Female hysteria

| Female hysteria | |

|---|---|

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Psychiatry |

Female hysteria was once a common medical diagnosis for women. It is no longer recognized by medical authorities as a medical disorder, but still has lasting social implications. Its diagnosis and treatment were routine for hundreds of years in Western Europe.[1] In Western medicine hysteria was considered both common and chronic among women. The American Psychiatric Association dropped the term hysteria in 1952. Even though it was categorized as a disease, hysteria's symptoms were synonymous with normal functioning female sexuality.[1] Women considered to have it exhibited a wide array of symptoms, including faintness, nervousness, sexual desire, insomnia, fluid retention, heaviness in the abdomen, shortness of breath, irritability, loss of appetite for food or sex, and a "tendency to cause trouble".[1]

In extreme cases, the woman may have been forced to enter an insane asylum or to have undergone surgical hysterectomy.[2]

Early history

The history of hysteria can be traced to ancient times. Dating back to 1900 BC in Ancient Egypt, the first descriptions of hysteria within the female body were found recorded on the Kahun Papyri.[3] In ancient Greece, it was described in the gynecological treatises of the Hippocratic Corpus, which dates back to the 5th and 4th centuries BC. Plato's dialogue Timaeus compares a woman's uterus to a living creature that wanders throughout a woman's body, "blocking passages, obstructing breathing, and causing disease".[4] The concept of a pathological wandering womb was later viewed as the source of the term hysteria,[4] which stems from the Greek cognate of uterus, ὑστέρα (hystera).

Another cause was thought to be the retention of a supposed female semen, thought to have mingled with male semen during intercourse. The female semen was believed to have been stored in the womb. Hysteria was referred to as "the widow's disease", because the female semen was believed to turn venomous if not released through regular climax or intercourse.[5] If the patient was married, this could be completed by intercourse with their spouse. Other than participating in sexual intercourse, it was thought that women could position the uterus back into place with fumigation of both the face and genitals. Fumigating the body with special fragrances would supposedly place the uterus into its natural spot in the female body.[3]

17th century

Up to and during the 17th century, people who showed signs of hysteria were categorized as being mentally ill.[6] People suffering from hysteria and other forms of mental illness were thought to be possessed by demons. After this time period, the correlation of demonic possession and hysteria were gradually discarded and instead was described as behavioral deviance, a medical issue.

18th century

In the 18th century, hysteria slowly became associated with mechanisms in the brain rather than the uterus. French physician Philippe Pinel freed hysteria patients detained in Paris’ Salpêtrière sanatorium on the basis that kindness and sensitivity are needed to formulate good care.

19th century

Jean-Martin Charcot argued that hysteria derives from a neurological disorder and showed hysteria is more common among men than women. [3]

George Beard, a physician who cataloged an incomplete list including 75 pages of possible symptoms of hysteria,[7] claimed that almost any ailment could fit the diagnosis. Physicians thought that the stress associated with the typical female life at the time caused civilized women to be both more susceptible to nervous disorders and to develop faulty reproductive tracts.[8] One American physician expressed pleasure in the fact that the country was "catching up" to Europe in the prevalence of hysteria.[7]

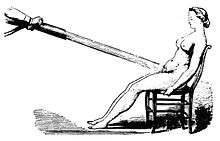

Rachel Maines hypothesized that doctors from the classical era up until the early 20th century commonly treated hysteria by masturbating female patients to orgasm (termed "hysterical paroxysm"), and that the inconvenience of this may have driven the early development of and the market for the vibrator.[1] Although Maines's theory that hysteria was treated by masturbating female patients to orgasm is widely repeated in the literature on female anatomy and sexuality,[9] some historians dispute Maines's claims about the prevalence of this treatment for hysteria and about its relevance to the invention of the vibrator, describing them as a distortion of the evidence or that it was only relevant to an extremely narrow group.[10][11][12] Maines has said that her theory should be treated as a hypothesis rather than a fact.[9]

Frederick Hollick was a firm believer that a main cause of hysteria was licentiousness present in women.[13]

Decline

During the early 20th century, the number of women diagnosed with female hysteria sharply declined. This decline has been attributed to many factors. Some medical authors claim that the decline was due to gaining a greater understanding of the psychology behind conversion disorders such as hysteria.[14]

With so many possible symptoms, historically hysteria was considered a catchall diagnosis where any unidentifiable ailment could be assigned.[3] As diagnostic techniques improved, the number of ambiguous cases that might have been attributed to hysteria declined. For instance, before the introduction of electroencephalography, epilepsy was frequently confused with hysteria.[15] Many cases that had previously been labeled hysteria were reclassified by Sigmund Freud as anxiety neuroses.[15] Sigmund Freud was fascinated by cases of hysteria. He thought that hysteria may have been related to the unconscious mind and separate from the conscious mind or the ego.[16] He was convinced that deep conflicts in the mind, some concerning instinctual drives for sex and aggression, were driving the behavior of those with hysteria. Freud developed psychoanalysis in order to help patients that had been diagnosed with hysteria reduce internal conflicts causing physical and emotional suffering. As a result, theories relating to hysteria came from pure speculation. Doctors and physicians could not connect symptoms to the disorder, causing it to decline rapidly.[17]

Today, female hysteria is no longer a recognized illness, but different manifestations of hysteria are recognized in other conditions such as schizophrenia, borderline personality disorder, conversion disorder, and anxiety attacks.[18]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 Maines, Rachel P. (1998). The Technology of Orgasm: "Hysteria", the Vibrator, and Women's Sexual Satisfaction. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-6646-4.

