Emilia Lanier

| Emilia Lanier | |

|---|---|

portrait by Nicholas Hilliard | |

| Born |

Aemilia Bassano 1569 Bishopsgate |

| Died |

1645 London, England |

| Movement | English Renaissance |

| Parent(s) | Baptiste Bassano; Margret Johnson |

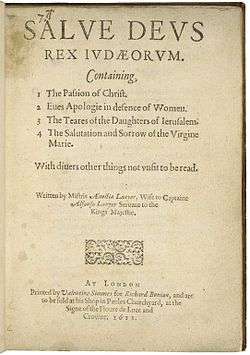

Emilia Lanier (also spelled Aemilia (or Amelia) Lanyer) (1569–1645), née Bassano, was a British poet in the early modern English era. She was the first Englishwoman to assert herself as a professional poet through her single volume of poems, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (1611).

Born Aemilia Bassano, Lanier was a member of the minor gentry through her father's appointment as a royal musician. She was further educated in the household of Susan Bertie, Countess of Kent. After her parent's death, Lanier was the mistress of Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon, first cousin of Elizabeth I of England. In 1592, she became pregnant by Carey and was subsequently married to court musician Alfonso Lanier, her cousin. She had two children, but only one survived into adulthood.

Lanier was often forgotten for centuries, but scholarship about her work has increased dramatically in recent decades.[1] She is now remembered for her contributions to English literature through her groundbreaking publishing of Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum. She is also noted as one of the first feminist writers in England as well as the potential "dark lady" of Shakespearean myth. Lanier's story has recently been reimagined in a new play by Morgan Lloyd Malcolm titled Emilia; the production was first staged at Shakespeare's Globe Theatre on 10 August 2018.[2]

Biography

Emilia Lanier's life is well documented through her letters, poetry, medical records, legal records, and through sources about the social contexts in which she lived.[3] Researchers have used entries in astrologer Dr. Simon Forman's (1552–1611) professional diary, the first casebook kept by an English medical practitioner, which logs interactions with Lanier. Lanier visited Forman many times during 1597 for consultations that incorporated astrological readings, as was usual for the period. As seems to have been the case with many of his patients, Forman attempted to seduce Lanier during their meetings. Lanier refused the astrologer's advances; Forman's documentation of their meetings subsequently became unfairly critical of Lanier. Forman's embittered representation of Lanier's character skewed how the poet has been remembered.

Early life

Church records show that Lanier was baptised Aemilia Bassano at the parish church of St. Botolph, Bishopsgate, on 27 January 1569. Her father, Baptiste Bassano, was a Venice-born musician at the court of Elizabeth I. Her mother was Margret Johnson (born ca. 1545–1550), possibly the aunt of court composer Robert Johnson. Lanier had a sister, Angela Bassano, who married Joseph Hollande in 1576. Lanier also had two brothers, Lewes and Phillip, both of whom died before they reached adulthood.[4] It has been suggested that Lanier's family was Jewish or of partial Jewish descent, though this is disputed. Susanne Woods argues that evidence for Lanier's Jewish heritage is, "circumstantial but cumulatively possible".[5] Leeds Barroll says Lanier was "probably a Jew", her baptism being, "part of the vexed context of Jewish assimilation in Tudor England."[6]

Baptiste Bassano died on April 11 1576, when Aemilia was seven years old. Bassano's will dictated to his wife that he had left young Aemilia a dowry of £100, to be given to her when she turned twenty-one years old or on the day of her wedding, whichever came first. Forman's records indicate that Bassano's fortune might have been waning before he died which caused considerable unhappiness.[7]:xv–xvii

Foreman's records also indicate that, after the death of her father, Lanier went to live with Susan Bertie, Countess of Kent. Some scholars question whether Lanier went to serve Bertie or be fostered by her, but there is no conclusive evidence to confirms either. It was in Bertie's house that Lanier was given a humanist education and learned Latin. Bertie greatly valued and emphasized the importance of young girls receiving the same level of education as young men.[4] This decision likely impacted Lanier and her own decision to publish her writing. After living with Bertie, Lanier went to live with Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland, and Margaret's daughter, Lady Anne Clifford. Dedications in Lanier's own poetry seem to confirm this information.[8]

