''Ulmus minor'' 'Atinia'

| Ulmus minor 'Atinia' | |

|---|---|

English Elm, Brighton, 1992 | |

| Species | Ulmus minor |

| Cultivar | 'Atinia' |

| Origin | Italy |

The Field Elm cultivar Ulmus minor 'Atinia',[1] commonly known as the English Elm, formerly Common Elm and Horse May,[2] and more lately the Atinian Elm[3] was, before the spread of Dutch elm disease, the most common field elm in central southern England, though not native there, and one of the largest and fastest-growing deciduous trees in Europe. R. H. Richens noted that there are elm-populations in north-west Spain, in northern Portugal and on the Mediterranean coast of France that "closely resemble the English Elm" and appear to be "trees of long standing" in those regions rather than recent introductions.[4][5] Augustine Henry had earlier noted that the supposed English Elms planted extensively in the Royal Park at Aranjuez from the late 16th century onwards, specimens said to have been introduced from England by Philip II[6] and "differing in no respects from the English Elm in England", behaved as native trees in Spain. He suggested that the tree "may be a true native of Spain, indigenous in the alluvial plains of the great rivers, now almost completely deforested".[7]

Richens believed that English Elm was a particular clone of the variable species Ulmus minor, referring to it as Ulmus minor var. vulgaris.[8] A 2004 survey of genetic diversity in Spain, Italy and the UK confirmed that English Elms are indeed genetically identical, clones of a single tree, said to be Columella's 'Atinian Elm',[9] once widely used for training vines, and assumed to have been brought to the British Isles by Romans for that purpose.[10] Thus, despite its name, the origin of the tree is widely believed to be Atina in Italy,[9][11] the home town of Columella, whence he imported it to his vineyards in Cadiz,[12] although the clone is no longer found in Atina and has not yet been identified further east.[13]

Dr Max Coleman of the Royal Botanic Garden, Edinburgh writes (2009): "The advent of DNA fingerprinting has shed considerable light on the question. A number of studies have now shown that the distinctive forms that Melville elevated to species and Richens lumped together as field elm are single clones, all genetically identical, that have been propagated by vegetative means such as cuttings or root suckers. This means that enigmatic British elms such as ... English Elm have turned out to be single clones of field elm."[14] Most floras and field guides, however, do not list English Elm as a form of Ulmus minor, but rather as Ulmus procera.

Synonyms (chronological)

- Ulmus sativa Mill.[15]

- Ulmus campestris L. var. vulgaris Aiton [16]

- Ulmus procera Salisb.[17]

- Ulmus atinia J. Walker [18]

- Ulmus surculosa Stokes[19]

- [Ulmus suberosa Smith, Loudon, Lindley - disputed]

- Ulmus minor Mill. var. vulgaris (Aiton) Richens [20]

- Ulmus minor Mill. subsp. procera (Salisb.) Franco.[21]

- Ulmus procera 'Atinia' [22]

Description

The tree often exceeded 40 m (about 130 feet) in height with a trunk < 2 m (6.5 feet) d.b.h.[23] The largest specimen ever recorded in England, at Forthampton Court, near Tewkesbury, was 46 m (151 feet) tall.[7] While the upper branches form a fan-shaped crown, heavy more horizontal boughs low on the bole often give the tree a distinctive 'figure-of-eight' silhouette. The small, reddish-purple hermaphrodite apetalous flowers appear in early spring before the leaves. The samara is nearly orbicular.[24] The leaves are dark green, almost orbicular, < 10 cm long, without the pronounced acuminate tip at the apex typical of the genus. They flush a lighter green in April, about a month earlier than most Field Elm. Since the tree does not produce long shoots in the canopy, it does not develop the markedly pendulous habit of some Field Elm. The bark of old trees is scaly, unlike the vertically-furrowed bark of ancient Field Elm. The bark of English Elm suckers, like that of Dutch Elm suckers and of some Field Elm, can be corky, but Dutch Elm suckers may be distinguished from English by their straighter, stouter twigs, bolder 'herringbone' pattern, and later flushing.

