1943 Detroit race riot

| 1943 Detroit race riot | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | June 20–22, 1943 | ||

| Location | Detroit, Michigan | ||

| Methods | Rioting, arson, assault, street fighting | ||

| Parties to the civil conflict | |||

| |||

| Casualties | |||

| Death(s) | 34 | ||

| Injuries | 433 | ||

| Arrested | 1,800 | ||

The 1943 Detroit race riot took place in Detroit, Michigan, of the United States, from the evening of June 20 through the early morning of June 22. The race riot was ultimately suppressed by the use of 6,000 federal troops. It occurred in a period of dramatic population increase and social tensions associated with the military buildup of World War II, as Detroit's automotive industry was converted to the war effort. Existing social tensions and housing shortages were exacerbated by the arrival of nearly 400,000 migrants, both African-American and White Southerners, from the Southeastern United States between 1941 and 1943. The new migrants competed for space and jobs, as well as against white European immigrants and their descendants.

The Detroit riot was one of three that summer; it followed one in Beaumont, Texas, earlier that month, in which white shipyard workers attacked blacks after a rumor that a white woman had been raped; another riot preceded in Harlem, New York, where blacks attacked white-owned property in their neighborhood after rumors that a black soldier had been killed by a white policeman. In this wartime period, there were also racial riots in Los Angeles, California, and Mobile, Alabama.

The rioting in Detroit began among youths at Belle Isle Park on June 20, 1943; the unrest moved into the city proper and was exacerbated by false rumors of racial attacks in both the black and white communities. It continued until June 22. It was suppressed after 6,000 federal troops were ordered into the city to restore peace. A total of 34 people were killed, 25 of them black and most at the hands of white police or National Guardsmen; 433 were wounded, 75 percent of them black and property valued at $2 million ($27.5 million in 2015 US dollars) was destroyed; most of it happened in the black area of Paradise Valley, the poorest neighborhood of the city.[1]

At the time, white commissions attributed the cause of the riot to black hoodlums and youths. The NAACP identified deeper causes: a shortage of affordable housing, discrimination in employment, lack of minority representation in the police, and white police brutality. A late 20th-century analysis of the rioters showed that the white rioters were younger and often unemployed (characteristics that the riot commissions had falsely attributed to blacks, despite evidence in front of them). If working, the whites often held semi-skilled or skilled positions. They traveled long distances across the city to join the first stage of the riot near the bridge to Belle Isle Park and later traveled in armed groups explicitly to attack the black neighborhood. The black rioters were often older, established city residents, who in many cases had lived in the city for more than a decade. Many were married working men and were defending their homes and neighborhood against police and white rioters. They also looted and destroyed white-owned property in their neighborhood.[1]

Events leading up to the riot

By 1920, Detroit had become the fourth-largest city in the United States, with an industrial and population boom driven by the rapid expansion of the automobile industry.[2] In this era of continuing high immigration from southern and eastern Europe, the Ku Klux Klan in the 1920s established a substantial presence in Detroit during its early 20th-century revival.[3] The KKK became concentrated in midwestern cities rather than exclusively in the South.[2] It was primarily anti-Catholic and anti-Jewish in this period, but it also supported white supremacy.

The KKK contributed to Detroit's reputation for racial antagonism, and there were violent incidents dating from 1915.[1] Its lesser-known offshoot, Black Legion, was also active in the Detroit area. In 1936 and 1937, some 48 members were convicted of numerous murders and attempted murder, thus ending Black Legion's run. Both organizations stood for white supremacy. Detroit was unique among northern cities by the 1940s for its exceptionally high percentage of Southern-born residents, both black and white.[4]

Soon after the U.S. entry into World War II, the automotive industry was converted to military production; high wages were offered, attracting large numbers of workers and their families from outside of Michigan. The new workers found little available housing, and competition among ethnic groups was fierce for both jobs and housing. With Executive Order 8802, President Franklin D. Roosevelt on June 25, 1941, had prohibited racial discrimination in the national defense industry. Roosevelt called upon all groups to support the war effort. The Executive Order was applied irregularly, and blacks were often excluded from numerous industrial jobs, especially more skilled and supervisory positions.

