Fallen angel

In Abrahamic religions, fallen angels are angels who were expelled from Heaven. The term "fallen angel" appears neither in the Bible nor in other Abrahamic scriptures, but is used of angels who were cast out of heaven or angels who sinned. Such angels are often malevolent towards humanity.

The idea of fallen angels derived from Jewish Enochic pseudepigraphy or the assumption that the "sons of God" (בני האלהים) mentioned in Genesis 6:1–4 are angels.[1] Some scholars consider it most likely that the Jewish tradition of fallen angels predates, even in written form, the composition of Gen 6:1–4.[2][3][lower-alpha 1] In the period immediately preceding the composition of the New Testament, some sects of Judaism, as well as many Christian Church Fathers, identified the "sons of God" (בני האלהים) of Genesis 6:1–4 as fallen angels.[5] The presence of these traditions in Christianity, not only in the East but also in the Latin-speaking West, is attested by the polemic of Augustine of Hippo (354–430) against the motif of giants born of the union between fallen angels and human women.[6] Rabbinic Judaism and Christian authorities after the third century rejected the Enochian writings and the notion of an illicit union between angels and women producing giants.[7][8][9] Christianity shifted the origin of the fallen angels towards the beginning of history. Accordingly, fallen angels became identified with angels who were led by Satan in rebellion against God[6] and became equated with demons.[10]

Islam also incorporates the concept of fallen angels.[11] However, like Rabbinic Judaism, some Islamic scholars reject the concept of fallen angels, emphasizing the piety of angels by citing certain verses of the Quran. Hasan of Basra not only emphasized verses which attest absolute obedience of angels to God, but also reinterpreted verses against this view. Accordingly, he read the term mala'ikah (angels) in reference to Harut and Marut in 2:102 as malikayn (kings), depicting them as ordinary men and not as angels.[12][13]

Mention of angels who physically descended (and figuratively "fell") to Mount Hermon is found in the Book of Enoch, which the Ethiopian Orthodox Church[14] and Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church accept as biblical canon; as well as in various pseudepigrapha.

Second Temple period

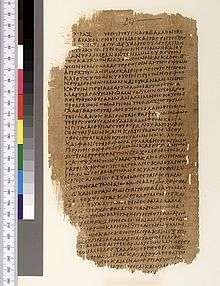

The concept of fallen angels is mostly found the Book of Enoch, verses 6–9; the Qumran Book of Giants; and perhaps in Genesis 6:1–4.[15] The reference to heavenly beings called "Watchers" originates in Daniel 4, in which there are three mentions, twice in the singular (v. 13, 23), once in the plural (v. 17), of "watchers, holy ones". The Ancient Greek word for watchers is ἐγρήγοροι (egrḗgoroi, plural of egrḗgoros), literally translated as "wakeful".[16] In the Book of Enoch these Watchers "fell" after they became "enamored" with human women. The Second Book of Enoch (Slavonic Enoch) refers to the same beings of the (First) Book of Enoch, but in the Greek transcription as Grigori.[17] A number of apocryphal works, including 1 Enoch (10.4),[18] link the fall of angels transgression with the Great Deluge.[19]

1 Enoch

According to 1 Enoch 7.2 the Watchers became "enamoured" with human women[18] and had intercourse with them. The offspring of these unions, and the knowledge they were given, corrupted human beings and the earth 1 Enoch 10.11–12.[18] Eminent among these angels are Shemyaza their leader and Azazel. Like many other fallen angels mentioned in 1 Enoch 8.1-9, Azazel introduced men to forbidden arts, but it is Azazel who is rebuked by Enoch himself for illicit instructions as stated in 1 Enoch 13.1.[20] According to 1 Enoch 10.6 God sent the archangel Raphael to chain Azazel in the desert Dudael as punishment. Further Azazel is blamed for the corruption of earth:

1 Enoch 10:12: "All the earth has been corrupted by the effects of the teaching of Azazyel. To him therefore ascribe the whole crime."

Treating theological issues such as the origin of evil as something supernatural, by shifting the sinfullness of mankind and their misdeeds to illicit angel instruction, is a unique motif found in the Book of Enoch and not found in later Jewish- and Christian theology.[21]

2 Enoch

The concept of fallen angels is also found in the Second Book of Enoch.

2 Enoch 29:3 "Here Satanail was hurled from the height together with his angels"—a probable Christian interpolation according to Charlesworth's Old Testament Pseudepigrapha

The text refers to "the Grigori, who with their prince Satanail rejected the Lord of light". The Grigori are identified with the Watchers of 1 Enoch.[22][23] The Grigori "went down on to earth from the Lord's throne", married women and "befouled the earth with their deeds", resulting in their confinement under the earth (2 Enoch 18:1–7) In the longer recension of 2 Enoch, chapter 29 refers to angels who were "thrown out from the height" when their leader tried to become equal in rank with the Lord's power (2 Enoch 29:1–4).

