English-language spelling reform

For centuries, there has been a movement to reform the spelling of English. It seeks to change English spelling so that it is more consistent, matches pronunciation better, and follows the alphabetic principle.[1]

Common motives for spelling reform include quicker, cheaper learning, thus making English more useful for international communication.

Reform proposals vary in terms of the depth of the linguistic changes and by the ways they are implemented. In terms of writing systems, most spelling reform proposals are moderate; they use the traditional English alphabet, try to maintain the familiar shapes of words, and try to maintain common conventions (such as silent e). More radical proposals involve adding or removing letters or symbols, or even creating new alphabets. Some reformers prefer a gradual change implemented in stages, while others favor an immediate and total reform for all.

Some spelling reform proposals have been adopted partially or temporarily. Many of the spellings preferred by Noah Webster have become standard in the United States, but have not been adopted elsewhere (see American and British English spelling differences). Harry Lindgren's proposal, SR1, was popular in Australia at one time.

Spelling reform has rarely attracted widespread public support, and has sometimes met organized resistance from the educated majority who do not need a reform.

There are linguistic arguments against and for reform, for example that the origins of words may be obscured, or on the contrary that current orthography obscures much. Another argument is that the cost of wholesale change would be large. However, many texts are in computers, and can easily be transcoded to serve new and old readers.

History

Modern English spelling developed from about AD 1350 onwards, when—after three centuries of Norman French rule—English gradually became the official language of England again, although very different from before 1066, having incorporated many words of French origin (battle, beef, button, etc.). Early writers of this new English, such as Geoffrey Chaucer, gave it a fairly consistent spelling system, but this was soon diluted by Chancery clerks who re-spelled words based on French orthography. English spelling consistency was dealt a further blow when William Caxton brought the printing press to London in 1476. Having lived in mainland Europe for the preceding 30 years, his grasp of the English spelling system had become uncertain. The Belgian assistants he brought to help him set up his business had an even poorer command of it.

As printing developed, printers began to develop individual preferences or "house styles".[2] Furthermore, typesetters were paid by the line and were fond of making words longer. However, the biggest change in English spelling consistency occurred between 1525, when William Tyndale first translated the New Testament, and 1539, when King Henry VIII legalized the printing of English Bibles in England. The many editions of these Bibles were all printed outside England by people who spoke little or no English. They often changed spellings to match their Dutch orthography. Examples include the silent h in ghost (to match Dutch gheest, which later became geest), aghast, ghastly and gherkin. The silent h in other words—such as ghospel, ghossip and ghizzard—was later removed.[3]

There have been two periods when spelling reform of the English language has attracted particular interest.

16th and 17th centuries

The first of these periods was from the middle of the 16th to the middle of the 17th centuries AD, when a number of publications outlining proposals for reform were published. Some of these proposals were:

- De recta et emendata linguæ angliæ scriptione (On the Rectified and Amended Written English Language)[4] in 1568 by Sir Thomas Smith, Secretary of State to Edward VI and Elizabeth I.

- An Orthographie in 1569 by John Hart, Chester Herald.

- Booke at Large for the Amendment of English Orthographie in 1580 by William Bullokar.

- Logonomia Anglica in 1621 by Dr. Alexander Gill, headmaster of St Paul's School in London.

- English Grammar in 1634 by Charles Butler, vicar of Wootton St Lawrence.[5]

These proposals generally did not attract serious consideration because they were too radical or were based on an insufficient understanding of the phonology of English.[6] However, more conservative proposals were more successful. James Howell in his Grammar of 1662 recommended minor changes to spelling, such as changing logique to logic, warre to war, sinne to sin, toune to town and tru to true.[6] Many of these spellings are now in general use.

