Djidjelli expedition

| Djidjelli expedition | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

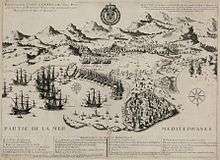

Antique engraving representing the French landing at Djidjelli (also transcribed "Gigeri") | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

Louis XIV François de Vendôme, Duc de Beaufort Charles-Félix de Galéan, Count of Gadagne | ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| Unknown |

Kingdom of France : 5650 men[1][2] 14 vessels[2] 8 galleys[2] Knights Hospitaller : 1 battalion[3] 7 galleys | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

500 dead 200 wounded |

2700 killed 30 cast-iron cannon 15 iron cannon 50 mortars | ||||||

The Djidjelli expedition[4] was a French military expedition in Algeria conducted between July and October 1664 by the Kingdom of France, with the assistance of the Order of St. John of Jerusalem in Malta, the United Provinces, and England, in the port city of Djidjelli (or Jijel) east of the Regency of Algiers. This "Africa campaign" was part of Louis XIV's vision for the Mediterranean. He wanted to protect the French merchant fleet from North African corsairs and also implement French global policy as a member of the League of the Rhine in the framework of the First Austro-Turkish War.

This military expedition aimed to seize the city of Djidjelli and fortify it, to establish a permanent naval base against the Berber corsairs of the regencies of Algiers and Tunis. The expedition was under the command of the Admiral of France, Francis of Vendome, Duke of Beaufort. The land forces were led by Lieutenant-General Charles-Félix de Galéan, Count of Gadagne.

Three months after the capture of the city, deprived of reinforcements due to an outbreak of the plague, and besieged by Berber, Kabyle and Ottoman troops, the forces of Louis XIV abandoned the city and reembarked for France. During the return crossing, an aging and poorly-repaired first-rate French ship La Lune, sank in the harbor of Toulon, resulting in more than 700 fatalities.

Reasons for the expedition

The young king Louis XIV -- whose reign began in 1661 after the death of Cardinal Jules Mazarin -- and his minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert wanted to safeguard trade conducted by the French merchant navy which, like those of other European nations, was continually attacked and pillaged by Barbary Coast pirates coming from the three regencies under Ottoman administration and protection in Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli.

The French expedition's goal was to "beat back the pirates mocking [France's] power", and ravaging the Mediterranean coasts.[5]

They chose to attack a city on the Barbary Coast halfway between Algiers and Tunis. The plan was to seize, fortify, and build a port there, using it as an advance post for future quick attacks against the corsairs, similar to what the English were doing at the time in Tangier (1661-1684). At the same period, on the western coast, the city of Oran had been in the hands of the Catholic Spanish monarchy since 1509.

They considered Bougie, Bône and Stora (near the former comptoir the Bastion de France), but eventually chose Djidjelli. This choice led to conflict between the commander of the expedition, his second in command, and the engineer in charge of fortifications.

Expedition

Duke of Beaufort takes Djidjelli (23 July)

The fleet mustered in Toulon on 2 July 1664 and made anchor at Bougie on 21 July after a halt in Menorca, in the port of Mahón. Here, the expedition was joined by Maltese galleys.

The expedition first opposed the Kabyles of the kingdom of Koukou and of Béni Abbès. Because they were dissenting against the Regency of Algiers, they refused its help at first.[6] However, because they failed in retaking the city in the end they accepted the passage of troops of the bey of Constantine and of the Regency of Algiers.[7]

On the morning of 23 July 1664, the galleys advanced to shore and intimidated the Kabyles with their artillery, thus allowing longboats (chaloupes) to ferry troops to shore near a landmark called le Marabout.[8] The choice of this landing place, which contained a shrine and a cemetery, incited heightened resistance from the inhabitants, which resulted in combat the following day.

The disembarking army consisted of about 4000 men, and the Maltese battalion 1200 men. The order was as follows: first the Picardy regiment commanded by M. de Vivonne disembarked, and then the Count of Gadagne at the head of the Maltese battalion, then the Duke of Beaufort and La Guillotiere.

The royal troops took Djidjelli the same day without much difficulty. The Count of Vivonne met with stiffer resistance at Le Marabout, but the Kabyles soon abandoned their positions to regain the mountains and the expeditionary force set up camp for the night.

Heavy fighting took place the next day. The Moors were seen waving a white flag, so the order was given to cease fire. The French seized this opportunity to parlay and establish friendly relations with the Arabs, but the Kabyles ambushed the expedition and ravaged it.[9] The intervention of the Maltese battalion with Charles-Félix de Galéan on a second front ended this lethal attack. The expedition lost 400 men and the Moors as many on their own side.

Strategic disagreement between Beaufort and Gadagne

A disagreement between the Duke of Beaufort and the Count of Gadagne is documented by the letter of September 12th 1664, addressed by Louis XIV to Monsieur de Gadagne. It seems that the Count of Gadagne already wanted, even before the expedition, to disembark at Bougie "then abandoned, better situated and more within reach of help than Djidjelli".[10]

After this attack the war council was divided in two clans: those who favored rapid fortification of the peninsula to allow it to sustain a siege (Gadagne, Vivonne, and the principal naval officers) and those thought other measures more important and above all wanted to await the orders of the king on the citadel project (Louis Nicolas de Clerville and the Duke of Beaufort).

