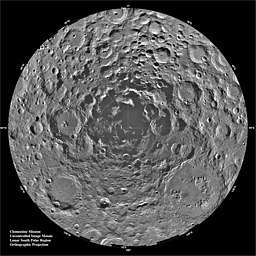

Face on Moon South Pole

The Face on Moon South Pole is a region on the Moon (81.9° south latitude and 39.27° east longitude) that was detected automatically in an image from the Lunar Reconnaissance Orbiter by a computer system using face recognition technologies,[1] as a result of a project that was part of the International Space App Challenge 2013 Tokyo. It is composed of craters and shadows on the moon's surface[2] that, together, form an image resembling a face.

The "Face on Mars" is a better known example.

Face detection and recognition

Human brains have the ability to detect ambiguous images displayed upon the moon due to the brain’s structure.[3] On the left hemisphere of the human brain, the fusiform gyrus (an area linked to recognition), detects the accuracy of how “facelike” an object is. The right fusiform gyrus then uses information from the left fusiform gyrus to conclude whether or not the image is a face.[4] The gyrus's inherent ability to detect faces and patterns in organisms and nature has also led to a phenomenon called Pareidolia, in which the brain detects and recognises faces and patterns in collections of objects where there should be none.

Previous scientific studies have concluded that neurons within the fusiform gyrus react better to faces. An experiment by Massachusetts Institute of Technology brain and cognitive sciences professor Pawan Sinha examined why the right and left fusiform gyrus acknowledges a face, especially when an object greatly resembles a face. In the project Sinha and his students gathered images that resembled human faces and images of genuine faces, which they ran through machine vision systems. This scan resulted in the systems wrongly tagging images as containing faces. Random human participants then ranked how face-like each image was while researchers scanned their brains using functional magnetic resonance imaging.[4]

The researchers found that on the right side of the brain, activity patterns stayed the same for every face except for non-face images, when brain patterns began to change dramatically regardless of whether or not the image resembled a face. On the left side of the brain, activity slowly changed as the images began to resemble a face. This led to the Sinha and the researchers determining that the left side of the brain decides how much an image resembles a face but does not assign them to any classification, while the right side of the brain is the portion that ultimately determines whether or not an image resembles a face.[4]

Craters on the Moon

The craters of the moon that make up the ‘face’ on the south pole have been preserved for billions of years. The moon’s exterior is 16% composed of these craters. These craters have been made by meteors and can be up to 1,600 miles across. Due to the absence of an atmosphere, the moon cannot protect itself from outer threats like these meteors. Craters are often covered with a mixture of fine dust and rocky debris called regolith. Some research conducted through Clementine suggests that there is also water and ice in some craters all over the Moon. The craters themselves show a past of being filled with molten lava.[2]

Face or crater?

Within the Western culture, people have said to have seen “the man in the moon.” Within the East Asian culture, people have seen a rabbit or hands. In addition, various people have seen different imagery such as a tree, a woman, or a toad.[3]

When people describe the images they see on the moon, such as a face, they are not directly seeing that image displayed upon the moon. They are rather looking at an irregular section of the Moon’s surface.[5] The irregular section consists of deep holes, called craters, and hills.

Law of Prägnanz

Humans identify faces where there are none due to a Gestalt Principle called Law of Prägnanz. The Law of Prägnanz states that, “people will perceive and interpret ambiguous or complex images as the simplest form(s) possible.”[6] This means that because the craters and hills of the Moon resemble the shape of eyes and a mouth, the human brain condenses those images into a human face because of familiarity, which is another Gestalt Principle.

Pareidolia

.jpg)

Similar to the Law of Prägnanz, pareidolia is the act of comprehending meaning where it does not exist.[7] Common examples of pareidolia include perceiving the faces of specific religious deities on toast or otherwise seeing faces in things like landscape or wood grain.[8] This human tendency to see faces was something that aided survival during hunter-gatherer times.[9] Reacting to the possible sighting of a predatory animal face, for example, was more likely to result in survival than getting a closer look. Pareidolia partially explains why humans are so inclined to recognize faces on inanimate objects such as the moon.[7]

Other formations in space

The face on the moon is very similar to the face on mars. During the Viking 1 Mission, craters on Mars’ surface caught the public’s eye as it formed an eerily realistic face. While the face on the moon is more inverted, the face on Mars is a three-dimensional mound resembling a human face. The face on Mars was discovered in 1976 but the face on the moon was discovered very recently in 2013. Also, the face on Mars was seen on the middle of the planet while the face on the Moon is on the southern part. The region where the Mars face is called Cydonia. There are also multiple other formations on Mars. There is a specific cluster of mountainous terrain that looks like a smiley face and a skull-like tableland. There is also a volcano that sports a lava flow indentation that strongly resembles Kermit the Frog from the Muppets. There seem to be landscape formations all around the world that remind the human mind of other common images. Some see the Cookie Monster in parts of Mercury and images resembling an eye in the Helix Nebula. On Mercury, you can see a very clear collection of craters that form Mickey Mouse.[10][11]

3D Imagery

Available here.

See also

References

- ↑ "Kurihara, K., Takasu, M., Sasao, K., Seki, H., Narabu, T., Yamamoto, M., Iida, S., Yamamoto, H.: A Face-like Structure Detection on Planet and Satellite Surfaces using Image Processing. ;CoRR(2013)". arXiv:1306.3032. Bibcode:2013arXiv1306.3032K.

- 1 2 "About the Moon". Solar System Exploration. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- 1 2 "Why Do People See Faces in the Moon?". 2017-04-12. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- 1 2 3 "How does our brain know what is a face and what's not?". MIT News. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- ↑ Pitara, Team. "Why do we See a Face on the Moon | Pitara Kids Network". www.pitara.com. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- ↑ "Design Principles: Visual Perception And The Principles Of Gestalt – Smashing Magazine". Smashing Magazine. 2014-03-28. Retrieved 2017-03-18.

- 1 2 "Pareidolia: Why we see faces in hills, the Moon and toasties". BBC News. 2013-05-31. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ "Give Me That Old-Time Pareidolia | Evolution News". Evolution News. 2014-07-10. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ "Woman on Mars? Ghostly Object in NASA Photo Most Likely Dust in the Wind". Newsmax. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ "Faces In Space: Planets, Celestial Formations That Look Like Visages (Photos)". Huffington Post. 2013-01-14. Retrieved 2017-03-20.

- ↑ "The Face on Mars: Fact & Fiction". Space.com. Retrieved 2017-03-20.