Death of Irene Garza

| |

| Date | April 1960 |

|---|---|

| Location | McAllen, Texas |

| Cause | Suffocation |

| Arrest(s) | Former priest John Feit, 2016 |

| Convicted | Murder |

| Sentence | Life imprisonment |

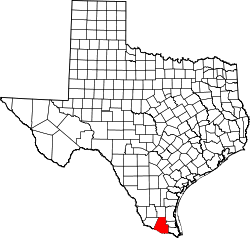

Irene Garza (November 15, 1934 – April 1960) was a South Texas teacher and beauty queen whose death was the subject of investigation for several decades. Garza was last seen alive on April 16, 1960, when she went to confession at a church in McAllen, Texas. She was reported missing the following morning. Following the largest volunteer search to that date in the Rio Grande Valley, Garza's body was discovered in a canal on April 21. An autopsy concluded that she had been sexually assaulted before being killed; the cause of death was suffocation.

Father John Feit, the priest who heard Garza's last confession, was the only identified suspect in her death. Two clergymen, Dale Tacheny and Joseph O'Brien, came forward in 2002 to say that Feit had confessed to them shortly after the murder, but the Hidalgo County district attorney considered the evidence too weak to secure a conviction. The district attorney brought the case before a grand jury in 2004, but Feit, Tacheny and O'Brien were not subpoenaed, and Feit was not indicted.

The investigation into Garza's death was renewed in 2015 after a new district attorney took office in Hidalgo County. In February 2016, the 83-year-old Feit was arrested in Arizona in connection with Garza's death. He was later extradited to Texas. His murder trial began in late November 2017. On December 7, 2017, Feit was found guilty of her death and on December 8, 2017, he was sentenced to life in prison.

Background

Garza was born in 1934.[1] Her parents, Nicolas and Josefina, owned a dry cleaning business in McAllen, a city in Hidalgo County and part of the South Texas border region known as the Rio Grande Valley. By the time Garza was a teenager, her parents' business had become successful and the family was able to move from the south side of McAllen to a more affluent area on the north side of the city. She was a graduate of McAllen High School. White students made up a majority at the school, and Garza was the first Latina to become a twirler or head drum majorette. She was crowned the 1958 Miss All South Texas Sweetheart and was a homecoming queen at Pan American College.[2]

At the time of her death, Garza was a second grade teacher; she taught indigent students at an elementary school on the south side of McAllen. In a letter that Garza wrote to a friend shortly before her disappearance, Garza described herself as extremely shy, but she expressed fulfillment in her work. Noting that she had recently become secretary of her parent-teacher association, she said that she was beginning to feel more confident in herself. A member of the Legion of Mary, Garza took her Catholic faith seriously. In her letter, she indicated that was finding comfort in attending Mass and Communion every day.[2]

Garza lived with her parents, and on Saturday, April 16, 1960, she told them that she was going to confession at Sacred Heart Church in McAllen. Garza was often conspicuous in the congregation because of her striking appearance, and several parishioners remembered seeing Garza at the church that night. When Garza's parents did not hear from her that evening, they first thought that she had stayed at the church for midnight mass. When Garza did not return home by 3:00 am, Nicolas and Josefina went to the McAllen Police Department to report their daughter missing.[1]

Investigation

On April 18, in a trail of evidence stretching several hundred yards down a McAllen road, passersby found Garza's purse, her left shoe and her lace veil. Authorities and volunteers started a search that was the largest in Rio Grande Valley history at that time. A woman called the Garza home claiming to be Irene, saying that she had been kidnapped and taken to a hotel in nearby Hidalgo, but the call was found to have been a prank. Another person told an Edinburg waitress that he had killed Garza, but that was found to be a joke made after the man had been drinking heavily.[2]

Garza's body was located in a canal on April 21, in an area several miles away from the other evidence. From the postmortem examination, medical examiners could tell that Garza had died of suffocation. She was raped while unconscious and beaten. There was bruising over both of her eyes and to the right side of her face. Any physical evidence that might have identified an attacker, such as hair, blood or semen, appeared to have been washed away during the time the body spent in the canal.[2]

