Dawson's Field hijackings

| Dawson's Field hijackings | |

|---|---|

| Part of Black September in Jordan and spillover of Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon | |

The airliners on the ground during the PFLP-hosted press conference. | |

| Location | Zarqa, Jordan |

| Coordinates | 32°06′21″N 36°09′24″E / 32.1059°N 36.1567°ECoordinates: 32°06′21″N 36°09′24″E / 32.1059°N 36.1567°E |

| Date | 6–13 September 1970 |

| Target | TWA 741, Swissair 100, El Al 219, Pan Am 93, BOAC 775 |

Attack type | 4 successful aircraft hijackings, 1 foiled, hostage crisis |

| Weapons | Firearms and hand grenades |

| Deaths | 1 hijacker |

Non-fatal injuries | 1 |

| Perpetrators | Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine |

| Defenders | Bar Lev, passengers and sky marshal (Flight 219) |

| Motive | Release of Palestinian prisoners imprisoned in Europe and Israel |

In September 1970, four jet airliners bound for New York City and one for London were hijacked by members of the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLP). Three aircraft were forced to land at Dawson's Field, a remote desert airstrip near Zarqa, Jordan, formerly Royal Air Force Station Zerqa, a desert airstrip, one that then became PFLP's "Revolutionary Airport". By the end of the incident, one hijacker had been killed and one injury reported. This was the second instance of mass aircraft hijacking, after an escape from communist Czechoslovakia in 1950.

- On 6 September, TWA Flight 741 from Frankfurt (a Boeing 707) and Swissair Flight 100 from Zürich (a Douglas DC-8) were forced to land at Dawson's Field.[1][2]

- On the same day, the hijacking of El Al Flight 219 from Amsterdam (another 707) was foiled: hijacker Patrick Argüello was shot and killed, and his partner Leila Khaled was subdued and turned over to British authorities in London. Two PFLP hijackers who were prevented from boarding the El Al flight, hijacked instead Pan Am Flight 93, a Boeing 747, diverting the large plane first to Beirut and then to Cairo, rather than to the small Jordanian airstrip.

- On 9 September, a fifth plane, BOAC Flight 775, a Vickers VC10 coming from Bahrain, was hijacked by a PFLP sympathizer and brought to Dawson's Field in order to pressure the British to free Khaled.

While the majority of the 310 hostages were transferred to Amman and freed on 11 September the PFLP segregated the flight crews and Jewish passengers, keeping the 56 Jewish hostages in custody, while releasing the non-Jews. Six hostages in particular were kept because they were men and American citizens, not necessarily Jews. The six men held in particular were Robert Norman Schwartz, a U.S. Defense Department researcher stationed in Bangkok, Thailand; James Lee Woods, Schwartz's assistant and security detail; Gerald Berkowitz, an American-born Jew and college chemistry professor; Rabbi Abraham Harrari-Raful and his brother Rabbi Joseph Harrari-Raful, two Brooklyn school teachers; and John Hollingsworth, a U.S. State Department employee. Schwartz, whose father was Jewish, was a convert to Catholicism.[3][4][5] On 12 September prior to their announced deadline, the PFLP used explosives to destroy the empty planes, as they anticipated a counterstrike.[1]

The PFLP's exploitation of Jordanian territory in the drama was another instance of the increasingly autonomous Arab Palestinian activity within the Kingdom of Jordan – a serious challenge to the Hashemite monarchy of King Hussein. Hussein declared martial law on 16 September and from 17 to 27 September his forces deployed into Palestinian-controlled areas in what became known as Black September in Jordan, nearly triggering a regional war involving Syria, Iraq, and Israel with potentially global consequences.

Swift Jordanian victory, however, enabled a 30 September deal in which the remaining PFLP hostages were released in exchange for Khaled and three PFLP members in a Swiss prison.[1]

Hijackings

El Al Flight 219

4X-ATB, the aircraft involved, in July 1970 | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | 6 September 1970 |

| Summary | Attempted Hijacking |

| Site | English Channel |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 707–458 |

| Operator | El Al Israel Airlines |

| Registration | 4X-ATB |

| Flight origin | Lod International Airport |

| Stopover | Amsterdam Schiphol Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy Int'l Airport |

| Passengers | 138 |

| Crew | 10 |

| Fatalities | 1 (hijacker) |

| Injuries | 1 |

| Survivors | 148 |

El Al Flight 219 (type Boeing 707, serial 18071/216, registration 4X-ATB) originated in Tel Aviv, Israel, and was headed to New York City. It had 138 passengers and 10 crew members aboard. It stopped in Amsterdam, Netherlands, and was hijacked shortly after it took off from there by Patrick Argüello,[6] a Nicaraguan American, and Leila Khaled, a Palestinian.