Most sources quote 2 Enoch as stating that those who descended to earth were three,[24] but Andrei A. Orlov, while quoting 2 Enoch as saying that three went down to the earth,[25] remarks in a footnote that some manuscripts put them at 200 or even 200 myriads.[22] In The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha: Apocalypic Literature and Testaments edited by James H. Charlesworth, manuscript J—taken as the best representative of the longer recension—has "and three of them descended" (p. 130); while manuscript A—taken as the best representative of the shorter recension—has "and they descended", which might indicate that all the Grigori descended, or 200 princes of them, or 200 princes and 200 followers, since it follows the phrase that "[t]hese are the Grigori, 200 princes of whom turned aside, 200 walking in their train" (p. 131).

Chapter 29, referring to the second day of creation (before the creation of human beings), says that "one from out the order of angels"[26] or, according to other versions of 2 Enoch, "one of the order of archangels"[27] or "one of the ranks of the archangels"[28] "conceived an impossible thought, to place his throne higher than the clouds above the earth, that he might become equal in rank to [the Lord's] power. And [the Lord] threw him out from the height with his angels, and he was flying in the air continuously above the bottomless." In this chapter, the name "Satanail" is mentioned only in a heading added in a single manuscript,[29][30] the GIM khlyudov manuscript,[31] which is a representative of the longer recension and was used in the English translation by R. H. Charles.

3 Enoch

3 Enoch mentions only three fallen angels called Azazel, Azza and Uzza. Similar to The first Book of Enoch, they taught sorcery on earth, causing corruption.[32] Unlike the first Book of Enoch, there is no mention of the reason for their fall and, according to 3 Enoch 4.6, they also later appear in heaven objecting to the presence of Enoch.

Jubilees

The Book of Jubilees refers to the Watchers, who are among the angels created on the first day.[33][34] However, unlike the (first) Book of Enoch, the Watchers are commanded by God to descent to earth and to instruct humanity.[35][36] It is only after they copulated with human women that they transgressed the laws of God.[37] These illicit unions resulted in demonic offspring, who battled each other until they died, while the Watchers were bound in the depths of the earth as punishment.[38] In Jubilees 10.1 another angel called Mastema refers to the Watchers.[37] He asks God to spare some of the demons, so he might use their aid to lead humankind into sin. Afterwards, he becomes their leader:

"'Lord, Creator, let some of them remain before me, and let them harken to my voice, and do all that I shall say unto them; for if some of them are not left to me, I shall not be able to execute the power of my will on the sons of men; for these are for corruption and leading astray before my judgment, for great is the wickedness of the sons of men.' (10:8)

Unlike in The (first) Book of Enoch, although the existence of supernatural evil is affirmed, evil is not introduced first by the fall of angels. Further, the fallen angels and demons seem to have no power independent from God but only act within his framework.[39]

Rabbinic Judaism

Although the concept of fallen angels developed from early Judaism during the Second Temple period, rabbis from the second century onwards turned against the Enochian writings, probably in order to prevent fellow Jew from worship and veneration of angels, but also to belittle the angels as a class and emphasize the omnipresence of God.[40] The rabbi Simeon b. Yohai cursed everyone who explained the Sons of God as angels. He states, Sons of God were actually sons of judges or sons of nobles. Evil was no longer attributed to heavenly forces, now it was dealt as an "evil inclination" (yetzer hara) within humans.[41] However, in some rabbinic writings, the "evil inclination" is attributed to Samael, who is in charge of several accuser angels,[42][43] but still subordinative to God.

Kabbalah

Although not fallen, evil angels, such as Samael, who also appeared in reference to the Enochian fallen angels, reappear in Kabbalah.[44] Accordingly, just as angels can be created by virtue, evil angels are formed by harboring evil thoughts or committing acts of wickedness.[45]

Christianity

_-_Walters_W10624R_-_Full_Page.jpg)

Bible

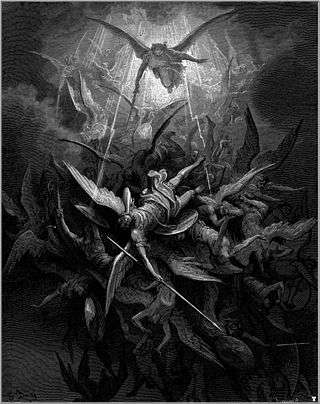

Origen and other Christian writers linked the fallen morning star of Isaiah 14:12 to Jesus' statement in Luke 10:18 that "I saw Satan fall like lightning from heaven" and to the mention of a fall of Satan in Revelation 12:8–9.[46] In Latin-speaking Christianity, the Latin word "lucifer" as employed in the late 4th-century AD Vulgate to translate הילל, gave rise to the name "Lucifer" for the person believed to be referred to in the text. The Book of Revelation tells of "that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world", being thrown down to the Earth together with his angels.[47] It further speaks of Satan as a great red dragon whose "tail swept a third part of the stars of heaven and cast them to the earth". In verses 7–9, Satan is defeated in the War in Heaven against Michael and his angels: "the great dragon was thrown down, that ancient serpent, who is called the devil and Satan, the deceiver of the whole world—he was thrown down to the earth, and his angels were thrown down with him".[48] Satan is often seen as the leader of the fallen angels.[49] Both 2 Peter 2:4 and Jude 1:6 refer to angels who have sinned against God and await punishment on Judgement Day.