- ↑ Mankiller, Wilma P. (1998). The Reader's Companion to U.S. Women's History. Boston, MA: Houghton Mifflin Co. p. 26. ISBN 0-6180-0182-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Tasca C, Rapetti M, Carta MG, Fadda B (2012). "Women and hysteria in the history of mental health". Clinical Practice and Epidemiology in Mental Health. 8: 110–9. doi:10.2174/1745017901208010110. PMC 3480686. PMID 23115576.

- 1 2 King, Helen (1993). "Once upon a text: Hysteria from Hippocrates". In Gilman, Sander; King; Porter, Helen; Rousseau, G.S.; Showalter, Elaine. Hysteria beyond Freud. University of California Press. pp. 3–90. ISBN 0-520-08064-5.

- ↑ Roach, Mary (2009). Bonk: The Curious Coupling of Science and Sex. New York: W.W. Norton & Co. p. 214. ISBN 9780393334791.

- ↑ Spanos, Gottlieb, Nicholas, Jack (1979). "Demonic possession, mesmerism, and hysteria: A social psychological perspective on their historical interrelations". Journal of Abnormal Psychology: 527–546.

- 1 2 Briggs L (2000). "The race of hysteria: "overcivilization" and the "savage" woman in late nineteenth-century obstetrics and gynecology". American Quarterly. 52 (2): 246–73. doi:10.1353/aq.2000.0013. PMID 16858900.

- ↑ Morantz RM, Zschoche S (December 1980). "Professionalism, feminism, and gender roles: a comparative study of nineteenth-century medical therapeutics". Journal of American History. 67 (3): 568–88. doi:10.2307/1889868. JSTOR 1889868. PMID 11614687.

- 1 2 Maines, Rachel. "Big Think Interview with Rachel Maines". bigthink.com. Retrieved 16 November 2016.

- ↑ King, Helen (2011). "Galen and the Widow: Towards a history of therapeutic masturbation in ancient gynaecology" (PDF). EuGeStA: Journal on Gender Studies in Antiquity. 1: 205–235.

- ↑ Hall, Lesley. "Doctors masturbating women as a cure for hysteria/'Victorian vibrators'". lesleyahall.net. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Riddell, Fern (10 November 2014). "No, no, no! Victorians didn't invent the vibrator". The Guardian. Retrieved 29 October 2016.

- ↑ Hollick, Frederick (1853). The diseases of woman: their causes and cure familiarly explained ; with practical hints for their prevention and for the preservation of female health.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - 1 2 Micale MS (September 1993). "On the "disappearance" of hysteria. A study in the clinical deconstruction of a diagnosis". Isis; An International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 84 (3): 496–526. doi:10.1086/356549. PMID 8282518.

- 1 2 Micale MS (July 2000). "The decline of hysteria". The Harvard Mental Health Letter. 17 (1): 4–6. PMID 10877868.

- ↑ Coon, Mitterer, Dennis, John (2013). Introduction to Psychology: Gateways to Mind and Behavior. Cengage Learning. pp. 512–513.

- ↑ Micale MS (1993). "On the "disappearance" of hysteria. A study in the clinical deconstruction of a diagnosis". Isis; an International Review Devoted to the History of Science and Its Cultural Influences. 84 (3): 496–526. doi:10.1086/356549. JSTOR 235644. PMID 8282518.

- ↑ Costa, Dayse Santos; Lang, Charles Elias (2016). "Hysteria Today, Why?". Psicologia USP. 27 (1): 115–124 – via SciELO.

Further reading

- Libbrecht, Katrien (1995). Hysterical Psychosis: A Historical Survey. London: Transaction Publishers. ISBN 1-56000-181-X.

- Micale, Mark S. (1995). Approaching Hysteria: Disease and its Interpretations. Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03717-5.

- Micale, Mark S. (2009-06-30). Hysterical Men: The Hidden History of Male Nervous Illness. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674040984.

- Micklem, Niel (1996). The Nature of Hysteria. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-12186-8.

- Bronfen, Elisabeth (2014-07-14). The Knotted Subject: Hysteria and Its Discontents. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9781400864737.

- Augsburg, Tanya (1996). Private Theatres Onstage (Hysteria and the Female Medical Subject). UMI.

- Showalter, Elaine (1987). The Female Malady: Women, Madness and English Culture, 1830-1980. Virago. ISBN 978-0860688693.

External links

- Erika Kinetz, "Is Hysteria Real? Brain Images Say Yes" (The New York Times)

- Female Hysteria during Victorian Era