Law enforcement officials questioned about 500 people across several Texas cities, including known sex offenders and Garza's family members, co-workers and ex-boyfriends.[2] They carried out almost 50 polygraph examinations, and they offered a $2,500 reward for information about her death, which was larger than any amount of money previously offered in a Rio Grande Valley murder case.[1] South Texas businessmen later posted $10,000 of reward money. The priest who heard Garza's last confession, Father John Feit, came under suspicion soon after her disappearance.[2] The 27-year-old priest had been at the church since completing seminary training in San Antonio.[3]

Church members reported that Father Feit's confession line moved slowly that night and that he was away from the sanctuary several times. When the canal at the crime scene was drained several days after the discovery of Garza's body, Feit's photo slide viewer was found in the canal. Fellow priests noticed scratch marks on Feit's hands after midnight mass, and they said it was irregular for Feit to have taken Garza to the church rectory to hear her confession.[2] The McAllen Police Department initially said that Feit passed polygraph tests, but the tests were later said to be inconclusive.[4]

Feit initially denied hearing Garza's confession in the rectory, but he later admitted to having done so. He accounted for his absence from the sanctuary by explaining that he had broken his glasses that night; he said that he often played with his glasses nervously as he listened to confession. Feit said that he had driven back to the pastoral house to get another pair of glasses, and when he arrived he had no key, so he had to climb into the house on the second floor. He said that he sustained the scratches on his hands as he was climbing the outside of the brick structure.[2]

Three weeks before Garza's death, a woman named Maria America Guerra had been sexually assaulted while kneeling at the communion rail at another Catholic church in the area.[5] Rumor held that Father Feit was responsible, but local church leaders discouraged people from considering the possibility that a priest could have been involved in a violent crime. Feit admitted to visiting a priest at that church on the day of Guerra's attack, but he denied assaulting her. He was later charged with rape, and the trial ended in a hung jury. In 1962, rather than facing a second trial, Feit entered a plea of no contest to a misdemeanor charge of aggravated assault, and he paid a $500 fine.[1] Years later, Feit said he did not understand that a no contest plea would result in his conviction.[6]

Stagnation in the case

After the legal proceedings in the Guerra case, Feit was sent to Assumption Abbey, a Trappist monastery in Missouri. An abbot there told monk Dale Tacheny that Feit had killed someone and he asked Tacheny to counsel Feit for a few months and to determine whether Feit had the disposition to become a monk. Tacheny says that Feit confessed to hurting a young lady and murdering another one, but that it was not Tacheny's job to judge Feit at the time, so Feit's confession went unreported to authorities for many years.[7]

Feit did not feel comfortable with the monastic lifestyle at Assumption Abbey.[7] He was sent to Jemez Springs, New Mexico, to a treatment retreat for troubled priests run by the Servants of the Paraclete. Feit joined the order as a staff member and worked his way into a supervisory role at the center. Father James Porter came to the center after he was known to have begun molesting children in the 1960s, and Feit cleared him for placement in another parish. Porter was later defrocked and imprisoned after abusing as many as 100 children.[8][9] Feit left the priesthood in the 1970s. He got married, moved to the Phoenix area, and had three children. He worked at the Society of Saint Vincent de Paul as a food charity volunteer for 17 years.[7]

In 2002, thinking that the Garza murder had taken place in San Antonio because Feit had trained there, Tacheny called authorities in that city and said that he could no longer keep the secret of Feit's confession. The investigation into Garza's death was reopened that year. Texas Rangers investigator Rudy Jaramillo contacted Father Joseph O'Brien, a priest who worked with Feit at the time of the Garza murder. O'Brien told a television program in 2000 that he did not know anything about Garza's death. He softened with Jaramillo, first telling the investigator that he had suspected Feit at the time, then admitting that Feit had confessed shortly after the murder.[10] In August 2002, the polygraph examiner who tested Feit in 1960 said that he questioned the reported results. Feit had been said to have passed his polygraph and documentation was later amended to show that the results were inconclusive, but the examiner felt that Feit had failed the test.[4]

