Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds

Front page of the original 1841 edition | |

| Author | Charles Mackay |

|---|---|

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | English |

| Subjects | Crowd psychology, economic bubbles, history |

| Publisher | Richard Bentley, London |

Publication date | 1841 |

| Media type | |

Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds is an early study of crowd psychology by Scottish journalist Charles Mackay, first published in 1841.[1] The book was published in three volumes: "National Delusions", "Peculiar Follies", and "Philosophical Delusions".[2] MacKay was an accomplished teller of stories, though he wrote in a journalistic and somewhat sensational style.

The subjects of Mackay's debunking include alchemy, crusades, duels, economic bubbles, fortune-telling, haunted houses, the Drummer of Tedworth, the influence of politics and religion on the shapes of beards and hair, magnetisers (influence of imagination in curing disease), murder through poisoning, prophecies, popular admiration of great thieves, popular follies of great cities, and relics. Present-day writers on economics, such as Michael Lewis and Andrew Tobias, laud the three chapters on economic bubbles.[3]

In later editions, Mackay added a footnote referencing the Railway Mania of the 1840s as another "popular delusion" which was at least as important as the South Sea Bubble. Mathematician Andrew Odlyzko has pointed out, in a published lecture, that Mackay himself played a role in this economic bubble; as leader writer in the Glasgow Argus, Mackay wrote on 2 October 1845: "There is no reason whatever to fear a crash".[4][5]

Volume I: National Delusions

Economic bubbles

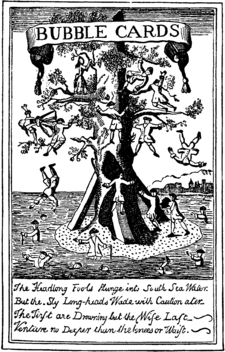

The first volume begins with a discussion of three economic bubbles, or financial manias: the South Sea Company bubble of 1711–1720, the Mississippi Company bubble of 1719–1720, and the Dutch tulip mania of the early seventeenth century. According to Mackay, during this bubble, speculators from all walks of life bought and sold tulip bulbs and even futures contracts on them. Allegedly, some tulip bulb varieties briefly became the most expensive objects in the world during 1637.[6] Mackay's accounts are enlivened by colorful, comedic anecdotes, such as the Parisian hunchback who supposedly profited by renting out his hump as a writing desk during the height of the mania surrounding the Mississippi Company.

Two modern researchers, Peter Garber and Anne Goldgar, independently conclude that Mackay greatly exaggerated the scale and effects of the Tulip bubble,[7] and Mike Dash, in his modern popular history of the alleged bubble, notes that he believes the importance and extent of the tulip mania were overstated.[8]

Chapters in Vol I

- The Mississippi Scheme

- The South Sea Bubble

- The Tulipomania

- Relics

- Modern Prophecies

- Popular Admiration for Great Thieves

- Influence of Politics and Religion on the Hair and Beard

- Duels and Ordeals

- The Love of the Marvellous and the Disbelief of the True

- Popular Follies in Great Cities

- The O.P. Mania

- The Thugs, or Phansigars

Volume II: Peculiar Follies

Crusades

Mackay describes the history of the Crusades as a kind of mania of the Middle Ages, precipitated by the pilgrimages of Europeans to the Holy lands. Mackay is generally unsympathetic to the Crusaders, whom he compares unfavourably to the superior civilisation of Asia: "Europe expended millions of her treasures, and the blood of two millions of her children; and a handful of quarrelsome knights retained possession of Palestine for about one hundred years!"

Witch mania

Witch trials in 16th- and 17th-century Western Europe are the primary focus of the "Witch Mania" section of the book, which asserts that this was a time when ill fortune was likely to be attributed to supernatural causes. Mackay notes that many of these cases were initiated as a way of settling scores among neighbors or associates, and that extremely low standards of evidence were applied to most of these trials. Mackay claims that "thousands upon thousands" of people were executed as witches over two and a half centuries, with the largest numbers killed in Germany and Spain.

Chapters in Vol II

Volume III: Philosophical Delusions

Alchemists

The section on alchemysts focuses primarily on efforts to turn base metals into gold. Mackay notes that many of these practitioners were themselves deluded, convinced that these feats could be performed if they discovered the correct old recipe or stumbled upon the right combination of ingredients. Although alchemists gained money from their sponsors, mainly noblemen, he notes that the belief in alchemy by sponsors could be hazardous to its practitioners, as it wasn't rare for an unscrupulous noble to imprison a supposed alchemist until he could produce gold.

Sections in Vol III

- Book I: The Alchemysts

- Book II: Fortune Telling

- Book III: The Magnetisers

Influence and modern responses

The book remains in print, and writers continue to discuss its influence, particularly the section on financial bubbles. (See Goldsmith and Lewis, below.)

