Draft lottery (1969)

On 1 December 1969 the Selective Service System of the United States conducted two lotteries to determine the order of call to military service in the Vietnam War for men born from 1 January 1944 to 31 December 1950. These lotteries occurred during a period of conscription in the United States that lasted from 1947 to 1973. It was the first time a lottery system had been used to select men for military service since 1942.

Origins

The reason for the lottery of 1969 was to address perceived inequities in the draft system as it existed previously, and to add more military personnel towards the Vietnam War. After World War II, Japan left Vietnamese Emperor Bao Dai as the head of the country. Ho Chi Minh, another Vietnamese leader who was communist and sought immediate independence for the entirety of Vietnam, saw this as an opportunity to strike (knowing that Bao Dai had little support from the general population as he was widely regarded as a Japanese-installed puppet) and successfully took over Hanoi and most of northern Vietnam. Ho Chi Minh then set up the Democratic Republic of Vietnam (or North Vietnam) by the beginning of 1946. Emperor Bao Dai, still in power in the southern half of the country, set up the State of Vietnam, with support from the returning French colonial rulers, with Saigon as its capital. Ho Chi Minh based his political structure and government on other communist states such as the Soviet Union, while Emperor Bao Dai wanted a Vietnam that was modelled after the West, like the United States,[1] with a democratic government.

Both Ho's Democratic Republic of Vietnam (with support from the Soviet Union and China) and Bao Dai's State of Vietnam (with support from France) began open armed conflict against one another until the battle of Dien Bien Phu in 1954 ended with the communist Viet Minh forces as the victor over the French. Afterwards, at the Geneva Conference, Vietnam was split along the 17th Parallel north, and it was intended that a nationwide reunification election be held in 1956 to determine which side would take over all of Vietnam. Ngo Dinh Diem deposed Emperor Bao Dai in 1955 and took over leadership of the State of Vietnam (now known as the Republic of Vietnam, or South Vietnam) Diem, a Catholic, disliked Buddhists and took a very harsh stance against communism. He was opposed to reconciliation with the North and against the elections of 1956.[1][1]

In other parts of the world, the Cold War was intensifying between the Soviet Union and the United States. The U.S. was becoming more rigid in its policies towards the communist allies of the Soviet Union. President Dwight D. Eisenhower started supporting the South Vietnamese who were also against the communist north.[1]

The U.S. began training and equipping Diem's forces with weapons. Conflicts between communist sympathizers began occurring in the South. At the time, the U.S. had only committed around 800 personnel to train and outfit the South Vietnamese. In 1961, the John F. Kennedy administration started working under the "Domino Theory," which stated that if South Vietnam was to fall to the North, then other places in southeast Asia were to become vulnerable to communism as well. This caused President Kennedy to begin sending additional American soldiers to Vietnam. By 1962, there were around 9,000 personnel in Vietnam.[1]

In 1963, a coup was organized by South Vietnamese generals which resulted in the death of Diem. President Lyndon B. Johnson increased the number of U.S. personnel in South Vietnam due to the political instability in the country. In August 1964, two U.S. warships were attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. Johnson condemned North Vietnam, and Congress passed a motion which gave him more authority over military decisions. By the end of 1965, President Johnson had sent 82,000 troops to Vietnam, and his officials wanted another 175,000. Due to the heavy demand for military personnel, the United States increased the number of men the draft provided each month.

In the 1960s anti-war movements started to occur in the U.S., mainly among those on college campuses and in more leftist circles, especially those who embraced the "hippie" lifestyle. College students were entitled to a deferment (2-S status) but were subject to the draft if they dropped out or graduated.[2][3] In 1967, the number of U.S. military personnel in Vietnam was around 500,000. The war was costing the U.S. $25 billion a year, and many of the young men drafted were being sent to a war they wanted no part of. Martin Luther King Jr. also started to support the anti-war movement, believing the war to be immoral and expressing alarm at the number of African-American soldiers that were being killed.[3]

15 November 1969 marked the largest anti-war protest in the history of the United States. It featured many anti-war political speakers and popular singers of the time. Many people at the time saw Richard Nixon as a liar; when he took office, he claimed that he would begin to withdraw American troops from Vietnam. After ten months of being in office, the president had yet to start withdrawals, and U.S. citizens felt lied to. Later, President Nixon claimed to have been watching sports as the anti-war demonstration took place outside the White House.[3]

After much debate within the Nixon administration and Congress, it was decided that a gradual transition to an all-volunteer force was affordable, feasible, and would enhance the nation's security. On 26 November 1969, Congress abolished a provision in the Military Selective Service Act of 1967 which prevented the president from modifying the selection procedure ("...the President in establishing the order of induction for registrants within the various age groups found qualified for induction shall not effect any change in the method of determining the relative order of induction for such registrants within such age groups as has been heretofore established..."),[4] and President Richard Nixon issued an executive order prescribing a process of random selection.[5]

Method

The 366 days of the year (including February 29) were printed on slips of paper. These pieces of paper were then each placed in opaque plastic capsules, which were then mixed in a shoebox and then dumped into a deep glass jar. Capsules were drawn from the jar one at a time and opened.

