Feminist businesses

Feminist businesses are companies established by activists involved in the feminist movement.[1] Examples include feminist bookstores, feminist credit unions, feminist presses, feminist mail-order catalogs, and feminist restaurants.[1][2] These businesses flourished as part of the second and third-waves of feminism in the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s.[3] Feminist entrepreneurs established organizations such as the Feminist Economic Alliance to advance their cause.[3] Feminist entrepreneurs sought three primary goals: to disseminate their ideology through their businesses, to create public spaces for women and feminists, and to create jobs for women so that they didn't have to depend on men financially.[4][2] While they still exist today, the number of some feminist businesses, particularly women's bookstores, has declined precipitously since 2000.[1][4][2][3]

Feminist Bookstores

.jpg)

Feminist bookstores hold a part of the second-wave feminism movement inside their stores, with expansion of the bookstores beginning in the 1980s.[5] In 1983 there were around 100 bookstores located in North America, which created over $400 million in sales annually.[5] There are still 13 feminist-run bookstores in the world today.[2] There is only one in Canada and the rest are spread throughout the United States, with the oldest bookstore, Antigone Books, in Tucson, Arizona.[2] The 13 book stores host feminist events to support feminism as well as carry books about the topics of queer theories, animal rights, lesbian fiction, gay studies, and also information about different cultures.[2]

The decline in feminist bookstores is due to the competition of E-Books, corporate chains, online stores, and the presence of Amazon.[6] These competitors make independent bookstores face financial difficulties.[6] Recent studies show that consumers still want both the hard copy and digital copy.[6] Besides big corporations coming in and taking business, it was also hard for feminist bookstores to keep up with the competitions distribution, publishing, as well as the ability to sell books to a wider audience.[6]

Notable stores include Amazon Bookstore Cooperative and Silver Moon Bookshop.

Feminist Economic Alliance

During the Thanksgiving of 1975, the founding women of the Feminist Economic Alliance (FEA) met in Detroit, Michigan at a conference to discuss the problems women faced with money.[7] Two leading women for the alliance in 1975 were Susan Osborne and Linda Maslanko, both from New York.[7] They were the spokeswomen for FEA and educated the public on what the alliance meant and what the future of FEA looked like after splitting into eight geographic regions.[7] The Feminist Economic Alliance was created to aid new sister credit unions as well as allowing any women to become economically powerful, independent, or grow as an individual.[7] This independence for women was going to be achieved by encouraging, assisting, and promoting the women of feminist credit unions and feminist enterprises.[7] The main idea behind this new alliance was that older sister credit unions could help the new developing credit unions by sharing research, resources, and guidance in the process.[7]

Feminist Credit Unions

In the 1970s during the second wave feminist movement, women had the urge to fight unequal credit so they created their own non-profit, financial institutions so that men were no longer in control of their money.[8] The co-manager of the union, Susan Osborne, was creating an environment for women to save money as well as help other women in need.[8] By creating their own credit unions, women were able to avoid being discriminated based on their gender even though the Equal Credit Opportunity Act of 1974 banned credit unions from discriminating potential customers.[9] The women being excluded from receiving loans despite the law in place, were divorced women, low-income women, women needing legal money or women on welfare.[8] Establishing feminist credit unions meant that they would now be able to receive loans hassle free, save their money, and gain money management counseling.[10] When receiving credit, women are viewed by their individual character rather than if they were married or single.[10] A woman no longer has to be the co-signer, she can now be in control of her money.[10] The unions run no differently than any other union, in fact, the feminist credit unions are governed by the same laws as the normal credit unions.[10]

Detroit, Michigan branch

In 1982, the Detroit, Michigan branch, the last feminist credit union, was dissolved due to financial problems and also the reconstruction of the unions language change.[11] The language was suggested to be changed to include both genders, not just female.[11] The Michigan Credit Union League saw the feminist credit unions as bias towards men and suggestions of equal consideration for males in a female position were to be given resulting in it being dissovled.[11]

Feminist Mail-Order Magazines

History

The feminist mail-order magazine came from Great Britain around the 1970s and lasted until the 1990s.[12] The collectives were notable for allowing women to take equal parts in the creation of the magazine in all areas including: copy typing, design, layout or interviewing.[12] By allowing women the equal chance at learning, women were developing their creativity and gaining new skills.[12] Women were allowed to fight back at the patriarchal system by voicing their opinions and allowing women who were excluded also have a platform.[12] Excluded women during that time were black, lesbian, working class, or single mothers.[12] Popular magazines at the time were Spare Rib, Scarlet Woman, Catcall, and Outwrite.[12] The magazines were not afraid to comment about inequalities the women were facing or issues that needed to be addressed.[13] Feminist activities were also talked about in the magazines creating networks, reformation, expressing opinions or attitudes relating to a certain topic.[13] Mail-order magazines were a way for women to become educated on feminism and how to join the movement.[13]

Magazines

Spare Rib

Spare Rib ran from 1972–93 and was an active part in the Women's Liberation movement.[14] The magazine covered issues regarding stereotypes women face as well as issues women face in the world and realistic solutions to the problems.[14]

Scarlet Woman

In April 1975, the first issue of Scarlet Woman was published by Sydney SW Collective.[15] The magazine was created to be a socialist feminist magazine and included articles dealing with money, lesbians, health and more.[15]