Christian tradition has applied to Satan not only the image of the morning star in Isaiah 14:12, but also the denouncing in Ezekiel 28:11–19 of the king of Tyre, who is spoken of as having been a "cherub". Rabbinic literature saw these two passages as in some ways parallel, even if it perhaps did not associate them with Satan, and the episode of the fall of Satan appears not only in writings of the early Church Fathers and in apocryphal and pseudepigraphic works, but also in rabbinic sources.[50] However, "no modern evangelical commentary on Isaiah or Ezekiel sees Isaiah 14 or Ezekiel 28 as providing information about the fall of Satan".[51]

Early Christianity

During the period immediately before the rise of Christianity, the intercourse between the Watchers and human women was often seen as the first fall of the angels.[52]

Christianity stuck to the Enochian writings at least until the third century.[8] Many Church Fathers such as Irenaeus, Justin Martyr, Clement of Alexandria and Lactantius[53][54] accepted the application of the angelic descent myth to the "sons of God" passage in Genesis 6:1–4.[53] However some ascetics, such as Origen,[55] rejected this belief. According to the Church Fathers who accepted this doctrine, these angels were guilty of having transgressed the limits of their nature and of desiring to leave their heavenly abode to experience sensual experiences.[56] Irenaeus referred to fallen angels as apostates, who will be punished by an everlasting fire. Justin Martyr writes:

The wicked angels who will share in Satan's fate are the angels who sinned with the women before the Flood, who, far from being locked away to do further mischief, are on other than the troublesome Principalities and Powers of the Deutero-Pauline apistles and-believe it or not- are also the Gods of the Pagans.

Accordingly, pagan deities were regarded as fallen angels or their demonic offspring in disguise. Justin also held them responsible for Christian persecution during the first centuries.[57] Tertullian and Origen referred to fallen angels also as teachers of Astrology.[58]

The Fall of Lucifer probably finds its earliest identification with a fallen angel in Origen,[59][60] based on an interpretation of Isaiah 14:1–17, which describes a king of Babylon as the fallen "morning star" (in Hebrew, הילל). This description was interpreted typologically as an angel in addition to its literal application to a human king: the image of the fallen morning star or angel was thereby applied to Satan both in Jewish pseudepigrapha[44] and by early Christian writers,[61][62] following the equation of Lucifer to Satan in the pre-Christian century.[63]

Catholicism

By the third century, Christians began to reject the Enochian literature. The sons of God became identified merely with righteous men, more precisely with descendants of Seth who had been seduced by women descended from Cain. The cause of evil was shifted from superior powers to humans themselves, and to the very beginning of history; the expulsion of Satan and his angels on the one hand and the original sin of humans on the other hand.[8] However the Book of Watchers prevailed among Syriac Christians.[14] Augustine of Hippos work Civitas Dei became the major opinion of Western demonology and for the Catholic Church.[64] He rejected the Enochian writings and stated the sole origin of fallen angels was the rebellion of Satan.[6][65] As a result, fallen angels became equated with demons and depicted as asexual entities.[66] Whether or not fallen angels have a body became another topic of dispute during the Middle Ages.[64] Augustine of Hippo himself based his descriptions of demons on the perception of the Greek Daimon.[64] The Daimon was thought to be composed of etherial matter, a notion also assimilated to the fallen angels by Augustine.[67] However, these angels received their etherial body only after their fall.[67] Later scholars tried to explain the details of their nature, asserting that the etherial body is a mixture of fire and air, but that they are still composed of material elements. Others denied any physical relation to material elements, depicting the fallen angels as purely spiritual entities.[68] But even for those who believed the fallen angels had etherial bodies did not believe that they could produce any offspring.[69][70]