Growing population

In 1941 at the beginning of the war, blacks numbered nearly 150,000 in Detroit, which had a total population of 1,623,452. Many of the blacks had migrated from the South in 1915 to 1930 during the Great Migration, as the auto industry opened up many new jobs. By summer 1943, after the United States had entered World War II, tensions between whites and blacks in Detroit were escalating; blacks resisted discrimination, as well as oppression and violence by the city's police department. The police force of the city was overwhelmingly white and the blacks resented this.

In the early 1940s, Detroit's population reached more than 2 million, absorbing more than 400,000 whites and some 50,000 black migrants, mostly from the American South, where racial segregation was enforced by law.[1] The more recent African Americans were part of the second wave of the black Great Migration, joining 150,000 blacks already in the city. The early residents had been restricted by informal segregation and their limited finances to the poor and overcrowded East Side of the city. A 60-block area east of Woodward Avenue was known as Paradise Valley, and it had aging and substandard housing.

White American migrants came largely from agricultural areas and especially rural Appalachia, carrying with them southern prejudices.[5] Rumors circulated among ethnic white groups to fear African Americans as competitors for housing and jobs. Blacks had continued to seek to escape the limited opportunities in the South, exacerbated by the Great Depression and second-class social status under Jim Crow. After arriving in Detroit, the new migrants found racial bigotry there, too. They had to compete for low-level jobs with numerous European immigrants, in addition to rural southern whites. Blacks were excluded from all of the limited public housing except the Brewster Housing Projects. They were exploited by landlords and forced to pay rents that were two to three times higher than families paid in the less densely populated white districts. Like other poor migrants, they were generally limited to the oldest, substandard housing.[6]

Housing challenges

Before the attack on Pearl Harbor, the administration of President Franklin D. Roosevelt had already been concerned about providing better housing for defense workers throughout the country, as much of the older housing in cities was substandard. On June 4, 1941, the Detroit Housing Commission approved two sites for defense worker housing projects - one for whites in northeast Detroit, an ethnic Polish area, and one for blacks. Originally the commission selected a site for the black residential project in a predominantly black area, but the U.S. government chose a site at Nevada and Fenelon streets, a predominantly Polish white neighborhood.[7]

Sojourner Truth Housing Project

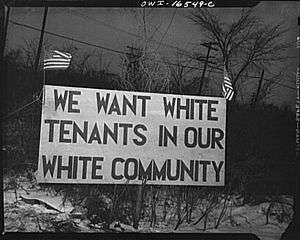

The Detroit housing development, primarily intended for blacks, was named Sojourner Truth, in honor of the prominent Civil War abolitionist and women's rights advocate. Local whites fiercely opposed allowing blacks to move in next to the ethnic Polish, all-white neighborhood. On January 20, 1942, the federal housing office responded to the Detroit Housing Commission's concerns, saying that the Sojourner Truth housing project would be used for whites and another would be selected for blacks. But when a suitable site for blacks could not be found, Washington D.C. housing authorities agreed to allow blacks into the housing project, beginning February 28, 1942.[7]

On February 27, 1942, some 150 local ethnic Polish whites vowed to keep out any black tenants in the new project; some were already scheduled to move in. In a nearby field, a cross was burning, alluding to the KKK symbol. By the following morning, the crowd of whites – many armed – had grown to 1,200. Blacks who had already signed leases and paid rent tried to pass through the whites' picket line, leading to a clash between white and black groups.[8] Despite the mounting opposition from white groups, six black families had moved into the project by the end of April.

