Death Takes a Holiday

| Death Takes a Holiday | |

|---|---|

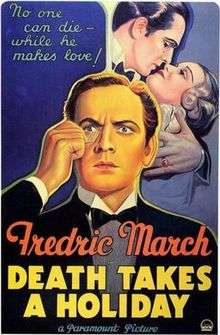

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Mitchell Leisen |

| Produced by |

E. Lloyd Sheldon Emanuel Cohen |

| Screenplay by |

Maxwell Anderson Gladys Lehman |

| Based on | Death Takes a Holiday (play) by Walter Ferris, adapted from La Morte in Vacanza by Alberto Casella |

| Starring |

Fredric March Evelyn Venable Guy Standing Katharine Alexander Gail Patrick Kent Taylor Helen Westley Henry Travers Kathleen Howard |

| Cinematography | Charles Lang |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures |

Release date | February 23, 1934[1] |

Running time | 79 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

Death Takes a Holiday is a 1934 American Pre-Code romantic drama starring Fredric March, Evelyn Venable and Guy Standing. It is based on the 1924 Italian play La Morte in Vacanza by Alberto Casella (1891-1957), as adapted in English for Broadway in 1929 by Walter Ferris.

Synopsis

After years of questioning why people fear him, Death takes on human form (Fredric March) for three days so that he can mingle among mortals and find an answer. He finds a host in Duke Lambert (Guy Standing) after revealing himself and his intentions to the Duke, and takes up temporary residence in the Duke's villa. However, events soon spiral out of control as Death falls in love with the beautiful young Grazia (Evelyn Venable). As he does so, Duke Lambert, the father of Grazia's mortal lover Corrado (Kent Taylor), begs him to give Grazia up and leave her among the living. Death must decide whether to seek his own happiness, or sacrifice it so that Grazia may live.

Cast

- Fredric March - Prince Sirki/Death

- Evelyn Venable - Grazia

- Guy Standing - Duke Lambert

- Katherine Alexander - Alda

- Gail Patrick - Rhoda

- Kent Taylor - Corrado

- Helen Westley - Stephanie

- Henry Travers - Baron Cesarea

- Kathleen Howard - Princess Maria

Releases

The theatrical premiere of the film was on February 23, 1934 at the Paramount Theatre in New York City.[1] The home video releases have been:

- Death Takes a Holiday (VHS). Universal Studios. March 8, 1999.

- Death Takes a Holiday (DVD). Universal Studios. January 9, 2007. (as part of the Meet Joe Black Ultimate Edition)

- Death Takes a Holiday (DVD). Universal Studios. January 11, 2010.

Reception

The film was an enormous critical success.[2] Time called it "thoughtful and delicately morbid", while Mordaunt Hall for The New York Times wrote that "it is an impressive picture, each scene of which calls for close attention".

Richard Watts, Jr, for the New York Herald Tribune, described it as "An interesting, frequently striking and occasionally beautiful dramatic fantasy", while the Chicago Daily Tribune said that March was "completely submerged in probably the greatest role he has ever played."[3] Variety called it "the kind of story and picture that beckons the thinker, and for this reason is likely to have greater appeal among the intelligensia." It praised March's performance as "skillful".[4] John Mosher of The New Yorker wrote that the film was "nicely done", although he suggested it was "a little obnoxious with all its talk of being in love with death."[5]

The film was a box office disappointment for Paramount.[6]

The American Film Institute recognized the film with a nomination in its 2002 list, AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions.[7]

Remakes and adaptations

It aired as the drama of the week on Cecil B. DeMille's Lux Radio Theatre on March 22, 1937, starring Fredric March as Death and his wife, actress Florence Eldridge, as Grazia. Universal Studios, which acquired the rights to the film in 1962 following a merger with then-owners MCA, made a 1971 television production featuring Yvette Mimieux, Monte Markham, Myrna Loy, Melvyn Douglas and Bert Convy. Loy related in her biography that the production was marred by a decline in filming production standards; she described a frustrated Douglas storming off the set and returning to his home in New York when a tour guide interrupted the filming of one of his dramatic scenes to point out Rock Hudson's dressing room. The film was remade by Universal again in 1998 as Meet Joe Black starring Brad Pitt, Claire Forlani and Anthony Hopkins.

It was adapted into a musical by Maury Yeston with the book by Peter Stone and Thomas Meehan. It began previews Off-Broadway on June 10, and officially opened on July 21, 2011, in a limited engagement through September 4, 2011, at the Laura Pels Theatre at the Harold & Miriam Steinberg Center for Theatre in a production by Roundabout Theatre Company.[8] A May 2006 episode of the television drama Medium also builds on the concept of death portrayed as a man. The season 2 episode is similarly called, "Death Takes a Policy."

Further reading

- Loy, Myrna and Kotsilibis-Davies, James — Being and Becoming, Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. 1987; ISBN 1-55611-101-0

- Quirk, Lawrence J. — The Films of Fredric March, The Citadel Press, 1971; ISBN 0-8065-0413-7

References

- 1 2 "Death Takes a Holiday (1934)". Toronto Film Society. October 21, 2014. Retrieved June 22, 2015.

- ↑ Churchill, Douglas W. The Year in Hollywood: 1934 May Be Remembered as the Beginning of the Sweetness-and-Light Era (gate locked); New York Times [New York, NY], December 30, 1934: X5; retrieved December 16, 2013.

- ↑ Striner, Richard (2011). Supernatural Romance in Film: Tales of Love, Death and the Afterlife. McFarland and Company. pp. 21–22. ISBN 9780786484874.

- ↑ "Death Takes a Holiday". Variety. New York: Variety, Inc. February 27, 1934.

- ↑ Mosher, John C. (March 3, 1934). "The Current Cinema". The New Yorker. New York: F-R Publishing: 66.

- ↑ By, D. W. (1934, Nov 25). TAKING A LOOK AT THE RECORD. New York Times (1923-Current File) Retrieved from https://search-proquest-com.ezproxy.sl.nsw.gov.au/docview/101193306?accountid=13902

- ↑ "AFI's 100 Years...100 Passions Nominees" (PDF). Retrieved 2016-08-18.

- ↑ Jones, Kenneth. Julian Ovenden's Reaper Has a Song in His Heart in Death Takes a Holiday, Premiering in NYC" Archived 2011-06-22 at the Wayback Machine.. Playbill.com, June 10, 2011.

External links

- Death Takes a Holiday at AllMovie

- Death Takes a Holiday (1934) on IMDb

- Death Takes a Holiday (1971) on IMDb

- Death Takes a Holiday on Lux Radio Theater: March 22, 1937