François Rabelais

| François Rabelais | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Between 1483 and 1494 Chinon, Kingdom of France |

| Died |

9 April 1553 Paris, Kingdom of France |

| Occupation | Writer, physician, humanist |

| Nationality | French |

| Alma mater | |

| Literary movement | Renaissance humanism |

| Notable works | Gargantua and Pantagruel |

François Rabelais (/ˌræbəˈleɪ/;[1] French: [fʁɑ̃swa ʁablɛ]; between 1483 and 1494 – 9 April 1553) was a French Renaissance writer, physician, Renaissance humanist, monk and Greek scholar. He has historically been regarded as a writer of fantasy, satire, the grotesque, bawdy jokes and songs. His best known work is Gargantua and Pantagruel. Because of his literary power and historical importance, Western literary critics consider him one of the great writers of world literature and among the creators of modern European writing.[2] His literary legacy is such that today, the word Rabelaisian has been coined as a descriptive inspired by his work and life. Merriam-Webster defines the word as describing someone or something that is "marked by gross robust humor, extravagance of caricature, or bold naturalism".[3]

Biography

No reliable documentation of the place or date of the birth of François Rabelais has survived. While some scholars put the date as early as 1483, he was probably born in November 1494 near Chinon in the province of Touraine, where his father worked as a lawyer.[4][5] The estate of La Devinière in Seuilly in the modern-day Indre-et-Loire, allegedly the writer's birthplace, houses a Rabelais museum.

Rabelais became a novice of the Franciscan order, and later a friar at Fontenay-le-Comte in Poitou, where he studied Greek and Latin as well as science, philology, and law, already becoming known and respected by the humanists of his era, including Guillaume Budé (1467-1540). Harassed due to the directions of his studies and frustrated with the Franciscan order's ban on the study of Greek (because of Erasmus' commentary on the Greek version of the Gospel of Saint Luke),[6] Rabelais petitioned Pope Clement VII (in office 1523-1534) and gained permission to leave the Franciscans and to enter the Benedictine order at Maillezais in Poitou, where he was more warmly received.[7]

Later he left the monastery to study medicine at the University of Poitiers and at the University of Montpellier. In 1532 he moved to Lyon, one of the intellectual centres of France, and in 1534 began working as a doctor at the Hôtel-Dieu de Lyon (hospital), for which he earned 40 livres a year. During his time in Lyon, he edited Latin works for the printer Sebastian Gryphius, became friends with Étienne Dolet, and worked up the nerve to write to Erasmus. Gryphius published his translations of Hippocrates, Galen and Giovanni Mainardi. As a physician, he used his spare time to write and publish humorous pamphlets critical of established authority and preoccupied with the educational and monastic mores of the time.[8]

In 1532, under the pseudonym Alcofribas Nasier (an anagram of François Rabelais), he published his first book, Pantagruel King of the Dipsodes, the first of his Gargantua series. The idea of basing an allegory on the lives of giants came to Rabelais from the folklore legend of les Grandes chroniques du grand et énorme géant Gargantua, which were sold as popular literature at the time in the form of inexpensive pamphlets by colporters and at the fairs of Lyon.[9] In this book, Rabelais sings the praises of Chinon wines through vivid descriptions of the "eat, drink and be merry" lifestyle of the main character, Pantagruel (a giant), and of his friends. This book, critical of the existing monastic and educational system, contained the first known occurrence in French of the words encyclopédie, caballe, progrès and utopie among others.[10] Despite the popularity of his book, both it and his prequel book (1534) on the life of Pantagruel's father Gargantua were condemned by the academics at the Sorbonne for their unorthodox ideas and by the Roman Catholic Church for their derision of certain religious practices.