To prevent violence, Detroit Mayor Edward Jeffries ordered the Detroit Police Department and state troops to keep the peace during this period. More than 1,100 city and state police officers and 1,600 Michigan National Guard troops (who were largely white) were mobilized and sent to the area around Nevada and Fenelon streets to guard the six African-American families who moved into the Sojourner Truth Homes. Eventually, 168 black families moved into the homes.[7] The police arrested 220 people, and 40 people were injured in the conflict; ill feelings were raised on both sides of the racial divide.[1]

Assembly line tensions

In June 1943, Packard Motor Car Company finally promoted three blacks to work next to whites in the assembly lines, in keeping with the anti-segregation policy required for the defense industry. In response, 25,000 whites walked off the job in a "hate" or wildcat strike at Packard, effectively slowing down the critical war production. Although whites had long worked with blacks in the same plant, many wanted control of certain jobs, and did not want to work right next to blacks. There was a physical confrontation at Edgewood Park. In this period, racial riots also broke out in Los Angeles, Mobile, Alabama and Beaumont, Texas, mostly over similar job issues at defense shipyard facilities.[1]

Riot

Altercations between youths started on June 20, 1943, on a warm Sunday evening on Belle Isle, an island in the Detroit River off Detroit's mainland. In what is considered a communal disorder,[9] youths fought intermittently through the afternoon. The brawl eventually grew into a confrontation between groups of whites and blacks on the long Belle Isle Bridge, crowded with more than 100,000 day trippers returning to the city from the park. From there the riot spread into the city. Sailors joined fights against blacks. The riot escalated in the city after a false rumor spread that a mob of whites had thrown an African-American mother and her baby into the Detroit River. Blacks looted and destroyed white property as retaliation.

Historian Marilynn S. Johnson argues that this rumor reflected black male fears about historical white violence against black women and children.[9][10] An equally false rumor that blacks had raped and murdered a white woman on the Belle Isle Bridge swept through white neighborhoods. Angry mobs of whites spilled onto Woodward Avenue near the Roxy Theater around 4 a.m., beating blacks as they were getting off street cars on their way to work.[8] They also went to the black neighborhood of Paradise Valley, one of the oldest and poorest neighborhoods in Detroit, attacking blacks who were trying to defend their homes. Blacks attacked white-owned businesses.

The clashes soon escalated to the point where mobs of whites and blacks were “assaulting one another, beating innocent motorists, pedestrians and streetcar passengers, burning cars, destroying storefronts and looting businesses."[5] Both sides were said to have encouraged others to join in the riots with false claims that one of "their own" had been attacked unjustly.[5] Blacks were outnumbered by a large margin, and suffered many more deaths, personal injuries and property damage. Out of the 34 people killed by police, 24 of them were African American.[11]

The riots lasted three days and ended only after Mayor Jeffries and Governor Harry Kelly asked President Franklin Roosevelt to intervene. He ordered in federal troops; a total of 6,000 troops imposed a curfew, restored peace and occupied the streets of Detroit. Over the course of three days of rioting, 34 people had been killed. 24 were African Americans; 17 were killed by the police (their forces were predominantly white and dominated by ethnic whites). Thirteen deaths remain unsolved. 9 deaths reported were white, and out of the 1,800 arrests made, 85% of them were African American, and only 15% were white.[5] Of the approximately 600 persons injured, more than 75 percent were black people.

Aftermath

After the riot, leaders on both sides had explanations for the violence, effectively blaming the other side. White city leaders, including the mayor, blamed young black hoodlums and persisted in framing the events as being caused by outsiders, people who were unemployed and marginal.[5] Mayor Jeffries said, "Negro hoodlums started it, but the conduct of the police department, by and large, was magnificent."[12] The Wayne County prosecutor believed that leaders of the NAACP were to blame as instigators of the riots.[5] Governor Kelly called together a Fact Finding Commission to investigate and report on the causes of the riot. Its mostly white members blamed black youths, "unattached, uprooted, and unskilled misfits within an otherwise law-abiding black community," and regarded the events as an unfortunate incident. They made these judgments without interviewing any of the rioters, basing their conclusions on police reports, which were limited.[1]