From the 16th century AD onward, English writers who were scholars of Greek and Latin literature tried to link English words to their Graeco-Latin counterparts. They did this by adding silent letters to make the real or imagined links more obvious. Thus det became debt (to link it to Latin debitum), dout became doubt (to link it to Latin dubitare), sissors became scissors and sithe became scythe (as they were wrongly thought to come from Latin scindere), iland became island (as it was wrongly thought to come from Latin insula), ake became ache (as it was wrongly thought to come from Greek akhos), and so forth.[7][8]

William Shakespeare satirized the disparity between English spelling and pronunciation. In his play Love's Labour's Lost, the character Holofernes is "a pedant" who insists that pronunciation should change to match spelling, rather than simply changing spelling to match pronunciation. For example, Holofernes insists that everyone should pronounce the unhistorical B in words like doubt and debt.[9]

19th century

The second period started in the 19th century and appears to coincide with the development of phonetics as a science.[6] In 1806, Noah Webster published his first dictionary, A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language. It included an essay on the oddities of modern orthography and his proposals for reform. Many of the spellings he used, such as color and center, would become hallmarks of American English. In 1807, Webster began compiling an expanded dictionary. It was published in 1828 as An American Dictionary of the English Language. Although it drew some protest, the reformed spellings were gradually adopted throughout the United States.[10]

In 1837, Isaac Pitman published his system of phonetic shorthand, while in 1848 Alexander John Ellis published A Plea for Phonetic Spelling. These were proposals for a new phonetic alphabet. Although unsuccessful, they drew widespread interest.

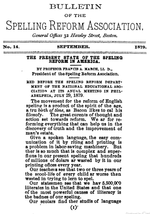

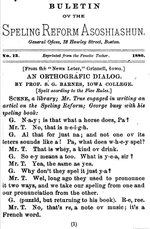

By the 1870s, the philological societies of Great Britain and America chose to consider the matter. After the "International Convention for the Amendment of English Orthography" that was held in Philadelphia in August 1876, societies were founded such as the English Spelling Reform Association and American Spelling Reform Association.[11] That year, the American Philological Society adopted a list of eleven reformed spellings for immediate use. These were are→ar, give→giv, have→hav, live→liv, though→tho, through→thru, guard→gard, catalogue→catalog, (in)definite→(in)definit, wished→wisht.[12][13] One major American newspaper that began using reformed spellings was the Chicago Tribune, whose editor and owner, Joseph Medill, sat on the Council of the Spelling Reform Association.[13] In 1883, the American Philological Society and American Philological Association worked together to produce 24 spelling reform rules, which were published that year. In 1898, the American National Education Association adopted its own list of 12 words to be used in all writings: tho, altho, thoro, thorofare, thru, thruout, catalog, decalog, demagog, pedagog, prolog, program.[14]

20th century onward

The Simplified Spelling Board was founded in the United States in 1906. The SSB's original 30 members consisted of authors, professors and dictionary editors. Andrew Carnegie, a founding member, supported the SSB with yearly bequests of more than US$300,000.[15] In April 1906, it published a list of 300 words,[16] which included 157[17] spellings that were already in common use in American English.[18] In August 1906, the SSB word list was adopted by Theodore Roosevelt, who ordered the Government Printing Office to start using them immediately. However, in December 1906, the U.S. Congress passed a resolution and the old spellings were reintroduced.[13] Nevertheless, some of the spellings survived and are commonly used in American English today, such as anaemia/anæmia→anemia and mould→mold. Others such as mixed→mixt and scythe→sithe did not survive.[19] In 1920, the SSB published its Handbook of Simplified Spelling, which set forth over 25 spelling reform rules. The handbook noted that every reformed spelling now in general use was originally the overt act of a lone writer, who was followed at first by a small minority. Thus, it encouraged people to "point the way" and "set the example" by using the reformed spellings whenever they could.[20] However, with its main source of funds cut off, the SSB disbanded later that year.

In Britain, the cause of spelling reform was promoted from 1908 by the Simplified Spelling Society and attracted a number of prominent supporters. One of these was George Bernard Shaw (author of Pygmalion) and much of his considerable will was left to the cause. Among members of the society, the conditions of his will gave rise to major disagreements, which hindered the development of a single new system.[21]

Between 1934 and 1975, the Chicago Tribune, then Chicago's biggest newspaper, used a number of reformed spellings. Over a two-month spell in 1934, it introduced 80 respelled words, including tho, thru, thoro, agast, burocrat, frate, harth, herse, iland, rime, staf and telegraf. A March 1934 editorial reported that two-thirds of readers preferred the reformed spellings. Another claimed that "prejudice and competition" was preventing dictionary makers from listing such spellings. Over the next 40 years, however, the newspaper gradually phased out the respelled words. Until the 1950s, Funk & Wagnalls dictionaries listed many reformed spellings, including the SSB's 300, alongside the conventional spellings.[13]

