Eric Ravilious

| Eric Ravilious | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

22 June 1903 Acton, London, England |

| Died |

2 September 1942 (aged 39) Kaldadarnes, Iceland |

| Nationality | British |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Watercolour painting, design |

| Spouse(s) | Tirzah Garwood |

Eric William Ravilious (22 July 1903 – 2 September 1942) was an English painter, designer, book illustrator and wood-engraver. He grew up in East Sussex, and is particularly known for his watercolours of the South Downs and other English landscapes, which examine English landscape and vernacular art with an off-kilter, modernist sensibility and clarity. He served as a war artist, and died when the aircraft he was in was lost off Iceland.[1][2]

Life

Ravilious was born on 22 July 1903 in Churchfield Road, Acton, London, the son of Frank Ravilious and his wife Emma (née Ford).[3][4] While he was still a small child the family moved to Eastbourne in Sussex, where his parents ran an antique shop.[5]

He was educated at Eastbourne Grammar School. In 1919 he won a scholarship to Eastbourne School of Art and in 1922 another to study at the Design School at the Royal College of Art. There he became close friends with Edward Bawden[5] (his 1930 painting of Bawden at work is in the collection of the College)[6] and, from 1924, studied under Paul Nash.[7] Nash, an enthusiast for wood engraving, encouraged him in the technique, and was impressed enough by his work to propose him for membership of the Society of Wood Engravers in 1925, and helped him to get commissions.[8]

In 1925 he received a travelling scholarship to Italy and visited Florence, Siena, and the hill towns of Tuscany.[7] Following this he began teaching part-time at the Eastbourne School of Art, and from 1930 taught (also part-time) at the Royal College of Art.[9] In the same year he married Eileen Lucy "Tirzah" Garwood, also an artist and engraver.[10] They would have three children together: John Ravilious; the photographer James Ravilious; and Anne Ullmann, editor of books on her parents and their work.

In 1928 Ravilious, Bawden and Charles Mahoney painted a series of murals at Morley College in South London on which they worked for a whole year.[11] Their work was described by J. M. Richards as "sharp in detail, clean in colour, with an odd humour in their marionette-like figures" and "a striking departure from the conventions of mural painting at that time", but was destroyed by bombing in 1941.[11]

Between 1930 and 1932 Ravilious and Garwood lived in Hammersmith, London, where there is a blue plaque on the wall of their house at the corner of Upper Mall and Weltje Road. When Ravilious and Bawden graduated from the RCA they began exploring the Essex countryside in search of rural subjects to paint. Bawden rented Brick House in Great Bardfield as a base and when he married Charlotte Epton, his father bought it for him as a wedding present. Ravilious and Garwood lodged in Brick House with the Bawdens until 1934 when they purchased Bank House at Castle Hedingham,[12] which is now also marked by a blue plaque. There were eventually several other Great Bardfield Artists. In 1933 Ravilious and his wife painted murals at the Midland Hotel in Morecambe.[13] In November 1933, Ravilious held his first solo exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery in London and 20 of the 37 works displayed were sold.[12]

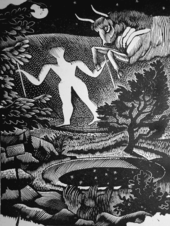

Printmaking and illustration

.jpg)

Ravilious engraved more than 400 illustrations and drew over 40 lithographic designs for books and publications during his lifetime.[14] His first commission, in 1926, was to illustrate a novel for Jonathan Cape. He went on to produce work both for large companies such as the Lanston Corporation and smaller, less commercial publishers, such as the Golden Cockerel Press[8] (for whom he illustrated an edition of Twelfth Night),[15] the Curwen Press and the Cresset Press.[8] His woodcut of two Victorian gentlemen playing cricket has appeared on the front cover of every edition of Wisden Cricketers' Almanack since 1938.[16] His style of wood-engraving was greatly influenced by that of Thomas Bewick.[8] He in turn influenced other wood engravers, such as Gwenda Morgan who also depicted scenes in the South Downs and was commissioned by the Golden Cockerel Press.