The original plan was to have four hijackers aboard this flight, but two were prevented from boarding in Amsterdam by Israeli security—these two conspirators, traveling under Senegalese passports with consecutive numbers,[7] were prevented from flying on El Al on 6 September. They purchased first-class tickets on Pan Am Flight 93 and hijacked that flight instead.

Posing as a married couple, Argüello and Khaled boarded the plane using Honduran passports—having passed through a security check of their luggage—and were seated in the second row of tourist class. Once the plane was approaching the British coast, they drew their guns and grenades and approached the cockpit, demanding entrance. According to Khaled, in an interview in 2000,

"So half an hour (after take off) we had to move. We stood up. I had my two hand grenades and I showed everybody I was taking the pins out with my teeth. Patrick stood up. We heard shooting just the same minute and when we crossed the first class, people were shouting but I didn't see who was shooting because it was behind us. So Patrick told me 'go forward I protect your back.' So I went and then he found a hostess and she was going to catch me round the legs. So I rushed, reached to the cockpit, it was closed. So I was screaming 'open the door.' Then the hostess came; she said 'she has two hand grenades,' but they did not open (the cockpit door) and suddenly I was threatening to blow up the plane. I was saying 'I will count and if you don't open I will blow up the plane.'"[8]

After being informed by intercom that a hijacking was in progress, Captain Uri Bar Lev decided not to accede to their demands:

"I decided that we were not going to be hijacked. The security guy was sitting here ready to jump. I told him that I was going to put the plane into negative-G mode. Everyone would fall. When you put the plane into negative, it's like being in a falling elevator. Instead of the plane flying this way, it dives and everyone who is standing falls down."[6]

Bar Lev put the plane into a steep nosedive which threw the two hijackers off-balance. Argüello reportedly threw his sole grenade down the airliner aisle, but it failed to explode, and he was hit over the head with a bottle of whiskey by a passenger after he drew his pistol. Argüello shot steward Shlomo Vider and according to the passengers and Israeli security personnel, was then shot by a sky marshal.[7] His accomplice Khaled was subdued by security and passengers, while the plane made an emergency landing at London Heathrow Airport; she then claimed that Argüello was shot four times in the back after he and Khaled failed to hijack the airplane. Vider underwent emergency surgery and recovered from his wounds; Argüello died in the ambulance taking both him and Khaled to Hillingdon Hospital. Khaled was then arrested by British police.

Nationalities on Flight 219

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 118 | 10 | 128 | |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | |

| 9 | 0 | 9 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| Total | 138 | 10 | 148 |

TWA Flight 741

A TWA Boeing 707 similar to the hijacked aircraft | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | 6 September 1970 |

| Summary | Hijacking |

| Site | Brussels, Belgium |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 707–331B |

| Operator | Trans World Airlines |

| Registration | N8715T |

| Flight origin | Lod International Airport |

| 1st stopover | Ellinikon International Airport |

| 2nd stopover | Frankfurt International Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy Int'l Airport |

| Passengers | 144 |

| Crew | 11 |

| Injuries | none |

| Survivors | 155 (all) |

TWA Flight 741 (type Boeing 707, serial 18917/460, registration N8715T[9]) was a round-the-world flight carrying 144 passengers and a crew of 11. The flight on this day was flying from Tel Aviv, Israel to Athens Greece, Frankfurt am Main, Germany, and then to New York City, and was hijacked on the Frankfurt-New York leg. In an interview for the film Hijacked, Flight 741's purser, Rudi Swinkles, recalled, "I saw a passenger running toward first class. I ran after him, and when he came to first class to the cockpit, he turned around, had a gun in his hand, and pointed the gun at me, and said, 'Get back, get back.' So right away, I dove behind the bulkhead first class divider, and I hid behind it, over here."[10]

