Fowelscombe

.jpg)

Fowelscombe (anciently Vowelscombe[1]) is an historic manor in the parish of Ugborough[1] in Devon, England. The large ancient manor house known as Fowelscombe House survives only as an ivy-covered "romantic ruin"[2] overgrown by trees and nettles,[3] situated 1 mile south-east of the village of Ugborough. The ruins are a Grade II listed building.[4] It is believed to be one of three possible houses on which Conan Doyle based his "Baskerville Hall" in his novel The Hound of the Baskervilles,[5] (1901–02) the others being Hayford Hall (also owned by John King (died 1861) of Fowelscombe) and Brook Manor.

Descent

Fowell

In the time of William Pole (died 1635), the manor of Fowelscombe comprised the estates of Bolterscombe, Smythescombe and Black Hall, situated in the parishes of Ugborough and North Huish.[7]

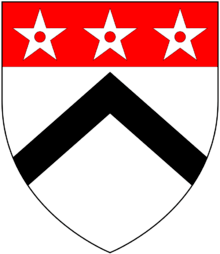

The earliest member of the Fowell (alias Foghill, Foel, etc.) family identified by William Pole (who did not record his first name) was an attorney during the reign of King Henry IV (1399–1413).[8] His eventual successor Sir Thomas Fowell (born 1453), a member of the King's court, is recorded as being born at Fowelscombe, implying that there was a house on this site before that date. His eventual successor William Fowell (died 1507)[6] of Fowelscombe was a member of parliament for Totnes in Devon in 1455.[6] His great-grandfather Thomas Fowell of Fowelscombe (who married the heiress of the Trevaige family of Cornwall) is the earliest member of the family recorded in the pedigree submitted by the family for the 1620 Heraldic visitation of Devon.[6]

The grandson of William Fowell (died 1507) was Thomas Fowell (died 1544) (son of Thomas Fowell by his wife a member of the Bevil family of Cornwall)[6] who in 1537[2] rebuilt the manor house at Fowelscombe, much of which survives today as a ruin. His great-grandson Richard Fowell (died 1594)[6] of Fowelscombe, who married Grace Somester, a daughter of John Somester of Painsford, Devon, had four sons, the younger of whom included John Fowell (1557–1627), of Plymouth, Town Clerk of Plymouth, and William Fowell (1556–1636) who founded the junior branch of the family seated at Black Hall (within the manor of Fowelscombe[7]) in the parish of North Huish. Elizabeth Fowell, a daughter of Richard Fowell (died 1594), married Sir Edward Harris (1575–1636) of Cornworthy in Devon, Chief Justice of Munster in Ireland, and a member of parliament for Clonakilty 1613–15 in the Irish House of Commons of the Parliament of Ireland. The grandson and eventual heir of Richard Fowell (died 1594) was Sir Edmund Fowell, 1st Baronet (1593–1674), of Fowelscombe, also lord of the manor of Ludbrooke in the parish of Ugborough,[9] created a baronet in 1661. In 1640 he was elected as a member of parliament for Ashburton, Devon, was a Deputy Lieutenant of Devon and during the Civil War was president of the Committee for Sequestration. He married Margaret Poulett, a daughter of Sir Anthony Poulett (1562–1600) (alias Pawlett, etc.), of Hinton St George[6] in Somerset, Governor of Jersey and Captain of the Guard to Queen Elizabeth I and a sister of John Poulett, 1st Baron Poulett (1585–1649).[8] His eldest son and heir was Sir John Fowell, 2nd Baronet (1623–1677), of Fowelscombe, who married Elizabeth Chichester (died 1678), a daughter of Sir John Chichester (1598–1669) of Hall[10] in the parish of Bishop's Tawton in Devon, Member of Parliament for Lostwithiel in Cornwall in 1624. The 2nd Baronet's son and heir was Sir John Fowell, 3rd Baronet (1665–1692), Member of Parliament for Totnes (1689–1692), who died unmarried aged 26, when the baronetcy became extinct, and was buried at Ugborough. His heirs were his two surviving sisters, who until 1711 held the Fowell estates of Fowelscombe and Ludbrooke in co-parcenary:[11]

- Elizabeth Fowell (d.post-1680), who in 1679 married (as his 1st wife) George Parker (1651–1743)[12] of Boringdon in the parish of Colebrook, and of North Molton, both in Devon. The marriage was without children, but by his second wife Anne Buller, George Parker was the grandfather of John Parker, 1st Baron Boringdon (died 1788), whose son was John Parker, 1st Earl of Morley (1772–1840) of Saltram House.