In 1949, a Labour MP, Dr Mont Follick, introduced a private member's bill in the House of Commons, which failed at the second reading. In 1953, he again had the opportunity, and this time it passed the second reading by 65 votes to 53.[22] Because of anticipated opposition from the House of Lords, the bill was withdrawn after assurances from the Minister of Education that research would be undertaken into improving spelling education. In 1961, this led to James Pitman's Initial Teaching Alphabet, introduced into many British schools in an attempt to improve child literacy.[23] Although it succeeded in its own terms, the advantages were lost when children transferred to conventional spelling. After several decades, the experiment was discontinued.

In his 1969 book Spelling Reform: A New Approach, the Australian linguist Harry Lindgren proposed a step-by-step reform. The first, Spelling Reform step 1 (SR1), called for the short /ɛ/ sound (as in bet) to always be spelled with <e> (for example friend→frend, head→hed). This reform had some popularity in Australia.[24]

In 2013, University of Oxford Professor of English Simon Horobin proposed that variety in spelling be acceptable. For example, he believes that it does not matter whether words such as "accommodate" and "tomorrow" are spelled with double letters.[25] Note that this proposal does not fit within the definition of spelling reform used by, for example, Random House Dictionary.[26]

Arguments for reform

It is argued that spelling reform would make it easier to learn to read (decode), to spell, and to pronounce, making it more useful for international communication, reducing educational budgets (reducing literacy teachers, remediation costs, and literacy programs) and/or enabling teachers and learners to spend more time on more important subjects or expanding subjects.

Advocates note that spelling reforms have taken place already,[27] just slowly and often not in an organized way. There are many words that were once spelled un-phonetically but have since been reformed. For example, music was spelled musick until the 1880s, and fantasy was spelled phantasy until the 1920s.[28] For a time, almost all words with the -or ending (such as error) were once spelled -our (errour), and almost all words with the -er ending (such as member) were once spelled -re (membre). In American spelling, most of them now use -or and -er, but in British spelling, only some have been reformed.

In the last 250 years, since Samuel Johnson prescribed how words ought to be spelled, pronunciations of hundreds of thousands of words (as extrapolated from Masha Bells' research on 7000 common words) have gradually changed, and the alphabetic principle that lies behind English (and every other alphabetically written language) has gradually been corrupted. Advocates argue that if we wish to keep English spelling regular, then spelling needs to be amended to account for the changes.

Ambiguity

Unlike many other languages, English spelling has never been systematically updated and thus today only partly holds to the alphabetic principle. As an outcome, English spelling is a system of weak rules with many exceptions and ambiguities.

Most phonemes in English can be spelled in more than one way. E.g. the words fear and peer contain the same sound in different spellings. Likewise, many graphemes in English have multiple pronunciations and decodings, such as ough in words like through, though, thought, thorough, tough, trough, plough, and cough. There are 13 ways of spelling the schwa (the most common of all phonemes in English), 12 ways to spell /ei/ and 11 ways to spell /ɛ/. These kinds of incoherences can be found throughout the English lexicon and they even vary between dialects. Masha Bell has analyzed 7000 common words and found that about 1/2 cause spelling and pronunciation difficulties and about 1/3, decoding difficulties. Improving English Spelling

Such ambiguity is particularly problematic in the case of heteronyms (homographs with different pronunciations that vary with meaning), such as bow, desert, live, read, tear, wind, and wound. In reading such words one must consider the context in which they are used, and this increases the difficulty of learning to read and pronounce English.