Lanier's mother died when Lanier was eighteen. Church records show that Johnson was buried in Bishopsgate on July 7 1587.[8]

Adulthood

Not long after her mother's death, Lanier became the mistress of Tudor courtier and cousin of Queen Elizabeth I, Henry Carey, 1st Baron Hunsdon. At the time of their affair, Lord Hunsdon was Elizabeth's Lord Chamberlain and a patron of the arts and theatre. Carey was forty-five years older than Lanier, and records indicate that Carey gave her a pension of £40 a year. Records indicate that Lanier appeared to have enjoyed her time as Carey's mistress. An entry from Forman's diary reads, "[Lanier] hath bin married 4 years/ The old Lord Chamberlain kept her longue She was maintained in great pomp ... she hath 40£ a yere & was welthy to him that married her in monie & Jewells".[7]:xviii

In 1592, when she was twenty-three, Lanier became pregnant with Carey's child. Carey paid her off with a sum of money. Lanier was then married to her first cousin once removed, Alfonso Lanier. He was a Queen's musician, and church records show the two were married in St. Botolph's church, Aldgate, on October 18 1592.[4]

Forman's diary entries implies that Lanier's marriage was an unhappy one. The entry also relates that Lanier was much happier as Carey's mistress than Alfonso's bride. It reads, "... and a nobleman that is ded hath Loved her well & kept her and did maintain her longe but her husband hath delte hardly with her and spent and consumed her goods and she is nowe ... in debt".[7]:xviii Another of Forman's diary entries states that Lanier told him about having several miscarriages. Lanier did gave birth to a son, Henry, in 1593 (presumably named after his father, Henry Carey) and a daughter, Odillya, in 1598. Odillya died when she was ten months old and was buried at St. Botolph's, Bishopsgate.

In 1611, Lanier published her volume of poetry, Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum. Lanier was forty-two years old at the time, and she was the first woman in England to declare herself a poet. People who read her poetry considered it very radical, and many scholars today refer to its style and arguments as "proto-feminist".[4]

Elder years

Alfonso and Aemilia remained married until his death in 1613. After Alfonso's death, Lanier supported herself by running a school. She rented a house from Edward Smith to house her students but, due to disputes over the correct rent price, was arrested on two different occasions between 1617 and 1619. Because parents weren't willing to send their children to a woman with a history of arrest, Lanier's dreams of running a prosperous school ended.[9]

Lanier's son eventually married Joyce Mansfield in 1623; they had two children, Mary (1627) and Henry (1630). Henry senior died in October 1633. Later court documents imply that Lanier may have been providing for her two grandchildren after their father's death.[4]

Little else is known about Lanier's life between 1619 and 1635. Court documents state that Lanier brought a lawsuit against her husband's brother, Clement, for money owed to her from the profits of one of her late husband's financial patents. The court ruled in Lanier's favor, declaring that Clement pay her £20. Clement couldn't pay her immediately, so Lanier brought the suit to court again in 1636 and in 1638. There are no records that verify whether Lanier was ever paid in full but, at the time of her death, she was described as a "pensioner," someone who has a steady income or pension.[9]

Lanier died at the age of seventy-six and was buried at Clerkenwell, on April 3 1645.[9]

Poetry

At the age of forty-two, in 1611, Lanier published a collection of poetry called Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum (Hail, God, King of the Jews). At the time of publication, it was extremely unusual for an Englishwoman to publish, especially as an attempt to make a living. Emilia was only the fourth British woman to publish poetry. Previously, the English poet Isabella Whitney had published a 38-page pamphlet of poetry partly written by her correspondents, Anne Dowriche, who was Cornish, and Elizabeth Melville, who was Scottish. Therefore, Lanier's book is the first book of substantial, original poetry written by an Englishwoman, and she wrote it hoping to attract a patron. It was also potentially the first feminist work published in England because all of the dedications are for women, and the "Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum" (a poem about the crucifixion of Christ) is written from a woman's perspective.[10].

