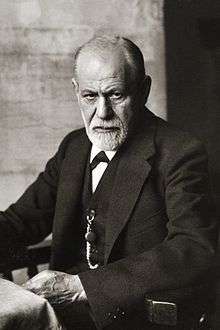

The family of Sigmund Freud, the pioneer of psychoanalysis, lived in Austria and Germany until the 1930s before emigrating to England, Canada and the United States. Several of Freud's descendants have become well known in different fields.

Freud's parents and siblings

Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) was born to Jewish Galician parents in the Moravian town of Freiberg, in the then Austrian Empire (now Příbor in the Czech Republic).[1] He was the eldest child of Jacob Freud (1815–1896),[2] a wool merchant, and his third wife Amalia Nathansohn (1835–1930). Jacob Freud was born in Tysmenitz, Galicia (now Tysmenytsia, in Ukraine), the eldest child of Schlomo and Peppi (Pessel), née Hoffmann, Freud.[3] His two brothers Abae (c1815-c1885) and Josef (1825-1897) had difficulties that concerned the family, the former because of his mentally incapacitated children, the latter because his business dealings came under criminal investigation.[4]

Jacob Freud had two surviving children from his first marriage to Sally Kanner (1829–1852):

- Emanuel (1833–1914)

- Philipp (1836–1911)

Jacob's second marriage (1852–1855) to Rebecca (family of origin uncertain) was childless.

Amalia Freud was the daughter of Jacob Nathansohn (1805–1865) and Sara Wilenz from Brody, Galicia (now part of Ukraine). They later moved to Vienna. Her brother Hermann (1822–1895), who was a stockbroker in Odessa, was Freud's favourite uncle. She had three other brothers: Nathan (b. c.1825), Adolf (c.1830–1862) and Julius (c.1837–1858).[5] Jacob and Amalia Freud had eight children:[6]

- Sigmund (birth name Sigismund Schlomo; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939)

- Julius (October 1857 – 15 April 1858)

- Anna (31 December 1858 – 11 March 1955)

- Regina Debora (nickname Rosa; 21 March 1860 – 1943)

- Marie (nickname Mitzi; 22 March 1861 – 1942)

- Esther Adolfine (nickname Dolfi; 23 July 1862 – 1943)

- Pauline Regine (nickname Pauli; 3 May 1864 – 1942)

- Alexander Gotthold Ephraim (19 April 1866 – 23 April 1943)

Julius Freud died in infancy.

Anna married Ely Bernays (1860–1921), the elder brother of Sigmund's wife Martha. There were four daughters: Judith (1885–1977), Lucy (1886–1980), Hella (1893–1994), Martha (1894–1979) and one son, Edward (1891–1995). In 1892 the family moved to the United States where Edward Bernays became a major influence in modern public relations. He married Doris E. Fleischman (1891–1980) who became known as a prominent feminist activist. Their daughters are Doris Bernays Held (b. 1929), a psychotherapist who married Richard Held (1922-2016) a neuroscientist, and Anne Bernays (b. 1930) a writer and editor, as was her husband, Justin Kaplan (1925–2014).

Rosa (Regina Deborah Graf-Freud) married a lawyer, Heinrich Graf (1852–1908). Their son, Hermann (1897–1917) was killed in the First World War; their daughter, Cacilie (1899–1922), committed suicide after an unhappy love affair. Rosa died in Treblinka in 1943.

Mitzi (Maria Moritz-Freud) married her cousin Moritz Freud (1857–1922). There were three daughters: Margarethe (1887–1981), Lily (1888–1970), Martha (1892–1930) and one son, Theodor (1904–1923) who died in a drowning accident. Martha, who was known as Tom and dressed as a man, worked as a children’s book illustrator. After the suicide of her husband, Jakob Seidman, a journalist, she took her own life. Their daughter, Angela, was sent to live with relatives in Haifa.[7] Lily became an actress and in 1917 married the actor Arnold Marlé.[8] They subsequently adopted Angela. Mitzi died in the Maly Trostinets extermination camp in 1942.