A closer relationship between phonemes and spellings would eliminate many exceptions and ambiguities and make the language easier and faster to master.[29]

Undoing the damage

Some proposed simplified spellings already exist as standard or variant spellings in old literature. As noted earlier, in the 16th century, some scholars of Greek and Latin literature tried to make English words look more like their Graeco-Latin counterparts, at times even erroneously. They did this by adding silent letters, so det became debt, dout became doubt, sithe became scythe, iland became island, ake became ache, and so on.[7][8] Some spelling reformers propose undoing these changes. Other examples of older spellings that are more phonetic include frend for friend (as on Shakespeare's grave), agenst for against, yeeld for yield, bild for build, cort for court, sted for stead, delite for delight, entise for entice, gost for ghost, harth for hearth, rime for rhyme, sum for some, tung for tongue, and many others. It was also once common to use -t for the ending -ed where it is pronounced as such (for example dropt for dropped). Some of the English language's most celebrated writers and poets have used these spellings and others proposed by today's spelling reformers. Edmund Spenser, for example, used spellings such as rize, wize and advize in his famous poem The Faerie Queene, published in the 1590s.[30]

Many English words are based on French modifications (e.g., colour and analogue) even though they come from Latin or Greek.

Redundant letters

The English alphabet has several letters whose characteristic sounds are already represented elsewhere in the alphabet. These include X, which can be realised as "ks", "gz", or z; soft G, which can be realised as J; hard C, which can be realised as K; soft C, which can be realised as S; and Q ("qu"), which can be realised as "kw", (or, simply, K in some cases). However, these spellings are usually retained to reflect their often-Latin roots.

Obstacles and criticisms

There are a number of barriers in the development and implementation of a reformed orthography for English:

- Public resistance to spelling reform has been consistently strong, at least since the early 19th century, when spelling was codified by the influential English dictionaries of Samuel Johnson (1755) and Noah Webster (1806).

- English vocabulary is mostly a melding of Germanic, French, Latin and Greek words, which have very different phonemes and approaches to spelling. Some reform proposals tend to favour one approach over the other, resulting in a large percentage of words that must change spelling to fit the new scheme.

- Some inflections are pronounced differently in different words. For example, plural -s and possessive -'s are both pronounced differently in cat(')s (/s/) and dog(')s (/z/). The handling of this particular difficulty distinguishes morphemic proposals, which tend to spell such inflectional endings the same, from phonemic proposals that spell the endings according to their pronunciation. These endings pose few issues in understanding the content (decoding and literacy). These differences in pronunciation are rule based Voice phonetics.

- English is the only one of the top ten major languages that lacks a worldwide regulatory body with the power to promulgate spelling changes. There is an English Spelling Society.

- The spellings of some words – such as tongue and stomach – are so unindicative of their pronunciation that changing the spelling would noticeably change the shape of the word. Likewise, the irregular spelling of very common words, such as is, are, have, done and of makes it difficult to fix them without introducing a noticeable change to the appearance of English text. This would create acceptance issues.

- Phonetic spelling reform could result in a multitude of different versions of written English, largely unintelligible across different accent-groups. Scottish writers might not be read by Indians. Americans would write whut and British wot for the same word.

- Spelling reform may make pre-reform writings harder to understand and read in their original form, often necessitating transcription and republication. Even today, few people choose to read old literature in the original spellings as most of it has been republished in modern spellings.[31]

Writing conveys meaning, not phonemes

The main criticism of many purely phonemic reform proposals is that written language is not a purely phonemic analog of the spoken word. While reformers might argue that the units of understanding are phonemes, critics argue that the basic units are words. Some of the most phonemic spelling reform proposals might re-spell closely related words less alike than they are spelled now, such as electric, electricity and electrician, or (with full vowel reform) photo, photograph and photography. This argument applies even more strongly to technical words that appear more often in writing than in speech, and to words that are similar to or identical to the corresponding words in other languages.

However, there are also a great number of words in the current lexicon that look like they are related in their orthography, but that are not semantically related at all. These words would be respelled differently and remove the ambiguity in such words as are and area, rein and reinvent, river and rival, ampersand and ampere, caterpillar and cater, ready and readjust, man and many, now and nowhere, etc. False-positives are bound to occur no matter what system is used.

