Degenerative disc disease

| Degenerative disc disease | |

|---|---|

| Synonyms | degenerative disc disorder |

| |

| Degenerated disc, C5-C6 with osteophytes | |

| Classification and external resources | |

| Specialty | Orthopedics |

| ICD-10 | M51.3 |

| DiseasesDB | 6861 |

Degenerative disc disease (DDD) describes the natural breakdown of an intervertebral disc of the spine. Despite its name, DDD is not considered a disease, nor is it progressively degenerative. On the contrary, disc degeneration is often the effect of natural daily stresses and minor injuries that cause spinal discs to gradually lose water as the anulus fibrosus, or the rigid outer shell of a disc, weakens. As discs weaken and lose water, they begin to collapse. This can result in pressure being put on the nerves in the spinal column, causing pain and weakness.

While not always symptomatic, DDD can cause acute or chronic low back or neck pain as well as nerve pain depending on the location of the affected disc and the amount of pressure it places on the surrounding nerve roots.

The typical radiographic findings in DDD are black discs, disc space narrowing, vacuum disc, end plate sclerosis, and osteophyte formation.[1][2]

DDD can greatly affect quality of life. Disc degeneration is a disease of micro/macro trauma and of aging, and though for most people is not a problem, in certain individuals a degenerated disc can cause severe chronic pain if left untreated.

Cause

The term, degenerative disc disease is a slight misnomer because it is not technically a disease, nor is it strictly degenerative. It is not considered a disease because degenerative changes in the spine are natural and common in the general population.[3]

There is a disc between each of the vertebrae in the spine. A healthy, well-hydrated disc will contain a great deal of water in its center, known as the nucleus pulposus, which provides cushioning and flexibility for the spine. Much of the mechanical stress that is caused by everyday movements is transferred to the discs within the spine and the water content within them allows them to effectively absorb the shock. At birth, a typical human nucleus pulposus will contain about 80% water.[4] However natural daily stresses and minor injuries can cause these discs to gradually lose water as the anulus fibrosus, or the rigid outer shell of a disc, weakens.[5]

This water loss makes the discs less flexible and results in the gradual collapse and narrowing of the gap in the spinal column. As the space between vertebrae gets smaller, extra pressure can be placed on the discs causing tiny cracks or tears to appear in the anulus. If enough pressure is exerted, it's possible for the nucleus pulposus material to seep out through the tears in the anulus and can cause what is known as a herniated disc.

As the two vertebrae above and below the affected disc begin to collapse upon each other, the facet joints at the back of the spine are forced to shift which can affect their function.[6]

Additionally, the body can react to the closing gap between vertebrae by creating bone spurs around the disc space in an attempt to stop excess motion.[7] This can cause issues if the bone spurs start to grow into the spinal canal and put pressure on the spinal cord and surrounding nerve roots as it can cause pain and affect nerve function.[8] This condition is called spinal stenosis.

For women, there is good evidence that menopause and related estrogen-loss are associated with lumbar disc degeneration, usually occurring during the first 15 years of the climacteric. The potential role of sex hormones in the etiology of degenerative skeletal disorders is being discussed for both genders.[9]

Degenerative disc disease can also occur in other mammals besides humans. It is a common problem in several dog variants and attempts to remove this disease from dog populations have led to several crosses, such as the Chiweenie.[10]

Signs and symptoms

Degenerative disc disease can result in lower back or upper neck pain, but this isn't always true across the board. In fact, the amount of degeneration does not correlate well with the amount of pain patients experience.[8] Many people experience no pain while others, with exactly the same amount of damage have severe, chronic pain.[11] Whether a patient experiences pain or not largely depends on the location of the affected disc and the amount of pressure that is being put on the spinal column and surrounding nerve roots.

Nevertheless, degenerative disc disease is one of the most common sources of back pain and affects approximately 30 million people every year.[3] With symptomatic degenerative disc disease, the pain can vary depending on the location of the affected disc. A degenerated disc in the lower back can result in lower back pain, sometimes radiating to the hips, as well as pain in the buttocks, thighs or legs. If pressure is being placed on the nerves by exposed nucleus pulposus, sporadic tingling or weakness through the knees and legs can also occur.

A degenerated disc in the upper neck will often result in pain to the neck, arm, shoulders and hands; tingling in the fingers may also be evident if nerve impingement is occurring.

Pain is most commonly felt or worsened by movements such as sitting, bending, lifting and twisting.

After an injury, some discs become painful because of inflammation and the pain comes and goes. Some people have nerve endings that penetrate more deeply into the anulus fibrosus (outer layer of the disc) than others, making discs more likely to generate pain. In the alternative, the healing of trauma to the outer anulus fibrosus may result in the innervation of the scar tissue and pain impulses from the disc, as these nerves become inflamed by nucleus pulposus material. Degenerative disc disease can lead to a chronic debilitating condition and can have a serious negative impact on a person's quality of life. When pain from degenerative disc disease is severe, traditional nonoperative treatment may be ineffective.