Dolfi (Esther Adolfine Freud) did not marry and remained in the family home to care for her parents. She died in Theresienstadt concentration camp in 1943.

Pauli (Pauline Regine Winternitz-Freud) married Valentine Winternitz (1859–1900) and emigrated to the United States where their daughter Rose Beatrice (1896–1969) was born. After the death of her husband she and her daughter returned to Europe.[9] Rose (known as Rosi) married Ernst Waldinger, a poet, in 1923. They moved to New York City after the war where a daughter, Ruth, was born.[10] Pauli died in the Maly Trostinets extermination camp in 1942.

Alexander Freud married Sophie Sabine Schreiber (1878–1970). Their son, Harry (1909–1968), emigrated to the United States where he married Leli Margaret Horn.[11]

Both Freud’s half-brothers emigrated to Manchester, England, shortly before the rest of the Freud family moved to Vienna in 1860.

Emanuel Freud married Maria Milow (1836–1923) in Freiberg where their first two children were born: John (b. 1856, disappeared pre-1919), the "inseparable playmate" of Freud’s early childhood;[12] and Pauline (1855–1944). Their other children were born in Manchester: Matilda (1862–1868), Harriet (1865–1868), Bertha (1866–1940), Henrietta (1866 infant death) and Soloman (1870–1945, known as Sam). None of the children married.

Philipp Freud married Bloomah Frankel (b. 1845 Birmingham, d.1925 Manchester). There were two children: Pauline (1873–1951) who married Fred Hartwig (1881–1958); and Morris (b. 1875 Manchester, d.1938 Port Elizabeth, South Africa). The death of the childless Pauline in 1951 marked the end of the Manchester Freuds.[13]

Freud visited his half-brothers and their families in England twice, in 1875 while still a student, and again in 1908.[14] He kept in touch through a regular correspondence with Sam Freud. They would eventually meet again in London in 1938.[15]

Persecution and emigration

The systematic persecution of Jews by Nazi Germany and the ensuing Holocaust had a profound effect on the family. Four of Freud's five sisters died in concentration camps: in 1942 Mitzi Freud (eighty-one) and Paula Winternitz (seventy-eight) were transported to Theresienstadt and taken from there to the Maly Trostinets extermination camp, near Minsk, where they were murdered. In 1943 Dolfi Freud died in Theresienstadt of internal bleeding, probably due to advanced starvation and Rosa Graf (eighty-two) was deported to Treblinka, where she was killed.[16] Freud's brother, Alexander, escaped with his family to Switzerland shortly before the Anschluss and they subsequently emigrated to Canada. Freud's sons Oliver, a civil engineer, and Ernst Ludwig, an architect, lived and worked in Berlin until Hitler came to power in Germany in 1933 after which they fled with their families to France and England respectively. Oliver Freud and his wife later emigrated to the United States. Their daughter Eva Freud had remained in France and died there of an infection contracted during an abortion.[17]

Freud and his remaining family left Nazi-occupied Vienna in 1938 after Ernest Jones, the then President of the International Psychoanalytic Association, secured immigration permits for them to move to Britain. Permits were also secured for Freud’s housekeeper and maid, his doctor, Max Schur and his family, as well as a number of Freud's colleagues and their families. Freud's grandson, Ernst Halberstadt, was the first to leave Vienna, initially for Paris, before going on to London where after the war he would adopt the name Ernest Freud and train as a psychoanalyst. Next to leave for Paris were Ernestine, Sophie and Walter Freud, the wife and children of Freud's eldest son, Martin. Walter joined his father in London. His mother and sister remained in France and subsequently emigrated to the United States. His maternal grandmother, Ida Drucker, was deported from Biarritz in 1942 and died in Auschwitz.[18] Freud’s sister-in-law, Minna Bernays, was the first to leave for London early in May 1938. She was followed by his son, Martin, on 14 May and then his daughter Mathilde and her husband, Robert Hollitscher, on 24 May. Freud, his wife and daughter, Anna, left Vienna on 4 June, accompanied by their household staff and a doctor. Their arrival at Victoria Station, London on 6 June attracted widespread press coverage.[19] Freud’s Vienna consulting room was replicated in faithful detail in the new family home, 20 Maresfield Gardens in Hampstead, North London.