Rene Guerra served as district attorney in Hidalgo County from the 1980s until 2014.[1] Guerra elected not to bring the case before a grand jury until 2004.[11] Tacheny, O'Brien and Feit did not receive subpoenas in the case, and the grand jury declined to indict Feit. O'Brien died in 2005.[11] Guerra was reluctant to revisit the case, saying that the early police investigation had been shoddy, that O'Brien was suffering from dementia when he was questioned, and that there was no physical evidence. He said that Jaramillo had inappropriately fed Tacheny the location of the murder after the monk mistakenly said it occurred in San Antonio.[10] Guerra angered Garza's family by asking, "Why would anyone be haunted by her death? She died. Her killer got away."[2]

Renewed interest

In 2014, district court judge Ricardo Rodriguez campaigned to unseat Guerra as district attorney, and the Garza case arose as a campaign issue.[12] Rodriguez said that he wanted justice for the Garza family. He said that he would take a new look at Garza's case if he were elected.[13] Rodriguez won the election. In the days after the vote was announced, Guerra sought to appoint Rodriguez as a special prosecutor in the Garza case. Rodriguez declined, saying that he preferred to take a new look at the evidence once he took control of the district attorney's office in January 2015.[14] In April, he announced that the Garza case was open again. Without mentioning any suspects or elaborating on new evidence, he said that several employees in his office were working on the case.[13]

In February 2016, Feit was arrested in Scottsdale, Arizona.[15] He was 83 at the time of his arrest, and he used a walker when he appeared in court. Feit was extradited to Texas in March 2016 and incarcerated at the Hidalgo County Sheriff's Office (Texas) Adult Detention Facility.[16] He entered a plea of not guilty. The prosecution requested a $750,000 bond, while the defense team asked for a $100,000 bond, adding that Feit had stage 3 kidney and bladder cancer. Judge Luis Singleterry set a $1 million bond.[17]

Status hearings in the case were held in June and November 2016, and the discovery process was ongoing as of November.[18][19] In February 2017, a judge set a late April 2017 trial date, and Feit remained under medical supervision at the Hidalgo County Jail.[20] In April, Feit's defense filed for a change of venue because they believed that their client would not receive a fair and impartial trial in Hidalgo County. They filed a 700-page document with evidence showing that reporters allegedly condemned Feit as a murderer, and that the only reason why he avoided prosecution for years was because the Catholic Church protected him.[21] Sometime in March, Tacheny testified against Feit in closed deposition. This was permitted under Texas law given the witness' age and exclusive knowledge of the case.[22]

On May 24, Judge Singleterry heard arguments from the plaintiff and the defense on the request for the change of venue.[23] On June 7, he denied a request for a change of venue after considering that the defendant failed to prove that there was prejudice against him in the Hidalgo community.[24] On July 19, Feit appeared in court for a prehearing.[25] The trial was expected to place on September 11.[26] However, on September 10, the court decided to push the trial back because of scheduling conflicts; one of Feit's attorneys was defending another high-profile murder suspect in Hidalgo County. Feit appeared in court on September 11 – for the first time without prison uniform – expecting to face trial that week.[22] The initial phase of jury selection was done in mid-September; the trial was delayed until mid-October.[27] On October 30, Feit's defense filed a motion for continuance; jury selection was reset to November 14 and the November 6 trial date was moved back to November 28.[28]