Siege of Djidjelli (6 October)

An attack of Turks and Kabyles was repulsed by the besieged on 6 October 1664.

Arrival of reinforcement and departure of Beaufort (22 October)

To reinforce the initial expedition, on 20 September a convoy of six vessels and six barques laden with foodstuffs left for Africa.

Military reinforcements followed shortly afterwards: in turn leaving on 18 October from Toulon, Damien de Martel, the marquis de Martel, arrived as reinforcement, at the head of a squad (four vessels, one flûte and one brûlot) carrying two cavalry companies from the regiment of Conti, on 22 October 1664.[11] (See the correspondence between the king and the commanders of the expedition). The squad of M. de Martel was composed of the Dauphin (flagship), the Soleil (under M. de Kerjean), the ship La Lune (under François de Livenne de Verdille, the commander de Verdille), the Notre-Dame (under M. de la Giraudière), the Espérance (flûte, under M. Garnier) and of a prestigieux named the Triton (led by captain Champagne).

A message from the king, informed of the discord between the heads of the expedition, enjoined the Duke of Beaufort to retake ship and leave command of operations to de Gadagne. The cousin of Louis XIV and his fleet left Djidjelli for good on 22 October.

Retreat from Djidjelli (31 October)

With the outbreak of plague in Toulon, the embarcation of reinforcements and ammunition was cancelled.[12] So, besieged and judged too difficult to hold, the place was demolished and abandoned by the French, who re-embarked in the night of 30 October to 31 October 1664.[13]

Gadagne himself initially wanted combat. In the course of a war council on 30 October, after much hesitation from Gadagne to call it, the officers general and lower-ranking officers of the "army of Africa", that the re-embarkation was decided and drawn up as a letter to be sent to the king, signed by nineteen officers (principally not naval) of whom Louis Nicolas de Clerville, Raymond Louis de Crevant d'Humières, the marquis de Preuilly, Castellan and La Guillotière. Gadagne signed reluctantly, indicating he "did not believe he should or could hold a contrary opinion."[14] Even if the letter is presented as the opinion of all, many signatures are absent, including those of the most senior chiefs of the expedition, which is instructive as to an absence of unanimity.

The retreat was carried out using the vessels of Damien de Martel, marquis of Martel, arrived on 22 October, and without the help of the fleet of the Duke of Beaufort. Priority was given to troops who were beginning to be seen as unreliable, "the soldiers saying out loud that that they were going to become Turks".[15]

Wreck of La Lune

On its return to France, the entire fleet from the African campaign was sent into quarantine at île de Porquerolles by the Parlement de Provence (Parliament of Provence) because of the plague. La Lune, an old three-master that had arrived in Djidjelli as reinforcement on 22 October, was already in pitiful condition and poorly-repaired. It began taking on water as soon as it left harbor in Toulon. The vessel broke in two and sank near Toulon, before the Îles d'Hyères, with the ten first companies of the Picardy regiment aboard. More than 700 men drowned, among them General de la Guillotière, one of the two maréchaux de camp of the Count de Gadagne during the expedition.[16][14]

A hundred or so survivors managed to reach Port-Cros, but, abandoned on this desert island 7 km2, they all starved. The captain of the ship, who was a knight of Malta, the commander de Verdille and Antoine Boësset de La Villedieu (aide de camp of General de la Guillotière) escaped by swimming. There were only 24 survivors.[17]

In 1993, the wreck of La Lune was discovered in waters 90 m deep by IFREMER. The following year, Marie-Chantal Aiello produced a documentary for France 3, La Lune et le Roi Soleil (La Lune and the Sun King).[18]

Consequences

On 25 August 1665, the Duke of Beaufort destroyed two Algerian corsair ships and captured three others. On one of the latter he found the artillery that had been abandoned at Djidjelli in October 1664[19]..

A peace treaty was signed between the Duke of Beaufort and the Regency of Tunis on 25 November 1665. A second treaty was concluded with the Regency of Algiers on 17 May 1766. However, it was not until the bombardment of Algiers by Admiral Duquesne in 1682 for the comptoir français of the Bastion de France re-opened the following year.

Documentaries

- Marie-Chantal Aiello, La Lune et le Roi Soleil: Retour sur une tragédie navale, (La Lune and the Sun King: Return to a Naval Tragedy), 13 Production, France 3 Méditerranée / C.M.C.A / IFREMER, 1994

- L’épave de la Lune, (The Wreck of La Lune), La Marche des sciences, France Culture, broadcast 12/07/2012 1

Bibliography

- Antoine Augustin Bruzen de La Martinière and Yves Joseph La Motte, Histoire de la vie et du règne de Louis XIV, (History of the Life and Reign of Louis XIV), vol. 3, J. Van Duren, 1741

- Louis XIV, Œuvres de Louis XIV: Lettres particulières, (Works of Louis XIV: Personal Letters), Volume V, Paris, Treuttel et Würtz, 1806