Augustine, in his Civitas Dei, divided the world into two Civitates: Two societies distinct from each other and opposed to each other like light and darkness.[71] The earthly city was caused by the act of rebellion of the fallen angels and is inhabited by wicked men and demons (fallen angels) led by Satan. On the other hand, the heavenly city is inhabited by righteuous men and the angels led by God.[71] Despite the appearance of dualism, Augustine always emphazised the souverignity of God. Accordingly, the inhabitants of the earthly city can only operate within their God-given framework.[65] The rebellion of angels was also a result of the God-given freedom of choice. The obedient angels are endowed with grace, giving them a deeper understanding of God's nature and the order of the cosmos. Illuminated by God-given grace, they became incapable to feel any desire to sin. The other angels, however, were not blessed with grace, thus they remained capable to sin. After these angels decided to sin, they fell from heaven and became demons.[72] In Augustine's view on angels, they can not become guily of carnal desires since they lack flesh, but of sins that are rooted in spirit and intellect such as pride and envy.[73] However, after they made their decision, they could not turn back.[74][75] The Catechism of the Catholic Church speaks of "the fall of the angels" not in spatial terms but as a radical and irrevocable rejection of God and his reign by some angels who, though created as good beings, freely chose evil, their sin being unforgivable because of the irrevocable character of their choice, not because of any defect in infinite divine mercy.[76] Catholicism rejects Apocatastasis, the reconcilement with God suggested by the Church Father Origen.[77]

Orthodox Christianity

Eastern Orthodox Christianity

Like Catholicism, Eastern Orthodox Christianity shares the basic belief in fallen angels as spiritual beings who rebelled against God. Unlike Catholicism, there is no established doctrine about the exact nature of fallen angels, but Eastern Orthodox Christianity unanimously agrees that the power of fallen angels is always inferior to God. Therefore, belief in fallen angels can always be assimilated with local lore, as long it does not break basic principles.[78] Some theologicans even suggest that fallen angels could be rehabilitated in the world to come.[79] Fallen angels, just like angels, play a significant role in the spiritual life of believers. As in Catholicism, fallen angels tempt and incite people into sin, but mental illness is also linked to fallen angels.[80] Those who have reached an advanced degree of spirituality are even thought to be able to envision them.[80] Rituals and sacraments performed by Eastern Orthodoxy are thought to weaken such demonic influences.[81]

Ethiopian Church

Unlike most other Churches, the Ethiopian Church accepts 1 Enoch and the Book of Jubilees as canonical.[82] As a result, the Church believes that sin did not originate in Adam's transgression alone, but also from Satan and other fallen angels. Together with demons, they continue to cause sin and corruption on earth.[83]

Protestantism

Like Catholisicm, Protestantism continues the concept of fallen angels as merely spiritual entities,[66] however it rejects angelology established by Catholicism. Martin Luthers sermons of the angels recount the exploits of the fallen angels rather than dealing with an angelic hierarchy.[84] Satan and his fallen angels are responsible for several misfortune in the world, but Luther always emphasized that the power of the good angels exceeds those of the fallen ones.[85] The Italian Protestant theologican Girolamo Zanchi offered further explanations for the reason behind the fall of the angels. According to Zanchi, the angels rebelled when the incarnation of Christ was revealed to them in incomplete form.[66] Nevertheless, Protestants are much less concerned with the cause of angelic fall, since it is thought as neither useful nor necessary to know.[66]

Universalism

In 19th-century Universalism, Universalists such as Thomas Allin (1891)[86] claimed that Clement of Alexandria, Origen, and Gregory of Nyssa taught that even the Devil and fallen angels will eventually be saved.[87]

Islam

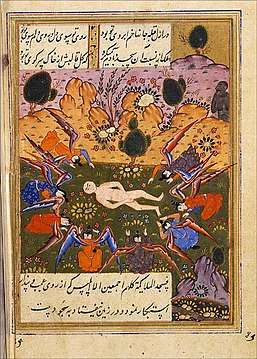

The concept of fallen angels is well known in Islam. The Quran mentions the fall of Iblis in several Surahs. Further Surah 2:112 implies that a pair of fallen angels introduced magic to humanity. However, the latter angels did not accompany Iblis. Fallen angels work in entirely different ways in the Quran and Tafsir.[88] According to Umm al-Kitab, Azazel boasted himself to be superior to God until he was thrown into lower celestrial spheres and finally ended up on earth.[11] Nahj al-Balagha, an Islamic collection of sermons, letters, and narrations attributed to Ali, admonishes humans to avoid haughtiness by stating: "Allah, the Glorified One, will not let a human being enter paradise if he does the same thing for which Allah turned an angel from it".[89] According to a hadith mentioned in Al-Tha'alibis Qisas Al-Anbiya, Iblis commands his host of rebel angels[90] and the fiercest jinn, from the lowest layer of hell. In a Shia narrative from Ja'far al-Sadiq, Idris (Enoch) met an angel, which the wrath of God fell upon, and his wings and hair were cut off; after Idris prayed for him to God, his wings and hair were restored. In return they become friends and at his request the angel took Idris to the Heavens to meet the angel of death.[91] Some recent non-Islamic scholars suggested Uzair, who is according to 9:30 called a son of God by Jews, originally referred to a fallen angel.[92] While exegetes almost unanimously identified Uzair as Ezra, there is no historical evidence that the Jews called him son of God. Thus, the Quran may refer not to the earthly Ezra, but to the heavenly Ezra, identifying him with the heavenly Enoch, who in turn became identified with the angel Metatron (also called lesser YHWH) in merkabah mysticism.[93]