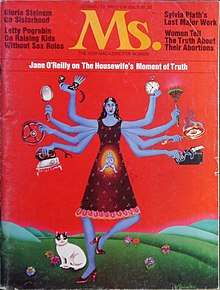

Ms. Magazine

In 1972, Gloria Steinem created the first magazine that was specifically for women, created by an entire team of women in New York.[16] Ms. Magazine was the first magazine to address domestic violence, speak about politics, or discuss topics men thought were unnatural for women, motivating the feminist movement.[17] Gloria Steinem was also the co-founder of Woman's Action Alliance and National Women's Political Caucus.[17] Brenda Feigen, co-founder of the Woman's Action Alliance with Steinem, was an attorney activist who helped Steinem brainstorm ideas for the magazine as well as held meetings in her apartment.[17] Today, Ms. Magazine is published by Liberty Media for Women, LLC, owned by Feminist Majority Foundation, that is based in Arlington, Virginia and Los Angeles, California.[18]

Feminist Restaurants

The earliest form of feminist restaurants took shape in suffrage restaurants, tea rooms, or lunch rooms.[19] Food was sold at a low cost of five or ten cents and men were permitted to eat, in hopes of women persuading men to support a certain political cause.[19] These restaurants suffered from conflicts dealing with the founders and donators.[19] Alva Belmont, a wealthy socialite, was the founder of a suffrage restaurant that was known for strict rules and a fast pace.[19] The ideas and motives behind these suffrage restaurants in the 1910s were the foundations for the feminist restaurants in the 1970s.[19]

In April 1972, the first feminist restaurant, Mother Courage, was founded by Dolores Alexander in New York.[19] Feminist restaurants are used more as a place to gather and socialize rather than eating.[19] The restaurants were used to share ideas, literature, educate one another and to promote the feminist movement.[19] Guest speakers, political speakers, poets, or musicians would come to the restaurants to promote issues or spread awareness.[20] Coffee houses and cafes are also popular among the feminist movement.[20] Restaurants offered same pay to every staff member, which was entirely women.[19] The style was simple and supported the movements that were occurring during that time.[19] They support other occupations by avoiding certain products such as lettuce and grapes for the farmers or boycotting orange juice for the anti-gay campaign.[19] Feminist restaurants were also notable for treating women or lesbians with respect in a non-hostile environment.[19] A women who is dining with a man will be given a wine sample as well as the check at the end of the meal.[19] That was typical not the case in restaurants that were not catered to feminism.[19]

Feminist Businesses Today

In today's society, feminist businesses look different besides the few bookstores left in the world.[2] There are over hundreds of companies created by women, that have a purpose besides making money such as changing our society, impacting employers and the consumers they reach.[21] One famous company started by a woman that has been successful is Tory Burch.[21] She created the store from nothing and has been able to create a multibillion-dollar business as well as a foundation called the Tory Burch Foundation in 2009, to help empower women and female entrepreneurs.[21] Today feminist business are about empowering women in the shape of products sold, campaigns run, and businesses created.[22][21]

References

- 1 2 3 Echols, Alice (1989). Daring to be Bad: Radical Feminism in America, 1967-1975. University of Minnesota Press. pp. 269–278, 357, 405–406. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Hogan, Kristen (2016). The Feminist Bookstore Movement: Lesbian Antiracism and Feminist Accountability. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press.

- 1 2 3 Enke, Anne (2007). Finding the Movement: Sexuality, Contested Space, and Feminist Activism. Durham, North Carolina: Duke University Press. pp. 1–104.

- 1 2 Davis, Joshua (2017). From Head Shops to Whole Foods: The Rise and Fall of Activist Entrepreneurs. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 129–175. External link in

|title=(help) - 1 2 "Business Feminism - Los Angeles Review of Books". Los Angeles Review of Books. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 "Brick and Mortar: Lessons About the Future of Bookselling | Harvard Political Review". harvardpolitics.com. Retrieved 2018-04-04.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Feminist Economic Alliance Formed to Aid New Sister Credit Unions". Duke Digital Collections. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 Knight, Michael (1974-08-27). "Feminists Open Own Credit Union". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- ↑ "Abstract: Financial Feminism: Credit Unions in the Women's Movement of the 1970s | The Business History Conference". www.thebhc.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sarasota Journal - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 "Forty-Four Years Ago a Female-Run Credit Union Paved the Way for Women's Financial Independence". Michigan Credit Union League. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Feminist collectives". The British Library. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 Forster, Laurel (2015-02-26). Magazine Movements: Women's Culture, Feminisms and Media Form. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. ISBN 9781441172631.

- 1 2 "Spare Rib". The British Library. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 http://www.vwllfa.org.au/bios-pdf/arch91-SW.pdf

- ↑ MAKERS. "MAKING HISTORY: Gloria Steinem Creates Ms. Magazine". MAKERS. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- 1 2 3 "How Do You Spell Ms". NYMag.com. Retrieved 2018-04-16.

- ↑ "Ms. Magazine Online". www.msmagazine.com. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Women's restaurants". Restaurant-ing through history. 2013-06-18. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 "The Feminist Restaurant Project". www.thefeministrestaurantproject.com. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

- 1 2 3 4 "22 successful women-led companies that prove there's much more to business than profits". Business Insider. Retrieved 2018-04-23.

- ↑ Shah, Ameera (2017-08-18). "Redefining Modern Feminism in the World of Business". Entrepreneur. Retrieved 2018-04-24.