- Ernest Mercier, Histoire de l'Afrique septentrionale (Berbérie) depuis les temps les plus reculés jusqu'à la conquête française (1830s) (History of North Africa (Barbary Coast) from Earliest Times to the French Conquest (1830s)), vol. 3, Ernest Leroux, Paris, 1891

- Guy Turbet-Delof, L'Affaire de Djidjelli (1664) dans la presse française du temps, (The Djidjelli Affair (1664) in the French Press of the Time), Taffard, 1968

- Bernard Bachelot, Louis XIV en Algérie: Gigeri 1664, (Louis XIV in Algeria: Higher 1664), Monaco, Éditions du Rocher, Art de la guerre collection, 2003 (reprint October 2011), 460 p. ( ISBN 978-2-268-04832-1, OCLC 53374515)

- Bernard Bachelot and Michel Albert, Raison d'état (Reasons of State), Paris, L'Harmattan, 2009, 171 p. ( ISBN 978-2-296-08423-0, OCLC 318870802)

- Bernard Bachelot, L’Expédition de Gigéri, 1664: Louis XIV en Algérie, (The Gigéri Expedition 1664: Louis XIV in Algeria) Les éditions Maison, Illustoria collection, 2014, 104 p. ( ISBN 2-917575-48-4)

- Michel Vergé-Franceschi (dir.), Jean Kessler (scientific advisor) et al., Dictionnaire d'Histoire maritime, (Dictionary of Naval History), éditions Robert Laffont, Bouquins collection, 2002 ( ISBN 9782221087510 and 9782221097441)

- Guy Le Moing, Les 600 plus grandes batailles navales de l'Histoire, (The 600 Greatest Naval Battles of History), Rennes, Marines Éditions, May 2011, 620 p. ( ISBN 235743077X and 9782357430778, OCLC 743277419)

- Bernard Bachelot, Louis XIV en Algérie: Gigeri 1664, (Louis XIV in Algeria: Giger 1664) Monaco, Rocher, 2003, 460 p. ( ISBN 2268048322)Document used to draft article

See also

References

- ↑ Revue de l'Orient, de l'Algërie et des colonies, (Review of the Orient, of Algeria and the Colonies), Volume 2 (1843); p. 204. [https://books.google.fr/books?id=M2MaAQAAIAAJ&pg=PA204 read online

- 1 2 3 Gérard Poumarède, La France et les Barbaresques (France and the Barbary Coast) in Étienne Taillemite, Denis Lieppe, Rivalités maritimes européennes: xvie – xixe siècles, (European Naval Rivalries: 16th - 19th Centuries), Revue d'histoire maritime no 4 PUPS, PUF, Presses Paris Sorbonne, 2005, p. 133

- ↑ Louis XIV 1806, p. 198, note

- ↑ also called "expédition de Gigéri ", "expédition de Gigery ", "expédition de Gigelly", "Gergily affair", "Djidjelli affair" or "campaign of Africa"

- ↑ Joëlle Chevé (2015). Marie-Thérèse d'Autriche: Epouse de Louis XIV [Marie-Thérèse of Austria: Wife of Louis XIV] (in French). Pygmalion. p. 568. ISBN 9782756417516.

- ↑ (Bachelot 2003, p. 304)

- ↑ (Bachelot 2003, p. 276)

- ↑ "marabout" translates as "hermit"

- ↑ Revue de l'Orient, de l'Algërie et des colonies, Volume 2 (1843); p. 205. url

- ↑ (Louis XIV 1806, p. 237-238, note)

- ↑ Olivier Lefèvre d'Ormesson, Journal d'Olivier Lefèvre d'Ormesson: et extraits des mémoires d'André Lefèvre d'Ormesson, (Journal of Olivier Lefèvre d'Ormesson: and Extracts from the Memoirs of André Lefèvre d'Ormesson), vol. 2, Imprimerie impériale, 1861, p.246

- ↑ Duc Paul de Noailles, Histoire de Madame de Maintenon et des principaux événements du règne de Louis XIV, (History of Madame de Maintenon and of the Primary Events of the Reign of Louis XIV), Volume 3, Comptoir des imprimeurs-unis, Lacroix-Comon, 1857, p.666

- ↑ Isaac de Larrey, Histoire de France sous le règne de Louis XIV, (History of France in the Reign of Louis XIV), vol. 1, Michel Bohm & Cie., Rotterdam 1734, p.464

- 1 2 Archives of the French Navy, vol. Campagnes, in Jal, Abraham du Quesne et la marine de son temps, (Abraham du Quesne and the Navy of his Time), 1873, p. 320

- ↑ Jal, 1873, p. 320

- ↑ Yves Durand; Jean-Pierre Bardet (2000). État et société en France aux XVII - VIIIe siecles [Society and the State in France During the 17th-18th Centuries I]. Presses Paris Sorbonne. p. 514.

- ↑ Bernard Bachelot (2009). Raison d'État. L'Harmattan. p. 30.

- ↑ http://www.film-documentaire.fr/4DACTION/w_fiche_film/461_1

- ↑ (Louis XIV 1806, p. 305, note)