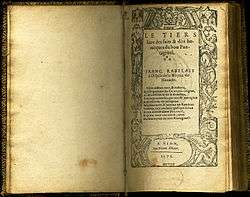

In 1537, Rabelais gave an anatomy lesson at Hôtel-Dieu on the corpse of a hanged man.[11] Rabelais's third book (Le Tiers Livre), published under his own name in 1546, was also banned. Its subject—Panurge's constant self-questioning as to whether he should marry or not— allowed Rabelais to revisit discussions he'd had while working as a secretary to Geoffrey d'Estissac earlier in Poitiers: la querelle des femmes being a lively subject in intellectual circles at the time.[12]

With support from members of the prominent du Bellay family, Rabelais received approval from King François I to continue to publish his collection. However, after the king's death in 1547, the academic élite frowned upon Rabelais, and the French Parlement suspended the sale of his fourth book (Le Quart Livre) published in 1552.[13][14]

Rabelais traveled frequently to Rome with his friend Cardinal Jean du Bellay, and lived for a short time in Turin (1540- ) as part of the household of du Bellay's brother, Guillaume, while king François I was his patron. Rabelais spent some time in hiding, under periodic threat of being condemned of heresy depending upon the health of his various protectors. Only the protection of du Bellay saved Rabelais after the condemnation of his novel by the Sorbonne.[15] Du Bellay would again help Rabelais in 1540 by seeking a papal authorization to legitimize two of his children (Auguste François, father of Jacques Rabelais, and Junie). Rabelais taught medicine at Montpellier in 1534 and in 1539.[16]

In June 1543 Rabelais became a Master of Requests.[17]

Between 1545 and 1547 François Rabelais lived in Metz, then a free imperial city and a republic, to escape the condemnation by the University of Paris. In 1547, he became curate of Saint-Christophe-du-Jambet in Maine and of Meudon near Paris, from which he resigned in January 1553 before his death in Paris in April 1553.[18]

Different accounts survive of Rabelais' death and of his last words. According to some, he wrote a famous one sentence will: "I have nothing, I owe a great deal, and the rest I leave to the poor", and his last words were "I go to seek a Great Perhaps." One "last words" reference work provides at least four distinct versions of his last words (and additional variations of these). While many accounts feature the phrase "un grand peut-être" ("a Great Perhaps") – all are listed as "doubtful" due to lack of documentation. Additionally, some sources examined for Rabelais' last words cite Cardinal du Bellay; others cite Cardinal de Chatillon, creating further confusion.[19]

Gargantua and Pantagruel

Gargantua and Pantagruel relates the adventures of two giants, Gargantua and his son Pantagruel. The tales, celebrating the spirit of "Pantagruelism", are ribald, bawdy, satirical, mock-extravagant, mock-pedantic, and lustily irreverent yet heartily devout. The Author's Prologue opens with fair warning: "Most noble boozers, and you my very esteemed and poxy friends—for to you and you alone are my writings dedicated ...".[20]:37 While the first two books focus on the lives of the two giants, the three books that follow are mainly devoted to the adventures of Pantagruel and his collection of friends—such as Panurge, a roguish, erudite maverick, and Brother Jean, a bold, voracious and boozing ex-monk—on a rambling sea-voyage in quest of the "divine Bottle".[21]

Although most chapters are humorous, wildly fantastic and frequently absurd, a few relatively serious passages have become famous for expressing humanistic ideals of the time. In particular, the chapters on Gargantua's boyhood and Gargantua's paternal letter to Pantagruel[20]:192-6 present a quite detailed vision of education.

Thélème

In the first book, Rabelais writes of the Abbey of Thélème, built by the giant Gargantua. It differs remarkably from the monastic norm, as the abbey has a swimming pool, maid service, and no clocks in sight. A verse in the inscription on the gate to the abbey reads:

- Grace, honour, praise, and light

- Are here our sole delight;

- Of them we make our song.

- Our limbs are sound and strong.

- This blessing fills us quite,

- Grace, honour, praise, and light.

- [20]:154

The Thélèmites in the abbey live according to a single rule:

All their life was regulated not by laws, statutes, or rules, but according to their free will and pleasure. They rose from bed when they pleased, and drank, ate, worked, and slept when the fancy seized them. Nobody woke them; nobody compelled them either to eat or to drink, or to do anything else whatever. So it was that Gargantua had established it. In their rules there was only one clause:

- DO WHAT YOU WILL

because people who are free, well-born, well-bred, and easy in honest company have a natural spur and instinct which drives them to virtuous deeds and deflects them from vice; and this they called honour. When these same men are depressed and enslaved by vile constraint and subjection, they use this noble quality which once impelled them freely towards virtue, to throw off and break this yoke of slavery. For we always strive after things forbidden and covet what is denied us.[20]:159

Use of language

The French Renaissance was a time of linguistic controversies. Among the issues debated by scholars was the question of the origin of language. What was the first language? Is language something that all humans are born with or something that they learn? Is there some sort of connection between words and the objects they refer to, or are words purely arbitrary? Rabelais deals with these matters, among many others, in his books.