Cognates in other languages

English is a West Germanic language that has borrowed many words from non-Germanic languages, and the spelling of a word often reflects its origin. This sometimes gives a clue as to the meaning of the word. Even if their pronunciation has strayed from the original pronunciation, the spelling is a record of the phoneme. The same is true for words of Germanic origin whose current spelling still resembles their cognates in other Germanic languages. Examples include light, German Licht; knight, German Knecht; ocean, French océan; occasion, French occasion. Critics argue that re-spelling such words could hide those links.[32]

Spelling reformers argue that, although some of these links may be hidden by a reform, others would become more noticeable. For example, Axel Wijk's 1959 proposal Regularised English proposed changing height to hight, which would link it more closely to the related word high.

In some cases, English spelling of foreign words has diverged from the current spellings of those words in the original languages, such as the spelling of connoisseur that is now spelled connaisseur in French after a French-language spelling reform in the 19th century.

The orthographies of other languages do not pay special attention to preserving similar links to loanwords. English loanwords in other languages are commonly assimilated to the orthographical conventions of those languages and so such words have a variety of spellings that are sometimes difficult to recognise as English words.

Accent differences

Another criticism is that a reform may favor one dialect or pronunciation over others, creating a standard language. Some words have more than one acceptable pronunciation, regardless of dialect (e.g. economic, either). Some distinctions in regional accents are still marked in spelling. Examples include the distinguishing of fern, fir and fur that is maintained in Irish and Scottish English or the distinction between toe and tow that is maintained in a few regional dialects in England and Wales.

Reformers point out that learners learn accents before they see any spelling.[33] Throughout their life, learners have a natural tendency to acquire and use the accent that they hear around them.[34] Later, as learners learn to read, they naturally use and assign the correct allophones or accent they have learned to the right phonemes or words, as is currently happening and has been for centuries, with a spelling system that is phonemically more accurate or not so much. Moreover, dialectal accents exist in languages whose spelling is called phonemic, such as Spanish. If a reform were to happen, learners will use the correct accent for the right letters or combinations of letters (words), whether the spelling is phonemic or not. A reform will simply make the match more intuitive, possibly more regular or systematic than is currently the case. A spelling reform would only affect how we spell words, not how we say them. After a reform, English would still allow multiple pronunciations of a standard spelling, as it is currently the case, with no one struggling to use the correct pronunciation for an ambiguous spelling. Some reformers also suggest that a reform could actually make spelling more inclusive of regional dialects by allowing more spellings for such words. Finally, other reformers would analyze the distribution of all of those dialectal phonemes and use a diaphoneme or an algorithm to create one unified system that would attempt to create one system that has some features of some dialects.

False friends

Some reform proposals try to make too many spelling changes at once and do not allow for any transitional period where the old spellings and the new may be in use together. The problem is an overlap in words, where a particular word could be an unreformed spelling of one word or a reformed spelling of another, akin to false friends when learning a foreign language.

For example, a reform could re-spell wonder as wunder and wander as wonder. However, both cannot be done at once because this causes ambiguity. During any transitional period, is wonder the unreformed spelling of wonder or the reformed spelling of wander? This could be resolved by using the old wander with the new wunder. Other similar chains of words are device → devise → *devize, warm → worm → *wurm and rice → rise → *rize.

Spelling reform proposals

Most spelling reforms attempt to improve phonemic representation, but some attempt genuine phonetic spelling, usually by changing the basic English alphabet or making a new one. All spelling reforms aim for greater regularity in spelling.

Using the basic English alphabet

Extending or replacing the basic English alphabet

These proposals seek to eliminate the extensive use of digraphs (such as "ch", "gh", "kn-", "-ng", "ph", "qu", "sh", voiced and voiceless "th", and "wh-") by introducing new letters and/or diacritics. Each letter would then represent a single sound. In a digraph, the two letters represent not their individual sounds but instead an entirely different and discrete sound, which can lengthen words and lead to mishaps in pronunciation.

Notable proposals include:

- Benjamin Franklin's phonetic alphabet

- Deseret alphabet

- Initial Teaching Alphabet

- Interspel

- Romic alphabet

- Shavian alphabet (revised version: Quikscript)

- SaypU (Spelling as you pronounce Universal)

- Unifon

- Simplified Standard Sound Symbols (S4)

- Simpel-Fonetik Method of Writing

Historical and contemporary advocates of reform

A number of respected and influential people have been active supporters of spelling reform.

