Erlikosaurus

| Erlikosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

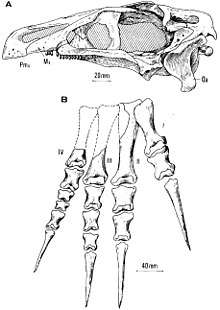

| Skull and foot of the holotype specimen | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Order: | Saurischia |

| Suborder: | Theropoda |

| Family: | †Therizinosauridae |

| Genus: | †Erlikosaurus Perle, 1980 |

| Species: | †E. andrewsi |

| Binomial name | |

| Erlikosaurus andrewsi Perle, 1980 | |

Erlikosaurus is a genus of herbivorous theropod dinosaur from the late Cretaceous Period, belonging to the Therizinosauridae. Its fossils, a skull and some post-cranial fragments, were found in the Bayan Shireh Formation of Mongolia, dating to around 90 million years ago.[1]

Description

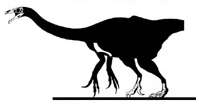

Erlikosaurus were therizinosaurs, a strange group of theropods that ate plants instead of meat, and that had backward-facing pubises like ornithischians. Also like ornithischians, their jaws were tipped by a broad rounded bony beak useful for cropping off plants.[1] Behind the beak, separated by an hiatus, there were per side twenty-three small straight coarsely serrated teeth in the maxilla.[2] The dentary of the lower jaw had more teeth: thirty-one for a total of one hundred eight. The bony nostrils of Erlikosaurus were very large and elongated. The braincase was swollen at the back by pneumatised bone. Scientists now know some therizinosaurs were feathered, so it is likely that Erlikosaurus were as well. Erlikosaurus had exceptionally long slender claws on their feet, with a bone core of up to ten centimetres, the purpose of which is unclear; G.S. Paul surmised they were used for self-defence.[3]

As the genus is only known from very fragmentary material, it has been problematic to determine the size of Erlikosaurus, especially as most of the vertebral column of the holotype is missing. The skull length is twenty-five centimetres; the humerus is thirty centimetres long. It has been estimated to attain an adult body length of six meters (twenty feet). Erlikosaurus may have been more lightly built than close relative Segnosaurus.[1] Other estimates are lower: in 2010 Gregory S. Paul gave a length of 4.5 metres and a weight of half a tonne.[3]

Discovery and naming

The remains of Erlikosaurus were discovered in 1972 at Bayshin Tsav, during a Soviet-Mongolian expedition in Ömnögovi Province. The type species, Erlikosaurus andrewsi, was named and described by Altangerel Perle in 1980, in an article co-authored with Rinchen Barsbold, who however, is not indicated as the name-giver of this particular species. Its generic name was taken from that of the demon king Erlik from Turko-Mongolian mythology and the specific name of the American paleontologist Roy Chapman Andrews.[4] Confusingly, in 1981 Perle again named the species as if it were new, this time spelling the generic name as a Latinised "Erlicosaurus".[5] It is today generally considered that the original name, Erlikosaurus, is valid.

The holotype, IGM 100/111, was found in layers dating from the Cenomanian-Santonian. It consists of a complete skull with lower jaws, some cervical vertebrae fragments, the left humerus and the right foot. At the time it was the only known therizinosaur (then called segnosaurs) for which a skull had been discovered.[1] This helped shed light on a puzzling and poorly known group of dinosaurs. It still represents the most completely known therizinosaurian skull.[2]

Some scientists have speculated that Erlikosaurus may be the same animal as Enigmosaurus mongoliensis named in 1983,[3] since the latter was found in the same geologic formation, and was only known from part of a hip, whereas the pelvis of Erlikosaurus is unknown. This would make Enigmosaurus a junior synonym of Erlikosaurus.[1] However, since the Enigmosaurus hip did not resemble that of Segnosaurus as closely as would be expected for the Segnosaurus-like Erlikosaurus remains and there is a considerable size difference, paleontologist Rinchen Barsbold disputed the alleged synonymy.[1] Consequently, Enigmosaurus and Erlikosaurus are generally still considered separate genera.

