Electrophilic aromatic directing groups

In organic chemistry, an electron donating group (EDG) or electron releasing group (ERG) (+I effect) is an atom or functional group that donates some of its electron density into a conjugated π system via resonance or inductive effects, thus making the π system more nucleophilic.[1][2] When attached to a benzene molecule, an electron donating group makes it more likely to participate in electrophilic substitution reactions. Benzene itself will normally undergo substitutions by electrophiles, but additional substituents can alter the reaction rate or products by electronically or sterically affecting the interaction of the two reactants. EDGs are often known as activating groups.

An electron withdrawing group (EWG) (-I effect) will have the opposite effect on nucleophilicity as an EDG, as it removes electron density from a π system, making the π system more electrophilic.[2][3] When attached to a benzene molecule an electron withdrawing group makes electrophilic aromatic substitution reactions slower and more complex, and EWGs are often called deactivating groups. Depending on their relative strengths, EWGs also determine the positions (relative to themselves) on the benzene ring where substitutions must take place; this property is therefore important in processes of organic synthesis.

Electron donating groups are generally ortho/para directors for electrophilic aromatic substitutions, while electron withdrawing groups are generally meta directors with the exception of the halogens which are also ortho/para directors as they have lone pairs of electrons that are shared with the aromatic ring.

Categories

Electron donating groups are typically divided into three levels of activating ability. Electron withdrawing groups are assigned to similar groupings. Activating substituents favor electrophilic substitution about the ortho and para positions. Weakly deactivating groups direct electrophiles to attack the benzene molecule at the ortho- and para- positions, while strongly and moderately deactivating groups direct attacks to the meta- position.[4] This is not a case of favoring the meta- position like para- and ortho- directing functional groups, but rather disfavoring the para- and ortho- positions more than they disfavor the meta- position.

Electron Donating groups

| Magnitude of

the EDG effect |

Substituent Name | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | phenoxide | -O− |

| tertiary amines | -NR2 | |

| secondary amines | -NHR | |

| primary amine | -NH2 | |

| ethers | -OR | |

| phenol | -OH | |

| Moderate | amides | -NHCOR |

| esters | -OCOR | |

| Weak | alkyl (e.g. -CH3, -C2H5) | -(CH2)nCH3 |

| phenyl | -C6H5 | |

| vinyl | -CH=CH2 |

Electron Withdrawing groups

Halides are ortho- para- directing groups but unlike most ortho- para- directors, halides tend to deactivate benzene. This unusual behavior can be explained by two properties:

- Since the halogens are very electronegative they cause inductive withdrawal (withdrawal of electrons from the carbon atom of benzene).

- Since the halogens have non-bonding electrons they can donate electron density through pi bonding (resonance donation).

The inductive and resonance properties compete with each other but the resonance effect dominates for purposes of directing the sites of reactivity. Fluorine directs strongly to the para position (86%) while Iodine directs to ortho and para (45% and 54% respectively).

| Magnitude of

the EWG effect |

Substituent Name | Structure |

|---|---|---|

| Strong | Triflyl | -SO2CF3 |

| trihalides | -CF3, -CCl3 | |

| cyano groups | -C≡N | |

| sulfonates | -SO3H | |

| nitro group | -NO2 | |

| ammonium | -NH3+ | |

| ammonium (quaternary amine) | -NR3+ | |

| Moderate | aldehyde | -CHO |

| ketones | -COR | |

| carboxylic acid | -COOH | |

| acyl chloride | -COCl | |

| esters (benzoate) | -COOR | |

| amide | -CONH2 | |

| Weak | halides | -F, -Cl, -Br, -I |

Mechanism

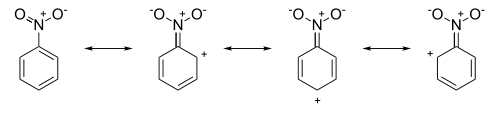

While steric effects are a consideration, the major contribution of EWGs is achieved by utilizing the nature of conjugated systems (specifically the ease through which mesomeric effects travel through such systems) to create regions of positive charge within the resonance contributors. For example, in nitrobenzene the resonance structures have positive charges around the ring system:

The resulting resonance hybrid, now possessing formal positive charges in the ortho- and para- positions repels approaching electrophiles increasing the relative success of attack in the meta position.

The selectivities observed with EDGs and EWGs were first described in 1892 and have been known as the Crum Brown–Gibson rule.[5]

Fluorine revisited (and the other halogens too)

Fluorine is something of an anomaly in this circumstance. Above, it is described as a weak electron withdrawing group but this is only partly true. It is correct that fluorine has a -I effect, which results in electrons being withdrawn inductively. However, another effect that plays a role is the +M effect which adds electron density back into the benzene ring (thus having the opposite effect of the -I effect but by a different mechanism). This is called the mesomeric effect (hence +M) and the result for fluorine is that the + M effect approximately cancels out the -I effect. The effect of this for fluoro-benzene is that its reactivity is comparable to that of benzene and its different properties can be attributed to the change in inter-molecular forces between the fluro-benzene molecules.

This -I and +M effect is true for all halides - there is some electron withdrawing and donating character of each. To understand why the reactivity changes occur, we need to consider the orbital overlaps occurring in each. The valence orbitals of fluorine are the 2p orbitals which is the same for carbon - hence they will be very close in energy and orbital overlap will be favourable. Chlorine has 3p valence orbitals, hence the orbital energies will be further apart, leading to less favourable bonding and a weaker interaction, hence chloro-benzene is more reactive than fluoro-benzene. This orbital overlap can be used to explain the energies and reactivities of a variety of different molecules.

See also

References

- ↑ "Electron withdrawing group". Illustrated Glossary of Organic Chemistry. UCLA Department of Chemistry. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- 1 2 Hunt, Ian. "Substituent Effects". University of Calgary Department of Chemistry. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "Electron donating group". Illustrated Glossary of Organic Chemistry. UCLA Department of Chemistry. Retrieved 16 November 2012.

- ↑ "Substituent Effects". www.mhhe.com. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ↑ Crum Brown, A.; Gibson, J. (1892). "XXX.—A rule for determining whether a given benzene mono-derivative shall give a meta-di-derivative or a mixture of ortho- and para-di-derivatives". J. Chem. Soc. 61: 367–369. doi:10.1039/ct8926100367.