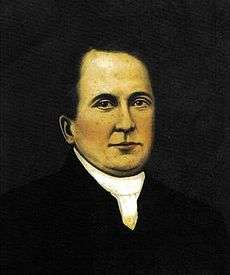

John Murphy (priest)

| John Murphy | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

1753 Tincurry, Co. Wexford |

| Died |

2 July 1798 (aged 44–45) Tullow, County Carlow |

| Nationality | Irish |

| Occupation | Catholic priest |

John Murphy (1753 – c. 2 July 1798) was an Irish Roman Catholic priest and one of the leaders of the Irish Rebellion of 1798 in Wexford who was executed by British soldiers.

Before the rebellion

He was born at Tincurry in the Parish of Ferns, County Wexford in 1753, the youngest son of Thomas and Johanna Murphy. Studying for the priesthood was then illegal in Ireland and so priests were trained abroad. Murphy sailed for Spain in early 1772 and studied for the priesthood in Seville, Spain where many of the clergy in Ireland received their education due to the persecution of Catholics.

Start of the rebellion

Fr Murphy was initially against rebellion and actively encouraged his parishioners to give up their arms and sign an oath of allegiance to the British Crown. On 26 May 1798, a company of men armed with pikes and firearms[1] gathered under Fr Murphy to decide what to do for safety against the regular yeomanry patrols at a townland called the Harrow. At about eight o'clock that evening, a patrol of some twenty Camolin cavalry spotted the group and approached them, demanding to know their business. They left after a brief confrontation, having burned the cabin of a missing suspected rebel whom they had been tasked to arrest. As the patrol returned they passed by Fr Murphy's group, who were by now angry at the sight of the burning cabin. As the cavalry passed by the men an argument developed, followed by stones being thrown and then an all-out fight between the men and the troops. Most of the cavalry quickly fled, but two of the yeomen, one of these the lieutenant in command, Thomas Bookey, were killed. The Wexford Rebellion had begun and Fr Murphy acted quickly; he sent word around the county that the rebellion had started and organised raids for arms on loyalist strongholds.

Parties of mounted yeomen responded by killing suspects and burning homes, causing a wave of panic. The countryside was soon filled with masses of people fleeing the terror and heading for high ground for safety in numbers. On the morning of 28 May, a crowd of some 3,000 gathered on Kilthomas Hill but was attacked and put to flight by Crown forces who killed 150.[2]:91 At Oulart Hill, a crowd of over 4,000 combatants had gathered,[2]:92–93 plus many women and children. Spotting an approaching North Cork Militia party of 110 rank and file, Fr Murphy and the other local United Irishmen leaders such as Edward Roche, Morgan Byrne, Thomas Donovan, George Sparks and Fr Michael Murphy organised their forces and massacred all but five of the heavily outnumbered detachment.[2]:93

The victory was followed by a successful assault on the weak garrison of Enniscorthy, which swelled the Irish rebel forces and their weapon supply. However defeats at New Ross, Arklow, and Newtownbarry meant a loss of men and weapons. Fr John Murphy had returned to the headquarters of the rebellion at Vinegar Hill before the Battle of Arklow and was attempting to reinforce its defences. 20,000 British troops arrived at Wexford with artillery and defeated the rebel, armed only with pikes (in the Battle of New Ross one man was armed with a Bronze Age sword)[3] at the Battle of Vinegar Hill on 21 June. However, due to a lack of coordination among the British columns, the bulk of the rebel army escaped to fight on.

Death

Eluding the crown forces by passing through the Scullogue Gap, Fr John Murphy and other leaders tried to spread the rebellion across the country by marching into Kilkenny and towards the midlands. On 26 June 1798 at the Battle of Kilcumney Hill in County Carlow, their forces were tricked and defeated. Fr Murphy and his bodyguard, James Gallagher, became separated from the main surviving group (fragments of which fought for six more years from the Killoughrim woods near Enniscorthy (James Corocoran) and from Wicklow mountains). Fr Murphy decided to head for the safety of a friend's house in Tullow, County Carlow, when the path cleared. They were sheltered by friends and strangers – one Protestant woman, asked by searching yeomen if any strangers had passed, answered "No strangers passed here today"; when she was later questioned about why she had not said Murphy and Gallagher had not passed, she explained that they had not – because they were still in her house when she was questioned.

After a few days, some yeomen captured Murphy and Gallagher in a farmyard on 2 July 1798. They were brought to Tullow later that day where they were brought before a military tribunal, charged with committing treason against the British crown, and sentenced to death. Both men were tortured in an attempt to extract more information from them. Fr Murphy was stripped, flogged, hanged, decapitated, his corpse burnt in a barrel of tar and his head impaled on a spike. This final gesture was meant to be a warning to all others who fought against the British Crown.

Legacy

Fr Murphy is one of the best known of the 1798 leaders and of the many Irish martyrs who died for the cause of Irish freedom. Father John proved an unlikely competent military mind as shown on numerous occasions, such as at Oulart, where he ordered his men to place their hats upon their pikes and raise them above cover to draw British gunfire, then attacked the government forces while they reloaded. When besieging towns he used the ancient technique of the cattle stampede, in which the rebels harassed and drove herds of cattle into the town, creating cover and confusion during which the rebels poured in, sheltered by the beasts. He is commemorated in the ballad Boolavogue, written in 1898 to commemorate the rebellion. Father Murphy's remains are buried in the old Catholic graveyard with Fr Ned Redmond in Ferns, Co Wexford.

Cultural depictions

In the 2015 American musical Guns of Ireland Murphy is shown taking command of the Wexford rebels up to his eventual execution. He is also shown conducting a marriage ceremony in a stylized account of the wedding after the Easter Rising of doomed leader Joseph Plunkett and Grace Gifford.[4]

References

- ↑ The 1798 Rebellion Chapter 9 of "The Last County", County Wicklow Heritage Project, 2016. Accessed 5 May 2017

- 1 2 3 Maxwell, W. H. History of the Irish Rebellion in 1798. HH Bohn, London 1854, pp 92-93, at archive.org

- ↑ https://www.independent.ie/regionals/goreyguardian/news/ancient-sword-shines-in-ottawa-museum-36544180.html

- ↑

Sources

- Hade, Mary; Moonan GG A Short History of the People of Ireland, p 432-436. ISBN 9780765605429

- Curtis E. "A History of Ireland," p 342-344

- Altholz, Josef L. "Selected Documents in Irish History". Routledge, 2000

- Keogh, Dáire; Furlong, Nicholas, eds. "The 1798 Rebellion in Wexford". Four Courts Press (1996)