Frances Gertrude McGill

| Frances Gertrude McGill | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Frances Gertrude McGill November 18, 1882 Minnedosa, Manitoba |

| Died |

January 21, 1959 (aged 76) Winnipeg, Manitoba |

| Nationality | Canadian |

| Alma mater | University of Manitoba |

| Occupation | Bacteriologist, forensic pathologist, criminologist, allergologist |

| Known for | Pioneering the use of forensic pathology in Canadian police work |

| Relatives |

Herbert McGill (brother)

Harold McGill (brother) Margaret McGill (sister) |

Frances Gertrude McGill (November 18, 1882 – January 21, 1959) was a pioneering Canadian forensic pathologist, criminologist, allergologist, and allergist. After graduating with her medical degree from the University of Manitoba in 1915, McGill moved to Saskatchewan and became the provincial bacteriologist and then the provincial pathologist. She worked extensively with the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and local police forces for more than thirty years, conducting forensic examinations across the province, and was instrumental in establishing the first RCMP forensic laboratory. She was director of the RCMP laboratory for three years, and trained new RCMP recruits in forensic methods of detection. McGill became internationally known for her expertise in forensic pathology, and received the nickname "the Sherlock Holmes of Saskatchewan".

Alongside her pathological work, McGill also operated a private medical practice for the diagnosis and treatment of allergies. She was acknowledged as a specialist in allergy testing, and doctors across Saskatchewan referred their patients to her care.

After retiring in 1946 from her position at the RCMP laboratory, McGill was appointed Honorary Surgeon for the RCMP by the Canadian Minister of Justice, becoming one of the first official female members of the force. She continued to act as a consultant to the RCMP up until her death.

She is a member of the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame. After her death, McGill Lake in northern Saskatchewan was named in her honor.

Early life and education

Frances Gertrude McGill was born on November 18[1]:1, 1882[2][3][note 1] in Minnedosa, Manitoba.[5][6] Her parents were Edward McGill, whose family had emigrated from Ireland to Canada in 1819, and Henrietta Wigmore, also of Irish descent.[4] Henrietta was a former school teacher, and had once circumnavigated the globe while travelling between teaching jobs in Canada and New Zealand. Edward was active in local politics and agricultural societies, and worked as the Post-Master in Minnedosa.[1]:1

Frances had two older brothers, Herbert and Harold, and one younger sister named Margaret. Harold eventually became a doctor, serving as a medical officer during World War I, while Margaret became a nurse and joined the Canadian Army Medical Corps.[4]

In September 1900[1]:2, McGill's parents accidentally drank contaminated water at a county fair.[7] They became ill with typhoid fever, and both died within ten days of each other. McGill's eldest brother, Herbert, took over the running of the family farm until his younger siblings had completed their basic schooling.[4]

McGill trained as a teacher at the Winnipeg Normal School, and taught summer school for a few years in order to fund her further education.[2][5] Although she originally considered becoming a lawyer, she decided to study medicine instead.[5][8] She was able to finance much of her studies through scholarships.[4] In 1915, McGill completed her medical degree at the University of Manitoba, having received the Hutchison Gold Medal for highest academic standing[9][10], the Dean's Prize, and an award for her surgical knowledge.[8] She was one of the first female medical students to graduate from the university.[2] McGill served her internship at the Winnipeg General Hospital and subsequently attended the provincial laboratory of Manitoba for post-graduate training.[9] After observing her professor, Dr. Gordon Bell, performing autopsies for the police, McGill took a course in pathology to pursue her new interest.[1]:3

Career

Bacteriologist

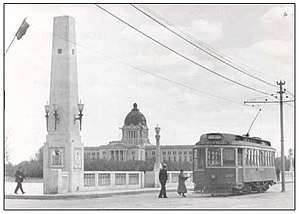

Becoming known for her work in bacteriology[5], McGill was named provincial bacteriologist for the Saskatchewan Department of Health in 1918.[9] She moved to Regina for the job, where her new office and lab were located in the Saskatchewan Legislative building. She was soon responsible for handling local outbreaks of the 1918 flu epidemic. Working quickly with her colleagues, McGill produced anti-flu vaccinations for more than 60,000 Saskatchewan residents.[1]:5-7