It landed at Dawson's Field in Jordan at 6:45 p.m. local time.[11]

Hijackers gained control of the cockpit and a female stated, "This is your new captain speaking. This flight has been taken over by the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine. We will take you to a friendly country with friendly people."[5]

Yitzchok Hutner[12] and Tova Kahn and her children were also on the plane.[13]

Nationalities on Flight 741

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 16 | 2 | 18 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 55 | 0 | 55 | |

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 18 | 0 | 18 | |

| 51 | 9 | 60 | |

| Total | 144 | 11 | 155 |

Swissair Flight 100

HB-IDD, the DC-8 involved, at Zurich Airport in 1965. | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | 6 September 1970 |

| Summary | Hijacking |

| Site | Dijon, France |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Douglas DC-8-53 |

| Aircraft name | Nidwalden |

| Operator | Swissair |

| Registration | HB-IDD |

| Flight origin | Zurich Kloten Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy Int'l Airport |

| Passengers | 145 |

| Crew | 12 |

| Injuries | none |

| Survivors | 157 (all) |

Swissair Flight 100 (type Douglas DC-8-53, registration HB-IDD, named Nidwalden) built in 1963 was carrying 143 passengers and 12 crew from Zürich-Kloten Airport, Switzerland, to New York JFK. The plane was hijacked over France minutes after the TWA flight. A male and a female seized the plane, one of them having a silver revolver. An announcement was made over the intercom that the plane had been taken over by the PFLP as it was diverted to Dawson's Field, increasing the hostage number to 306 hostages. [14][15]

Nationalities on Flight 100

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 3 | 0 | 3 | |

| 25 | 0 | 25 | |

| 20 | 0 | 20 | |

| 57 | 10 | 67 | |

| 26 | 0 | 26 | |

| Other | 14 | 2 | 16 |

| Total | 145 | 12 | 157 |

Pan Am Flight 93

Boeing 747-121 (N750PA), similar to the hijacked plane in PA93. | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | 6 September 1970 |

| Summary | Hijacking |

| Site | Scotland |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Boeing 747–121 |

| Aircraft name | Clipper Fortune |

| Operator | Pan American World Airways |

| Registration | N752PA |

| Flight origin | Brussels Airport |

| Stopover | Amsterdam Schiphol Airport |

| Destination | John F. Kennedy Int'l Airport |

| Passengers | 136 |

| Crew | 17 |

| Injuries | none |

| Survivors | 153 (all) |

Pan Am Flight 93 (type Boeing 747, serial 19656/34, registration N752PA,[16] name Clipper Fortune) was carrying 136 passengers and 17 crew. The flight was from Brussels, Belgium, to New York, with a stop in Amsterdam. The two hijackers bumped from the El Al flight boarded and hijacked this flight as a target of opportunity.

In-flight director John Ferruggio recalled,

"We were ready for take off in Amsterdam, and the aircraft came to an abrupt stop in the middle of the runway. And Captain Priddy called me up into the cockpit and says, 'I'd like to have a word with you.' I went up to the cockpit, and he says, 'We have two passengers by the name of Diop and Gueye.' He says, 'Go down and try to find them in the manifest, because I would like to have a word with them.' ... So Captain Priddy sat them down at these two seats over here. He gave them a pretty good pat. They had a Styrofoam container in their groin area where they carried the grenade, and the 25-Cal. pistols. But this we found out much later."[10]

The plane first landed in Beirut, where it refueled and picked up several associates of the hijackers, along with enough explosives to destroy the entire plane. It then landed in Cairo after uncertainty whether the Dawson's Field airport could handle the size of the new Boeing 747 jumbo jet. Flight director John Ferruggio, who led the plane's evacuation, is credited with saving the plane's passengers and crew.[17] The plane was blown up at Cairo seconds after it had been evacuated.[18] An audio recording of Feruggio's landing instructions to passengers was made by one of them and can be heard in a National Public Radio report.[19] The hijackers were arrested by Egyptian police.

