Differential centrifugation

Differential centrifugation is a common procedure in microbiology and cytology used to separate certain organelles from whole cells for further analysis of specific parts of cells. In the process, a tissue sample is first lysed to break the cell membranes and mix up the cell contents. The lysate is then subjected to repeated centrifugations, where density separation causes a sediment to form known as "pellet". After each centrifugation the pellet is removed and the centrifugal force is increased. Finally, purification may be done through equilibrium sedimentation, and the desired layer is extracted for further analysis.

Theory

In general the equilibrium sedimentation profile is a function of particle-density alone; however, in a viscous fluid the rate of sedimentation is also a function of particle size. The reason for this is that (for a given radius of rotation and rotational velocity), the centrifugal force on a particle is proportional to the particle diameter cubed (for a given particle-density), whereas the force from viscous drag (or Stoke's force) is only proportional to the particle diameter squared. This means that larger particles sediment more quickly and at lower centrifugal forces, potentially causing a sedimentation profile that may be distorted by particle sizes and not quite in equilibrium with density. For this reason, multiple centrifugation steps are used in the separation process in order to obtain sedimentation profiles that are closer to having an equilibrium with density.

As an example, unbroken whole cells will pellet at low speeds and short intervals such as 1,000g for 5 minutes. Smaller cell fragments and organelles remain in the supernatant and require more force and longer durations to pellet. In general, one can enrich for the following cell components, in the separating order in actual application:

- Whole cells and nuclei;

- Mitochondria, chloroplasts, lysosomes, and peroxisomes;

- Microsomes (vesicles of disrupted endoplasmic reticulum); and

- Ribosomes and cytosol.

High g-force makes sedimentation of small particles much faster than Brownian diffusion, even for very small particles. When a centrifuge is used, Stokes' law must be modified to account for the variation in g-force with distance from the center of rotation.

where

- D is the minimum diameter of the particles expected to sediment (m)

- η (or µ) is the fluid dynamic viscosity (Pa.s)

- Rf is the final radius of rotation (m)

- Ri is the initial radius of rotation (m)

- ρp is particle volumetric mass density (kg/m³)

- ρf is the fluid volumetric mass density (kg/m³)

- ω is the angular velocity (radian/s)

- t is the time required to sediment from Ri to Rf (s)

Sample preparation

Before differential centrifugation can be carried out to separate different portions of a cell from one another, the tissue sample must first be lysed. In this process, a blender, usually a piece of porous porcelain of the same shape and dimension as the container, is used. The container is, in most cases, a glass boiling tube.

The tissue sample is first crushed and a buffer solution is added to it, forming a liquid suspension of crushed tissue sample. The buffer solution is a dense, inert, aqueous solution which is designed to suspend the sample in a liquid medium without damaging it through chemical reactions or osmosis. In most cases, the solution used is sucrose solution; in certain cases brine will be used. Then, the blender, connected to a high-speed rotor, is inserted into the container holding the sample, pressing the crushed sample against the wall of the container.

With the rotator turned on, the tissue sample is ground by the porcelain pores and the container wall into tiny fragments. This grinding process will break the cell membranes of the sample's cells, leaving individual organelles suspended in the solution. This process is called cell lysis. A portion of cells will remain intact after grinding and some organelles will be damaged, and these will be catered for in the later stages of centrifugation.

Ultracentrifugation

The lysed sample is now ready for centrifugation in an ultracentrifuge. An ultracentrifuge consists of a refrigerated, low-pressure chamber containing a rotor which is driven by an electrical motor capable of high speed rotation. Samples are placed in tubes within or attached to the rotor. Rotational speed may reach up to 100,000 rpm for floor model, 150,000 rpm for bench-top model (Beckman Optima Max-XP or Sorvall MTX150), creating centrifugal speed forces of 800,000g to 1,000,000g. This force causes sedimentation of macromolecules, and can even cause non-uniform distributions of small molecules.

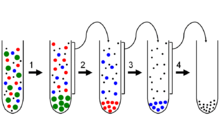

Since different fragments of a cell have different sizes and densities, each fragment will settle into a pellet with different minimum centrifugal forces. Thus, separation of the sample into different layers can be done by first centrifuging the original lysate under weak forces, removing the pellet, then exposing the subsequent supernatants to sequentially greater centrifugal fields. Each time a portion of different density is sedimented to the bottom of the container and extracted, and repeated application produces a rank of layers which includes different parts of the original sample. Additional steps can be taken to further refine each of the obtained pellets.

Sedimentation depends on mass, shape, and partial specific volume of a macromolecule, as well as solvent density, rotor size and rate of rotation. The sedimentation velocity can be monitored during the experiment to calculate molecular weight. Values of sedimentation coefficient (S) can be calculated. Large values of S (faster sedimentation rate) correspond to larger molecular weight. Dense particle sediments more rapidly. Elongated proteins have larger frictional coefficients, and sediment more slowly to ensure accuracy.

See also

| Library resources about Ultracentrifugation |

References

- Gerald Karp, Cell and molecular biology: Concepts and experiments, fourth edition, 2005, Von Hoffman press

- Roger A. Davis and Jean E. Vance, Structure, assembly and secretion of lipoproteins, 1996, Elsevier Science B. V.

http://www.chemeurope.com/en/encyclopedia/Sucrose_gradient_centrifugation.html