The early 16th century was also a time of innovations and change for the French language, especially in its written form. The first book of French grammar was published in 1530, followed nine years later by the language's first dictionary. Since spelling was far less codified than it is now, each author used his own orthography. Rabelais himself developed a personal set of rather complex rules. He was a supporter of etymological spelling, i.e., one that reflects the origin of words, and was thus opposed to those who favoured a simplified spelling, one that reflects the pronunciation of words.

Rabelais' use of his native tongue was original, lively, and creative. He introduced dozens of Greek, Latin, and Italian loan-words and direct translations of Greek and Latin compound words and idioms into French. He also used many dialectal forms and invented new words and metaphors, some of which have become part of the standard language. His works are filled with sexual double-entendres, dirty jokes, and bawdy songs.

Views

Most scholars today agree that the French author wrote from a perspective of Christian humanism.[22] This has not always been the case. Abel Lefranc, in his 1922 introduction to Pantagruel, depicted Rabelais as a militant anti-Christian atheist.[23] M. A. Screech opposed this view and interpreted Rabelais as an Erasmian Christian humanist, the view that commands majority support today.[24]

Rabelais was Roman Catholic. Timothy Hampton writes that "to a degree unequaled by the case of any other writer from the European Renaissance, the reception of Rabelais's work has involved dispute, critical disagreement, and ... scholarly wrangling ..."[25] But at present, "whatever controversy still surrounds Rabelais studies can be found above all in the application of feminist theories to Rabelais criticism".[26]

In literature

| French literature |

|---|

| by category |

| French literary history |

| French writers |

|

| Portals |

|

In his novel Tristram Shandy, Laurence Sterne quotes extensively from Rabelais.[27]

Alfred Jarry performed, from memory, hymns of Rabelais at Symbolist Rachilde's Tuesday salons. Jarry worked for years on an unfinished libretto for an opera by Claude Terrasse based on Pantagruel.[28]

Anatole France lectured on him in Argentina. John Cowper Powys, D. B. Wyndham-Lewis, and Lucien Febvre (one of the founders of the French historical school Annales) wrote books about him. Mikhail Bakhtin, a Russian philosopher and critic, derived his celebrated concept of the carnivalesque and grotesque body from the world of Rabelais.[2]

Hilaire Belloc was a great admirer of Rabelais. He praised him as "at the summit" of authors of fantastic books.[29] He also wrote a short story entitled "On the Return of the Dead" in which Rabelais descended from heaven to earth in 1902 to give a lecture in praise of wine at the London School of Economics, but was instead arrested.[30]

Mikhail Bakhtin wrote Rabelais and His World, praising the author for his unbridled embrace of the carnival grotesque. In the book he analyzes Rabelais's use of the carnival grotesque throughout his writings and laments the death in modern culture of the purely communal spirit and regenerating laughter of the carnival.[2]

George Orwell was not an admirer of Rabelais. Writing in 1940, he called him "an exceptionally perverse, morbid writer, a case for psychoanalysis".[31]

Milan Kundera, in a 2007 article in The New Yorker, commented on a list of the most notable works of French literature, noting with surprise and indignation that Rabelais was placed behind Charles de Gaulle's war memoirs, and was denied the "aura of a founding figure! Yet in the eyes of nearly every great novelist of our time he is, along with Cervantes, the founder of an entire art, the art of the novel".[32]

Rabelais was a major reference point for a few main characters in Robertson Davies's novel The Rebel Angels, part of The Cornish Trilogy. One of the main characters in the novel, Maria Theotoky, attempts to write her PhD on the works of Rabelais, while a murder plot unfolds around a scholarly unscathed manuscript. Rabelais was also mentioned in Davies's books The Lyre of Orpheus, (pp 178-181), and Tempest-Tost.

Rabelais is highlighted as a pivotal figure in Kenzaburō Ōe's acceptance speech for the Nobel Prize in Literature in 1994.[33]

Henry Miller, in his first novel, Tropic of Cancer, speaks admiringly of Rabelais in several passages.

Honours, tributes and legacy

- The public university in Tours, France is named Université François Rabelais.