Nationalities on Flight 93

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25 | 0 | 25 | |

| 25 | 0 | 25 | |

| 10 | 0 | 10 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 35 | 3 | 38 | |

| 2 | 0 | 2 | |

| 23 | 14 | 37 | |

| Total | 138 | 17 | 155 |

BOAC Flight 775

.jpg) A BOAC Vickers VC10, a similar aircraft to that hijacked | |

| Hijacking | |

|---|---|

| Date | 9 September 1970 |

| Summary | Hijacking |

| Site | Persian Gulf |

| Aircraft | |

| Aircraft type | Vickers VC-10-1151 |

| Operator | British Overseas Airways Corporation |

| Registration | G-ASGN |

| Flight origin | Sahar International Airport |

| 1st stopover | Bahrain International Airport |

| 2nd stopover | Beirut International Airport |

| Destination | London Heathrow Airport |

| Passengers | 105 |

| Crew | 9 |

| Injuries | none |

| Survivors | 114 (all) |

On 9 September a fifth plane, BOAC Flight 775, a Vickers VC10 (registration G-ASGN[20]), from Bombay (now Mumbai) to London via Bahrain and Beirut was hijacked after departing Bahrain and forcibly landed at Dawson's Field. This was the work of a PFLP sympathizer who wanted to influence the British government to free Leila Khaled.

Footage of the plane taking off from Beirut for Dawson's Field is in the Pathe News archive.[21]

Nationalities on Flight 775

| Nationality | Passengers | Crew | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 15 | 0 | 15 | |

| 25 | 0 | 25 | |

| 5 | 0 | 5 | |

| 4 | 0 | 4 | |

| 25 | 9 | 34 | |

| 21 | 0 | 21 | |

| Total | 105 | 9 | 114 |

Hostage accounts

Unnamed passengers later recounted their days as hostages.

Unknown speaker 1: "I was held hostage in the front of the plane by the Arabs. They wouldn't believe that I was an American citizen, because they saw my passport that I was in Israel two weeks before. They thought I was connected with the Israeli military, and I was held at gunpoint in front of the plane."

Unknown speaker 2: "Well, then they were told that we were being hijacked to Beirut, which we, we originally were, and everyone was to remain calm and do exactly what they said."

Unknown speaker 3: "I landed at the airport, we got off, and they told the captain that we had three minutes to evacuate; but I didn't think there were still a couple of people on board when they blew the, they blew the front part of the plane up. They had dynamited the they had dynamite all over the front and the back of the plane. They brought on 20 kilos of plastic dynamite or something in Beirut."[22]

Days in the desert

On 7 September 1970, the hijackers held a press conference for 60 members of the media who had made their way to what was being called "Revolution Airport." About 125 hostages were transferred to Amman, while the American, Israeli, Swiss, and West German citizens were held on the planes.[23] Jewish passengers were also held. Passenger Rivke Berkowitz of New York, interviewed in 2006, recalled "the hijackers went around asking people their religion, and I said I was Jewish." Another Jewish hostage, 16-year-old Barbara Mensch, was told she was "a political prisoner."[5]

As groups of the remaining passengers and crew were assembled on the sand in front of the media, members of the PFLP, among them Bassam Abu Sharif, made statements to the press. Sharif claimed that the goal of the hijackings was "to gain the release of all of our political prisoners jailed in Israel in exchange for the hostages."[10][24]

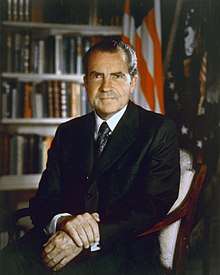

In the United States, President Richard Nixon met with his advisers on 8 September and ordered United States Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird to bomb the PFLP positions in Jordan. Laird refused on the pretext that the weather was unfavorable, and the idea was dropped. The 82nd Airborne Division was put on alert, the Sixth Fleet was put to sea, and military aircraft were sent to Turkey in preparation for a possible military strike.[25]

In contrast, British Prime Minister Edward Heath decided to negotiate with the hijackers, ultimately agreeing to release Khaled and others in exchange for hostages. This was bitterly opposed by the United States:

"Tensions between London and Washington are reflected in a bitterly acrimonious telephone conversation between top Foreign Office official Sir Denis Greenhill and senior White House aide Joseph Sisco. ... 'I think your government would want to weigh very, very carefully the kind of outcry that would occur in this country against your taking this kind of action.' Greenhill replied: 'Well, they do, Joe, but there is also an outcry in this country,' expressing concern that 'Israel won't lift a bloody finger and ... our people get killed. You could imagine how bad that would look, and if it all comes out that we could have got our people out but for the obduracy of you and other people so to speak. ... I mean people say, why the bloody hell didn't you try?'"[26]