- Margaret Fowell, who in 1679 married (as his 1st wife) Arthur I Champernowne of Dartington,[13] Devon, and was the mother of Arthur II Champernowne (died 1717) of Dartington, MP for Totnes.[14]

Champernowne

In 1711 a division of the estates took place, with Fowelscombe going to the Champernowne family, which held it until 1758,[11] during the ownership of Arthur III Champernowne (died 1766),[14] of Dartington, grandson of the co-heiress Margaret Fowell.

Herbert

In 1758 Mr Herbert of Plymouth purchased the estate of Fowelscombe from the Champernowne family. The house was enlarged in the 18th century.[2] His son George Herbert of Plymouth sold it to Thomas King.[11]

King

The estate was purchased by Thomas King (died 1792)[15] from George Herbert of Plymouth. Shortly before 1808 "Mr King" (probably his brother Richard King) of Fowelscombe enclosed and improved "with great effect" 70 acres of moorland adjoining Blackdown in the parish of Loddiswell.[16] In 1810 Fowelscombe was the property and residence of his brother Richard King (died 1811),[17] who purchased Ludbrooke and the estate of Stone from Lord Boringdon. The King family made valuable agricultural improvements at Fowelscombe and other estates in Ugborough and adjoining parishes for which "the county is greatly indebted".[18] John King (died 1861)[19] of Fowelscombe, apparently formerly of Holne and Spitchwick,[20] inherited Fowelscombe in 1811[19] and was Master of the South Devon Foxhouds for two years 1827-9, when they were known as "Mr. King's Hounds", having re-established the pack, and is memorialised in the verse:[21]

When all have great merit 'twould be hard to begin,

If precedence belonged not of course to a King;

In royalty's person you seldom will find,

A good fellow and sportsman together combined;

One exception there is, for of sportsmen the best,

And a hearty good soul, is John King of the West.

It was said of John King:[22]

The late Mr. John King of Fowlescombe was an able sportsman. His hounds were rather lighter than those which meet with most consideration at the present time (1861), yet neatly proportioned and not deficient in power, and withal most true and efficient hunters. He maintained the principle that hounds should account for their fox with as little assistance as possible, and work out their own success. Naturally shrewd and observing, as dwellers and frequenters of the moor usually are, he was fully cognisant of the nature and habits of the wild animal he pursued, and when he did render assistance to his favourites it was invariably to the purpose, and followed by happy results.

In 1817 John King purchased the nearby estate of Hayford, near Buckfastleigh, then a modest farmhouse with 162 acres, and spent a large sum on transforming it into a gentleman's residence and hunting lodge, by the addition of three wings.[19] He borrowed money from Servington Savery (1787–1856) of Modbury, a solicitor and Receiver of Crown Rents, whose niece Frances Savery was married to John King's nephew Thomas King,[19][23] son of Thomas King of North Huish, who kept a small pack of harriers.[24] His ancestor was Christopher Savery (died 1623) of Shilston, Modbury, about 1 1/2 miles south-west of Fowelscombe, Mayor of Totnes in 1593 and Sheriff of Devon in 1620,[25] whose family had at some time owned Totnes Castle.[19] In 1838 Savery foreclosed on the mortgage and entered into possession of Fowelscombe and also purchased from King the estate of Hayford. He stripped Fowelscombe of its fittings, including a Jacobean staircase, wooden panelling and a turret clock made in 1810 by Samuel Northcotte of Plymouth, which clock survives today at Hayford.[19] In 1856 following a lengthy lawsuit, John King recovered possession of Fowelscombe from Savery, but was still in financial difficulties. After his death in 1861 it was sold in 1865.[19]

In 1829 John King moved to Corhampton, near Droxford, in Hampshire, (or to Cosham, near Portsmouth[19]) and was master of the Hambledon Hounds from 1829 to 1841. He suffered a serious accident in 1832, when his horse fell on him, "which interfered a good deal with his riding for some time afterwards".[26] In 1836 he was living in Hampshire and his tenant at Fowelscombe was a Mr Hosking, who looked after his hounds there. Also in 1836 the huntsman, Pinhay, "lives in Mr. King's house, at Fowlescombe, without paying rent, and his horse is kept in the stable at the kennel".[24]

According to Tozer (1916) John King died in 1841, whilst hunting with Mr. Trelawny's hounds on Dartmoor, but according to Podnieks & Chait he died in 1861. His nephew Thomas King kept a pack known as the South Devon Harriers, hunting the parishes of North Huish, Diptford and Marley.[27]

The King family were the last occupants of the manor house[28] and after their departure it fell into ruins sometime between 1860 and 1880, and is today an ivy-clad ruin.