The tree does not produce fertile seed as it is female-sterile, and natural regeneration is entirely by root suckers.[8][25] Seed production in England was often unknown in any case.[26] By the late 19th century, urban specimens in Britain were often grafted on to wych elm root-stock to eliminate suckering; Henry noted that this method of propagation seldom produced good specimens.[7]

English Elm at Powderham, before 1913

English Elm at Powderham, before 1913 English Elm, 1904

English Elm, 1904 Bark of English Elm

Bark of English Elm Leaves from a specimen tree in Sussex, England (2009)

Leaves from a specimen tree in Sussex, England (2009) Dried short-shoot leaves of mature trees in Edinburgh (August)

Dried short-shoot leaves of mature trees in Edinburgh (August) Juvenile leaves in hedgerow

Juvenile leaves in hedgerow

Pests and diseases

Owing to its homogeneity, the tree has proven particularly susceptible to Dutch elm disease, but immature trees remain a common feature in the English countryside courtesy of the ability to sucker from roots. After about 20 years, these suckers too become infected by the fungus and killed back to ground level. English Elm was the first elm to be genetically engineered to resist disease, at the University of Abertay Dundee.[27] It was an ideal subject for such an experiment, as its sterility meant there was no danger of its introgression into the countryside.

In the United States, English Elm was found to be one of the most preferred elms for feeding by the Japanese Beetle Popillia japonica.[28]

The leaves of the English Elm in the UK are mined by Stigmella ulmivora.

Uses

|

... He liked to be alone, feeling his soul heavy with its own fate. He would sit for hours watching the elm trees standing in rows like giants, like warriors across the country. The Earl had told him that the Romans had brought these elms to Britain. And he seemed to see the spirit of the Romans in them still. Sitting there alone in the spring sunshine, in the solitude of the roof, he saw the glamour of this England of hedgerows and elm trees, and the labourers with slow horses slowly drilling the sod, crossing the brown furrow, and the chequer of fields away to the distance. |

| – From D. H. Lawrence, The Ladybird (1923).[29] |

The English Elm was once valued for many purposes, notably as water pipes from hollowed trunks, owing to its resistance to rot in saturated conditions. It is also very resilient to crushing damage and these two properties led to its widespread use in the construction of jetties, timber piers and lock gates, etc. It was used to a degree in furniture manufacture but not to the same extent as oak, because of its greater tendency to shrink, swell and split, which also rendered it unsuitable as the major timber component in shipbuilding and building construction. The wood has a density of around 560 kg per cubic metre.[30]

However, English Elm is chiefly remembered today for its aesthetic contribution to the English countryside. In 1913 Henry Elwes wrote that "Its true value as a landscape tree may be best estimated by looking down from an eminence in almost any part of the valley of the Thames, or of the Severn below Worcester, during the latter half of November, when the bright golden colour of the lines of elms in the hedgerows is one of the most striking scenes that England can produce".[7]

Cultivation

The introduction of the Atinian elm to Spain from Italy is recorded by the Roman agronomist Columella.[31] It has also been identified by Heybroek as the elm grown in the vineyards of the Valais, or Wallis, canton of Switzerland.[32][33][34] Although there is no record of its introduction to Britain from Spain, it has long been believed[35] that the tree arrived with the Romans, a hypothesis supported by the discovery of pollen in an excavated Roman vineyard. It is likely the tree was used also as a source of leaf hay.[13] Elms said to be English Elm, and reputedly brought to Spain from England by Philip II, were planted extensively in the Royal Park at Aranjuez and the Retiro Park, Madrid from the late 16th century onwards (see Hybrids below).[8][36]

More than a thousand years after the departure of the Romans from Britain, English Elm found far greater popularity, as the preferred tree for planting in the new hawthorn hedgerows appearing as a consequence of the Enclosure movement, which lasted from 1550 to 1850. In parts of the Severn Valley, the tree occurred at densities of over 1000 per square kilometre, so prolific as to have been known as the 'Worcester Weed'.[37] In the eastern counties of England, however, hedgerows were usually planted with local Field Elm, or with suckering hybrids.[38] When elm became the tree of fashion in the 18th and 19th centuries, avenues and groves of English Elm were often planted, among them the elm-groves in The Backs, Cambridge.[39]

