French frigate Magicienne (1778)

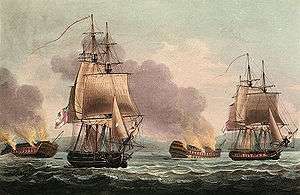

HMS Magicienne and HMS Acasta at the Battle of San Domingo. | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | Magicienne |

| Namesake: | "Sorceress" |

| Ordered: | 7 February 1777 |

| Builder: | Toulon |

| Laid down: | 6 August 1777 |

| Launched: | 1 August 1778 |

| Commissioned: | October 1778 |

| Captured: | 2 September 1781 |

| Name: | Magicienne |

| Acquired: | 2 September 1781 by capture |

| Honours and awards: | Naval General Service Medal with clasp "St. Domingo"[1] |

| Fate: | Scuttled on 24 August 1810 |

| General characteristics | |

| Class and type: | Magicienne class frigate |

| Displacement: | 600 tonnes & 1260 tonnes fully loaded |

| Length: | 44.2 m (145 ft) |

| Beam: | 11.2 m (37 ft) |

| Draught: | 5.2 m (17 ft) (22 French feet) |

| Armament: | |

| Armour: | Timber |

Magicienne was a frigate of the French Navy, lead ship of her class. The British captured her in 1781 and she served with the Royal Navy until her crew burned her in 1810 to prevent her capture after she grounded at Isle de France (now Mauritius). During her service with the Royal Navy she captured several privateers and participated in the Battle of San Domingo.

French service and capture

Magicienne was built to a design by Joseph-Marie-Blaise Coulomb at Toulon. She was the first of 12 vessels built to her design.

She served in Orvilliers' fleet under captain Brun de Boades. HMS Chatham captured her on 2 September 1781 off Cape Ann. In the action the French lost 60 men killed and 40 wounded; the British lost one man killed and one man wounded.[2] She was described as being of 800 tons, 36 guns and 280 men.[3]

A prize crew took her to Halifax where she was recommissioned in the Royal Navy as HMS Magicienne under Thomas Graves, on the North America station. He then sailed her to Jamaica in December.[4]

British service

On 15 July 1782, Magicienne and Prudent captured three French merchant vessels carrying sugar from Martinique to Europe. These were the ship Tea Bloom, the snow Balmboom, and the brig Juno. Juno was also carrying rum.[5]

On 2 January 1783, Magicienne, met the Sibylle.[Note 1] The ships fought inconclusively, reducing each other to wrecks before parting. In September 1783 Magicienne was paid off and fitted for ordinary at Chatham on 30 October.[4]

French Revolutionary Wars

On 29 April Magicienne was in company with Aquilon, Diamond, Minerva, Syren, Camilla, and Childers, when Acquilon captured the Mary.[6]

On 1 November 1796, Magicienne, under the command of Captain William Henry Ricketts, captured the French brig Cerf Volant[7] (enseigne de vaisseau Camau), off San Domingo. Cerf Volant was flying a flag of truce and had on board a midshipman and several British seamen, prisoners from Hindostan, to give the appearance that Cerf Volant was a cartel.[Note 2] She was carrying delegates from the Southern Department of St. Domingo to the French Legislative Body, and hidden dispatches for the Directory General,[8] that a search the next day uncovered. The hidden dispatches violated the truce flag and made Cerf Volant a legitimate prize. The search also uncovered a box of money.[9] Though Cerf-Volant was only three years old, the Royal Navy did not take her into service.[Note 3]

In early 1797, HMS Magicienne captured two privateers named Poisson Volant. One was armed with 12 guns and had a crew of 80 men, and the other was armed with five guns and had a crew of 50 men.[11] One was captured on 13 January, and the other on 16 February. Bounty bills (head money) was paid in September 1827.[Note 4] A later account narrates that Poisson Volant was a Dutch privateer, out of Curacao, and that Magicienne sent her into Jamaica to be condemned as a prize.

In late 1797 or early 1798, Magicienne, the troopship Regulus, and the brig-sloop Diligence captured the French privateer Brutus, of nine guns.[13]

After the crew of Hermione mutinied and murdered her captain, Hugh Pigot, in 1797, Magicienne was involved in the efforts to capture the mutineers and bring them to trial.