Other officials drew similar conclusions, despite discovering and citing facts that disproved their thesis. Dr. Lowell S. Selling of the Recorder's Court Psychiatric Clinic conducted interviews with 100 black offenders. He found them to be "employed, well-paid, longstanding (of at least 10 years) residents of the city", with some education and a history of being law abiding. He attributed their violence to their Southern heritage. This view was repeated in a separate study by Elmer R. Akers and Vernon Fox, sociologist and psychologist, respectively, at the State Prison of Southern Michigan. Although most of the black men they studied had jobs and had been in Detroit an average of more than 10 years, Akers and Fox characterized them as unskilled and unsettled; they stressed the men's Southern heritage as predisposing them to violence.[1] Additionally, a commission was established to determine the cause of the riot, despite the obvious and unequal amount of violence toward blacks. Later, it was found that the commission was extremely biased; it blamed the riot on blacks and their community leaders.[13]

Detroit's black leaders identified numerous other substantive causes, including persistent racial discrimination in jobs and housing, frequent police brutality against blacks and the lack of black representation on the force, and the daily animosity directed at their people by much of Detroit's white population.[5]

Following the violence, Japanese propaganda officials incorporated the event into its materials that encouraged black soldiers not to fight for the United States. They distributed a flyer titled "Fight Between Two Races".[14] The Axis Powers publicized the riot as a sign of Western decline.

Walter White, head of the NAACP, noted that there was no rioting at the Packard and Hudson plants, where leaders of the UAW and CIO had been incorporating blacks as part of the rank and file. These changes in the defense industry were directed by Executive Order by President Roosevelt and had begun to open opportunities for blacks.[15]

According to The Detroit News:

Future Supreme Court Justice, Thurgood Marshall, then with the NAACP, assailed the city's handling of the riot. He charged that police unfairly targeted blacks while turning their backs on white atrocities. He said 85 percent of those arrested were black while whites overturned and burned cars in front of the Roxy Theater with impunity as police watched. "This weak-kneed policy of the police commissioner coupled with the anti-Negro attitude of many members of the force helped to make a riot inevitable."[8]

Reinterpretation in 1990

A late 20th-century analysis of the facts collected on the arrested rioters has drawn markedly different conclusions. It notes that the whites who were arrested were younger, generally unemployed, and had traveled long distances from their homes to the black neighborhood to attack people there. Even in the early stage of the riots near Belle Isle Bridge, white youths traveled in groups to the riot area and carried weapons.[1]

Later in the second stage, whites continued to act in groups and were prepared for action, carrying weapons and traveling miles to attack the black ghetto along its western side at Woodward Avenue. Blacks who were arrested were older, often married and working men, who had lived in the city for 10 years or more. They fought closer to home, mainly acting independently to defend their homes, persons or neighborhood, and sometimes looting or destroying mostly white-owned property there in frustration. Where felonies occurred, whites were more often arrested for use of weapons, and blacks for looting or failing to observe the curfew imposed. Whites were more often arrested for misdemeanors. In broad terms, both sides acted to improve their positions; the whites fought out of fear, the blacks fought out of hope for better conditions.[1]

Representation in other media

Ross Macdonald, then writing under his real name, Kenneth Millar, used Detroit in the wake of this riot as one of the locales in his 1946 novel Trouble Follows Me.[16]

Comparison to 1967 riots

From the perspective of the early 21st century, the 1943 riot has been seen as a precursor of riots of the late 1960s in several cities.[17] The 1943 race riot was spurred by anti-black antipathy, as expressed by the proportion of whites who traveled to the primary black neighborhood to attack persons and property, by police brutality in the mostly white force, housing shortages due to racial discrimination, and fierce job competition in the late days of the Great Depression. The unequal numbers of blacks killed and wounded, blacks arrested, and property damage in the black neighborhood also expresses the social discrimination. Also expressive of this discrimination were the conclusions drawn by commissions, who ignored the evidence of the facts before them to repeat stereotypes about the rioters.