Mechanisms

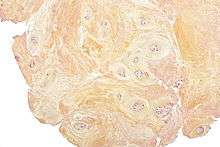

Degenerative discs typically show degenerative fibrocartilage and clusters of chondrocytes, suggestive of repair. Inflammation may or may not be present. Histologic examination of disc fragments resected for presumed DDD is routine to exclude malignancy.

Fibrocartilage replaces the gelatinous mucoid material of the nucleus pulposus as the disc changes with age. There may be splits in the anulus fibrosus, permitting herniation of elements of nucleus pulposus. There may also be shrinkage of the nucleus pulposus that produces prolapse or folding of the anulus fibrosus with secondary osteophyte formation at the margins of the adjacent vertebral body. The pathologic findings in DDD include protrusion, spondylolysis, and/or subluxation of vertebrae (spondylolisthesis) and spinal stenosis. It has been hypothesized that Propionibacterium acnes may play a role.[12]

Diagnosis

Diagnosis of degenerative disc disease will usually consist of an analysis of a patient's individual medical history, a physical exam designed to reveal muscle weakness, tenderness or poor range of motion, and an MRI scan to confirm the diagnosis and rule out other causes.

Treatment

Often, degenerative disc disease can be successfully treated without surgery. One or a combination of treatments such as physical therapy, anti-inflammatory medications such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, traction, or epidural steroid injection often provide adequate relief of troubling symptoms.

Surgery may be recommended if the conservative treatment options do not provide relief within two to three months. If leg or back pain limits normal activity, if there is weakness or numbness in the legs, if it is difficult to walk or stand, or if medication or physical therapy are ineffective, surgery may be necessary, most often spinal fusion. There are many surgical options for the treatment of degenerative disc disease, including anterior[13] and posterior approaches. The most common surgical treatments include:[14]

- Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion: A procedure that reaches the cervical spine (neck) through a small incision in the front of the neck. The intervertebral disc is removed and replaced with a small plug of bone or other graft substitute, and in time, that will fuse the vertebrae.

- Cervical corpectomy: A procedure that removes a portion of the vertebra and adjacent intervertebral discs to allow for decompression of the cervical spinal cord and spinal nerves. A bone graft, and in some cases a metal plate and screws, is used to stabilize the spine.

- Dynamic Stabilisation: Following a discectomy, a stabilisation implant is implanted with a 'dynamic' component. This can be with the use of Pedicle screws (such as Dynesys or a flexible rod) or an interspinous spacer with bands (such as a Wallis ligament). These devices off load pressure from the disc by rerouting pressure through the posterior part of the spinal column. Like a fusion, these implants allow maintain mobility to the segment by allowing flexion and extension.

- Facetectomy: A procedure that removes a part of the facet to increase the space.

- Foraminotomy: A procedure that enlarges the vertebral foramen to increase the size of the nerve pathway. This surgery can be done alone or with a laminotomy.

- Intervertebral disc annuloplasty (IDET): A procedure wherein the disc is heated to 90 °C for 15 minutes in an effort to seal the disc and perhaps deaden nerves irritated by the degeneration.

- Intervertebral disc arthroplasty: also called Artificial Disc Replacement (ADR), or Total Disc Replacement (TDR), is a type of arthroplasty. It is a surgical procedure in which degenerated intervertebral discs in the spinal column are replaced with artificial ones in the lumbar (lower) or cervical (upper) spine.

- Laminoplasty: A procedure that reaches the cervical spine from the back of the neck. The spinal canal is then reconstructed to make more room for the spinal cord.

- Laminotomy: A procedure that removes only a small portion of the lamina to relieve pressure on the nerve roots.

- Microdiscectomy: A minimally invasive surgical procedure in which a portion of a herniated nucleus pulposus is removed by way of a surgical instrument or laser while using an operating microscope or loupe for magnification.

- Percutaneous disc decompression: A procedure that reduces or eliminates a small portion of the bulging disc through a needle inserted into the disc, minimally invasive.

- Spinal decompression: A non-invasive procedure that temporarily (a few hours) enlarges the intervertebral foramen (IVF) by aiding in the rehydration of the spinal discs.

- Spinal laminectomy: A procedure for treating spinal stenosis by relieving pressure on the spinal cord. A part of the lamina is removed or trimmed to widen the spinal canal and create more space for the spinal nerves.

Traditional approaches in treating patients with DDD-resultant herniated discs oftentimes include discectomy — which, in essence, is a spine-related surgical procedure involving the removal of damaged intervertebral discs (either whole removal, or partially-based). The former of these two discectomy techniques involved in open discectomy is known as Subtotal Discectomy (SD; or, aggressive discectomy) and the latter, Limited Discectomy (LD; or, conservative discectomy). However, with either technique, the probability of post-operative reherniation exists and at a considerably high maximum of 21%, prompting patients to potentially undergo recurrent disk surgery.[15]