- Orm/Orrmin, 12th century Augustine canon monk and eponymous author of the Ormulum, in which he stated that, since he dislikes the way that people are mispronouncing English, he will spell words exactly as they are pronounced, and describes a system whereby vowel length and value are indicated unambiguously. He distinguished short vowels from long by doubling the following consonants, or, where this is not feasible, by marking the short vowels with a superimposed breve accent.

- Thomas Smith, a Secretary of State to Queen Elizabeth I, who published his proposal De recta et emendata linguæ angliæ scriptione in 1568.[35]

- William Bullokar was a schoolmaster who published his book English Grammar in 1586, an early book on that topic. He published his proposal Booke at large for the Amendment of English Orthographie in 1580.[35]

- John Milton, poet.[36]

- John Wilkins, founder member and first secretary of the Royal Society, early proponent of decimalisation and a brother-in-law to Oliver Cromwell.

- Charles Butler, British naturalist and author of the first natural history of bees: Đe Feminin` Monarķi`, 1634. He proposed that 'men should write altogeđer according to đe sound now generally received,' and espoused a system in which the h in digraphs was replaced with bars.

- James Howell was a documented, successful (if modest) spelling reformer, recommending, in his Grammar of 1662, minor spelling changes, such as 'logique' to 'logic', 'warre' to 'war', 'sinne' to 'sin', 'toune' to 'town' and 'tru' to 'true',[6] many of which are now in general use.

- Benjamin Franklin, American innovator and revolutionary, added letters to the Roman alphabet for his own personal solution to the problem of English spelling.

- Samuel Johnson, poet, wit, essayist, biographer, critic and eccentric, broadly credited with the standardisation of English spelling into its pre-current form in his Dictionary of the English Language (1755).

- Noah Webster, author of the first important American dictionary, believed that Americans should adopt simpler spellings where available and recommended it in his 1806 A Compendious Dictionary of the English Language.

- Charles Dickens

- Isaac Pitman developed the most widely used system of shorthand, known now as Pitman Shorthand, first proposed in Stenographic Soundhand (1837).

- U.S. President Theodore Roosevelt commissioned a committee, the Columbia Spelling Board, to research and recommend simpler spellings and tried to require the U.S. government to adopt them;[37] however, his approach, to assume popular support by executive order,[37] rather than to garner it, was a likely factor in the limited change of the time.[38][39]

- Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson was a vice-president of the English Spelling Reform Association, precursor to the (Simplified) Spelling Society.

- Charles Darwin FRS, originator of the Theory of Evolution by Natural Selection, was also a vice-president of the English Spelling Reform Association, his involvement in the subject continued by his physicist grandson of the same name.

- John Lubbock, 1st Baron Avebury, close friend, neighbour and colleague of Charles Darwin, also involved in the Spelling Reform Association.

- H.G. Wells, science fiction writer and one-time Vice President of the London-based Simplified Spelling Society.

- Andrew Carnegie, celebrated philanthropist, donated to spelling reform societies on the US and Britain, and funded the Simplified Spelling Board.

- Daniel Jones, phonetician. professor of phonetics at University College London.

- George Bernard Shaw, playwright, willed part of his estate to fund the creation of a new alphabet now called the "Shavian alphabet".

- Mark Twain, a founding member of the Simplified Spelling Board.

- Robert Baden-Powell, 1st Baron Baden-Powell

- Upton Sinclair

- Melvil Dewey, inventor of the Dewey Decimal System, wrote published works in simplified spellings and even simplified his own name from Melville to Melvil.

- Israel Gollancz

- James Pitman, a publisher and Conservative Member of Parliament, grandson of Isaac Pitman, invented the Initial Teaching Alphabet.

- Charles Galton Darwin, KBE, MC, FRS, grandson of Charles Darwin and director of Britain's National Physical Laboratory (NPL) in World War II, was also a wartime vice-president of the Simplified Spelling Society.

- Mont Follick, Labour Member of Parliament, linguist (multi-lingual) and author who preceded Pitman in drawing the English spelling reform issue to the attention of Parliament. Favoured replacing w and y with u and i.