English Elm was introduced into Ireland,[40] and as a consequence of Empire has been cultivated in eastern North America and widely in south-eastern Australia and New Zealand. It is still commonly found in Australia and New Zealand, where it is regarded at its best as a street or avenue tree.[41][42][43] It was also planted as a street tree on the American West Coast, notably in St Helena, California,[44] and it has been planted in South Africa.[45]

St Peter's Church, Preston Village, Brighton, with English Elms regrowing after lopping (1951) (Photo: Les Whitcomb)

St Peter's Church, Preston Village, Brighton, with English Elms regrowing after lopping (1951) (Photo: Les Whitcomb) English Elms in hedgerow, Alfriston, East Sussex (1996)

English Elms in hedgerow, Alfriston, East Sussex (1996) Hourglass-shaped English Elm, Preston Park, Brighton (1992)

Hourglass-shaped English Elm, Preston Park, Brighton (1992)- English Elm, Preston Park, Brighton (2004)

Winter silhouette of English Elm, Brighton (2009)

Winter silhouette of English Elm, Brighton (2009) English Elms on Royal Parade, Parkville, Melbourne (2012)

English Elms on Royal Parade, Parkville, Melbourne (2012)- English Elms in Cootamundra, New South Wales, one trimmed for power line (2015)

Notable trees

Mature English Elms are now only very rarely found in the UK beyond Brighton (see below) and Edinburgh. One large tree survives in Leicester in Cossington Street Recreation Ground. Several survive in Edinburgh (2015): one in Rosebank Cemetery (girth 3 metres), one in Founders Avenue, Fettes College, and one in Inverleith Park (east avenue), while a majestic open-grown specimen (3 metres) in Claremont Park, Leith Links, retains the dense fan-vaulted crown iconic in this cultivar. There is an isolated mature English Elm in the cemetery at Dervaig, Isle of Mull, Scotland.

Some of the most significant remaining stands are to be found overseas, notably in Australia where they line the streets of Melbourne, protected by geography and quarantine from disease.[46][47] An avenue of 87 English Elms, planted c.1880, lines the entrance to the winery of All Saints Estate, Rutherglen, Victoria;[48] a double avenue of 400 English Elms, planted in 1897 and 1910–15, lines Royal Parade, Parkville, Melbourne.[49][50][51] Large free-standing English Elms in Tumut, New South Wales,[52] and Traralgon, Victoria,[53] show the 'un-English' growth-form of the tree in tropical latitudes.[54] However, many of the Australian trees, now over 100 years old, are succumbing to old age, and are being replaced with new trees raised by material from the older trees budded onto Wych Elm Ulmus glabra rootstock.[55] In New Zealand a "massive individual" stands at 36 Mt Albert Road, Auckland.[41] In the United States, several fine trees survive at Boston Common, Boston, and in New York City,[56] notably the Hangman's Elm in Washington Square Park,[57] while in Canada four 130-year English Elms, inoculated against disease, survive on the Back Campus field of the University of Toronto.[58] An English Elm planted c.1872 (girth 5.1 m) stands in Kungsparken, Malmö, Sweden.[59]

One of three English Elms (lower branches removed) around which the Crystal Palace was built for the Great Exhibition, 1851[60]

One of three English Elms (lower branches removed) around which the Crystal Palace was built for the Great Exhibition, 1851[60] A coloured lithograph of the same tree (1851)

A coloured lithograph of the same tree (1851) English Elm avenue in Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne (2006)

English Elm avenue in Fitzroy Gardens, Melbourne (2006) Hangman's Elm, Washington Square Park, New York (2007)

Hangman's Elm, Washington Square Park, New York (2007) One of two large English Elms near Trophy Point at West Point, NY (2009)

One of two large English Elms near Trophy Point at West Point, NY (2009)

One of the last old English Elms in Edinburgh (2016)

One of the last old English Elms in Edinburgh (2016)

Brighton and the 'cordon sanitaire'

