Deal–Grove model

The Deal–Grove model mathematically describes the growth of an oxide layer on the surface of a material. In particular, it is used to predict and interpret thermal oxidation of silicon in semiconductor device fabrication.[1] The model was first published in 1965 by Bruce Deal and Andrew Grove, of Fairchild Semiconductor.

Physical assumptions

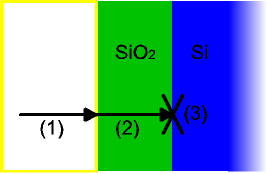

The model assumes that oxidation reaction occurs at the interface between the oxide layer and the substrate material, rather than between the oxide and the ambient gas.[1] Thus, it considers three phenomena that the oxidizing species undergoes, in this order:

- It diffuses from the bulk of the ambient gas to the surface.

- It diffuses through the existing oxide layer to the oxide-substrate interface.

- It reacts with the substrate.

The model assumes that each of these stages proceeds at a rate proportional to the oxidant's concentration. In the first case, this means Henry's law; in the second, Fick's law of diffusion; in the third, a first-order reaction with respect to the oxidant. It also assumes steady state conditions, i.e. that transient effects do not appear.

Results

Given these assumptions, the flux of oxidant through each of the three phases can be expressed in terms of concentrations, material properties, and temperature.

By setting the three fluxes equal to each other, each may be found. In turn, the growth rate may be found readily from the oxidant reaction flux.

In practice, the ambient gas (stage 1) does not limit the reaction rate, so this part of the equation is often dropped. This simplification yields a simple quadratic equation for the oxide thickness. For oxide growing on an initially bare substrate, the thickness Xo at time t is given by the following equation:

where the constants and encapsulate the properties of the reaction and the oxide layer, respectively, and the constant takes into account any initial oxide thickness present. These constants are given as:

where , with being the gas solubility parameter of the Henry's law and is the partial pressure of the diffusing gas. denotes the oxidant molecules/unit volume needed to produce a unit volume of the oxide.

Solving the quadratic equation for Xo yields:

Taking the short and long time limits of the above equation reveals two main modes of operation:

Because they appear in these equations, the quantities B and B/A are often called the quadratic and linear reaction rate constants. They depend exponentially on temperature, like this:

where is the activation energy and is the Boltzmann Constant in eV. differs from one equation to the other. The following table lists the values of the four parameters for single-crystal silicon under conditions typically used in industry (low doping, atmospheric pressure). The linear rate constant depends on the orientation of the crystal (usually indicated by the Miller indices of the crystal plane facing the surface). The table gives values for <100> and <111> silicon.

| Parameter | Quantity | Wet ( ) | Dry ( ) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Linear rate constant | <100>: 9.7 ×107 <111>: 1.63 ×108 |

<100>: 3.71 ×106 <111>: 6.23 ×106 | |

| (eV) | 2.05 | 2.00 | |

| Parabolic rate constant | 386 | 772 | |

| (eV) | 0.78 | 1.23 |

Validity for silicon

The Deal–Grove model works very well for single-crystal silicon under most conditions. However, experimental data shows that very thin oxides (less than about 25 nanometres) grow much more quickly in than the model predicts. In silicon nanostructures (e.g. Silicon Nanowires) this rapid growth is generally followed by diminishing oxidation kinetics in a process known as self-limiting oxidation, necessitating a modification of the Deal–Grove model.[1]

If the oxide grown in a particular oxidation step will significantly exceed 25 nm, a simple adjustment accounts for the aberrant growth rate. The model yields accurate results for thick oxides if, instead of assuming zero initial thickness (or any initial thickness less than 25 nm), we assume that 25 nm of oxide exists before oxidation begins. However, for oxides near to or thinner than this threshold, more sophisticated models must be used.

Deal-Grove also fails for polycrystalline silicon ("poly-silicon"). First, the random orientation of the crystal grains makes it difficult to choose a value for the linear rate constant. Second, oxidant molecules diffuse rapidly along grain boundaries, so that poly-silicon oxidizes more rapidly than single-crystal silicon.

Dopant atoms strain the silicon lattice, and make it easier for silicon atoms to bond with incoming oxygen. This effect may be neglected in many cases, but heavily doped silicon oxidizes significantly faster. The pressure of the ambient gas also affects oxidation rate.

References

- 1 2 3 Liu, M.; Peng, J.; et al. (2016). "Two-dimensional modeling of the self-limiting oxidation in silicon and tungsten nanowires". Theoretical and Applied Mechanics Letters. 6 (5): 195–199. doi:10.1016/j.taml.2016.08.002.

- Jaeger, Richard C. (2002). "Thermal Oxidation of Silicon". Introduction to Microelectronic Fabrication (2nd ed.). Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-201-44494-1.

- Deal, B. E.; A. S. Grove (December 1965). "General Relationship for the Thermal Oxidation of Silicon". Journal of Applied Physics. 36 (12): 3770–3778. doi:10.1063/1.1713945.

External links

Online Calculator including pressure, doping, and thin oxide effects: http://www.lelandstanfordjunior.com/thermaloxide.html