The first number drawn was 258 (14 September), so all registrants with that birthday were assigned lottery number 1. The second number drawn corresponded to 24 April, and so forth. All men of draft age (born 1 January 1944 to 31 December 1950) who shared a birth date would be called to serve at once. The first 195 birthdates drawn were later called to serve in the order they were drawn; the last of these was 24 September.[6]

Also on 1 December 1969, a second lottery, identical in process to the first, was held with the 26 letters of the alphabet. The first letter drawn was "J", which was assigned number 1. The second letter was "G", and so on, until all 26 letters were assigned numbers. Among men with the same birthdate, the order of induction was determined by the ranks of the first letters of their last, first, and middle names.[7] Anyone with initials "JJJ" would have been first within the shared birthdate, followed by "JGJ", "JDJ", and "JXJ"; anyone with initials "VVV" would have been last.[8]

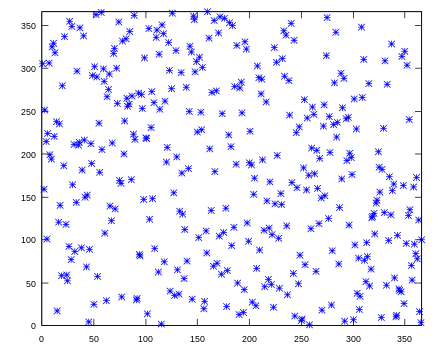

People soon noticed that the lottery numbers were not distributed uniformly over the months of the year. In particular, November and December births, or numbers 306 to 366, were assigned mainly to lower draft order numbers representing earlier calls to serve. This led to complaints that the lottery was not truly random as the legislation required. An analysis of the procedure suggested that mixing the 366 capsules in the shoe box did not randomize them sufficiently before placing them into the jar ("The capsules were put in a box month by month, January through December, and subsequent mixing efforts were insufficient to overcome this sequencing").[7] Only five days in December—2 December, 12 December, 15 December, 17 December and 19 December—were higher than the last call number of 195. Had the days been evenly distributed, 14 days in December would have been expected to remain uncalled. From January to December, the rank of the average draft pick numbers were 5, 4, 1, 3, 2, 6, 8, 9, 10, 7, 11, and 12. A Monte Carlo simulation found that the probability of a random order of months being this close to the 1–12 sequence expected for unsorted slips was 0.09%.[9]

Aftermath and modification

The draft lottery had social and economic consequences because it generated further resistance to military service. Those who resisted were generally young, well-educated, healthy men. The fear of service in Vietnam influenced many young men to join the National Guard. They were aware that the National Guard would be unlikely to send its soldiers to Vietnam. Many men were unable to join the National Guard even though they had passed their physicals, because many state National Guards had long waiting lists to enlist. Still others chose legal sanctions such as imprisonment, showing their disapproval by illegally burning their draft cards or draft letters, or simply not presenting themselves for military service. Others left the country, commonly moving to Canada.

The 1970s were a time of turmoil in the United States, beginning with the civil rights movement which set the standards for practices by the anti-war movement. The 1969 draft lottery only encouraged resentment of the Vietnam War and the draft. It strengthened the anti-war movement,[10] and all over the United States, people decried discrimination by the draft system "against low-education, low-income, underprivileged members of society".[11] The lottery procedure was improved the next year although public discontent continued to grow.[12]

For the draft lottery held on 1 July 1970 (which covered 1951 birthdates for use during 1971, and is sometimes called the 1971 draft), scientists at the National Bureau of Standards prepared 78 random permutations of the numbers 1 to 366 using random numbers selected from published tables.[13] From the 78 permutations, 25 were selected at random and transcribed to calendars using 1 = January 1, 2 = January 2, ... 365 = December 31. Those calendars were sealed in envelopes. 25 more permutations were selected and sealed in 25 more envelopes without transcription to calendars. The two sets of 25 envelopes were furnished to the Selective Service System.[13]

On 2 June, an official picked two envelopes, thus one calendar and one raw permutation. The 365 birthdates (for 1951) were written down, placed in capsules, and put in a drum in the order dictated by the selected calendar. Similarly, the numbers from 1 to 365 were written down and placed into capsules in the order dictated by the raw permutation.[13]

On 1 July, the drawing date, one drum was rotated for an hour and the other for a half-hour (its rotating mechanism failed).[13] Pairs of capsules were then drawn, one from each drum, one with a 1951 birthdate and one with a number 1 to 366. The first date and number drawn were 16 September and 139, so all men born 16 September 1951, were assigned draft number 139. The 11th draws were the date 9 July and the number 1, so men born July 9 were assigned draft number 1 and drafted first.[13]