Iblis

The Quran repeatedly tells about the fall of Iblis. According to Surah 2:30 the angels objected to God's intention to create a human, because they will cause corruption and shed blood,[94] echoing the account of 1 Enoch and the Book of Jubilees after the angels observed men causing unrighteousness.[95] However, after God demonstrated the superiority of Adam's knowledge in comparation to the angels, He orders them to prostrate themselves. After the command, only Iblis refused to follow the instruction. When God asked for the reason behind Iblis' refusal he boasted himself superior to Adam, because he was made of fire, thereupon God expelled him from heaven. In the early Meccan period, Iblis appears as a degraded angel.[96] But since he is called a jinni in 18:50, some scholars argue that Iblis was actually not an angel, but an entity apart, stating his numbering among the angels was just a reward for his previous righteousness. Therefore, they rejected the concept of fallen angels and emphasized the nobility of angels by quoting certain Quranic verses like 66:6 and 16:49, dinstinghuishing between infallible angels and jinn capable of sin. However the denotion jinni can not clearly exclude Iblis from being an angel.[97] According to Ibn Abbas, angels who guarded the Jinan (here: heavens) were called Jinni, just as humans who were from Mecca are called Mecci.[98][99] Other scholars asserted that a jinni is everything hidden from human eye, both angels and demons as well as earthly jinn. Therefore, this verse could not exclude Iblis from being an angel. In Surah 15:36 God grants Iblis' request to prove the unworthiness of humans. Surah 38:82 also confirms that Iblis' intrigues to lead humans astray are permitted by God's power.[100] However, as mentioned in Surah 17:65 Iblis' attempts to mislead God's servants are destined to fail.[100] The Quranic episode of Iblis parallels another wicked angel in the earlier Books of Jubilees: Like Iblis, Mastema requests God's permission to tempt humanity, and both are limited in their power, that is, not able to deceive God's servants.[101] However Iblis' disobedience derived not from the Watcher Stories, but can be traced back to the Cave of Treasuress, a work that probably holds the standard explanation in Proto-orthodox Christianity for the angelic fall of Satan.[94] Accordingly, Satan refuses to prostrate himself before Adam, because he is "fire and spirit" and thereupon he banished from heaven.[102][94] Unlike the majority opinion in later Christianity, the idea that Iblis tried to usurp the throne of God is alien to Islam and due to its strict monotheism unthinkable.[103]

Harut and Marut

Harut and Marut are a pair of angels mentioned in 2:102. Although the reason behind their stay on earth is not mentioned in the Quran,[104] a narration became canonizied in Islamic tradition. The Quranexegete Tabari attributed this story to Ibn Masud and Ibn Abbas.[105] Briefly summarized, the angels complained about the mischievousness of mankind and made a request to destroy them. Consequently, God offered a test to determine whether or not the angels would do better than humans for long: the angels will be endowed with humanlike urges and Satan would have power over them. The angels choose two (or in some accounts three) among themselves. However, on Earth, these angels entertained and acted upon sexual desires and were guilty of idol worship, whereupon they even killed an innocent witness. For their deeds, they were not allowed to ascend to Heaven again.[106] Probably the names Harut and Marut are of Zoroastrian origin and derived from two Amesha Spentas called Haurvatat and Ameretat.[107] Although the Quran gave these fallen angels Iranian names, mufassirs recognized them as from the Book of Watchers. In accordance with 3 Enoch, al-Kalbi named three angels, who descended to earth and even gave them their Enochian names. He explained that one of them returned to heaven and the other two changed their names to Harut and Marut.[108] However, like in the story of Iblis, the story of Harut and Marut does not contain any trace of angelic revolt. Rather the stories about fallen angels are related to a rivary between humans and angels.[109] As the Quran affirms, Harut and Marut are sent by God and, unlike the Watchers, they only instruct humans to witchcraft by God's permission,[110] just as Iblis can just tempt humans by God's permission.[111]

Footnotes

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 2

- ↑ Lester L. Grabbe, A History of the Jews and Judaism in the Second Temple Period (Continuum 2004 ISBN 9780567043528), p. 344

- ↑ Matthew Black, The Book of Enoch or I Enoch: A New English Edition with Commentary and Textual Notes (Brill 1985 ISBN 9789004071001), p. 14

- ↑ Grabbe 2004, p. 101

- ↑ Gregory A. Boyd, God at War: The Bible & Spiritual Conflict (InterVarsity Press 1997 ISBN 9780830818853), p. 138

- 1 2 3 Heinz Schreckenberg, Kurt Schubert, Jewish Historiography and Iconography in Early and Medieval Christianity (Van Gorcum, 1992, ISBN 9789023226536), p. 253