- Isaac Asimov[40]

- HRH Prince Philip, Duke of Edinburgh, one-time Patron of the Simplified Spelling Society. Stated that spelling reform should start outside of the UK, and that the lack of progress originates in the discord amongst reformers. However, his abandonment of the cause was coincident with literacy being no longer an issue for his own children, and his less than lukewarm involvement may have ended as a result of the Society's rejection of attempts to 'pull strings' behind the scenes.

- Robert R. McCormick (1880–1955), publisher of the Chicago Tribune, employed reformed spelling in his newspaper. The Tribune used simplified versions of some words, such as "altho" for "although".

- Edward Rondthaler (1905–2009), commercial actor, chairman of the American Literacy Council and vice-president of the Spelling Society.

- John C. Wells, London-based phonetician, Esperanto teacher and former professor of phonetics at University College London: past President of The English Spelling Society.

- Valerie Yule, a fellow of the Galton Institute, Vice-president of The English Spelling Society and founder of the Australian Centre for Social Innovations.

- Doug Everingham, doctor, former Australian Labor politician, health minister in the Whitlam government, and author of Chemical Shorthand for Organic Formulae (1943), and a proponent of the proposed SR1, which he used in ministerial correspondence.

- Allan Kiisk, professor of engineering, linguist (multi-lingual), author of Simple Phonetic English Spelling (2013) and Simpel-Fonetik Dictionary for International Version of Writing in English (2012).[41]

- Anatoly Liberman, professor in the Department of German, Scandinavian and Dutch at the University of Minnesota advocates spelling reforms at his weekly column on word origins at the Oxford University Press blog.[42] Current President of the English Spelling Society.[43]

- Masha Bell, writer and independent literacy researcher, retired teacher of English and modern languages.

See also

- History of the English language

- List of reforms of the English language

- Folk etymology

- Orthographies and dyslexia

- Phonemic orthography

- Phonological history of English

- The Phonetic Journal

- "The Chaos", a poem demonstrating the irregularity of English spelling

- Ghoti

References

- ↑ David Wolman, Righting the Mother Tongue: From Olde English to Email, the Tangled Story of English Spelling (HarperCollins, 2009).

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling. Simplified Spelling Board, 1920. p.3

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling, p.4

- ↑ Thomas Smith (1568), De recta & emendata lingvæ Anglicæ scriptione, dialogus: Thoma Smitho equestris ordinis Anglo authore [Correct and Improved English Writing, a Dialog: Thomas Smith, knight, English author], Paris: Ex officina Roberti Stephani typographi regij [from the office of Robert Stephan, the King's Printer], OCLC 20472303 .

- ↑ Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularized English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. pp. 17–18.

- 1 2 3 4 Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularized English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 18.

- 1 2 Handbook of Simplified Spelling, pp.5–7

- 1 2 Online Etymology Dictionary

- ↑ Horobin, Simon. Does Spelling Matter?. Oxford University Press, 2013. pp.113-114

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling, p.9

- ↑ Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularized English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 20.

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling, p.13

- 1 2 3 4 "Spelling Reform". Barnsdle.demon.co.uk. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling, p.14

- ↑ Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularized English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 21.

- ↑ "Simplified Spelling Board's 300 Spellings". Retrieved 12 July 2009.

- ↑ Wheeler, Benjamin (September 15, 1906). "Simplified Spelling: A Caveat (Being the commencement address delivered on September 15, 1906, before the graduating class of Stanford University)". London: B.H.Blackwell. p. 11. Missing or empty

|url=(help) - ↑ "Start the campaign for simple spelling" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 April 1906. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

- ↑ "Theodore Roosevelt's Spelling Reform Initiative: The List". Johnreilly.info. 1906-09-04. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- ↑ Handbook of Simplified Spelling, p.16

- ↑ Godfrey Dewey (1966), Oh, (P)shaw! (PDF)

- ↑ Alan Campbell, The 50th anniversary of the Simplified Spelling Bill, retrieved 2011-05-11

- ↑ Ronald A Threadgall, The Initial Teaching Alphabet: Proven Efficiency and Future Prospects, retrieved 2011-05-11

- ↑ Sampson, Geoffrey. Writing Systems. Stanford University Press, 1990. p.197.