Influences

Source analysis shows that Lanier draws on the books that she mentions reading, including Edmund Spenser, Ovid, Petrarch, Chaucer, Boccaccio, Agrippa, as well as books by feminists like Veronica Franco[11] and Christine de Pizan.[12] Lanier makes use of two unpublished manuscripts and a published a play translation by Mary Sidney, Countess of Pembroke. She also shows a knowledge of theatrical plays by John Lyly, Samuel Daniel, the unpublished manuscript of Shakespeare's Antony and Cleopatra[13] and the allegorical meanings of the Pyramus and Thisbe scene in A Midsummer Night's Dream which were only rediscovered in 2014.[14]:192 The work of Samuel Daniel informs her Masque, a theatrical form which has been identified in her letter to Mary Sidney and which resembles the Masque in The Tempest.[15]

Poems

The title poem, "Salve Deus Rex Judæorum," is prefaced by ten shorter dedicated poems, all for aristocratic women, beginning with the queen. There is also a prose preface addressed to the reader, comprising a vindication of "virtuous women" against detractors of the sex. The title poem, a long narrative work of over 200 stanzas, tells the story of Christ's passion satirically and almost entirely from the point of view of the women who surround him. The title comes from the words of mockery supposedly addressed to Jesus on the cross. The satirical nature of the poem was first identified by Boyd Berry.[16] Although the topics of virtue and religion were considered suitable themes for women writers, Lanier's title poem has been viewed by some modern scholars as a parody of the crucifixion. This argument is made because Lanier uses imagery of the Elizabethan grotesque,[17] found, for instance, in some of the Shakespearean plays, to mock the crucifixion. The views expressed in the poem have been interpreted as "independent of church tradition" and utterly heretical,[18] though other scholars like A.L. Rowse view Lanier's conversion as genuine and her passionate devotion to Christ and to his mother as sincere. Still, comparisons have been made between Lanier's poem and religious satires that scholars have studied in Shakespearean works, including the poem The Phoenix and the Turtle[19] and in many of the plays.

In the central section of Salve Deus Lanier takes up the Querrelle des Femmes[20] by redefining the Christian doctrine of 'The Fall', and attacking Original Sin, which is the foundation of Christian theology and Pauline doctrine about women causing human sin. Lanier defends Eve, and womankind in general, arguing that Eve is wrongly blamed for the Original Sin, and no blame is ever placed on Adam. She argues in the poem that Adam shares the guilt because Adam is depicted as being stronger than Eve in the Bible. Therefore, he should have been able to resist the temptation. She also defends women by highlighting the dedication of the female followers of Christ who stayed with him throughout the crucifixion and looked for him first after the burial and resurrection.

In Salve Deus, Lanier also draws attention to Pilate's wife, a minor character in the Bible, who attempted to intervene and prevent the unjust trial and crucifixion of Christ.[21] She also notes the male apostles that forsook and even denied Christ during His crucifixion. Lanier repeats the anti-Semitic aspects of the Gospel accounts, including hostile attitudes towards the Jews for not having prevented the crucifixion; these views are the norm for her period.

There is no clear consensus by scholars on the religious motivation of the title poem. Some maintain that it is a genuinely religious poem from a strong, female perspective. Others have suggested that it is a piece of clever satire. Although there is no agreement on intent and motive, most scholars do note the strong feminist sentiments throughout the entire Salve Deus Rex Judæorum.

Lanier's book ends with the "Description of Cookham," commemorating Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland and her daughter Lady Anne Clifford. This is the first published country house poem in English (Ben Jonson's more famous "To Penshurst" may have been written earlier but was first published in 1616). Lanier's inspiration came from her stay at Cookham Dean, where Margaret Clifford, Countess of Cumberland, lived with her daughter Lady Anne Clifford, for whom Lanier was engaged as a tutor and companion. The Clifford household was notable for its library, some of which can be identified in the painting The Great Picture, attributed to Jan van Belcamp.[22] As scholar Helen Wilcox asserts, the poem is an allegory of the expulsion from Eden.[23]

Feminist themes

Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum has been viewed by many critics to be one of the earliest feminist works of British literature. Barbara Kiefer Lewalski in her article, "Writing Women and Reading the Renaissance," actually calls Lanier the "defender of womankind"[24] Lewalski claims that with the first few poems of the collection, as dedications to prominent women, Lanier is initiating her ideas of the genealogy of women.[25] The genealogy follows the idea that, "virtue and learning descend from mothers to daughters".[26]

Marie H. Loughlin continues Lewalski's argument writing, "'Fast ti'd unto Them in a Golden Chaine': Typology, Apocalypse, and Woman's Genealogy in Aemilia Lanier's Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum," by noting that the genealogy of women began with Eve. Loughlin claims that Lanier is advocating the importance of knowledge of both the spiritual and material worlds in connection with women.[27] Lanier seems to argue that women must focus on the material world and their importance in it to supplement their life in the spiritual world rather than focusing solely on the spiritual.[28] This argument stems from, what seems to be, Lanier's desire to raise women up to the same level as men.