- Honoré de Balzac was inspired by the works of Rabelais to write Les Cent Contes Drolatiques (The Hundred Humorous Tales). Balzac also pays homage to Rabelais by quoting him in more than twenty novels and the short stories of La Comédie humaine (The Human Comedy). Michel Brix wrote of Balzac that he "is obviously a son or grandson of Rabelais... He has never hidden his admiration for the author of Gargantua that he cites in Le Cousin Pons as "the greatest mind of modern humanity".[34][35] In his story of Zéro, Conte Fantastique published in La Silhouette on 3 October 1830, Balzac even adopted Rabelais's pseudonym (Alcofribas).

- Rabelais also left a tradition at the University of Montpellier's Faculty of Medicine: no graduating medic can undergo a convocation without taking an oath under Rabelais's robe. Further tributes are paid to him in other traditions of the university, such as its faluche, a distinctive student headcap styled in his honour with four bands of colour emanating from its centre.

- Asteroid '5666 Rabelais' was named in honor of François Rabelais in 1982.[36]

- In its 26 August 2009 obituary for Sen. Edward M. Kennedy, the New York Times described the late Senator as a "Rabelaisian figure in the Senate and in life".[37]

- In Jean-Marie Gustave Le Clézio's 2008 Nobel Prize lecture, Le Clézio referred to Rabelais as "the greatest writer in the French language".

- In France the moment at a restaurant when the waiter presents the bill is still sometimes called le quart d'heure de Rabelais, in memory of a famous trick Rabelais used to get out of paying a tavern bill when he had no money.[38]

Works

- Gargantua and Pantagruel, a series of four or five books including:

- Pantagruel (1532)

- La vie très horrifique du grand Gargantua, usually called Gargantua (1534)

- Le Tiers Livre ("The third book", 1546)

- Le Quart Livre ("The fourth book", 1552)

- Le Cinquiesme Livre (a fifth book, whose attribution to Rabelais is debated)

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ "Rabelais, François". The American Heritage New Dictionary of Cultural Literacy.

- 1 2 3 Mihail Mihajlovič Bakhtin (1984). Rabelais and His World. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-253-20341-0. Retrieved 6 January 2013.

- ↑ "Rabelaisian". Merriam-Webster.

- ↑ The Rabelais Encyclopedia, p. xiii

- ↑ "Rabelais, François". The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001–07. Retrieved 27 May 2008.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xi.

- ↑ Febvre, Lucien (1982). The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century, the Religion of Rabelais. Harvard College. p. 264. ISBN 0-674-70825-3.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xiii-xv.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xiii.

- ↑ Huchon, Mireille (2003). ""Pantagruelistes et mercuriens lyonnais" in Lyon et l'illustration de la langue française à la Renaissance" (in French). ENS Éditions. p. 405.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xvii.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xix.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xx.

- ↑ Lefranc, Abel (1929). "Rabelais, la Sorbonne et le Parlement en 1552 (partie 1)". Comptes rendus des séances de l'Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres. 73: 276.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xix-xx.

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xvii.

- ↑ Marichal, Robert (1948). "Rabelais fût il Maître des Requêtes?". Bibliothèque d'Humanisme et Renaissance. 10: 169–178, at p. 169. JSTOR 20673434. (Registration required (help)).

- ↑ Boulenger, Jacques (1978). "Introduction: Vie de Rabelais" in Œuvres complètes de François Rabelais (in French). Gallimard (La Bibliothèque de la Pléiade). p. xx-xxi.

- ↑ Brahms, William B. (2010). Last Words of Notable People: Final Words of More than 3500 Noteworthy People Throughout History. Haddonfield, NJ: Reference Desk Press. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-9765325-2-1.

- 1 2 3 4 Rabelais, François (1955). The Histories of Gargantua and Pantagruel. Penguin Classics. Translated by J. M. Cohen. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- ↑ la dive Bouteille—as in être adorateur de la dive bouteille, to be over-fond of the (wine) bottle (Harrap's New Standard French and English Dictionary, 1972 edn, "dive"; according to Livre, the word dive is almost unique to Rabelais' phrase). Cohen translates as both "the Holy Bottle" (p 702) and "the divine Bottle" (p 704). Compare divus.

- ↑ Bowen 1998

- ↑ Davis, Natalie Zemon. "Beyond Babel" in Davis & Hampton, "Rabelais and His Critics". Occasional Papers Series, University of California Press.