- ↑ Taylor, Lesley Ciarula (30 May 2013). "Does proper spelling still matter?". Toronto Star. Retrieved 3 June 2013.

- ↑ "an attempt to change the spelling of English words to make it conform more closely to pronunciation." Spelling reform at dictionary.reference.com. Merriam-Webster dictionary has a similar definition.

- ↑ "Start the campaign for simple spelling" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 April 1906. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

[c]hange ... has been almost continuous in the history of English spelling.

- ↑ "English Language:Orthography". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 3 July 2009.

- ↑ Orthographies and dyslexia#cite note-:4-20

- ↑ Spenser, Edmund. The Faerie Queen (Book I, Canto III). Wikisource.

- ↑ "Start the campaign for simple spelling" (PDF). The New York Times. 1 April 1906. Retrieved 2009-07-12.

We do not print Shakespeare's or Bacon's words as they were written

- ↑ Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularised English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. pp. 63–64.

- ↑ Children As Young As 19 Months Understand Different Dialects

- ↑ Humans imitate aspects of speech we see

- 1 2 Wijk, Axel (1959). Regularized English. Stockholm: Almqvist & Wiksell. p. 17.

- ↑ "The Poetical Works of John Milton – Full Text Free Book (Part 1/11)". Fullbooks.com. Retrieved 2010-06-19.

- 1 2 "House Bars Spelling in President's Style" (PDF). New York Times. 1906-12-13. Retrieved 2007-12-17.

- ↑ John J. Reilly. "Theodore Roosevelt and Spelling Reform". Based on H.W. Brand's, T.R.: The Last Romantic, pp. 555-558

- ↑ Daniel R. MacGilvray (1986). "A Short History of GPO".

- ↑ Reilly, John (1999). "The Journal of the Simplified Spelling Society 1999". English Spelling Society. Archived from the original on 2005-09-23.

- ↑ Neeme, Urmas. "A Foreign Estonian Uses the Estonian Language for Guidance in Reforming the English Spelling". Simpel-Fonetik Spelling. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

- ↑ "Casting a last spell: After Skeat and Bradley". The Oxford Etymologist. OUP. Retrieved 9 August 2014.

- ↑ "Officers". The English Spelling Society. Retrieved 16 October 2015.

Further reading

- Bell, Masha (2004), Understanding English Spelling, Cambridge, Pegasus

- Bell, Masha (2012), SPELLING IT OUT: the problems and costs of English spelling, ebook

- Bell, Masha (2017), English Spelling Explained, Cambridge, Pegasus

- Children of the Code An extensive, in depth study of the illiteracy problem.

- Crystal, David. Spell It Out: The Curious, Enthralling and Extraordinary Story of English Spelling (St. Martin's Press, 2013)

- Hitchings, Henry. The language wars: a history of proper English (Macmillan, 2011)

- Kiisk, Allan (2013) Simple Phonetic English Spelling - Introduction to Simpel-Fonetik, the Single-Sound-per-Letter Writing Method, in printed, audio and e-book versions, Tate Publishing, Mustang, Oklahoma.

- Kiisk, Allan (2012) Simpel-Fonetik Dictionary - For International Version of Writing in English, Tate Publishing, Mustang, Oklahoma.

- Lynch, Jack. The Lexicographer's Dilemma: The Evolution of 'Proper' English, from Shakespeare to South Park (Bloomsbury Publishing USA, 2009)

- Marshall, David F. "The Reforming of English Spelling." Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The Success-Failure Continuum in Language and Ethnic Identity Efforts (2011) 2:113+

- Wolman, David. Righting the Mother Tongue: From Olde English to Email, the Tangled Story of English Spelling. HarperCollins, 2009. ISBN 978-0-06-136925-4.

External links

- "English accents and their implications for spelling reform", by J.C. Wells, University College London

- The OR-E system: Orthographic Reform of the English Language

- EnglishSpellingProblems blog by Masha Bell

- "Spelling reform: It didn't go so well in Germany" article in the Economist's Johnson Blog about spelling reform

- The Nooalf Revolution Provides an English-based international spelling system. The orthography has many similarities to Unifon.

- Wyrdplay.org has an extensive list of current spelling reform proposals.