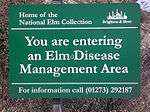

Although the English Elm population in Britain was almost entirely destroyed by Dutch elm disease, mature trees can still be found along the south coast Dutch Elm Disease Management Area in East Sussex. This 'cordon sanitaire', aided by the prevailing south westerly onshore winds and the topographical niche formed by the South Downs, has saved many mature elms. Amongst these are possibly the world's oldest surviving English Elms, known as the 'Preston Twins' in Preston Park, both with trunks exceeding 600 cm in circumference (2.0 m d.b.h.) though the larger tree lost two limbs in August 2017 following high winds.[62][63]

Sign on A27 road, Brighton, England

Sign on A27 road, Brighton, England- The oldest known English Elms in the UK, the 'Preston Twins', Brighton, 2008

The larger of the twins, 2006

The larger of the twins, 2006

Cultivars

A small number of putative cultivars have been raised since the 18th and early 19th centuries,[64] three of which are now almost certainly lost to cultivation: 'Acutifolia', 'Atinia Variegata', 'Folia Aurea', 'Atinia Pyramidalis'. Though usually listed as an English Elm cultivar, Ulmus 'Louis van Houtte' "cannot with any certainty be referred to as Ulmus procera [ = 'Atinia'] " (W. J. Bean).[23] In Sweden, U. × hollandica 'Purpurascens', though not a form of English Elm, is known as Ulmus procera 'Purpurea'.[65]

Hybrids, hybrid cultivars, and mutations

Crossability experiments conducted at the Arnold Arboretum in the 1970s apparently succeeded in hybridizing English Elm with U. glabra and U. rubra, both also protogynous species. However, the same experiments also shewed English Elm to be self-compatible which, in the light of its proven female-sterility, must cast doubt on the identity of the specimens used.[66] A similar doubt must hang over Henry's observation that the 'English Elms' at Aranjuez (see Cultivation above) "produced every year fertile seed in great abundance",[67] seed said to have been taken "all over Europe", presumably in the hope that it would grow into trees like the royal elms of Spain.[68] Given that English Elm is female-sterile, the Aranjuez elms either were not after all English Elm, or, by the time Henry collected seed from them, English Elms there had been replaced by intermediates or by other kinds. At higher altitudes in Spain, Henry noted, such as in Madrid and Toledo, the 'English Elm' did not set fertile seed.[69]

The 2004 study, which examined "eight individuals classified as English Elm" collected in Lazio, Spain and Britain, noted "slight differences among the AFLP fingerprinting profiles of these eight samples, attributable to somatic mutations".[9] Since 'Atinia', though female infertile, is an efficient producer of pollen and should be capable of acting as a pollen parent, it is compatible with the 2004 findings that, in addition to a core population of genetically virtually identical trees deriving from a single clone, there exist intermediate forms of U. minor of which that clone was the pollen parent. These might be popularly or even botanically regarded as 'English Elm', though they would be genetically distinct from it; and in these, the female infertility could have gone. The "smooth-leaved form" of English Elm mentioned by Richens (1983),[8] and the "northern form" mentioned by Oliver Rackham (1986) as having been introduced to Massachusetts,[70] are possible examples of 'Atinia' mutations or intermediates.

In art and photography

The elms in the Suffolk landscape-paintings and drawings of John Constable were not English Elm but "most probably East Anglian hybrid elms ... such as still grow in the same hedges" in Dedham Vale and East Bergholt,[71] while his Flatford Mill elms were U. minor.[72] Constable'sStudy of an elm tree (c.1821) is, however, thought to depict the bole of an English Elm with its bark "cracked into parched-earth patterns".[73] Among artists who depicted English Elms were Edward Seago[74] and James Duffield Harding. English Elm features in oil paintings by the contemporary artist David Shepherd, either as the main subject (Majestic elms ) or more often as the background to nostalgic evocations of farming scenes.[75]

Among classic photographs of English Elm are those by Edward Step and Henry Irving in Wayside and Woodland Trees, A pocket guide to the British sylva (1904).[76]

Constable, Study of an elm tree (c.1821)

Constable, Study of an elm tree (c.1821) 'Figure-of-eight' shaped English Elms, Hyde Park: James Duffield Harding's The Great Exhibition of 1851

'Figure-of-eight' shaped English Elms, Hyde Park: James Duffield Harding's The Great Exhibition of 1851

Accessions

North America

- Longwood Gardens. Acc. no. L-2507.