McGill also treated returning World War I soldiers for venereal disease.[7] Setting up clinics across the province, McGill directed her staff to conduct the newly-developed Wassermann test to detect syphilis in patients.[1]:8

Pathologist

In 1920, McGill became provincial pathologist for Saskatchewan, and two years later she became director of the provincial laboratory.[9][2] McGill now dealt with cases of suspicious death, working extensively with local police forces and the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP). Her investigations often required travelling in all sorts of weather and environments, and McGill sometimes had to use a snowmobile, dog sled or float plane to reach the necessary crime scenes.[9] In a single year, she made as many as forty-three excursions to investigate crimes, even travelling to remote northern locations in the Arctic Circle.[8]

McGill gained a reputation among law enforcement officers as a skilled and meticulous criminologist,[9] and was fondly nicknamed "Doc" by members of the police force.[7][11] Her personal motto was reportedly "Think like a man, act like a lady and work like a dog."[5] She was known for handling the sometimes gruesome nature of her work by maintaining a good sense of humour,[5] and was a formidable, no-nonsense witness in court cases.[8] During her court testimonies, McGill sometimes encountered young Saskatchewan defense lawyer John Diefenbaker – who would later become Prime Minister of Canada – and the strong-willed pair often sparred verbally. In one court hearing, McGill told Diefenbaker: "You ask me sensible questions and I will give you sensible answers".[1]:90

She was recognized by the RCMP for her "untiring" efforts and "excellent" service, and her work was acknowledged in annual reports by RCMP Commissioners James Howden MacBrien[12] and Stuart Taylor Wood.[13] McGill became well known to the Canadian public, and was called "the Sherlock Holmes of Saskatchewan".[8][3]

During the Great Depression of the 1930s, McGill used her resourcefulness to complete her work as provincial pathologist with dramatically fewer resources and a much smaller staff. In 1933, she managed to stay within a budget of $17,000 for testing work that would normally have cost more than $122,000.[1]:39

Volunteering hundreds of additional work hours on evenings and weekends, McGill assisted the RCMP in establishing their first official laboratory for forensic detection, which opened in 1937. Despite her forensic experience, she was not offered the position of director for the lab.[1]:127 The laboratory took over a substantial portion of McGill's forensic pathology workload,[14] and over the next several years she concentrated on other projects such as developing a polio serum and a growing specialization in allergy research. As her expertise in allergy testing began gaining wider notice, doctors across the province began sending their patients to McGill. She coped with the growing demands on her time by obtaining an assistant and opening a private after-hours allergy clinic located at her apartment.[1]:129-131

McGill retired from her job as provincial pathologist on November 17, 1942. She continued working at her allergy clinic two days per week, and spent more time on outdoor activities and trips with friends. Several months afterwards, McGill decided to start a new endeavor providing vaccinations for preschool children, and subsequently set up innoculation clinics at schools across Regina.[1]:136

RCMP forensic lab

In 1943, when the director of the RCMP's forensic laboratory died in an airplane accident, McGill was called in to serve as a replacement.[9][5] She accepted the position, but only on the condition that it was part-time, allowing her to continue operating her allergy clinic.[1]:138 She conducted investigations across Saskatchewan.[5]

She also provided lectures and training in pathology and toxicology to new police officers and detectives, teaching skills related to identifying blood samples, studying crime scenes, and properly collecting and preserving evidence.[9] In her advice to students, McGill emphasized the importance of critical thinking: "Don't believe all the death certificates you see. There's no reason why a man with heart disease can't have died of strychnine poisoning."[15]

.jpg)

Retirement and special consultancy

In 1946, McGill formally retired from directing the RCMP forensic laboratory. On January 16, 1946, she was named Honorary Surgeon to the RCMP, appointed by Canadian Minister of Justice Louis St. Laurent.[2][5][1]:142 She was the first woman to receive the title, and the first female doctor to be publicly acknowledged as a member of the RCMP. McGill continued to work for the RCMP on a special consulting basis, and occasionally gave lectures and exams for police officers and investigators. She was such a thorough and articulate instructor that her teaching notes were once compiled for use in a student textbook in 1952.[1]:143