New treatments are emerging that are still in the beginning clinical trial phases. Glucosamine injections may offer pain relief for some without precluding the use of more aggressive treatment options. In the US, artificial disc replacement is viewed cautiously as a possible alternative to fusion in carefully selected patients, yet it is widely used in a broader range of cases in Europe, where multi-level disc replacement of the cervical and lumbar spine is common. Adult stem cell therapies for disc regeneration are in their infancy, however initial clinical trials have shown cell transplantation to be safe and initial observations suggest some beneficial effects for associated pain and disability.[16] Investigation into mesenchymal stem cell therapy knife-less fusion of vertebrae in the United States began in 2006.[17]

Researchers and surgeons alike have conducted clinical and basic science studies to uncover the regenerative capacity possessed by the large animal species involved (humans and quadrupeds) for potential therapies to treat the disease.[18] Some therapies, carried out by research laboratories in New York, include introduction of biologically-engineered, injectable riboflavin cross-linked high density collagen (HDC-laden) gels into disease spinal segments to induce regeneration, ultimately restoring functionality and structure to the 2 main inner and outer components of vertebral discs — annulus fibrosis and the nucleus pulposus.[19]

See also

References

- ↑ Benzon, Honorio; Raja, Srinivasa N.; Fishman, Scott E.; Liu, Spencer; Cohen, Steven P. (30 June 2011). Essentials of Pain Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. ISBN 1-4377-3593-2 – via Google Books.

- ↑ Herring, William. Learning Radiology: Recognizing the Basics (3rd ed.). Saunders. ISBN 978-0323328074.

- 1 2 "Degenerative Disc Disease Treament|Degeneratice Disc Disease Treatments". www.instituteforchronicpain.org. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ Kasbia, V. (2005, Sep 08). Degenerative disc disease. Pembroke Observer Retrieved fromhttp://search.proquest.com/docview/354183403

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease". University of Maryland Medical Center. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- ↑ Lee, Yu Chao; Zotti, Mario Giuseppe Tedesco; Osti, Orso Lorenzo (2016). "Operative Management of Lumbar Degenerative Disc Disease". Asian Spine Journal. 10 (4): 801–19. doi:10.4184/asj.2016.10.4.801. PMC 4995268. PMID 27559465.

- ↑ "Bone spurs Causes – Mayo Clinic". Mayo Clinic. Retrieved 2017-01-04.

- 1 2 Lim Jae, Y. (December 2016). "Degenerative Disc Disease". Atlantic Brain & Spine. Retrieved 4 January 2017.

- ↑ Lou C et al. (Aug 2014) "Menopause is associated with lumbar disc degeneration: a review of 4230 intervertebral discs." Climacteric. 17 (6) :700-4. doi: 10.3109/13697137.2014.933409. Retrieved 01-21-2017.

- ↑ "Chiweenie - Dogs 101 | Animal Planet". www.animalplanet.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease | NorthShore". www.northshore.org. Retrieved 2017-01-05.

- ↑ Capoor, Manu N.; Ruzicka, Filip; Schmitz, Jonathan E.; James, Garth A.; Machackova, Tana; Jancalek, Radim; Smrcka, Martin; Lipina, Radim; Ahmed, Fahad S. (2017-04-03). "Propionibacterium acnes biofilm is present in intervertebral discs of patients undergoing microdiscectomy". PLOS ONE. 12 (4): e0174518. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0174518. ISSN 1932-6203. PMC 5378350. PMID 28369127.

- ↑ Sugawara, Taku (2015). "Anterior Cervical Spine Surgery for Degenerative Disease: A Review". Neurologia medico-chirurgica. 55 (7): 540–546. doi:10.2176/nmc.ra.2014-0403.

- ↑ "Degenerative Disc Disease – When Surgery Is Needed". Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Shin, Byung-Joon (2014). "Risk factors for recurrent lumbar disc herniations". Asian Spine Journal. 8 (2): 211–215. doi:10.4184/asj.2014.8.2.211. PMC 3996348. PMID 24761206.

- ↑ Sakai, D. & Schol, J. Cell therapy for intervertebral disc repair: Clinical perspective. J Orthop Translat 9, 8-18, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jot.2017.02.002 (2017).

- ↑ "Mesoblast files spinal fusion IND". Australian Life Scientist. 2006-11-27. Archived from the original on 2009-01-08. Retrieved 2009-02-16.

- ↑ Moriguchi, Yu; Alimi, Marjan; Khair, Thamina; Manolarakis, George; Berlin, Connor; Bonassar, Lawrence J.; Härtl, Roger (2016). "Biological Treatment Approaches for Degenerative Disk Disease: A Literature Review of In Vivo Animal and Clinical Data". Global Spine Journal. 6 (5): 497–518. doi:10.1055/s-0036-1571955. PMC 4947401. PMID 27433434.

- ↑ Pennicooke, Brenton; Hussain, Ibrahim; Berlin, Connor; Sloan, Stephen R.; Borde, Brandon; Moriguchi, Yu; Lang, Gernot; Navarro-Ramirez, Rodrigo; Cheetham, Jonathan (2018). "Annulus Fibrosus Repair Using High-Density Collagen Gel: An In Vivo Ovine Model". Spine. 43 (4): E208–E215. doi:10.1097/BRS.0000000000002334. ISSN 1528-1159. PMID 28719551.