Ernst Toller

| Ernst Toller | |

|---|---|

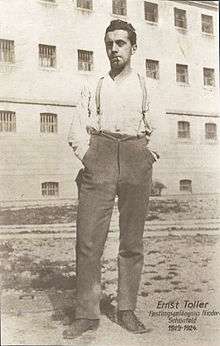

Ernst Toller during his imprisonment in the Niederschönenfeld fortress (early 1920s) | |

| Born |

December 1, 1893 Samotschin, Posen, Germany |

| Died |

May 22, 1939 (aged 45) New York City, United States |

| Nationality | Germany |

Ernst Toller (1 December 1893 – 22 May 1939) was a German left-wing playwright, best known for his Expressionist plays. He served in 1919 for six days as President of the short-lived Bavarian Soviet Republic, and was imprisoned for five years for his actions.[1] He wrote several plays and poetry during that period, which gained him international renown. They were performed in London and New York as well as Berlin. In 2000, several of his plays were published in an English translation.

In 1933 Toller was exiled from Germany after the Nazis came to power. He did a lecture tour in 1936-1937 in the United States and Canada, settling in California for a while before going to New York. He joined other exiles there. Struggling financially and depressed at learning his brother and sister had been sent to a concentration camp in Germany, he committed suicide in May 1939.

Life and career

Toller was born in 1893 into a Jewish family in Samotschin (Szamocin), Province of Posen, Prussia (Posen is now part of Poland). He had a sister and brother. They grew up speaking Yiddish and German, and he later became fluent in English. The most recent biography on Toller is Robert Ellis' Ernst Toller and German Society. Intellectuals as Leaders and Critics published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

At the outbreak of World War I, he volunteered for military duty. After serving for 13 months on the Western Front,[1] he suffered a complete physical and psychological collapse. His first drama, Transformation (Die Wandlung, 1919), was wrought from his wartime experiences.

Together with leading anarchists, such as B. Traven and Gustav Landauer, and communists, Toller was involved in the short-lived 1919 Bavarian Soviet Republic. He served as President from April 6 to April 12. His government did little to restore order in Munich. His government members were not always well-chosen. For instance, the Foreign Affairs Deputy Dr. Franz Lipp (who had been admitted several times to psychiatric hospitals) informed Vladimir Lenin via cable that the ousted former Minister President, Johannes Hoffmann, had fled to Bamberg and taken the key to the ministry toilet with him. On Palm Sunday, April 1919, the Communist Party seized power, with Eugen Leviné as their leader.[2] Shortly after that, the republic was defeated by right-wing forces.

The noted authors Max Weber and Thomas Mann testified on Toller's behalf when he was tried for his part in the revolution. He was sentenced to five years in prison and served his sentence in the prisons of Stadelheim, Neuburg, Eichstätt. From February 1920 until his release, he was in the fortress of Niederschönenfeld, where he spent 149 days in solitary confinement and 24 days on hunger strike.[3]

His time in prison was productive; he completed work on Transformation, which premiered in Berlin under the direction of Karlheinz Martin in September 1919. At the time of this work's 100th performance, the Bavarian government offered Toller a pardon. He refused it out of solidarity with other political prisoners. Toller continued writing in prison, completing some of what would be his most celebrated works, including the dramas Masses Man (Masse Mensch), The Machine Breakers (Die Maschinenstürmer), Hinkemann, the German (Der deutsche Hinkemann), and many poems. These works established him as an important German expressionist playwright, and they used symbols derived from the First World War and its aftermath in his society.

Not until after his release from prison in July 1925 was Toller able to see any of his plays performed. In 1925, the most famous of his later dramas, Hoppla, We're Alive! (Hoppla, wir Leben!), directed by Erwin Piscator, premiered in Berlin. It tells of a revolutionary discharged from a mental hospital after eight years, who discovers that his former comrades have grown complacent and compromised within the system they once opposed. In despair, he kills himself.[4] The most recent study of Toller and his tragic life is Robert Ellis's "Ernst Toller and German Society. Intellectuals as Leaders and Critics" published by Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

Exile

In 1933, after the Nazi rise to power, Toller was exiled from Germany because of his work; the Nazis did not like modernist arts of any form. His citizenship was nullified by the Nazi government later that year. He traveled to London with 16 year old Christiane Grautoff; they married in London in 1935, the same year he participated as co-director in the Manchester production of his play Rake Out the Fires (Feuer aus den Kesseln).

In 1936 and 1937, Toller went on a lecture tour of the United States and Canada, settling in California. Fluent in English, he wrote screenplays but could not get them produced. In 1936 he moved to New York City, where he joined a group of artists and writers in exile, including Klaus Mann, Erika Mann (at one time married to the poet W.H. Auden, who was also in the US), and Therese Giehse. He earned some money from journalism.