Draft lotteries were conducted again from 1971 to 1975 (for 1952 to 1956 births). The draft numbers issued from 1972 to 1975 were not used to call any men into service as the last draft call was on 7 December, and authority to induct expired 1 July 1973.[8] They were used, however, to call some men born from 1953 to 1956 for armed forces physical examinations. The highest number called for a physical was 215 (for tables 1970 through 1976).[8] used to call some men born 1953 to 1956 for physical exams. The highest number called for a physical was 215 (for tables 1970 through 1976).[8] Between 1965 and 1972 the draft provided 2,215,000 service members to the U.S. military.[1]

Present day use

In the present, not much has changed on how the draft would be conducted if it was again ever needed. The Selective Service Committee who presides over the draft procedures has stored the large tumbler that holds all the number and dates that will be drawn to select candidates and the only thing that seems to have changed between the method of the past and the present one is that instead of using pieces of paper in blue capsules the SSC now uses ping-pong balls with the dates and numbers on them.[14]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Vietnam War - Vietnam War - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/1984/09/02/us/college-enrollment-linked-to-vietnam-war.html, https://timesmachine.nytimes.com/timesmachine/1967/03/19/107186611.pdf

- 1 2 3 "Vietnam War Protests - Vietnam War - HISTORY.com". HISTORY.com. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

- ↑ 91st U.S. Congress. "AN ACT To amend the Military Selective Service Act of 1967..." (pdf). United States Government Printing Office. (Pub.L. 91–124, 83 Stat. 220, enacted November 26, 1969)

- ↑ Peters, Gerhard; Woolley, John T. "Richard Nixon: "Executive Order 11497 - Amending the Selective Service Regulations to Prescribe Random Selection," November 26, 1969". The American Presidency Project. University of California - Santa Barbara.

- ↑ Selective Service System. "1970 Draft Lottery Results drawn December 1, 1969 sorted by date". Archived from the original on 15 September 2012. Retrieved 26 May 2012. See also sorted by numeric order.

- 1 2 Norton Starr (1997). "Nonrandom Risk: The 1970 Draft Lottery". Journal of Statistics Education 5.2 (1997). — The online edition includes instructions for getting the data online and a lesson plan for statistics class using the 1970 and 1971 draft lottery data.

- 1 2 3 4 "The Vietnam Lotteries". Selective Service System. June 18, 2009. Archived from the original on October 6, 2012.

- ↑ Henk Tijms. "Understanding Probability". Cambridge University Press. p. 101.

- ↑ Robert S. Erikson, Laura Stoker (February 2010). "Caught in the Draft: Vietnam Draft Lottery Status and Political Attitudes" (PDF). Columbia University.

- ↑ Fisher, Anthony C. (1969). "The Cost of the Draft and the Cost of Ending the Draft". American Economic Review. 59 (3). JSTOR 1808954.

- ↑ Ifill, Gwen (13 February 1992). "THE 1992 CAMPAIGN: New Hampshire; Clinton Thanked Colonel in '69 For 'Saving Me From the Draft'" – via NYTimes.com.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosenblatt, J. R.; Filliben, J. J. (1971). "Randomization and the Draft Lottery". Science. 171: 306–08. doi:10.1126/science.171.3968.306.

- ↑ "How the U.S. Draft Works". HowStuffWorks. 2001-10-18. Retrieved 2017-12-05.

External links

- Landscaper.net (2009). The Military Draft and 1969 Draft Lottery for the Vietnam War. Last modified 2009-03-24. Confirmed 2011-05-26. — contemporary news stories, images of Official Orders (call to physical exam, call to report), lottery results, Draft Board classifications, Vietnam troop levels, induction statistics 1917–73.

- David Lane (2003). Introduction to Graphs: Clearing Up the Draft with Graphs. Connexions. 18 July 2003. Confirmed 2011-05-26. — list of draft ranks, additional analysis.

- Selective Service System (2009). The Vietnam Lotteries. SSS: History and Records. Last updated 2015-09-19.

- Norton Starr (1997). "Nonrandom Risk: The 1970 Draft Lottery". Journal of Statistics Education 5.2 (1997). Confirmed 2011-05-26. — The online edition includes instructions for getting the data online and a lesson plan for statistics class using the 1970 and 1971 draft lottery data.

- Fienberg, S. E. (1971). "Randomization and Social Affairs: The 1970 Draft Lottery". Science. 171 (3968): 255–261. doi:10.1126/science.171.3968.255. PMID 17736218.

- Rosenbaum, David E. (4 January 1970). "Statisticians Charge Draft Lottery Was Not Random". New York Times. p. 66.