In the mid-1930s he took up lithography, making a print of Newhaven Harbour for the "Contemporary Lithographs" scheme, and a set of full-page lithographs, mostly of shop interiors, for a book called High Street, with text by J. M. Richards.[17] Following a trip in a submarine in the war he produced Submarine Dream, a set of 11 lithographs.[18]

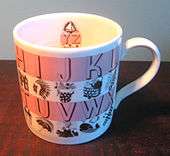

Design

In February 1936, Ravilious held his second exhibition at the Zwemmer Gallery and again it was a success, with 28 out of the 36 paintings shown being sold.[12] This exhibition also led to a commission from Wedgwood for ceramic designs. His work for them included a commemorative mug to mark the abortive coronation of Edward VIII; the design was revised for the coronation of George VI.[12] Other popular Ravilious designs included the Alphabet mug of 1937,[19] and the china sets, Afternoon Tea (1938), Travel (1938), and Garden Implements (1939), plus the Boat Race Day cup in 1938.[20] Production of Ravilious' designs continued into the 1950s, with the coronation mug design being posthumously reworked for the coronation of Elizabeth II in 1953.[21] He also undertook glass designs for Stuart Crystal in 1934, graphic advertisements for London Transport and furniture work for Dunbar Hay in 1936.[20] Ravilious and Bawden were both active in the campaign by the Artists' International Association to support the Republican cause in the Spanish Civil War. Throughout 1938 and 1939, Ravilious spent time working in Wales, the south of France and at Aldeburgh to prepare works for his third one-man show, which was held at the Arthur Tooth & Sons Gallery in 1939.[12]

Watercolour

Apart from a brief experimentation with oils in 1930 – inspired by the works of Johan Zoffany – Ravilious painted almost entirely in watercolour.[15] He was especially inspired by the landscape of the South Downs around Beddingham. He frequently returned to Furlongs, the cottage of Peggy Angus. He said that his time there "altered my whole outlook and way of painting, I think because the colour of the landscape was so lovely and the design so beautifully obvious ... that I simply had to abandon my tinted drawings".[22] Some of his works, such as Tea at Furlongs, were painted there.

Murals

Ravilious was commissioned to paint murals on the walls of the tea room on Victoria Pier at Colwyn Bay in 1934.[23] After the pier's partial collapse, these were thought unrecoverable, but, as of March 2018, one had been recovered in pieces and it was hoped that a second could also be saved, along with parts of another by Mary Adshead, from the pier's auditorium.[23]

Conwy Council's conservation officer, Huw Davies, said:[23]

Only two murals of his survive, and this was the last one in position. It's historically very significant. His work decorated the walls of the tea room and featured an underwater ruin scene with pink and purple seaweed... The murals haven't actually been on show for some time. One wall of the Eric Ravilious work has been lost because of water getting into the building, and the whole thing has been covered over with several coats of paint and plaster. There's a considerable job to do to restore them. For now, they're being stored safely in a dry place... The next stage will be to find a home for them. If the trust succeed in rebuilding the pier, we hope they could return one day.

War artist

.jpg)

.jpg)

Ravilious was accepted as a full-time salaried artist by the War Artists' Advisory Committee in December 1939.[24][lower-alpha 1] He was given the rank of Honorary Captain in the Royal Marines[26] and assigned to the Admiralty. In February 1940, he reported to the Royal Naval barracks at Chatham Dockyard. While based there he painted ships at the dockside, barrage balloons at Sheerness and other coastal defences. Dangerous Work at Low Tide, 1940 depicts bomb disposal experts approaching a German magnetic mine on Whitstable Sands. Two members of the team Ravilious painted were later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[27] On 24 May 1940 Ravilious sailed to Norway aboard HMS Highlander which was escorting HMS Glorious and the force being sent to recapture Narvik. Highlander returned to Scapa Flow before departing for Norway a second time on 31 May 1940. From the deck of Highlander, Ravilious painted scenes of both HMS Ark Royal and HMS Glorious in action. HMS Glorious in the Arctic depicts Hawker Hurricanes and Gloster Gladiators landing on the deck of Glorious as part of the evacuation of forces from Norway on 7/8 June. The following evening Glorious was sunk, with great loss of life.[28]

On returning from Norway, Ravilious was posted to Portsmouth from where he painted submarine interiors at Gosport and coastal defences at Newhaven.[29] After Ravilious's third child was born in April 1941, the family moved out of Bank House to Ironbridge Farm near Shalford, Essex. The rent on this property was paid partly in cash and partly in paintings, which are among the few private works Ravilious completed during the war.[12] In October 1941 Ravilious transferred to Scotland, having spent six months based at Dover. In Scotland, Ravilious first stayed with John Nash and his wife at their cottage on the Firth of Forth and painted convoy subjects from the signal station on the Isle of May. At the Royal Naval Air Station in Dundee, Ravilious drew, and sometimes flew in, the Supermarine Walrus seaplanes based there.[28]