- ↑ Screech 1979, p. 14

- ↑ Hampton, Timothy. "Language and Identities" in Davis & Hampton, "Rabelais and His Critics". Occasional Papers Series, University of California Press.

- ↑ Bruno Braunrot, "Critical Theory" entry in The Rabelais Encyclopedia. p. 45.

- ↑ Saintsbury, George (1912). Tristram Shandy. London: JM Dent. p. xx.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - ↑ Fisher, Ben (2000). The Pataphysician's Library: An Exploration of Alfred Jarry's Livres Pairs. Liverpool University Press. pp. 95–98. ISBN 9780853239260.

- ↑ Belloc, Hilaire. On Everything, E.P. Dutton and Company, 1910, p.239.

- ↑ Belloc, Hilaire. On Nothing and Kindred Subjects, Methuen and Co, 1908, pp.89-98.

- ↑ Cohen, Albert, "Review of Nailcruncher", The Collected Essays, Journalism and Letters of George Orwell, Vol. 2

- ↑ Kundera, Milan (8 January 2007). "Die Weltliteratur: European novelists and modernism". The New Yorker. Retrieved 10 November 2017.

- ↑ Ōe lecture, NobelPrize.org, 1994.

- ↑ Bibliothèque de la Pleiade, 1977, t.VII, p.587

- ↑ Michel Brix,Balzac and the Legacy of Rabelais, PUF, 2002–2005, vol. 102, p.838

- ↑ Schmadel, Lutz D.; International Astronomical Union (2003). Dictionary of minor planet names. Berlin; New York: Springer-Verlag. p. 480. ISBN 978-3-540-00238-3. Retrieved 9 September 2011.

- ↑ Broder, 26 August 2009.

- ↑ Brillat-Savarin, Anthelme, La Physiologie du Gout, Meditiation 28.

Bibliography

- Auden, W.H.; Kronenberger, Louis (1966), The Viking Book of Aphorisms, New York: Viking Press

- Bakhtin, Mihail, Tapani Laine, Paula Nieminen, and Erkki Salo. François Rabelais: Keskiajan Ja Renessanssin Nauru. Helsinki: Like, 1968.

- Bakhtin, M. M. [1941, 1965] Rabelais and His World. Trans. Hélène Iswolsky. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993

- Bodemer, Brett: "Pantagruel's Seventh Chapter:The Title as Suspect Codpiece."

- Bowen, Barbara C. (1998). Enter Rabelais, Laughing. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 0-8265-1306-9.

- Brahms, William B. (2010). Last Words of Notable People: Final Words of More than 3500 Noteworthy People Throughout History. Haddonfield, NJ: Reference Desk Press. ISBN 978-0-9765325-2-1.

- Broder, John M. Edward Kennedy, Senate Stalwart, Dies, The New York Times, 26 August 2009. Retrieved 2009-08-26.

- Del Campo, Gerald. Rabelais: The First Thelemite. The Order of Thelemic Knights.

- Dixon, J.E.G. & John L. Dawson. Concordance des Oeuvres de François Rabelais. Geneva: Librairie Droz, 1992.

- Febvre, Lucien. Gottlieb, Beatrice trans. The Problem of Unbelief in the Sixteenth Century: The Religion of Rabelais (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982).

- Langer, Ullrich, "Charity and the Singular: The Object of Love in Rabelais," in: Nominalism and Literary Discourse, ed. Hugo Keiper, Christoph Bode, and Richard Utz (Amsterdam: Rodopi, 1997), pp. 217–26.

- Lee, Jae Num. "Scatology in Continental Satirical Writings from Aristophanes to Rabelais" and "English Scatological Writings from Skelton to Pope." Swift and Scatological Satire. Albuquerque: U of New Mexico P, 1971. 7–22; 23–53.

- Screech, M.A. (1979). Rabelais. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1660-9.

External links

- Works by François Rabelais at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about François Rabelais at Internet Archive

- Works by François Rabelais at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Project Gutenberg e-text of Gargantua and Pantagruel

- Association de Bibliophiles Universels e-text of Gargantua in French

- A Dutch website about Rabelais

- Rabelais et la Renaissance, sur le Portail de la Renaissance française (French)

- François Rabelais Museum on the Internet (French)

- Henry Émile Chevalier, Rabelais and his editors, 1868 (French).