The war years

After Freud's death in 1939, Martha and Anna Freud made their home available to relatives and friends fleeing the Nazi occupation of Europe.[20] In 1941, following the death of Martha's sister, Minna, Dorothy Burlingham (1891–1979) became a permanent member of the household. From their first meeting in Vienna in 1925, Anna and Dorothy developed “intimate relations that closely resembled those of lesbians”, though Anna “categorically denied the existence of a sexual relationship”.[21] Dorothy was a patient of Freud’s and her four children, Bob, Mary (Mabbie), Katrina and Michael, were among the first of Anna’s after she had begun her own psychoanalytic practice. They collaborated in establishing the Hampstead War Nursery which provided therapy and residential care for children whose lives had been disrupted by the war. Their work laid the foundations for the post-war Hampstead Clinic (later renamed the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families).[22]

Martin and Walter Freud were both interned in 1940 as enemy aliens. Following a change in government policy on internment, both were subsequently recruited to the Pioneer Corps. After the war, denied recognition as a (Vienna trained) lawyer by the British legal profession, Martin Freud ran a tobacconist’s in Bloomsbury.[23] His autobiographical memoir of Freud family life in Vienna, Glory Reflected, was published in 1952.[24] Walter Freud was deported to an internment camp in New South Wales, Australia. On his return to England in 1941 he was recruited to the Pioneer Corps and subsequently to the SOE. In April 1945 he was parachuted behind enemy lines in Austria. Advised to change his name in case of capture, he refused, declaring : “I want the Germans to know a Freud is coming back”. He narrowly survived separation from his comrades and took the leading role in securing the surrender of the strategically important Zeltweg aerodrome in southern Austria.[25] When the war ended he was assigned to war crimes investigation work in Germany. Given the fate of his great aunts and maternal grandmother at the hands of the Nazis, he was particularly pleased to help secure the prosecution of directors of the firm that supplied Zyklon B gas to the concentration camps, two of whom were executed for war crimes. In 1946 he left the army with the rank of major. The following year he was granted British citizenship and resumed his career as an industrial chemist.[26]

Retribution for the murder of his aunts was also a concern for Alexander Freud’s son Harry. He arrived in post-war Vienna as a US army officer to investigate the circumstances of their deportation and helped track down and bring before the courts Anton Sauerwald, the Nazi commissar charged with the supervision of the Freuds’ assets. Sauerwald gained early release from prison in 1947 when, at the request of his wife, Anna Freud intervened on his behalf, revealing that he had, by concealing evidence of Freud's Swiss bank account, "used his office as our appointed commissar in such a manner as to protect my father".[27]

Freud's children and descendants

Sigmund Freud married Martha Bernays (1861–1951) in 1886. Martha was the daughter of Berman Bernays (1826–1879) and Emmeline Philipp (1830–1910). Her grandfather, Isaac Bernays (1792–1849), was a Chief Rabbi of Hamburg. Two of her uncles were prominent academics: Jakob Bernays (1824–1881) was a professor of classics at the University of Bonn; Michael Bernays (1834–1897) was a professor of German literature at the University of Munich. Her sister, Minna Bernays (1865–1941), became a permanent member of the Freud household after the death of her fiancé in 1895.