- ↑ Douglas 2011, p. 1384

- 1 2 3 Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 4

- ↑ Reed 2005, p. 218

- ↑ DALE BASIL MARTIN When Did Angels Become Demons? Journal of Biblical Literature 2010 p. 657

- 1 2 Christoph Auffarth, Loren T. Stuckenbruck The Fall of the Angels BRILL 2004 ISBN 978-9-004-12668-8 page 161

- ↑ Omar Hamdan Studien zur Kanonisierung des Korantextes: al-Ḥasan al-Baṣrīs Beiträge zur Geschichte des Korans Otto Harrassowitz Verlag 2006 ISBN 978-3-447-05349-5 page 292 (german)

- ↑ Al-Saïd Muhammad Badawi Arabic–English Dictionary of Qurʾanic Usage M. A. Abdel Haleem ISBN 978-9-004-14948-9, p. 864

- 1 2 Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 5

- ↑ Lester L. Grabbe, An Introduction to First Century Judaism: Jewish Religion and History in the Second Temple Period (Continuum International Publishing Group 1996 ISBN 9780567085061), p. 101

- ↑ ἐγρήγορος. Henry George Liddell. Robert Scott. A Greek–English Lexicon revised and augmented throughout by Sir Henry Stuart Jones with the assistance of Roderick McKenzie. Oxford. Clarendon Press. 1940. p. 474. Available online at the Perseus Project Texts Loaded under PhiloLogic (ARTFL project) at the University of Chicago.

- ↑ Andrei A. Orlov, Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (SUNY Press 2011 ISBN 978-1-43843951-8), p. 164

- 1 2 3 Laurence, Richard (1883). "The Book of Enoch the Prophet".

- ↑ Biblica (Vol. 58 ed.). St. Martin's Press. 1977. p. 586.

- ↑ Ra'anan S. Boustan, Annette Yoshiko Reed Heavenly Realms and Earthly Realities in Late Antique Religions Cambridge University Press 2004 ISBN 978-1-139-45398-1 p.60

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 p.6

- 1 2 Orlov 2011, p. 164

- ↑ Anderson 2000, p. 64: "In 2 Enoch 18:3... the fall of Satan and his angels is talked of in terms of the Watchers (Grigori) story, and connected with Genesis 6:1–4."

- ↑ Sources presenting one version of 2 Enoch and sources using a different version

- ↑ Andrei A. Orlov, Dark Mirrors SUNY Press 2011 ISBN 9781438439518, p.93

- ↑ "Most sources". Google.com. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- ↑ Marc Michael Epstein, Dreams of Subversion in Medieval Jewish Art and Literature Penn State University Press 1997

ISBN 9780271016054, p. 141

- and other sources

- ↑ James Hastings, A Dictionary of the Bible 1898 edition reproduced 2004 by the University Press of the Pacific ISBN 9781410217288, vol. 4, p. 409

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth, Old Testament Pseudepigrapha-set Hendrickson 2010 ISBN 9781598564891, p. 149

- ↑ Robert Charles Branden, Satanic Conflict and the Plot of Matthew Peter Lang 2006 ISBN 9780820479163, p. 30

- ↑ Charlesworth 2011, pp. 149, 92

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 p.256

- ↑ Jubilees 2.2

- ↑ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Book of Jubilees Society of Biblical Lit ISBN 9781589836433 p.57

- ↑ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Book of Jubilees Society of Biblical Lit ISBN 9781589836433 p.59

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 p. 90

- 1 2 Chad T. Pierce Spirits and the Proclamation of Christ: 1 Peter 3:18-22 in Light of Sin and Punishment Traditions in Early Jewish and Christian Literature Mohr Siebeck 2011 ISBN 9783161508585 p. 112

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 9780801494093 p.193

- ↑ Todd R. Hanneken The Subversion of the Apocalypses in the Book of Jubilees Society of Biblical Lit ISBN 9781589836433 p.60

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 5-6

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 6

- ↑ Geoffrey W. Dennis The Encyclopedia of Jewish Myth, Magic and Mysticism: Second Edition Llewellyn Worldwide 2016 ISBN 978-0-738-74814-6

- ↑ Yuri Stoyanov The Other God: Dualist Religions from Antiquity to the Cathar Heresy Yale University Press 2000 ISBN 978-0-300-19014-4

- 1 2 Adele Berlin; Maxine Grossman, eds. (2011). The Oxford Dictionary of the Jewish Religion. Oxford University Press. p. 651. ISBN 9780199730049. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ↑ https://www.myjewishlearning.com/article/angels/

- ↑ John N. Oswalt (1986). "The Book of Isaiah, Chapters 1–39". The International Commentary on the Old Testament. Eerdmans. p. 320. ISBN 978-0802825292. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ↑ Revelation 12:9

- ↑ Revelation 12:9

- ↑ Packer, J.I. (2001). "Satan: Fallen angels have a leader". Concise theology : a guide to historic Christian beliefs. Carol Stream, Ill.: Tyndale House. ISBN 0842339604.