- Morton Arboretum. Acc. nos. 211-40, 756-60, 351-70.

Europe

- Brighton & Hove City Council, NCCPG Elm Collection.[78] UK champion: Preston Park, 15 m high (storm damaged), 201 cm d.b.h. in 2001.[79] Brighton & Hove has some 700 trees; the most notable examples are at Preston Park, South Victoria Gardens, Royal Pavilion Gardens, The Level, Holmes Avenue, University of Sussex Campus; Preston Road (A23) and Hanover Crescent.

- Grange Farm Arboretum, Sutton St James, Spalding, Lincolnshire, England. Acc. no. 518.

- Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh, as Ulmus procera. Acc. no. 20081448.[80]

- Strona Arboretum, University of Life Sciences, Warsaw, Poland. No details available.

- University of Copenhagen, Botanic Garden. One specimen, no details available.

- Westonbirt Arboretum,[81] Tetbury, Glos., England. Four trees, listed as U. minor var. vulgaris; no acc. details available.

Australasia

- Avenue of Honour, Ballarat, Australia. Details not known.

- Eastwoodhill Arboretum,[82] Gisborne, New Zealand. 12 trees, details not known.

- Waite Arboretum,[83] University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia. No details available.

See also

References

- ↑ Coleman, M.; A’Hara, S.W.; Tomlinson, P.R.; Davey, P.J. (2016). "Elm clone identification and the conundrum of the slow spread of Dutch Elm Disease on the Isle of Man". New Journal of Botany. 6 (2–3): 79–89.

- ↑ Davey, Frederick Hamilton (1909). Flora of Cornwall. p. 401. Republished 1978 by EP Publishing, Wakefield. ISBN 0-7158-1334 X

- ↑ Adams, Ken (2006). "A Reappraisal of British Elms based on DNA Evidence". Essex botany and mycology groups. Archived from the original on 2016-03-04. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ Richens, R. H., Elm (Cambridge, 1983), p.18, p.90

- ↑ Specimen of tree labelled U. procera in Portugal, icnf.pt

- ↑ Richens, R. H., Elm (Cambridge, 1983), p.276

- 1 2 3 4 Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland. Vol. VII. 1848–1929. Republished 2004 Cambridge University Press, ISBN 9781108069380

- 1 2 3 4 Richens, R. H., Elm, Cambridge University Press, 1983

- 1 2 3 Gil, L.; et al. (2004). "English Elm is a 2,000-year-old Roman Clone" (PDF). Nature. London: Nature Publishing Group. 431: 1053. .

- ↑ Tree News, Spring/Summer 2005, Publisher Felix Press

- ↑ "English elm 'brought by Romans'". BBC. 2004-10-28. Retrieved 2008-12-21.

- ↑ Tovar, A. (1975). Columella y el vino de Jerez. in: Homenaje nacional a Lucio Junio Moderato Columela Asociación de Publicistas y Escritores Agrarios Españoles, Cadiz. 93-99.

- 1 2 Heybroek, Hans M, 'The elm, tree of milk and wine' (2013), sisef.it/iforest/contents/?id=ifor1244-007

- ↑ Max Coleman, ed.: Wych Elm (Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh publication, 2009; ISBN 978-1-906129-21-7); p. 22

- ↑ Miller, Philip (1768). The gardeners dictionary. 3 (8 ed.). p. 674.

- ↑ Aiton, William (1789). Hortus Kewensis. 1. p. 319.

- ↑ Salisbury, Richard Anthony (1796). Prodromus stirpium in horto ad Chapel Allerton vigentium. p. 391.

- ↑ Walker, John (1808). Essays on natural history and rural economy. pp. 70–72.

- ↑ Stokes, Jonathan (1812). A botanical materia medica. 2. p. 35.

- ↑ Richens, Richard Hook (1977). "New Designations in Ulmus minor Mill". Taxon. 26: 583–584.