Dark Lady theory

The Sonnets

Some have speculated that Lanier, noted as a striking woman, was Shakespeare's "Dark Lady". This identification was first proposed by A. L. Rowse and has been repeated by several authors since. The Dark Lady speculation is written about notably by David Lasocki and Roger Prior in their 1995 book The Bassanos: Venetian Musicians and Instrument makers in England 1531–1665 and by Stephanie Hopkins Hughes. Although the color of Lanier's hair is not known, records exist in which her Bassano cousins were referred to as "black," a common term at that time for brunettes or persons with Mediterranean coloring. Since she came from a family of Court musicians, she fits Shakespeare's picture of a woman playing the virginal in Sonnet 128. Shakespeare claims that the woman was "forsworn" to another in Sonnet 152 which has been speculated to refer to Lanier's relationship with Shakespeare's patron, Lord Hunsdon. The theory that Lanier was the Dark Lady is doubted by other Lanier scholars like Susanne Woods (1999). Barbara Lewalski notes that Rowse's theory that Lanier was Shakespeare's "Dark Lady" has deflected attention from Lanier as a poet. However, Martin Green has argued that, although Rowse's argument was unfounded, he was correct that Lanier is referred to in the Sonnets.[29] John Hudson has argued that Lanier is the author of some or all of the works of Shakespeare, and her references to the "Dark Lady" should be interpreted as self-referential or autobiographical.[30]

Apart from the scholarly research, playwrights, musicians and poets have also expressed views. The theater historian and playwright Professor Andrew B. Harris has written a play The Lady Revealed which chronicles Rowse's identification of Lanier as the 'Dark Lady'. After readings in London and at the Players' Club, it received a staged reading at New Dramatists in New York City on 16 March 2015.[31] In 2005[32] the English conductor Peter Bassano, a descendant of Emilia, suggested that she provided some of the texts for William Byrd's 1589 Songs of Sundrie Natures dedicated to Lord Hunsdon. He further suggested that one of the songs, the setting of the translation of an Italian sonnet: Of Gold all Burnisht may have been used by Shakespeare as the model for his parodic Sonnet 130: My mistress' eyes are nothing like the sun. Irish poet Niall McDevitt believes Lanier was the Dark Lady, saying "She spurned his advances somewhere along the line and he never won her back ... It's a genuine story of unrequited love."[33]

Tony Haygarth has argued that a particular miniature portrait by Nicholas Hilliard, 1593, depicts Lanier.[34]

Plays

John Hudson points out that the names Emilia in Othello and Bassanio in The Merchant of Venice each coincide with a mention of a swan dying to music, which he claims is a standard Ovidian image of a great poet.[35] Hudson asserts that the "swan song" might be a literary device, used in some classical writings, to conceal the name of the author of a literary work. However, the notion that a dying swan sings a melodious "swan song" was proverbial, and its application to a character need not prove the character is being presented as a poet. Therefore, the evidence remains inconclusive and perhaps coincidental.

Furthermore, Prior argues that the play Othello refers to a location in the town of Bassano, and that the title of the play might refer to the Jesuit Girolamo Otello from the town of Bassano.[36] The character Emilia speaks some of the first feminist lines on an English stage and could thus be seen as a contemporary allegory for Emilia Lanier herself, while the musicians in both plays, Prior argues, are allegories for members of her family. For these and other reasons it has been argued by Prior and other scholars that Lanier co-authored these plays, especially the 1623 First Folio version of Othello which contains 163 key lines not present in the 1622 Quarto.

In addition, Hudson believes that another "signature" exists in Titus Andronicus where there are an Aemilius and a Bassianus, each holding a crown. Each of these mirrors the other's position at the beginning and end of the play as rhetorical markers indicating that the two names are a pair, and book-end the bulk of the play.[14]:163, 230 For reasons such as these, it is speculated that Emilia Bassano Lanier is one of twelve leading candidates for authorship of the plays and poems attributed to William Shakespeare.[37] Other scholarly sources refute this claim.