- ↑ Hector M. Patmore, Adam, Satan, and the King of Tyre (BRILL 2012), ISBN 978-9-00420722-6, pp. 76–78

- ↑ Paul Peterson, Ross Cole (editors), Hermeneutics, Intertextuality and the Contemporary Meaning of Scripture (Avondale Academic Press 2013 ISBN 978-1-92181799-1), p. 246

- ↑ Gregory A. Boyd, God at War: The Bible & Spiritual Conflict, InterVarsity Press 1997 ISBN 9780830818853, p.138

- 1 2 Reed 2005, pp. 14, 15

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 page 149

- ↑ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 30

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 p.163

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the History of Judaism and Christianity: The Reception of Enochic Literature Cambridge University Press 2005 ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1 p.162

- ↑ Tim Hegedus Early Christianity and Ancient Astrology Peter Lang 2007 ISBN 978-0-820-47257-7 page 127

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 9780801494130 p. 130

- ↑ Philip C. Almond The Devil: A New Biography I.B.Tauris 2014 ISBN 9780857734884 p.42

- ↑ Charlesworth 2010, p. 149

- ↑ Schwartz 2004, p. 108

- ↑ "Lucifer". Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2014-03-11.

- 1 2 3 David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 39

- 1 2 David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 42

- 1 2 3 4 Joad Raymond Milton's Angels: The Early-Modern Imagination OUP Oxford 2010 ISBN 9780199560509 p. 77

- 1 2 David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 40

- ↑ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 49

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 9780801494130 p. 210

- ↑ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 45

- 1 2 Christoph Horn Augustinus, De civitate dei Oldenbourg Verlag 2010 ISBN 9783050050409 p. 158

- ↑ Jeffrey Burton Russell Satan: The Early Christian Tradition Cornell University Press 1987 ISBN 9780801494130 p. 211

- ↑ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 47

- ↑ Joad Raymond Milton's Angels: The Early-Modern Imagination OUP Oxford 2010 ISBN 9780199560509 p. 72

- ↑ David L Bradnick Evil, Spirits, and Possession: An Emergentist Theology of the Demonic BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-35061-8 page 43

- ↑ "Catechism of the Catholic Church, "The Fall of the Angels" (391-395)". Vatican.va. Archived from the original on 2012-09-04. Retrieved 2012-07-03.

- ↑ Frank K. Flinn Encyclopedia of Catholicism Infobase Publishing 2007 ISBN 978-0-816-07565-2 page 226

- ↑ Charles Stewart Demons and the Devil: Moral Imagination in Modern Greek Culture Princeton University Press 2016 ISBN 9781400884391 p.141

- ↑ Ernst Benz The Eastern Orthodox Church: Its Thought and Life Routledge 2017 ISBN 9781351304740 p.

- 1 2 Sergiĭ Bulgakov The Orthodox Church St Vladimir's Seminary Press 1988 ISBN 9780881410518 p. 128

- ↑ Charles Stewart Demons and the Devil: Moral Imagination in Modern Greek Culture Princeton University Press 2016 ISBN 9781400884391 p.147

- ↑ Loren T. Stuckenbruck, Gabriele Boccaccini Enoch and the Synoptic Gospels: Reminiscences, Allusions, Intertextuality SBL Press 2016 ISBN 9780884141181 p. 133

- ↑ James H. Charlesworth The Old Testament Pseudepigrapha Hendrickson Publishers 2010 ISBN 9781598564914 p. 10

- ↑ Peter Marshall, Alexandra Walsham Angels in the Early Modern World Cambridge University Press 2006 ISBN 9780521843324 p. 74

- ↑ Peter Marshall, Alexandra Walsham Angels in the Early Modern World Cambridge University Press 2006 ISBN 9780521843324 p. 76

- ↑ Allin, Thomas (1891). Christ Triumphant or Universalism Asserted as the Hope of the Gospel on the Authority of Reason, the Fathers, and Holy Scripture.

- ↑ Itter on Clement, Crouzel & Norris on Origen, etc.