On 23 November 1800 Captain Sir Richard Strachan in Captain chased a French convoy in to the Morbihan where it sheltered under the protection of shore batteries and a 24-gun corvette. Magicienne was able to force the corvette Réolaise onto the shore at Port Navalo.[14] The hired armed cutters Suworow, Nile and Lurcher then towed in four boats with a cutting-out party of seamen and marines from Captain and Magicienne. Although the cutting-out party landed under heavy grape and small arms fire, it was able to set the corvette on fire; shortly thereafter Réolaise blew up. Only one British seaman, a crewman from Suworow, was killed.[15] However, Suworow's sails and rigging were so badly cut up that Captain had to tow her.[16]

In January 1801, Magicienne, with Doris in sight, captured in the Channel the French letter of marque Huron, which was returning from Mauritius with a highly valuable cargo of ivory, cochineal, indigo, tea, sugar, pepper, cinnamon, ebony, etc. Ogilvy described her as a "remarkable fine Ship, fails well, is pierced for Twenty Guns, had Eighteen mounted, but threw thorn all overboard except Four during the Chace; I think her a Vessel well calculated for His Majesty's Service."[17][Note 5]

Napoleonic Wars

On 24 July 1804 Amethyst, while in company with Magicienne, captured the Agnela.[19]

Early in March 1805, Magicienne and Reindeer sent two boats each, under the command of Lieutenant John Kelly Tudor of Reindeer, to cut out a 4-gun schooner from under a battery in Aguadilla Bay, Puerto Rico.

In 1806, while under the command of Captain Adam Mackenzie, she cruised in the Caribbean. On 25 January 1806, Magicienne was in company with Penguin in the Mona Passage when Magicienne captured the Spanish packet ship Carmen after a chase of 12 hours. Carmen was pierced for 14 guns but carrying only two, and had a crew of 18 men under the command of an officer of the same rank as a commander in the British Navy.[20]

Magicienne joined John Thomas Duckworth's squadron on 5 February, which led to her taking part in the Battle of San Domingo. Duckworth sent Magicienne and Acasta to reconnoitre, and it was they that signaled that the French were at anchor, but getting under way. Duckworth formed up the smaller ships, Acasta, Magicienne, Kingfisher and Epervier, windward of the line-of-battle ships to keep them out of the action.[21]

Donegal forced the surrender of the Brave and directed Acasta to take possession of her, whilst the Donegal moved on to engage the other French ships. Brave was one of the three that the British captured, the other two being the Jupiter and the Alexandre. Their captains drove two French ships, the flagship, Impérial, and the Diomède, on shore between Nizao and Point Catalan, their hulls broadside to the beach and their bottoms stove in by the reefs that lay offshore, to prevent their capture.

On 8 February Duckworth sent boats from Acasta and Magicienne to the wrecks. Boarding unopposed, the boat parties removed the remaining French crewmen as prisoners and set both ships on fire.[22][Note 6] Lastly, in 1847 the Admiralty awarded the surviving claimants from the action the Naval General Service Medal with clasp "St. Domingo".

On 18 August Magicienne was in company with Penguin, Franchise, and Veteran as they escorted a fleet of 109 merchantmen from Jamaica to Britain. The convoy cleared the Gulf of Florida but between 19 and 23 August they ran into a gale that did not fully abate until 25 August. Initial reports had nine vessels foundering, with the crew of some being saved;[25] later reports put the loss at 13 merchant vessels foundered and two abandoned but later salvaged. Franchise lost her fore-mast and main-top-mast but together with Penguin managed to bring 71 merchant vessels back to England. (Others arrived earlier or later, and some went to America.)[26] Magicienne, however, was so badly damaged that she had to put in at Bermuda for repairs.[27]

In December 1809, Magicienne served in the Indian Ocean. During the Mauritius campaign of 1809–1811, the French Navy captured the East Indiaman Windham in the Action of 18 November 1809 but the newly arrived Magicienne under Captain Lucius Curtis recaptured her on 29 December 1809.

Loss

In March 1810, Magicienne was part of a frigate squadron comprising Iphigenia and Leopard, later joined by Nereide and Sirius.

The summer of 1810 saw a campaign against the French Indian Ocean possessions; The Île de Bourbon (Réunion) was captured in July. In August, attention was turned to Mauritius, where the British attempted to land troops to destroy coastal batteries and signals around Grand Port; the attempt turned sour, however, when two French forty-gun frigates, Bellone and Minerve, the 18-gun corvette Victor, and two East Indiaman prizes entered the harbour and took up defensive positions at the head of the main entrance channel. The French also moved the channel markers to confuse the British approach.

In the run-up to the battle, Sirius re-captured Windham, which the French had captured a second time in the Action of 3 July 1810. On the 23 August 1810 the British squadron entered the channel at Grand Port. Sirius was the first to run aground, followed by Magicienne and Néréide. Iphigenia prudently anchored in the channel some distance from the action. The French vessels concentrated all their gunfire first against Néréide and then against Magicienne.

The battle continued without interruption all night and on the 24 August the French boarded the defenceless Néréide. Once the French flag was hoisted on what was left of the foremast of the Néréide, Magicienne and the Sirius began an intense cross fire against their enemies. Still, in the evening her crew had to abandon Magicienne, setting her on fire as they left her. Magicienne lost eight men killed and 20 wounded.[4]

The battle cost the British all four frigates, including Iphigenia and Sirius.

Notes, citations, and references

Notes

- ↑ Sibylle was the name vessel of a five-ship class of 32-gun frigates designed by Sané.