See also

Notes

- ↑ Chedgzoy, Kate (2010). "Remembering Aemilia Lanyer". Journal of the Northern Renaissance. 1 (1): 1. Retrieved 9 April 2018.

- ↑ http://www.shakespearesglobe.com/whats-on-2018/emilia

- ↑ Woods, Susanne (1993). The Poems of Aemilia Lanyer Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. xxiii. ISBN 0-19-508361-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 McBride, Kari Boyd (2008) Web Page Dedicated to Aemilia Lanyer Archived 25 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine., accessed on 1 May 2015

- ↑ Woods, Susanne (1999) Lanyer: A Renaissance Woman Poet, p. 180, Oxford: Oxford University Press ISBN 978-0-19-512484-2

- ↑ Barroll, Leeds, "Looking for Patrons" in Marshall Grossman (ed) (1998) Aemilia Lanyer: Gender, Genre, and the Canon, pp. 29, 44, University Press of Kentucky ISBN 978-0-8131-2049-2

- 1 2 3 Susanne Woods, Ed. (1993) The Poems of Aemilia Lanyer, Oxford University Press, New York, NY ISBN 978-0-19-508361-3

- 1 2 McBride, Biography of Aemilia Lanyer, 1

- 1 2 3 McBride, Biography of Aemilia Lanyer, 3

- ↑ "Æmilia Lanyer" PoetryFoundation.org

- ↑ Dana Eatman Lawrence, Class, Authority, and The Querelle Des Femmes: A Women's Community of Resistance in Early Modern Europe. Ph.D. thesis (Texas: Texas A&M University, 2009) 195

- ↑ In a Cristina Malcolmson paper, 'Early Modern Women Writers and the Gender Debate: Did Aemilia Lanyer Read Christine de Pisan?', she presented at the Centre for English Studies, University of London, n.d..

- ↑ Charles Whitney (2006) Early Responses to Renaissance Drama, p. 205, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press ISBN 978-0-521-85843-4

- 1 2 John Hudson (2014) Shakespeare's Dark Lady: Amelia Bassano Lanier: The Woman Behind Shakespeare's Plays?, Stroud: Amberley Publishing ISBN 978-1-4456-2160-9

- ↑ Melanie Faith, "The Epic Structure and Subversive Messages of Aemilia Lanyer's Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum." M.A. thesis (Blacksburg, Virginia: Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University, 1998).

- ↑ Boyd Berry, '"Pardon though I have digrest": Digression as a style in Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum', in M. Grossman (ed.), Aemilia Lanyer; Gender, Genre and the Canon (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press, 1998)

- ↑ Nel Rhodes, Elizabethan Grotesque (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980)

- ↑ Achsah Guibbory, "The Gospel According to Aemilia: Women and the Sacred", in Marshall Grossman (ed.) (1998) Aemelia Lanyer: Gender, Genre and the Canon (Lexington: University of Kentucky Press)

- ↑ James P. Bednarz (2012) Shakespeare and the Truth of Love; The Mystery of "The Phoenix and the Turtle", New York: Palgrave Macmillan ISBN 978-0-230-31940-0

- ↑ The woman question

- ↑ Mathew 27:19 Biblehub.com

- ↑ The Great Picture (1646)

- ↑ Helen Wilcox (2014) 1611: Authority, Gender, and the Word in Early Modern England, pp. 55–56 (Chichester: Wiley)

- ↑ Lewalski, Barbara Keifer. "Writing Women and Reading the Renaissance." Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. 4 (Winter, 1991), pp. 792–821.

- ↑ Lewalski 802–803

- ↑ Lewalski 803

- ↑ Loughlin, Marie H. (Spring, 2000) "'Fast ti'd unto Them in a Golden Chaine': Typology, Apocalypse, and Woman's Genealogy in Aemilia Lanyer's Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum", Renaissance Quarterly, Vol. 53, No. 1, pp. 133–179

- ↑ Loughlin 139

- ↑ Martin Green 'Emilia Lanier IS the Dark Lady of the Sonnets' English Studies, 87,5 (2006) 544-576.