- ↑ Amira El-Zein The Evolution of the Concept of the Jinn 1995 p. 232

- ↑ https://www.al-islam.org/nahjul-balagha-part-1-sermons/sermon-192-praise-be-allah-who-wears-apparel-honour-and-dignity

- ↑ Robert Lebling Legends of the Fire Spirits: Jinn and Genies from Arabia to Zanzibar I.B.Tauris 2010 ISBN 978-0-857-73063-3

- ↑ Muham Sakura Dragon The Great Tale of Prophet Enoch (Idris) In Islam Sakura Dragon SPC ISBN 978-1-519-95237-0

- ↑ Steven M. Wasserstrom Between Muslim and Jew: The Problem of Symbiosis under Early Islam Princeton University Press 2014 ISBN ISBN 9781400864133 p. 183

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 16

- 1 2 3 Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 page 66

- ↑ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 page 70

- ↑ Jacques Waardenburg Islam: Historical, Social, and Political Perspectives Walter de Gruyter, 2008 ISBN 978-3-110-20094-2 p. 38

- ↑ Mustafa ÖZTÜRK The Tragic Story of Iblis (Satan) in the Qur’an JOURNAL OF ISLAMIC RESEARCH p. 136

- ↑ Al-Tabari J. Cooper W.F. Madelung and A. Jones The commentary on the Quran by Abu Jafar Muhammad B. Jarir al-Tabari being an abbridged translation of Jamil' al-bayan 'an ta'wil ay al-Qur'an Oxford University Press Hakim Investment Holdings p.239

- ↑ Mahmoud M. Ayoub Qur'an and Its Interpreters, The, Volume 1, Band 1 SUNY Press ISBN 9780791495469 p.75

- 1 2 Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 page 71

- ↑ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 page 72

- ↑ Paul van Geest, Marcel Poorthuis, Els Rose Sanctifying Texts, Transforming Rituals: Encounters in Liturgical Studies BRILL 2017 ISBN 978-9-004-34708-3 p.83

- ↑ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 45

- ↑ مصباح المنير في تهذيب تفسير إبن كثير Ismāʻīl ibn ʻUmar Ibn Kathīr, Shaykh Safiur Rahman Al Mubarakpuri, Ṣafī al-Raḥmān Mubārakfūrī / The Meaning And Explanation Of The Glorious Qur'an: 1-203 Muhammad Saed Abdul-Rahman "The Story of Harut and Marut, and the Explanation That They Were Angels [[God said]]

- ↑ Amira El-Zein Islam, Arabs, and the Intelligent World of the Jinn Syracuse University Press 2009 ISBN 9780815650706 page 40

- ↑ Hussein Abdul-Raof Theological Approaches to Qur'anic Exegesis: A Practical Comparative-Contrastive Analysis Routledge 2012 ISBN 978-1-136-45991-7 page 155

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 10

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 10-11

- ↑ Patricia Crone THE BOOK OF WATCHERS IN THE QURÅN page 11

- ↑ Annette Yoshiko Reed Fallen Angels and the Afterlives of Enochic Traditions in Early Islam University of Pennsylvania 2015 p. 6

- ↑ Alberdina Houtman, Tamar Kadari, Marcel Poorthuis, Vered Tohar Religious Stories in Transformation: Conflict, Revision and Reception BRILL 2016 ISBN 978-9-004-33481-6 page 78

Notes

References

- Anderson, ed. by Gary (2000). Literature on Adam and Eve. Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004116001.

- Bamberger, Bernard J. (2006). Fallen angels : soldiers of satan's realm (first paperback ed.). Philadelphia, Pa.: Jewish Publ. Soc. of America. ISBN 0827607970.

- Charlesworth, edited by James H. (2010). The Old Testament pseudepigrapha. Peabody, Mass.: Hendrickson. ISBN 1598564919.

- Davidson, Gustav (1994). A dictionary of angels: including the fallen angels (1st Free Press pbk. ed.). New York: Free Press. p. 111. ISBN 978-0-02-907052-9.

- DDD, Karel van der Toorn, Bob Becking, Pieter W. van der Horst, (1998). Dictionary of deities and demons in the Bible (DDD) (2., extensively rev. ed.). Leiden: Brill. ISBN 9004111190.

- Douglas, James D. with Merrill Chapin Tenney, Moisés Silva (editors) (2011). Zondervan Illustrated Bible Dictionary. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN 9780310229834.

- Orlov, Andrei A. (2011). Dark mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in early Jewish demonology. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 1438439512.

- Platt, Rutherford H. (2004). Forgotten Books of Eden (Reprint ed.). Forgotten Books. p. 239. ISBN 1605060976.

- Reed, Annette Yoshiko (2005). Fallen angels and the history of Judaism and Christianity : the reception of Enochic literature (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge [u.a.]: Cambridge University Press. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-521-85378-1.

- Schwartz, Howard (2004). Tree of souls: The mythology of Judaism. New York: Oxford U Pr. ISBN 0195086791.

- Wright, Archie T. (2004). The origin of evil spirits the reception of Genesis 6.1-4 in early Jewish literature. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. ISBN 3161486560.

Further reading

- Ashley, Leonard R.N. The complete book of devils and demons. New York: Skyhorse Pub. ISBN 1616083336.

- Martin, Dale (2010). "When Did Angels Become Demons?". Journal of Biblical Literature. Society of Biblical Literature. 129 (4): 657–677. JSTOR 25765960.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Fallen angels. |

- Catholic Encyclopedia: Angels, see section "The Evil Angels"

- JewishEncyclopedia: Fall of Angels