Her forensic work – and her reputation as one of the few female members of the RCMP – continued to attract notice across Canada and overseas. In 1945, McGill was offered a job as pathologist at an English university, which she considered but ultimately turned down.[1]:149 A few years later, however, she travelled to England and visited Scotland Yard, where she was permitted to inspect their forensic laboratories.[6][1]:150

Cases and methodology

Whenever McGill encountered a memorable case in her forensic work, she often gave it a name.[7]

She was meticulous in her work of helping to prove a suspect's guilt or innocence. In 1933, in the case of a suspicious death in Nipawin, McGill painstakingly reconstructed the victim's skull – shattered into dozens of pieces – in order to reveal the bullet hole from a gun wound.[15][14] In the Elzie Burden Case, when a migrant worker was suspected of murder, McGill found evidence that a local youth was the true culprit.[11] In the 1934 Wilkie Case [1]:46-51, McGill gave testimony for a case in which a couple had poisoned their son with carbon monoxide.[16] When the defense lawyer for the couple accused McGill of drawing a false conclusion in the autopsy, McGill "thundered in response", providing an airtight explanation of her methods to show that carbon monoxide had caused the boy's death "without any doubt whatsoever".[7]

McGill was also skilled in uncovering the sometimes less-nefarious truth behind suspicious deaths. In the South Poplar Case, a man was found dead in below-freezing weather, his skull apparently fractured from a blow to the head. McGill's forensic investigation showed, however, that he had simply died from a heart attack. A childhood case of rickets and the after-effects of cold weather had caused the damage to the man's skull.[11] In the Lintlaw Case, when a Saskatchewan farmer was found dead from a gunshot wound, with the gun hidden nearby, the local doctor ruled it murder and the police arrested a neighbour. Unsatisfied with the lack of hard evidence, however, McGill ordered the body exhumed and did a new examination herself. From clues such as the awkward angle of the wound, she concluded that the dead man had actually taken his own life, managing to hide the weapon nearby before he died to disguise the fact that it was suicide.[11] The supposedly incriminating bloodstains on the neighbour had been animal blood from an injured farm animal.[5][8]

Her work sometimes allowed her to solve cases that nobody had known existed. During one year, McGill performed post-mortem examinations of thirteen exhumed bodies, and discovered that five of the bodies were murder victims.[15] In the Bran Muffin Case – not initially suspected as a crime at all – McGill helped prove that a woman had poisoned several relatives.[11]

Personal life

McGill never married, choosing to invest her time and efforts in a career she loved.[7] She was often private, preferring not to discuss her personal life in great detail, but many of her acquaintances believed that she had once lost a boyfriend to battle in World War I.[1]:37 McGill enjoyed spending time with her siblings and other relatives whenever possible. From 1931–33, her nephew Edward came to live with her in Regina while he built up his savings for university education, and he later cited her guidance and advice as a major influence on his life.[1]:43 McGill spent many Christmas holidays with Edward and his family, where she was popular with his children for her exciting tales of adventure.[1]:152

She enjoyed hosting meals and playing games of bridge with her close friends,[7] and she was known as a good storyteller.[1]:4 She was an avid equestrian, often going horseback riding outside the city.[7] McGill's other pastimes included fishing, camping, and shooting,[14] and in 1917 she won a prize in a women's rifle competition.[17] For bedtime reading, she often indulged in crime fiction.[1]:43 During World War II, McGill supported the war effort by knitting wool socks for soldiers who were fighting abroad.[5] She was a member of the Saskatchewan Medical Society, the Canadian College of Physicians and Surgeons,[10][18] the Business and Professional Women's Club, and the Regina Women's Canadian Club.[9]

McGill was a member of the Anglican Church.[10] She was Conservative in her politics,[11] and eventually became a strong supporter of John Diefenbaker's political career as he ran for parliament and then Prime Minister. In 1958, despite serious health struggles, McGill had herself discharged from hospital and taken home in order to place her vote for Diefenbaker in the federal election.[1]:160

She traveled extensively whenever possible, visiting New Zealand, Australia, South Africa, Mexico, the West Indies and multiple European countries.[15] She had friends and relatives in many of these countries, and often stayed with them during her travels.[1]:152