- ↑ John Hudson, Shakespeare's Dark Lady: Amelia Bassano Lanier: The Woman Behind Shakespeare's Plays? (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2014).

- ↑ "The Lady Revealed; A Play Based on the Life and Writings of A.L. Rowse by Dr. Andrew B. Harris"

- ↑ Duke University, International William Byrd Conference 17–19 November 2005

- ↑ "Conjure the Bard: On London's streets, Nigel Richardson follows a latter-day Prospero bringing William Shakespeare back to life" (February 26, 2011) Sydney Morning Herald

- ↑ Simon Tait (7 December 2003) "Unmasked- the identity of Shakespeare's Dark Lady", The Independent

- ↑ John Hudson (10 February 2014) "A New Approach to Othello; Shakespeare's Dark Lady", HowlRound

- ↑ E. A, J. Honigmann (ed) Othello, Arden Shakespeare 3rd edition (London: 1999) 334

- ↑ Shakespeare Authorship Trust. "Candidates". Retrieved March 18, 2016.

References

- David Bevington, Aemilia Lanyer: Gender, Genre, and the Canon. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky (1998).

- John Garrison, 'Aemilia Lanyer's Salve Deus Rex Judaeorum and the Production of Possibility.' Studies in Philology, 109.3 (2012) 290-310.

- Martin Green, 'Emilia Lanier IS the Dark Lady' English Studies vol. 87, No.5, October (2006), 544-576.

- John Hudson, Shakespeare's Dark Lady: Amelia Bassano Lanier: The Woman Behind Shakespeare's Plays? (Stroud: Amberley Publishing, 2014).

- John Hudson, 'Amelia Bassano Lanier: A New Paradigm', The Oxfordian 11 (2008): 65–82.

- Stephanie Hopkins Hughes, 'New Light on the Dark Lady' Shakespeare Oxford Newsletter, 22 September (2000).

- David Lasocki and Roger Prior, The Bassanos: Venetian Musicians and Instrument makers in England 1531–1665 (Aldershot: Scolar Press, 1995).

- Peter Matthews, Shakespeare Exhumed: The Bassano Chronicles, Stanthorpe: Bassano Publishing, 2013.

- Ted Merwin, 'The Dark Lady as a Bright Literary Light' The Jewish Week, 23 March (2007) 56-7.

- Giulio M. Ongaro 'New Documents on the Bassano Family' Early Music vol. 20, 3 August (1992) 409–413.

- Michael Posner, 'Rethinking Shakespeare' The Queen's Quarterly, vol. 115, no. 2 (2008) 1–15.

- Michael Posner, 'Unmasking Shakespeare', Reform Judaism Magazine, 2010.

- Roger Prior, 'Jewish Musicians at the Tudor Court' The Musical Quarterly, vol. 69, no 2 .Spring, (1983), 253–265.

- Roger Prior, 'Shakespeare's Visit to Italy', Journal of Anglo-Italian Studies 9 (2008) 1–31.

- Michelle Powell-Smith, 'Aemilia Lanyer: Redeeming Women Through Faith and Poetry,' 11 April 2000 on-line at Suite101.

- Roger Prior 'Jewish Musicians at the Tudor Court' The Musical Quarterly, vol. 69, no 2 .Spring, (1983), 253–265.

- Ruffati and Zorattini, 'La Famiglia Piva-Bassano Nei Document Degli Archevi Di Bassano Del Grappa,' Musica e Storia. 2 December 1998.

- Julia Wallace, 'That's Miss Shakespeare To You' Village Voice, 28 March – 3 April (2007) pg 42.

- Steve Weitzenkorn, Shakespeare's Conspirator: The Woman, The Writer, The Clues, CreateSpace, 2015.

- Susanne Woods, Lanyer: A Renaissance Woman Poet. New York: Oxford University Press (1999).

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Emilia Lanier |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Emilia Lanier |

- Full text of Salve Deus Rex Iudæorum

- Discussion of the identification of Lanier as the Dark Lady

- John Hudson's thesis, that Lanier was the author of Shakespeare's plays

- Project Continua: Biography of Aemilia Lanyer

- Shakespeare/Lanier walk

- Works by Emilia Lanier at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)