- Financier Bernard Baruch credited the lessons he learned from Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds with his decision to sell all of his stock ahead of the financial crash of 1929.[9]

- The book was the initial inspiration for Richard Condie's National Film Board of Canada animated short John Law and the Mississippi Bubble (1978).[10]

- Forbes magazine compared Mackay's descriptions of financial bubbles to the Chinese stock bubble of 2007, claiming that the "emotional feedback loop" that drove the Chinese market was very similar to what Mackay described.[11]

- Neil Gaiman borrows from the title in an issue of his popular comic series The Sandman, in a story featuring a writer whose novel is titled "...And the Madness of Crowds".[12]

- Author and executive coach Marshall Goldsmith discussed the book in depth in BusinessWeek, drawing extensive parallels between the financial bubbles Mackay wrote about and financial bubbles today.[13] Other writers also frequently point to the book to explain recent financial bubbles.[14][15][16]

- Financial writer Michael Lewis includes the financial mania chapters in his book The Real Price of Everything: Rediscovering the Six Classics of Economics as one of the six great works of economics, along with writings by Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, David Ricardo, Thorstein Veblen, and John Maynard Keynes.[3]

- Author and journalist Will Self writes a column for New Statesman, "Madness of Crowds", which Self says takes its title from Mackay's book.[17]

- James Surowiecki, in The Wisdom of Crowds (2004), takes a different view of crowd behavior, saying that under certain circumstances, crowds or groups may have better information and make better decisions than even the best informed individual.[18]

Quotations

- "Men, it has been well said, think in herds; it will be seen that they go mad in herds, while they only recover their senses slowly, and one by one."

- "Of all the offspring of Time, Error is the most ancient, and is so old and familiar an acquaintance, that Truth, when discovered, comes upon most of us like an intruder, and meets the intruder's welcome."

- "How flattering to the pride of man to think that the stars on their courses watch over him, and typify, by their movements and aspects, the joys or the sorrows that await him! He, in less proportion to the universe than the all-but invisible insects that feed in myriads on a summer's leaf are to this great globe itself, fondly imagines that eternal worlds were chiefly created to prognosticate his fate."

- "We go out of our course to make ourselves uncomfortable; the cup of life is not bitter enough to our palate, and we distill superfluous poison to put into it, or conjure up hideous things to frighten ourselves at, which would never exist if we did not make them."

- "We find that whole communities suddenly fix their minds upon one object, and go mad in its pursuit; that millions of people become simultaneously impressed with one delusion, and run after it, till their attention is caught by some new folly more captivating than the first."

- "The obnoxious hat was often snatched from his head and thrown into the gutter by some practical joker, and then raised, covered with mud, upon the end of a stick, for the admiration of the spectators, who held their sides with laughter, and exclaimed, in the pauses of their mirth, “Oh, what a shocking bad hat!” “What a shocking bad hat!”

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Mackay, Charles (1841). Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. I (1 ed.). London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved 29 April 2015. Mackay, Charles (1841). Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. II (1 ed.). London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved 29 April 2015. Mackay, Charles (1841). Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. III (1 ed.). London: Richard Bentley. Retrieved 29 April 2015.

- ↑ Mackay, Charles (1841). Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. Retrieved 23 March 2018.

- 1 2 Lewis, Michael (2008). The Real Price of Everything.

- ↑ MacKay, Charles (1 December 2008). Extraordinary Popular Delusions, the Money Mania: The Mississippi Scheme, the South-sea Bubble, & the Tulipomania. Cosimo, Inc. p. 88. ISBN 978-1-60520-547-2. Retrieved 8 June 2013.

- ↑ Odyyzko, Andrew (2012). Charles Mackay’s own extraordinary popular delusions and the Railway Mania (PDF). p. 2.

- ↑ "Tulips". library.wur.nl.

- ↑ Garber, Peter M. (2001). Famous First Bubbles.

- ↑ Dash, Mike (2001). Tulipomania: The Story of the World's Most Coveted Flower & the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused.

- ↑ Baruch, Bernard (1957). My Own Story. New York: Henry Holt. pp. 242–245.

- ↑ Ohayon, Albert. "John Law and the Mississippi Bubble: The Madness of Crowds". NFB.ca Blog. National Film Board of Canada. Retrieved 22 June 2011.

- ↑ "China Bubble Mania". Forbes. 2007-05-30. Retrieved 2009-10-30.

- ↑ Gaiman, Neil (1991). The Sandman Vol. 3: Dream Country.

- ↑ "The Madness of Crowds, Past and Present". BusinessWeek. Retrieved 2009-10-01.

- ↑ "The books cashing in on the crash". The Independent. London. 2009-11-20. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ↑ Streitfeld, David; and Healy, Jack (2009-04-29). "Phoenix Leads the Way Down in Home Prices". The New York Times. Retrieved 2009-11-23.

- ↑ Delasantellis, Julian (2007-03-16). "The subprime dominoes in motion". Asia Times. Retrieved 2010-11-15.

- ↑ "To be honest, it's totally random". New Statesman. Retrieved 2009-10-12.

- ↑ Surowiecki, James (2004). The Wisdom of Crowds.

Bibliography

- Dash, Mike (1999). Tulipomania: The Story of the World's Most Coveted Flower and the Extraordinary Passions It Aroused. New York: Crown Publishers. ISBN 978-0-609-60439-7. OCLC 41967050.

- Garber, Peter M. (2000). Famous First Bubbles: The Fundamentals of Early Manias. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-57153-1. OCLC 43552719.

- Goldgar, Anne (2007). Tulipmania: Money, Honor, and Knowledge in the Dutch Golden Age. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-30125-9. OCLC 76897793.

- MacKay, Charles (1980). Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (with a foreword by Andrew Tobias, 1841). New York: Harmony Books. ISBN 978-0-517-54123-4. OCLC 5750576.

- Phillips, Tim (2009). Charles Mackay's Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds: A Modern-day Interpretation of a Finance Classic. Oxford: Infinite Ideas. ISBN 978-1-905-94091-2.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds. |

The book is in the public domain and is available online from a number of sources:

- Mackay, Charles. Memoirs of Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds (Audio Book read by LibriVox volunteers ed.). Librivox.

- Works by Charles Mackay at Project Gutenberg