Later history

In 1890 the estate was bought by Rev. Gordon Walters. In 1919 it was split up and sold, with the remains of Fowelscombe House being included as part of the Bolterscombe estate farm which was sold to Reginald Nicholls. Bolterscombe and the ruins of the house were sold to the Burden family in 1948.[28]

Richard Barker (1946–2015)[29] purchased the estate in 1998 and began a restoration of Bolterscombe Farm, renamed as Fowlescombe Farm.[28] As of 2018 it was an organic farm of nearly 300 acres, known as Fowlescombe.[30]

Architecture

The main building took the form of a hall house surrounded by parkland and a water garden. The 17th century stable block was built around a courtyard, which may also have been the location of the kennels for the pack of hounds used for fox and deer hunting.[28][31] The late 18th century bridge leading to the manor house is a Grade II listed building.[32]

Legend

A pack of hounds was kept at kennels at Fowelscombe for many years. It is said that a kennel-master used sometimes to keep the hounds hungry so that they would hunt well the following day, but that one night, when visiting his hounds which were making a noise, he failed to wear his usual jacket, and was eaten by the hounds, with only his boots being found the next morning.[31]

References

- 1 2 Risdon, p.179

- 1 2 3 Hoskins, W.G., A New Survey of England: Devon, London, 1959 (first published 1954), p.509

- ↑ Pevsner, Nikolaus & Cherry, Bridget, The Buildings of England: Devon, London, 2004, p.451

- ↑ "Ruins of Fowlecombe House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 16 April 2017.

- ↑ Weller, Philip, The Hound of the Baskervilles – Hunting the Dartmoor Legend, Devon Books, Halsgrove Publishing, c.2002, quoted in Dartmoor: In the footprints of a gigantic hound, The Telegraph, 9 March 2002

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Vivian, p.369

- 1 2 Pole, p.315

- 1 2 Pole, p.316

- ↑ Risdon, pp.385, 179

- ↑ Vivian, p.177, pedigree of Chichester

- 1 2 3 Risdon, p.385

- ↑ Vivian, p.370; p.588, pedigree of Parker

- ↑ Vivian, p.370

- 1 2 Vivian, p.164, pedigree of Champernowne

- ↑ Will proved 1792

- ↑ Vancouver, Charles, General View of the Agriculture of the County of Devon, London, 1808, p.135

- ↑ Will proved 1811

- ↑ Risdon, 1810 Additions, p.385

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Elizabeth Podnieks, Sandra Chait, (eds.) Hayford Hall: Hangovers, Erotics, and Modernist Aesthetics, Southern Illinois University, 2005, pp.22–4

- ↑ Tozer

- ↑ Tozer, pp.33–40

- ↑ Tozer, p.35

- ↑ Vivian, p.672, pedigree of Savery

- 1 2 Locke, John, The Game Laws, Comprising All the Acts Now in Force on the Subject..., London, 1840, pp.171–2

- ↑ Vivian, p.670, pedigree of Savery

- ↑ Tozer, p.39

- ↑ Tozer, p.40

- 1 2 3 4 Gray, Abigail (2009). "Fowlescombe Archaeological Notes" (PDF). Devon Rural Archive. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2017-02-06. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "Memorial to Richard Barker, 1946 – 2015."

- ↑ "Welcome to Fowlescombe". Fowlescombe. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 "Hounds of Fowescombe". Fowlescombe: History. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- ↑ "Bridge 100 metres south-east of Ruins of Fowelscombe House". National Heritage List for England. Historic England. Retrieved 14 August 2016.

- Sources

- Pole, Sir William (died 1635), Collections Towards a Description of the County of Devon, Sir John-William de la Pole (ed.), London, 1791.

- Risdon, Tristram (died 1640), Survey of Devon. With considerable additions. London, 1811.

- Tozer, Edward J.F., The South Devon Hunt : a history of the hunt from its foundation, covering a period of over a hundred years, with incidental reference to neighboring packs, Teignmouth, 1916, pp. 33–40

- Vivian, Lt.Col. J.L., (Ed.) The Visitations of the County of Devon: Comprising the Heralds' Visitations of 1531, 1564 & 1620. Exeter, 1895.

Further reading

- Lauder, Rosemary (1997). Vanished Houses of South Devon, Bideford: North Devon Books. pp. 115–127. ISBN 0-9528645-9-2

- Meller, Hugh (2015). The Country Houses of Devon. I. Crediton: Black Dog Press. pp. 418–420. ISBN 978-0-9524341-4-6.