Death and legacy

After being diagnosed with breast cancer and later pleurisy,[1]:155 McGill died on January 21, 1959,[2] in Winnipeg.[5][10][18] After her cremation, her ashes were scattered by family at a favourite plot of land in Cherry Valley, Manitoba.[1]:161

McGill Lake, located in northern Saskatchewan, is named in her honour.[8][2][11] She is a member of the Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame.[19] Many of McGill's forensic detection methods are still used in modern policing around the world, or have set foundations for new forensic science.[20][8]

In 2014, McGill was among the nominees suggested for new inclusion on Canadian currency.[3]

Notes

- ↑ Although some sources alternatively cite McGill's birth year as 1877, the 1882 date is further supported by McGill's birth record (freely available for viewing online via the Manitoba Vital Statistics Agency). In addition, McGill's older brother Harold was born in 1879,[4] which makes the 1877 birthdate for Frances McGill illogical.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Petersen, Myrna (2005). The Pathological Casebook of Dr. Frances McGill, Regina: Ideation Entertainment.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 The encyclopedia of Saskatchewan. University of Regina. Canadian Plains Research Center. Regina: University of Regina, Canadian Plains Research Center. 2005. p. 584. ISBN 0889771758. OCLC 57639332.

- 1 2 3 "Saskatchewan's Frances Gertrude McGill on Canadian money? | CBC News". CBC. Retrieved 2018-05-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McGill, Harold (2007). Medicine and duty: the World War I memoir of Captain Harold W. McGill, Medical Officer, 31st Battalion, C.E.F. Norris, Marjorie, Calgarie: University of Calgary Press. pp. xiii-xx

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 "Canada's 'Sherlock Holmes of Forensic Science'". Kingston Whig-Standard. April 24, 2013. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- 1 2 "Dr. Frances McGill Honorary Member of RCMP Dies". The Ottawa Journal. January 24, 1959. p. 5. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "History Matters: Canada's first female forensic pathologist helped Mounties solve crimes". Saskatoon StarPhoenix. 2017-05-09. Retrieved 2018-05-18.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Merna., Forster, (2011). 100 more Canadian heroines : famous and forgotten faces. Toronto: Dundurn. pp. 243–245. ISBN 9781554889709. OCLC 718182176.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 "Dr. Frances Gertrude McGill". Celebrating Women's Achievements. Library and Archives Canada. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- 1 2 3 4 "Miss F. G. McGill, Medical Doctor, Police Lecturer, Dies". Winnipeg Free Press. January 22, 1959.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Carlotta., Hacker, (1974). The indomitable lady doctors. Federation of Medical Women of Canada. Toronto: Clarke, Irwin. pp. 198–205. ISBN 0772007233. OCLC 1081912.

- ↑ MacBrien, J. H. (1935). "Report of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for the year ended March 31, 1935" (PDF). Canadian Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness. p. 31.

- ↑ Wood, S. T. (1949). "Report of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police for the year ended March 31, 1949" (PDF). Canadian Department of Public Safety and Emergency Preparedness.

- 1 2 3 "Dr. Frances McGill was Saskatchewan's answer to Sherlock Holmes". Regina Leader-Post. 2017-06-19. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- 1 2 3 4 McGill, Frances; Willock, David (October 22, 1955). "She Solved Murders in the Morgue". The Winnipeg Tribune - Weekend Magazine. 5 (43). pp. 24–25, 27, 30, 39.

- ↑ Waiser, Bill (Summer 2009). "A Prairie Parable: the 1933 Bates Tragedy". Great Plains Quarterly: 203–218.

- ↑ "Wins Prize in Rifle Competition". The WInnipeg Tribune. May 9, 1917. p. 6. Retrieved 2018-05-19.

- 1 2 "Dr. Frances McGill, Crime Pathologist". The Winnipeg Evening Tribune. January 22, 1959. p. 25. Retrieved 2018-07-29.

- ↑ "The Canadian Science and Engineering Hall of Fame - Canada Science and Technology Museum". ingeniumcanada.org. Retrieved 2018-05-21.

- ↑ Johnston, David; Jenkins, Tom (2017-03-15). Ingenious: How Canadian Innovators Made the World Smaller, Smarter, Kinder, Safer, Healthier, Wealthier and Happier. McClelland & Stewart. p. 73. ISBN 9780771050916.