- ↑ do Amaral Franco, João Manuel Antonio (1992). "Notas Breves" (PDF). Anales del Jardín Botánico de Madrid. 50 (2): 259.

- ↑ Heybroek, Hans (2003). "Die vierte deutsche Ulme? Ein Baum mit Geschichte". Mitteilungen der Deutschen Dendrologischen Gesellschaft. 88: 117–119.

- 1 2 Bean, W. J. (1981). Trees and shrubs hardy in Great Britain. Murray, London.

- ↑ Ley, Augustin (1910). "Notes on British elms". Journal of botany, British and foreign. 48: 65–72. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ White, J. & More, D. (2002). Trees of Britain & Northern Europe. Cassell, London

- ↑ Hanson, M. W. (1990). Essex elm. London: Essex Field Club. ISBN 978-0-905637-15-0. Retrieved 2017-10-24.

- ↑ Meek, James (2001-08-28). "Scientists modify elm to resist disease that killed millions of trees in Britain". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ↑ Miller, F., Ware, G. and Jackson, J. (2001). Preference of Temperate Chinese Elms (Ulmuss spp.) for the Feeding of the Japanese Beetle (Coleoptera: Scarabaeidae). Journal of Economic Entomology 94 (2). pp 445-448. 2001. Entom. Soc.of America.

- ↑ D. H. Lawrence, The Ladybird (Penguin edition, 1960, p.69)

- ↑ Elm. Niche Timbers. Accessed 19-08-2009.

- ↑ Columella, Lucius Junius Moderadus (c.A D 50) De re rustica, v.6

- ↑ "bioportal.naturalis.nl L.4214289 Ulmus procera 'Atinia'". Archived from the original on 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ "bioportal.naturalis.nl L.4214286 Ulmus procera 'Atinia'". Archived from the original on 2017-10-26. Retrieved 2017-10-26.

- ↑ "bioportal.naturalis.nl L.4214283 Ulmus procera 'Atinia'". Archived from the original on 2017-10-28. Retrieved 2017-10-28.

- ↑ Loudon, John Claudius, Arboretum et fruticetum Britannicum; or, The trees and shrubs of Britain, Vol. 3 (1838)

- ↑ Elwes, H. J., & Henry, A., The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland (Private publication, Edinburgh, 1913), Vol. VII, p.1908

- ↑ Wilkinson, G. (1984). Trees in the Wild and Other Trees and Shrubs. Stephen Hope Books. ISBN 0-903792-05-2.

- ↑ Richens, R. H., Elm (Cambridge, 1983), Ch.14

- ↑ Photographs of English Elm in The Backs in 101 Views of Cambridge, Rock Bros. Ltd., c.1900

- ↑ Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol.7, p.1920

- 1 2 Wilcox, Mike; Inglis, Chris (2003). "Auckland's elms" (PDF). Auckland Botanical Society Journal. Auckland Botanical Society. 58 (1): 38–45.

- ↑ Lefoe, Gregory K., 'Elm Trees', emelbourne.net.au

- ↑ Victorian Heritage Database

- ↑ Dreistadt, S, Dahlsten, D. L., and Frankie, G. W. (1990). Urban Forests and Insect Ecology. BioScience. Vol. 40, No. 3 (March 1990). pp. 192 - 198. University of California Press.

- ↑ Troup, R. S. (1932). Exotic forest trees in the British Empire. Oxford Clarendon Press. ASIN: B0018EQG9G

- ↑ Spencer, R., Hawker, J. and Lumley, P. (1991). Elms in Australia. Australia: Royal Botanic Gardens, Melbourne. ISBN 0-7241-9962-4

- ↑ Photograph of English Elm in Melbourne, 2.bp.blogspot.com

- ↑ English Elm avenue, All Saints Estate, Rutherglen, allsaintswine.com.au , rutherglenvic.com , 2bustickets.blogspot.co.uk l

- ↑ English Elm in Melbourne, emelbourne.net.au , gardendrum.com

- ↑ English Elm in Victoria, Victorian Heritage Database, procera:1 procera:2

- ↑ English Elms on Royal Parade, Melbourne, flickr.com

- ↑ Ernest H. Wilson, 'Northern Trees in Southern Lands', Journal of the Arnold Arboretum, Vol.IV, No.2, April 1923, p.83