In early 1942, Ravilious was posted to York but shortly afterwards was allowed to return home to Shalford when his wife was taken ill. There he worked on his York paintings and requested a posting to a nearby RAF base while Garwood recovered. He spent a short time at RAF Debden before moving to RAF Sawbridgeworth in Hertfordshire. At Sawbridgeworth he began flying regularly in the de Havilland Tiger Moths based at the flying school there and would sketch other planes in flight from the rear cockpit of the plane.[28]

Death

On 28 August 1942 Ravilious flew to Reykjavík and then travelled on to RAF Kaldadarnes. The day he arrived there, 1 September, a Lockheed Hudson aircraft had failed to return from a patrol. The next morning three planes were despatched at dawn to search for the missing plane and Ravilious opted to join one of the crews. The plane he was on also failed to return and after four days of further searching, the RAF declared Ravilious and the four-man crew lost in action. His body was not recovered and he is commemorated on the Chatham Naval Memorial.[28][30]

In 1946 his widow married Anglo-Irish radio producer Henry Swanzy.

A 1933 painting of Ravilious and Edward Bawden, by Michael Rothenstein, was acquired by the National Portrait Gallery in 2012.[31]

Exhibitions

A touring exhibition organised by the Victor Batte-Lay Trust named "Eric Ravilious 1903 – 1942" was held at The Minories, Colchester in 1972.[32] The Minories held an exhibition on graphic art and book illustration in 2009, named "Graphic art and the art of illustration" which featured Ravilious.[33]

In April to August 2015 the Dulwich Picture Gallery in London held what it called "the first major exhibition to survey" his watercolours, with more than 80 on display.[34][35]

Works by Eric Ravilious are held by the Bristol Museum and Art Gallery, Fry Art Gallery, The Faringdon Collection at Buscot Park, The Ingram Collection of Modern British and Contemporary Art, The Priseman Seabrook Collection and the Victoria and Albert Museum. The largest collection is held at the Towner Art Gallery in Eastbourne.

Towner Art Gallery marked the 75th anniversary of Ravilious' death with Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship[36], a major exhibition created with guest curator Andy Friend that explored the significant relationships and working collaborations between Ravilious and an important group of friends and affiliates, including Paul Nash, John Nash, Enid Marx, Barnett Freedman, Tirzah Garwood, Edward Bawden, Thomas Hennell, Douglas Percy Bliss, Peggy Angus, Helen Binyon, and Diana Low.

References

- ↑ Frances Spalding (1990). 20th Century Painters and Sculptors. Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 1 85149 106 6.

- ↑ Carrington, Noel (1946). "Eric Ravilious". Graphis: 430–9. Retrieved 20 November 2017.

- ↑ Powers, Alan (15 July 2012). Eric Ravilious: Imagined Realities. Philip Wilson Publishers. p. 143. ISBN 978-1-78130-001-5.

- ↑ Russell, James (2015). Ravilious: The Watercolours. Philip Wilson Publishers. p. 1. ISBN 978-1-78130-032-9.

- 1 2 Constable, 1982, p. 14.

- ↑ "Edward Bawden Working in His Studio". Your Paintings. BBC. Retrieved 16 July 2014.

- 1 2 Constable, 1982, p. 16.

- 1 2 3 4 Constable, 1982, p. 17.

- ↑ Constable, 1982, p. 11.

- ↑ Ian Chilvers (Editor) (1988). The Oxford Dictionary of Art. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-860476-9.

- 1 2 Richards, J.M. (1946). Edward Bawden. The Penguin Modern Painters. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. p. 8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 James Russell (2011). Ravilious in Pictures: A Country Life. The Mainstone Press (Norwich). ISBN 0955277760.

- ↑ Constable, 1982, p. 22.

- ↑ Edward Bawden, Design. Antique Collector's Club, Woodbridge, England. ISBN 1-85149-500-2.

- 1 2 Constable, 1982, p. 21.

- ↑ "20 things you never knew about Wisden". Cricinfo. Retrieved 19 August 2009.

- ↑ Constable, 1982, p. 29.

- ↑ Submarine Dream, Goldmark Press

- ↑ Geraldine Bedell (7 December 2003). "Bring me the admiral's bicycle". Observer. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- 1 2 Freda Constable. "Artist biography Eric Ravilious". Tate. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ↑ Jenkins, Stephen (2001). Ceramics of the '50s and '60s. London: Miller's. pp. 8–9.

- ↑ "East Sussex Record Office: Report of the County Archivist, April 2006 to March 2007" (PDF). August 2007. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2011. Retrieved 19 January 2009.