Classification

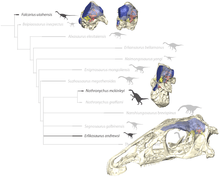

Erlikosaurus was by Perle assigned to the Segnosauridae, a group today known as the Therizinosauridae. This is confirmed by later cladistic analyses.[2]

The following cladogram is based on the phylogenetic analysis by Phil Senter et al., 2012.[6]

| Therizinosauroidea |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Erlikosaurus is poorly known from skeletal material, but it has recently become the focus of study in CT scans that were recently published in December 19, 2012 by Stephen Lautenschlager and Dr Emily Rayfield of Bristol University School of Earth Sciences, Professor Lindsay Zanno of the North Carolina Museum of Natural History and North Carolina State University, and Lawrence Witmer, Chang Professor of Paleontology at the Ohio University Heritage College of Osteopathic Medicine. Analysis of the brain cavity revealed that Erlikosaurus, and quite likely most other therizinosaurids, had well developed senses of smell, hearing, and balance, traits better associated with carnivorous theropods. The enlarged forebrain of Erlikosaurus may also have been useful in complex social behavior and predator evasion.[7][8]

The well preserved jaws of Erlikosaurus also allowed a study by the University of Bristol to determine how its feeding style and dietary preferences were linked to how wide it could open its mouth. In the study, performed by Stephen Lautenshlager et al., It was revealed that Erlikosaurus could open its mouth to a 43 degree angle at maximum. Also included in the study for comparison were the carnivorous theropods Allosaurus and Tyrannosaurus. From the comparisons, it was indicated that carnivorous dinosaurs had wider jaw gapes than herbivores, much as modern carnivorous animals do today.[9][10]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Erlikosaurus." In: Dodson, Peter & Britt, Brooks & Carpenter, Kenneth & Forster, Catherine A. & Gillette, David D. & Norell, Mark A. & Olshevsky, George & Parrish, J. Michael & Weishampel, David B. The Age of Dinosaurs. Publications International, LTD. p. 142. ISBN 0-7853-0443-6.

- 1 2 3 Zanno, Lindsay E. (2010). "A taxonomic and phylogenetic re-evaluation of Therizinosauria (Dinosauria: Maniraptora)". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 8 (4): 503–543. doi:10.1080/14772019.2010.488045.

- 1 2 3 Paul, G.S., 2010, The Princeton Field Guide to Dinosaurs, Princeton University Press p. 159

- ↑ Rinchen Barsbold; Altangerel Perle (1980). "Segnosauria, a new infraorder of carnivorous dinosaurs". Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 25 (2): 187–195.

- ↑ Altangerel Perle (1981). "Noviy segnozavrid iz verchnego mela Mongolii". Trudy - Sovmestnaya Sovetsko-Mongol'skaya Paleontologicheskaya Ekspeditsiya. 15: 50–59.

- ↑ Senter, Paul; Kirkland, James I.; Deblieux, Donald D. (2012). Dodson, Peter, ed. "Martharaptor greenriverensis, a New Theropod Dinosaur from the Lower Cretaceous of Utah". PLoS ONE. 7 (8): e43911. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0043911. PMC 3430620. PMID 22952806.

- ↑ Lautenschlager, Stephan; Rayfield, Emily J.; Altangerel Perle; Zanno, Lindsay E.; Witmer, Lawrence M. (2012). "The Endocranial Anatomy of Therizinosauria and Its Implications for Sensory and Cognitive Function". PLoS ONE. 7 (12): e52289. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0052289.

- ↑ University of Bristol (December 19, 2012). "Inside the head of a dinosaur: Research reveals new information on the evolution of dinosaur senses". Science Daily.

- ↑ University of Bristol (November 3, 2015). "The better to eat you with? How dinosaurs' jaws influenced diet". Science Daily.

- ↑ Lautenschlager, Stephan (November 4, 2015). "Estimating cranial musculoskeletal constraints in theropod dinosaurs". Royal Society Open Science. The Royal Society. doi:10.1098/rsos.150495.