- ↑ It is not clear how the French came to have as prisoners men from Hindostan. They may have been from a tender to Hindostan or prize.

- ↑ Cerf-Volant had been launched at Nantes on 8 August 1793. She was the name ship of her two-vessel class of 12-gun brigs, her sister-ship being Papillon.[10]

- ↑ A first-class share of the money for the first Poisson Volant and two other vessels was worth £457 4s 6¼d; a first-class share for the second Poisson Volant was worth £80 18s 10½d. A fifth-class share, that of a seaman, for the first Poisson Volant and the two other vessels was worth £1 11s 5d; a fifth-class share for the second Poisson Volant was worth 3s 11½d.[12]

- ↑ This is probably Huron, of Bordeaux. Huron was probably commissioned in 1793, of 300 tons (French; of load), armed with 18 to 20 guns, with a crew of nine officers and between 112 to 180 men. She was under Captain Pierre Destebetcho in 1793 (dates not clear), Captain Harismedy circa late 1797-1798, Destebetcho (first name not clear) from July 1798 to 1799, and Captain Saint Guiron from 1799 in Bordeaux to May 1800 in Mauritius.[18]

- ↑ Penguin shared by agreement in Magicienne's prize money from the action. At the second and final distribution of prize money for the battle, a seaman on Magicienne received ₤1 19s 7d.[23] Because of the sharing arrangement, this was 14s 7d less what seamen on the other British vessels received. Magicienne and Penguin also shared in the proceeds of sundry parts and stores salvaged from the wrecked French vessels.[24]

Citations

- ↑ "No. 20939". The London Gazette. 26 January 1849. p. 241.

- ↑ "No. 12239". The London Gazette. 3 November 1781. p. 4.

- ↑ "No. 12279". The London Gazette. 16 March 1782. p. 1.

- 1 2 3 Winfield (2008), p.202.

- ↑ "No. 12381". The London Gazette. 19 October 1782. p. 1.

- ↑ "No. 15270". The London Gazette. 24 June 1800. p. 733.

- ↑ Demerliac 1792-1799, p. 226, n°1846

- ↑ "No. 13996". The London Gazette. 25 March 1797. pp. 287–288.

- ↑ Dye, pp.184-5.

- ↑ Winfield and Roberts (2015), p. 207.

- ↑ "No. 14004". The London Gazette. 25 April 1797. p. 377.

- ↑ "No. 18400". The London Gazette. 28 September 1827. p. 2015.

- ↑ "No. 15009". The London Gazette. 21 April 1798. p. 334.

- ↑ James (1837), Vol. 3, p.58.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle, Vol. 4, pp.507-8.

- ↑ The Naval Chronicle, Vol. 4, p.529.

- ↑ "No. 15333". The London Gazette. 31 January 1801. pp. 140–141.

- ↑ Demerliac (2004), №2338, p.266.

- ↑ "No. 15916". The London Gazette. 6 May 1806. p. 575.

- ↑ "No. 15909". The London Gazette. 21 April 1806. p. 464.

- ↑ Allen (1853), Vol. 2, p.156.

- ↑ Allen (1853), Vol. 2, p.161.

- ↑ "No. 16088". The London Gazette. 17 November 1807. p. 1545.

- ↑ "No. 16017". The London Gazette. 7 April 1807. p. 441.

- ↑ Lloyd's List, no. 4088.

- ↑ Naval chronicle, Vol. 16, p.341/

- ↑ Marshall (1824), Vol. 2, Part 2, pp.222-8.

References

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine de la Révolution: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1792 à 1799 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-906381-24-1.

- Demerliac, Alain (2004). La Marine du Consulat et du Premier Empire: Nomenclature des Navires Français de 1800 A 1815 (in French). Éditions Ancre. ISBN 2-903179-30-1.

- Dye, Ira (1994) The fatal cruise of the Argus: two captains in the War of 1812. (Naval Institute Press).

- Hamilton, Sir Richard Vesey, ed. (1901) The Letters and Papers of Admiral of the Fleet Sir Thomas Byam Martin, G.C.B., Vol. 3. (Naval Records Society, Vol. 19).

- James, William (1837), The Naval History of Great Britain, from the Declaration of War by France in 1793, to the Accession of George IV., 1, R. Bentley

- Marshall, John (1823–35) Royal naval biography; or, Memoirs of the services of all the flag-officers, superannuated rear-admirals, retired-captains, post-captains, and commanders, whose names appeared on the Admiralty list of sea officers at the commencement of the present year or who have since been promoted. (London: Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown).

- Winfield, Rif (2008), British Warships in the Age of Sail 1793–1817: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates, Seaforth, ISBN 1-86176-246-1

- Winfield, Rif & Stephen S Roberts (2015) French Warships in the Age of Sail 1786 - 1861: Design Construction, Careers and Fates. (Seaforth Publishing). ISBN 9781848322042