- 1 2 3 Dearden, Chris (12 March 2018). "Bid to save pier murals amid demolition". BBC News. Retrieved 19 March 2018.

- ↑ Imperial War Museum. "War artists archive:Eric Ravilious". Imperial War Museum. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- ↑ "Notes & News". Art And Industry. 1940. Retrieved 14 August 2017.

- ↑ The London Gazette Publication date: 8 March 1940 Issue: 34807 Page: 1394

- ↑ Ministry of Defence. "Ministry of Defence Art Collection". The Ministry of Defence. Retrieved 1 January 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 James Russell (2010). Ravilious In Pictures, The War Paintings. The Mainstone Press. ISBN 978-0955277740.

- ↑ Elizabeth Dooley (30 November 2012). "Submarine". University of Warwick Art Collection. Retrieved 8 October 2016.

- ↑ Casualty Details: Ravilious, Eric William, Commonwealth War Graves Commission.

- ↑ "Portrait – NPG 6938; Eric William Ravilious; Edward Bawden". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 8 September 2014.

- ↑ http://www.abebooks.co.uk/Eric-Ravilious-1903-1942-Minories-Colchester/7960798281/bd

- ↑ Graphic art and the art of illustration: Paul Nash, John Nash, Eric Ravilious, Edward Bawden and their circle. The Minories, Colchester. 2009

- ↑ "Ravilious", Dulwich

- ↑ Richard Dorment (30 March 2015). "Ravilious, Dulwich Picture Gallery, review, A joy from start to finish". The Telegraph. Retrieved 31 August 2015.

- ↑ "Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship | Towner Art Gallery". Towner Art Gallery. Retrieved 2017-09-15.

- ↑ Arts and Industry magazine, whose associate editor was Ravilious' colleague Robert Harling, commented in 1940: "We cannot help thinking that this may seem an odder war to posterity when they see it reproduced in the drawings of Edward Bawden and Eric Ravilious.[25]

Sources

- Constable, Freda (1982). The England of Eric Ravilious. London: Scolar Press.

Further reading

- Andy Friend, Ravilious & Co: The Pattern of Friendship (2017). ISBN 978-0500239551

- Jeremy Greenwood, Ravilious Engravings (2008. Wood Lea Press) [catalogue raisonnee]

- Alan Powers, James Russell, Eric Ravilious: the Story of High Street (2008)

- Alan Powers, Oliver Green. Away We Go! Advertising London's Transport: Eric Ravilious & Edward Bawden (2006)

- Alan Powers, Eric Ravilious: Imagined Realities (2004)

- Richard Morphet. Eric Ravilious in Context (2002)

- Submarine dream: Lithographs and letters (1996)

- Robert Harling. Ravilious and Wedgwood: The Complete Wedgwood Designs of Eric Ravilious (1995), ISBN 978-0903685382

- Helen Binyon. Eric Ravilious. Memoir of an Artist; The Lutterworth Press 2007, Cambridge; ISBN 978-0-7188-2920-9

- R. Dalrymple. Ravilious and Wedgwood (1986. London)

- Eric Ravilious, 1903–42: A Re-assessment of his Life and Work (exh. cat. by P. Andrew, Eastbourne Towner A.G. & Local History Museum) (1986)

- Helen Binyon, Eric Ravilious: Memoir of an Artist (1983) (reprinted 2007)

- Freda Constable and Sue Simon, The England of Eric Ravilious (1982)

- J. M. Richards, The Wood Engravings of Eric Ravilious (1972)

- Anne Ullmann (ed.) Ravilious at War: the complete work of Eric Ravilious, September 1939 – September 1942, contributions from Barry and Saria Viney, Christopher Whittick and Simon Lawrence, foreword by Brian Sewell. Huddersfield, Fleece (2002) ISBN 0-948375-70-1

- James Russell, Ravilious in Pictures: Sussex and the Downs (edited by Tim Mainstone), Mainstone Press, Norwich (2009); ISBN 9780955277733

- James Russell, Ravilious in Pictures: A Travelling Artist (edited by Tim Mainstone), Mainstone Press, Norwich (2012); ISBN 978-0955277788

- James Russell, Ravilious: Submarine (edited by Tim Mainstone), Mainstone Press, Norwich (2013); ISBN 978-0955277795

- Richard Knott, The Sketchbook War. The History Press, 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eric Ravilious. |

- Eric Ravilious, dedicated website

- 5 paintings by or after Eric Ravilious at the Art UK site (excludes watercolours, so only 4 works in tempera)

- Photograph of Ravilious

- Ravilious images at Art Republic