- ↑ English Elm in Traralgon, Victoria, vhd.heritage.vic.gov.au

- ↑ 'The growth and ultimate form of English Elm', resistantelms.co.uk

- ↑ Fitzgibbon, J. (2006) Royal Parade Elm Replacement. Elmwatch, Vol. 16 No. 1, March 2006

- ↑ English Elm in Central Park, New York, centralpark-ny.com

- ↑ Barnard, E. S. (2002). New York City Trees. Columbia University Press

- ↑ Photograph of English Elms in University of Toronto: Janet Harrison, nativeplantwildlifegarden.com

- ↑ Lagerstedt, Lars (2014). "Märkesträd i Sverige - 10 Almar" [Notable trees in Sweden - 10 Elms] (PDF). Lustgården. 94: 59. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ↑ Clouston, B., Stansfield, K., eds., After the Elm (London, 1979), p.55

- ↑ The Conservation Foundation's Great British Elm Experiment map of parent trees: Archived 2015-01-09 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Europe's biggest elm tree splits in two and crashes to the ground". Mail Online. 21 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- ↑ "Scramble to save the oldest elm in world". The Argus. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 2017-08-22.

- ↑ Green, Peter Shaw (1964). "Registration of cultivar names in Ulmus". Arnoldia. Arnold Arboretum, Harvard University. 24 (6–8): 41–80. Retrieved 16 February 2017.

- ↑ Lars Lagerstedt, 'Almar i Sverige', Lustgarden, 2014, p.60, p.76, p.71

- ↑ Hans, A. S. (1981). Compatibility and Crossability Studies in Ulmus. Silvae Genetica 30, 4 - 5 (1981).

- ↑ Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol.7, p.1908

- ↑ Wilkinson, Gerald, Epitaph for the Elm (London, 1978), p.115

- ↑ Elwes, H. J. & Henry, A. (1913). The Trees of Great Britain & Ireland, Vol.7, p.1908

- ↑ Rackham, Oliver, The History of the Countryside (London, 1986)

- ↑ R. H. Richens, Elm, p.166, 179

- ↑ Richens, R. H., Elm (Cambridge 1983), p.173; p.293, note 26

- ↑ 'Elm' by Robert Macfarlane, vam.ac.uk/content/articles/m/memory-maps-elm-by-robert-macfarlane/

- ↑ Edward Seago, Elm Trees near Cookham, telegraph.co.uk/comment/letters/8571179/Last-chance-to-save-the-surviving-English-elms.html

- ↑ English Elm in David Shepherd landscapes, davidshepherd.com/davidshepherd-farm.html

- ↑ Step, Edward, Wayside and Woodland Trees, Plate 36, gutenberg.org/files/34740/34740-h/34740-h.htm

- ↑ Photographs of English Elms on the Backs in 101 Views of Cambridge, Rock Bros Ltd, c.1900

- ↑ "List of plants in the {elm} collection". Brighton & Hove City Council. Retrieved 23 September 2016.

- ↑ Johnson, Owen (ed.) (2003). Champion Trees of Britain & Ireland. Whittet Press, ISBN 978-1-873580-61-5.

- ↑ Royal Botanic Garden Edinburgh. (2017). List of Living Accessions: Ulmus

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-10-12. Retrieved 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Archived October 14, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Waite Arboretum | Waite Arboretum". Waite.adelaide.edu.au. 2003-01-21. Retrieved 2012-11-02.

External links

- Jobling & Mitchell, 'Field Recognition of British Elms', Forestry Commission Booklet

- https://web.archive.org/web/20070222232826/http://redwood.mortonarb.org/PageBuilder?cid=2&qid= Morton Arboretum Catalogue 2006

- Adams, K., 'A Reappraisal of British Elms based on DNA Evidence' (2006)

- Heybroek, Hans M, 'The elm, tree of milk and wine' (2013)

- "Herbarium specimen - L.4214471". Botany catalogues. Naturalis Biodiversity Center. Samara of U. procera, Hunsdon (Kew Herbarium specimen)