On December 7, Feit was convicted of Garza's murder.[29] In the punishment phase of the trial, Feit's defense attorney asked that Feit be given probation, citing his lack of felony convictions since Garza's death. The prosecution asked for a sentence of 57 years, which was symbolic of the amount of time that had passed since Garza's death. On December 8, the jury pronounced a sentence of life in prison.[30]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hernandez, Kristian; Zazueta-Castro, Lorenzo (February 13, 2016). "Irene Garza's family feels weight has been lifted as former priest faces murder charge". The Monitor. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Colloff, Pamela (January 20, 2013). "Unholy act". Texas Monthly. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Fuentes, Diana (February 25, 2016). "Ex-priest coming back to Texas to stand trial in the gruesome death of a Valley beauty queen". San Antonio Express-News. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Perez-Treviño, Emma (August 11, 2002). "Priests polygraph disputed by examiner". The Brownsville Herald. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Wang, Yanan (February 11, 2016). "Break in cold case: Police arrest former beauty queen's priest in her 1960 killing". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Convicted priest says he was 'out of loop'". amarillo.com. Amarillo Globe-News. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Santos, Fernanda (February 11, 2016). "Ex-priest is arrested in 1960 killing of Texas beauty queen". The New York Times. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Ex-priest baffled by arrest in 1960 McAllen schoolteacher slaying | Texas | Dallas News". DallasNews.com. February 10, 2016. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Perez-Treviño, Emma (July 22, 2002). "40-year-old murder, unsolved, unforgotten Profile: Crime records paint portrait of murder victim". The Brownsville Herald.

- 1 2 Schlesinger, Richard (April 16, 2016). "48 Hours: The last confession". CBS News. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- 1 2 Tuchman, Gary; Bronstein, Scott. "Timeline: The killing of Irene Garza". CNN.com. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Fischler, Jacob (March 3, 2014). "On eve of election, Rene Guerra fights back on Irene Garza issue". The Monitor. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- 1 2 Custer, Ashly (April 15, 2015). "Irene Garza's cold case under review in Hidalgo County". KGBT-TV. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Custer, Ashly (March 11, 2014). "Ricardo Rodriguez responds to Rene Guerra's request to appoint him in Irene Garza case". KGBT-TV. Retrieved October 20, 2016.

- ↑ Jamieson, Alastair; Helsel, Phil (February 10, 2016). "Ex-priest, 83, arrested over beauty queen's 1960 murder". NBC News. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Ex-priest accused in woman's death extradited to TX". NBC 5 Dallas-Fort Worth. March 9, 2016. Retrieved March 5, 2017.

- ↑ Ortiz, Analise (March 14, 2016). "Former priest pleads not guilty in Irene Garza murder case, bond set at $1 million". KGBT-TV. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ Zazueta-Castro, Lorenzo (June 6, 2016). "Former priest appears in court again; plans in works for inspection of church grounds". The Monitor. Retrieved October 21, 2016.

- ↑ "No new motions filed in John Feit's pretrial hearing". KRGV-TV. November 3, 2016. Retrieved December 5, 2016.

- ↑ Zazueta-Castro, Lorenzo (February 13, 2017). "Tentative trial date set in Feit case". The Monitor. Retrieved March 4, 2017.

- ↑ Zazueta-Castro, Lorenzo (April 9, 2017). "Former priest's attorney files for change of venue". The Brownsville Herald.

- 1 2 De la Garza, Erik (September 12, 2017). "Cold-Case Murder Trial Meets Second Delay". Courthouse News Service.

- ↑ Lopez-Puente, Naxiely (May 24, 2014). "Judge mulls change of venue in Irene Garza case". The Monitor.

- ↑ Zazueta-Casto, Lorenzo (June 7, 2017). "Feit trial to remain in Hidalgo County". The Monitor.

- ↑ Martinez, Amy (July 18, 2017). "Former Priest to Appear Before Judge for Pre-Trial Hearing". RGV Proud. Nexstar Media Group.

- ↑ Nelson, Aaron (June 8, 2017). "Fall trial for priest accused in 1960 beauty queen murder will stay in Valley". San Antonio Express-News.

- ↑ Zazueta-Castro, Lorenzo (September 10, 2017). "Feit, Patterson cases intersect as trial proceedings loom". The Brownsville Herald.

- ↑ Smith, Molly (October 31, 2015). "Feit trial pushed back to late November". The Monitor. Retrieved November 13, 2017.

- ↑ "Former priest convicted of murdering Texas beauty queen in 1960". NY Daily News. Retrieved 2017-12-08.

- ↑ Smith, Molly (December 8, 2017). "Former priest John Feit gets life in prison for schoolteacher's murder". The Monitor. Retrieved December 9, 2017.

Further reading

- Fanning, Diane (2016). "3". Holy Homicide. Diane Fanning. p. 92.