Sigmund and Martha Freud had six children and eight grandchildren:[28]

- Mathilde Freud (1887–1978) married Robert Hollitscher (1875–1959), and had no children

- Jean-Martin Freud (1889–1967, known as Martin Freud) married Ernestine (Esti) Drucker (1896–1980), and had 2 children:

- Anton Walter Freud (1921–2004) married Annette Krarup (1925–2000) and had 3 children[29]

- David Freud (born 1950, later Lord Freud), married Cilla Dickinson and had 3 children:

- Andrew Freud

- Emily Freud

- Juliet Freud

- Ida Freud (born 1952), married N. Fairbairn

- Caroline Freud (born 1955), married N. Penney

- David Freud (born 1950, later Lord Freud), married Cilla Dickinson and had 3 children:

- Sophie Freud (born 1924) married Paul Loewenstein (1921–1992), and had 3 children:[30][31]

- Andrea Freud Loewenstein

- Dania Loewenstein, married S. Jekel

- George Loewenstein

- Anton Walter Freud (1921–2004) married Annette Krarup (1925–2000) and had 3 children[29]

- Oliver Freud (1891–1969) married Henny Fuchs (1892–1971), and had 1 child:

- Eva Freud (1924–1944)

- Ernst Ludwig Freud (1892–1970) married Lucie Brasch (1896–1989), and had 3 children:

- Stephan Gabriel Freud (1921–2015, known as Stephen Freud)[32] married (i) Lois Blake (born 1924); (ii) Christine Ann Potter (born 1927). From his marriage to Lois Blake he had 1 child:

- Dorothy Freud

- Lucian Michael Freud (1922–2011) married (i) Kathleen Garman (1926–2011), 2 children; (ii) Lady Caroline Blackwood (1931–1996). He also had 4 children by Suzy Boyt, 4 by Katherine McAdam (died 1998), 2 by Bernardine Coverley (died 2011), 1 by Jacquetta Eliot, Countess of St Germans and 1 by Celia Paul. His children include:[33][34]

- Annie Freud (born 1948)

- Annabel Freud (born 1952)

- Alexander Boyt (born 1957)

- Jane McAdam Freud (born 1958)

- Paul McAdam Freud (born 1959)

- Rose Boyt

- Lucy McAdam Freud (born 1961) married Peter Everett; 2 children

- Bella Freud (born 1961) married James Fox; 1 child

- Isobel Boyt (born 1961)

- Esther Freud (born 1963) married David Morrissey; 3 children

- David McAdam Freud (born 1964), 4 children. Partner of Debbi Mason

- Susie Boyt (born 1969) married to Tom Astor; 2 children

- Francis Michael Eliot (born 1971)

- Frank Paul (born 1984); 1 child

- Clemens Rafael Freud (1924–2009, later Sir Clement Raphael Freud) married June Flewett (stage name Jill Raymond)[35] in 1950 and had 5 children:[36]

- Nicola Freud, married to Richard Allen, had 5 children:

- Tom Freud (born 1973)[37]

- Jack Freud (born 1980), married to Kate Melhuish

- Martha Freud (born 1983)

- Max Freud (born 1986)

- Harry Freud (born 1986)

- Dominic Freud (born 1956) married Patty Freud, and had 3 children, Nicholas Freud, Joshua Freud, and Sophie Freud.

- Emma Freud (born 1962) partner of Richard Curtis, and had 4 children

- Matthew Freud (born 1963) married: (i) Caroline Hutton, and had 2 children; (ii) Elisabeth Murdoch, and had 2 children

- Ashley Freud (adopted nephew)[38]

- Nicola Freud, married to Richard Allen, had 5 children:

- Stephan Gabriel Freud (1921–2015, known as Stephen Freud)[32] married (i) Lois Blake (born 1924); (ii) Christine Ann Potter (born 1927). From his marriage to Lois Blake he had 1 child:

- Sophie Freud (1893–1920. Died in the inter-war influenza epidemic) married Max Halberstadt (1882–1940), and had 2 children:

- Ernst Halberstadt (1914–2008, also known as Ernest Freud)[39] married Irene Chambers (born 1920), and had 1 child:

- Colin Peter Freud (1956–1987)

- Heinz Halberstadt (1918–1923, also known as Heinele. Died from tuberculosis)

- Ernst Halberstadt (1914–2008, also known as Ernest Freud)[39] married Irene Chambers (born 1920), and had 1 child:

- Anna Freud (1895–1982)

References

- ↑ Gresser, Moshe (1994). Dual Allegiance: Freud As a Modern Jew. SUNY Press. p. 225.