Two of his early plays were produced in New York in this period: The Machine Wreckers (1922), whose opening night in 1937 he attended, and No More Peace, produced in 1937 by the Federal Theatre Project and presented in New York City in 1938. Their sense of immediacy was gone: the first play was related to the First World War and its aftermath, and the second an earlier period of the rise of the Nazis. Their style was outmoded for New York, and the poor reception added to Toller's discouragement.[5]

Suffering from deep depression after learning that his sister and brother had been arrested and sent to concentration camps, and struggling with financial woes (he had given all his money to Spanish Civil War refugees), Toller committed suicide on May 22, 1939. He hanged himself in his room[1] at the Mayflower Hotel,[6] after laying out on his hotel desk "photos of Spanish children who had been killed by fascist bombs."[7]

W. H. Auden's poem "In Memory of Ernst Toller" was published in Another Time (1940).

The English author Robert Payne, who knew Toller in Spain and in Paris, later wrote in his diary that Toller had said shortly before his death:

"If ever you read that I committed suicide, I beg you not to believe it." Payne continued: "He hanged himself with the silk cord of his nightgown in a hotel in New York two years ago. This is what the newspapers said at the time, but I continue to believe that he was murdered."[8]

Works

- Transfiguration (Die Wandlung) (1919)

- Masses Man (Masse Mensch) (1921)

- The Machine Wreckers (Die Maschinenstürmer) (1922)

- Hinkemann (org. Der deutsche Hinkemann), Uraufführung (19 September 1923) Produced under titles of The Red Laugh and Bloody Laughter (US)

- Hoppla, We're Alive! (Hoppla, wir leben!) (1927)

- Feuer aus den Kesseln (1930)

- Mary Baker Eddy (1930), play in five acts, with Hermann Kesten

After exile:

- Eine Jugend in Deutschland (A Youth in Germany) (1933), autobiography, Amsterdam

- I Was a German: The Autobiography of a Revolutionary (1934), New York: Paragon

- Nie Wieder Friede! (No More Peace) (1935)[5] First published and produced in English, as he was living in London, but it was written originally in German.

- Briefe aus dem Gefängnis (1935) (Letters from Prison), Amsterdam

- Letters from Prison: Including Poems and a New Version of 'The Swallow Book' (1936), London

In 2000, Alan Pearlman published his translation into English of several of Toller's plays.[9] The literary rights to the works of Ernst Toller were the property of the novelist Katharine Weber until the copyright expired on December 31, 2009. His works have now entered the public domain.

Influence

- The English dramatist Torben Betts has reworked Hinkemann; his play Broken was produced in the UK in 2011.

- Toller was a central character in the Miles Franklin Award-winning novel All That I Am by Anna Funder.

- Paul Schrader's 2017 film First Reformed centers on a troubled, although Protestant, character named for Toller.

References

- 1 2 3 "Ernst Toller". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 Feb 2012.

- ↑ Jeffrey S. Gaab (2006). Munich: Hofbräuhaus & History. Peter Lang. p. 58. ISBN 9780820486062.

- ↑ Dove, Richard (1990). He Was a German: A Biography of Ernst Toller. London: Libris. ISBN 1870352858.

- ↑ Pearlman, Alan Raphael, ed. and trans. 2000. Plays One: Transformation, Masses Man, Hoppla, We're Alive!. By Ernst Toller. Absolute Classics series. London: Oberon. ISBN 1-84002-195-0. pp. 17, 31

- 1 2 Peter Bauland, The Hooded Eagle: Modern German Drama on the New York Stage, Syracuse University Press, 1968, pp. 112-114

- ↑ Fisher, Oscar (August 1939). "The Suicide of Ernst Toller". New International, Vol. 5, No. 8. Retrieved 22 April 2009.

- ↑ Jean-Michel Palmier, Weimar in Exile, pg 360

- ↑ Robert Payne, "Diary entry for May 23, 1942", Forever China (Chungking Diaries), New York: Dodd, Mead, 1945

- ↑ Pearlman, Alan Raphael, ed. and trans. 2000. Plays One: Transformation, Masses Man, Hoppla, We're Alive!. By Ernst Toller. Absolute Classics series. London: Oberon. ISBN 1-84002-195-0

Sources

- Tankred Dorst. Toller (suhrkamp ed.). Suhrkamp Verlag. ISBN 3-518-10294-X.

- Dove, Richard (1990). He was a German: A Biography of Ernst Toller. Libris, London. ISBN 1-870352-85-8.

- Fuld, Werner; Ostermaier(Hrsg.), Albert (1996). Die Göttin und ihr Sozialist: Gristiane Grauthoff - ihr Leben mit Ernst Toller. Weidle Verlag, Bonn. ISBN 3-931135-18-7.

- Ossar, Michael (1980). Anarchism in the Dramas of Ernst Toller: The Realm of Necessity and the Realm of Freedom. State University of New York Press, Albany. ISBN 0873953932.

- Mauthner, Martin (2007). German Writers in French Exile, 1933-1940. London. ISBN 978-0853035411.

- Ellis, Robert; Toller, Ernst; German Society (2013). Intellectuals as Leaders and Critics, 1914-1939. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ernst Toller. |

- Red Yucca - German Poetry in Translation (trans. Eric Plattner)

- There are some Toller-Texts on the Internet. Links of Helmut Schulze.

- http://www.dhm.de/lemo/html/biografien/TollerErnst/index.html

- Links

- Eamonn Fitzgerald's Rainy Day: Prague spring

- Ernst Toller at Find a Grave

- Ernst Toller Page Daily Bleed's Anarchist Encyclopedia

- Ernst-Toller-Gesellschaft e.v. (Ernst Toller Society)

- Newspaper clippings about Ernst Toller in the 20th Century Press Archives of the German National Library of Economics (ZBW)