The 1967 Detroit Riot was different in that both blacks and whites participated in destruction in the city. Violence was directed at attacking police and the National Guard, and destroying property.

See also

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Dominic J. Capeci, Jr., and Martha Wilkerson, "The Detroit Rioters of 1943: A Reinterpretation", Michigan Historical Review, Jan 1990, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp. 49-72.

- 1 2 Kenneth Jackson, The Ku Klux Klan in the City, 1915-1930, Rowman & Littlefield, 1967, pp.127-129

- ↑ General Article: "Detroit Riots 1943", Eleanor Roosevelt, American Experience, PBS

- ↑ Gunnar Myrdal, An American Dilemma: The Negro Problem and American Democracy, New York: 1941, p. 568

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Sitkoff, "The Detroit Race Riot 1943"

- ↑ , Detroit News Archived May 26, 2012, at Archive.is

- 1 2 3 Sojourner Truth Housing Proj

- 1 2 3 "The 1943 Race Riots", Detroit News, February 10, 1999

- 1 2 Marilynn S. Johnson, "Gender, Race, and Rumours: Re-Examining the 1943 Race Riots," Gender and History (1998): 10:252-77.

- ↑ Patricia A. Turner, (1994). I Heard It Through the Grapevine: Rumor in African-American Culture, p. 51.

- ↑ White, Walter. "What Caused the Detroit Riot?". Archives. National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- ↑ Babson, Steve (May 1, 1986). Working Detroit: The Making of a Union Town. Wayne State University Press. p. 119.

- ↑ Woodford, Arthur (2012). "Detroit Riot of 1943". The Michigan Companion: A Guide to the Arts, Entertainment, Festivals, Food, Geography, Geology, Government, History, Holidays, Industry, Institutions, Media, People, Philanthropy, Religion, and Sports of the Great State of Michigan: 168–169 – via Gale Virtual Reference Library.

- ↑ A Fight Between Two Races

- ↑ Detroit Riots of 1943, Encyclopedia of African American History, 1896 to the Present: From the Age of Segregation to the Twenty-first Century, Five-volume Set, ed. Paul Finkelman, Oxford University Press, USA, 2009, pp. 59-60

- ↑ Trouble Follows Me, on https://goodreads.com/book/show/944440.Trouble_Follows_Me . Retrieved November 18, 2015.

- ↑ Kapell, Matthew Wilhelm (2009). "Miscreants, be they white or colored". Michigan Academician. 39: 213.

References

- Capeci, Dominic J., Jr., and Martha Wilkerson. "The Detroit Rioters of 1943: A Reinterpretation," Michigan Historical Review, Jan 1990, Vol. 16 Issue 1, pp 49–72

- Capeci, Dominic J., Jr., and Martha Wilkerson (1991). Layered Violence: The Detroit Rioters of 1943. Jackson, MS: University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 0-878-05515-0.

- Shogan, Robert, and Tom Craig (1964). The Detroit Race Riot: A Study in Violence. Philadelphia: Chilton Books.

- Sitkoff, Harvard. "The Detroit Race Riot 1943," Michigan History, May 1969, Vol. 53 Issue 3, pp 183–206, reprinted in John Hollitz, ed. Thinking Through The Past: Volume Two: since 1865 (Houghton Mifflin Company, 2005) ch 8.

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (1996). The Origins of the Urban Crisis. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-05888-1.

- "The 1943 Race Riots". The Detroit News. Archived from the original on January 21, 2013. Retrieved September 22, 2006.

- White, Walter. "What Caused the Detroit Riot?". National Association for the Advancement of Colored People Archives. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

External links

- Norman Prady. "The Story of How Mother Catered The Riots". The Detroit News.

- Vivian M. Baulch & Patricia Zacharias. "The 1943 Detroit race riots". The Detroit News.

- "Mayor Jeffries and Governor Kelly's June 21, 1943 radio speeches addressing the riots". LiveDetroit.tv.