- ↑ Hergenhahn, B. R. (2005). An introduction to the history of psychology. Thomson Wadsworth. p. 475.

- ↑ Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016). Freud: In His Time and Ours. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 581.

- ↑ Jones 1953, p. 4

- ↑ Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016). Freud: In His Time and Ours. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. p. 560.

- ↑ Clark 1980, pp. 1–2

- ↑ Young-Bruehl 2008, pp. 96, 194

- ↑ Arnold Marlé on IMDb

- ↑ Cohen 2009, pp. 205–207, 233

- ↑ Young-Bruehl 2008, pp. 193, 400

- ↑ "Register of Harry Freud's papers" (PDF). Library of Congress. Retrieved 16 October 2011.

- ↑ Jones 1953, p. 9

- ↑ Ferris, Paul Dr Freud: A Life, London: Sinclair-Stevenson 1975, pp. 243–44.

- ↑ Clark 1980, pp. 36, 252

- ↑ Cohen 2009, p. 176

- ↑ Benveniste, Daniel (2015) The Interwoven Lives of Sigmund, Anna and W. Ernest Freud: Three Generations of Psychoanalysis IPBooks.net. Kindle Edition pp. 279-81

- ↑ Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016), Freud: In His Time and Ours Harvard University Press, p. 401

- ↑ Fry 2009, p. 176

- ↑ Fry 2009, p. 93

- ↑ Young-Bruehl 2008, p. 280

- ↑ Roudinesco (2016), p. 249

- ↑ Young-Bruehl 2008, pp. 246–50

- ↑ Fry 2009, p. 192

- ↑ Martin Freud, Glory Reflected, London: Angus and Robertson, 1952.

- ↑ Fry 2009, pp. 143, 161–65

- ↑ Fry 2009, pp. 173–76, 189

- ↑ Cohen 2009, pp. 2, 213

- ↑ Clark 1980, pp. 1–2

- ↑ "Walter Freud obituary". The Guardian. 9 March 2004. Retrieved 24 April 2009.

- ↑ English, Bella (3 January 2002). "Freudian split". Boston Globe. Archived from the original on 21 June 2002.

- ↑ "Freud's offspring lead noted lives". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. 6 February 2008. Retrieved 16 April 2009.

- ↑ Adam Lusher (12 July 2008). "Stephen Freud Interview". Telegraph. Retrieved 2 November 2014.

- ↑ "Did Lucian Freud love his art more than his children?". Daily Mail. 23 July 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ "My life as Lucian Freud's love child". Daily Telegraph. 20 June 2011. Retrieved 29 April 2012.

- ↑ Jill Raymond on IMDb

- ↑ "Meet the Freuds". Evening Standard. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 25 April 2009.

- ↑ "People, Jun. 10, 1974". Time. 10 June 1974. Retrieved 25 April 2009. (Subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "A multi-talented miserabilist". Daily Express. 17 April 2009. Retrieved 30 April 2009.

- ↑ Benveniste, Daniel (December 2008). "Obituary: W. Ernest Freud (1914–2008)" (PDF). International Psychoanalysis. 17.

Bibliography

- Clark, Ronald W. (1980). Freud: the Man and His Cause. London: Jonathan Cape.

- Cohen, David (2009). The Escape of Sigmund Freud. London: JR Books.

- Fry, Helen (2009). Freuds' War. Stroud: The History Press.

- Jones, Ernest (1953). Sigmund Freud: Life and Work (Vol 1: The Young Freud 1856–1900)

|format=requires|url=(help). London: Hogarth Press. - Roudinesco, Elizabeth (2016). Freud: In His Time and Ours. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Young-Bruehl, Elizabeth (2008). Anna Freud. Yale University Press.

External links

- Maria Helena Rowell: Sigmund Freud and his Family at the Wayback Machine (archived October 27, 2009)

- Sigmund Freud and his Family on Rodovid