Farr-e Kiyani (Faravahar)

| Part of a series on |

| Zoroastrianism |

|---|

Atar (fire), a primary symbol of Zoroastrianism |

| Primary topics |

| Angels and demons |

| Scripture and worship |

| Accounts and legends |

| History and culture |

| Adherents |

|

|

The Faravahar (Persian: فروهر), also known as Farr-e Kiyani (فر کیانی), is one of the best-known symbols of Iran. It symbolizes Zoroastrianism, the first religion of Iran before Arab invasion of Iran Persia, and Iranian nationalism.[1][2]

The Faravahar is the most worn pendant among Iranians and has become a secular national symbol, rather than a religious symbol. It symbolizes nice thoughts (پندار نیک pendār-e nik), nice words (گفتار نیک goftār-e nik) and nice deeds (کردار نیک kerdār-e nik), which are the basic tenets and principles of Zoroastrianism.

Etymology

The New Persian word فروهر is read as forouhar or faravahar (it was pronounced as furōhar in Classical Persian). The Middle Persian forms were frawahr (Book Pahlavi: plwʾhl, Manichaean: prwhr), frōhar (recorded in Pazend as 𐬟𐬭𐬋𐬵𐬀𐬭; it is a later form of the previous form), and fraward (Book Pahlavi: plwlt', Manichaean: frwrd), which was directly from Old Persian *fravarti-.[3][4] The Avestan language form was fravaṣ̌i (𐬟𐬭𐬀𐬎𐬎𐬀𐬴𐬌).

In Iranian culture

Even after the Arab conquest of Iran, Zoroastrianism continued to be part of Iranian culture. Throughout the year, festivities are celebrated such as the Iranian New Year or Nowruz, Mehregan, and Chaharshanbe Suri. These are remnants of Zoroastrian traditions. From the start of the 20th century, the Farvahar icon found itself in public places and became a known icon amongst all Iranians.

The Shahnameh by Ferdowsi is Iran's national epic and contains stories (partly historical and partly mythical) from pre-Islamic Zoroastrian times. The tomb of Ferdowsi (built early 1930), which is visited by numerous Iranians every year, contains the Faravahar icon as well.

The Sun Throne, the imperial seat of Persia, has strong relations from the Farahavar. The sovereign would be seated in the middle of the throne, which is shaped like a platform or bed that is raised from the ground. This religious-cultural symbol was adapted by the Pahlavi dynasty to represent the Iranian nation. In present-day Zoroastrianism, the Faravahar is said to be a reminder of one's purpose in life, which is to live in such a way that the soul progresses towards frashokereti, or union with Ahura Mazda, the supreme divinity in Zoroastrianism. Although there are a number of interpretations of the individual elements of the symbol, none of them are older than the 20th century.

After the Islamic Revolution of 1979, the Lion and Sun, which was part of Iran's original national flag, was banned by the government from public places in order to prevent people from being reminded of life prior to the revolution. Nevertheless, Faravahar icons were not removed. As a result, the Faravahar icon became a national symbol amongst the people, and it became somewhat tolerated by the government as opposed to the Lion and Sun. The Faravahar is the most worn pendant amongst Iranians and has become a national symbol, rather than a religious icon because it has been absconded with by non-Zoroastrians, although its Zoroastrian roots should not be ignored. It's the symbol of the state religion of the Persian Empire: Zoroastrianism. Nowadays, it is a common symbol of both the modern and ancient Iranian state (which used to be Persia). Although Zoroastrianism is no longer Iran's state religion, it is an important, customary and traditional symbol. The winged discs has a long history in the art and culture of the ancient Near and Middle East. In Neo-Assyrian times, a human bust is added to the disk, the "feather-robed archer" interpreted as symbolizing Ashur. and the winged disc- Anshar

While the symbol is currently thought to represent a Fravashi (approximately a guardian angel), from which it derives its name (see below), what it represented in the minds of those who adapted it from earlier Mesopotamian and Egyptian reliefs is unclear. Because the symbol first appears on royal inscriptions, it is also thought to represent the 'Divine Royal Glory' (Khvarenah), or the Fravashi of the king, or represented the divine mandate that was the foundation of a king's authority.

This relationship between the name of the symbol and the class of divine entities it represents, reflects the current belief that the symbol represents a Fravashi. However, there is no physical description of the Fravashis in the Avesta, the sacred texts of Zoroastrianism, and in Avestan the entities are grammatically feminine.

Gallery

- Persepolis, Iran.

A Neo-Assyrian "feather robed archer" figure, symbolizing Ashur. The right hand is extended similar to the Faravahar figure, while the left hand holds a bow instead of a ring (9th- or 8th-century BC relief).

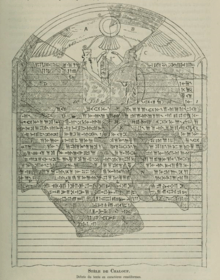

A Neo-Assyrian "feather robed archer" figure, symbolizing Ashur. The right hand is extended similar to the Faravahar figure, while the left hand holds a bow instead of a ring (9th- or 8th-century BC relief). The Faravahar portrayed in the Behistun Inscription

The Faravahar portrayed in the Behistun Inscription National bank of Iran (1946) containing the Farvahar icon.

National bank of Iran (1946) containing the Farvahar icon.- Stone carved Faravahar in Persepolis.

Imperial coat of arms prior to the Revolution, containing Faravahar icon. It was a symbol of the state religion of the Persian Empire: Zoroastrianism. Nowadays, it is a common symbol of both the modern and ancient Iranian state (whose name used to be Persia). Although Zoroastrianism is no longer Iran's state religion, it is an important, customary and traditional symbol.

Imperial coat of arms prior to the Revolution, containing Faravahar icon. It was a symbol of the state religion of the Persian Empire: Zoroastrianism. Nowadays, it is a common symbol of both the modern and ancient Iranian state (whose name used to be Persia). Although Zoroastrianism is no longer Iran's state religion, it is an important, customary and traditional symbol. Faravahar icon at top of the Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions

Faravahar icon at top of the Darius the Great's Suez Inscriptions

References

- ↑ "What Does the Winged Symbol of Zoroastrianism Mean?". About.com Religion & Spirituality. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ↑ "Sacred Symbols". Zoroastrianism for beginners. Retrieved 2017-01-26.

- ↑ Boyce, Mary (15 December 2000). "FRAVAŠI". Encyclopædia Iranica. Retrieved 12 February 2014.

- ↑ MacKenzie, David Neil (1986). A Concise Pahlavi Dictionary. London: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-713559-5.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Faravahar. |