On 9 September the United Nations Security Council demanded the release of the passengers, in Resolution 286. The following day, fighting between the PFLP and Jordanian forces erupted in Amman at the Intercontinental Hotel, where the 125 women and children were being kept by the PFLP, and the Kingdom appeared to be on the brink of full-scale civil war.[10] The destruction of the aircraft on 12 September highlighted the impotence of the Jordanian government in Palestinian-controlled areas, and the Palestinians declared the city of Irbid to be "liberated territory", in a direct challenge to Hussein's rule.

On 13 September the BBC World Service broadcast a government announcement in Arabic saying that the UK would release Khaled in exchange for the hostages.[27]

According to United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger, "At this point, whether because [American] readiness measures had given [King Hussein] a psychological lift or because he was reaching the point of desperation, Hussein resolved on an all-out confrontation with the fedayeen."[28]

Complicating the international crisis was the fact that Syria and Iraq, which had links with the USSR, had already threatened to intervene on behalf of Palestinian groups in any confrontation with the Kingdom of Jordan. According to British documents declassified under the "thirty year rule", an anxious King Hussein asked the UK and United States to pass a request to Israel to bomb Syrian troops if they entered Jordan in support of the Palestinians.[27] When a Syrian tank crossed the border, Israeli aircraft overflew the area in warning.

Resolution and consequences

King Hussein declared martial law on 16 September and initiated the military actions later known as the Black September conflict. Hostage David Raab described the Jordanian military actions:

"We were in the middle of the shelling since Ashrafiyeh was among the Jordanian Army's primary targets. Electricity was cut off, and again we had little food or water. Friday afternoon, we heard the metal tracks of a tank clanking on the pavement. We were quickly herded into one room, and the guerrillas threw open the doors to make the building appear abandoned so it wouldn't attract fire. Suddenly, the shelling stopped."[23]

About two weeks after the start of the crisis, the remaining hostages were recovered from locations around Amman and exchanged for Leila Khaled and several other PFLP prisoners. The hostages were flown to Cyprus and then to Rome's Leonardo da Vinci Airport, where on 28 September they met President Nixon, who was conducting a State visit to Italy and the Vatican.[29] Speaking to reporters that day, Nixon noted he had told the released captives that

"[A]s a result of what they had been through... the possibility of reducing hijackings in the future had been substantially increased, because the international community was outraged by these incidents. Now we have not only mobilized guards on our planes, but we are developing facilities ... for the purpose of seeing that people who might be potential hijackers do not get on planes with weapons or explosive material."[30]

During the crisis, on 11 September President Nixon initiated a program to address the problem of "air piracy", including the immediate launch of a group of 100 federal agents to begin serving as armed sky marshals on U.S. flights.[7] Nixon's statement further indicated the U.S. departments of Defense and Transportation would determine whether X-ray devices then available to the military could be moved into civilian service.[31]

The PFLP officially disavowed the tactic of airline hijackings several years later, although several of its members and subgroups continued to hijack aircraft and commit other violent operations.[32]

Documentary film

In 2006, Ilan Ziv described the Dawson's Field hijackings in Hijacked, an hour-long episode of PBS's program American Experience, which he wrote and directed and which originally aired on 26 February 2006. Ziv included archival footage of the events and interviewed hijackers, hostages, members of the media, and politicians.

References

- 1 2 3 BBC News, "On This Day: 12 September". "Hijacked jets destroyed by guerrillas". BBC News. 12 September 1970. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ Dawson's Field was named after Air Chief Marshal Sir Walter Dawson Air of Authority – A History of RAF Organisation – Air Chief Marshal Sir Walter Dawson refers

- ↑ "Britain Releases Girl Guerilla". The Palm Beach Post. 1 October 1970. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "Robert Schwartz; Defense Official Was Hostage in Hijacking". The Washington Post. 17 June 2007. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- 1 2 3 Tugend, Tom (24 February 2006). "The Day a New Terrorism Was Born". The Jewish Journal of Greater Los Angeles. Los Angeles, California: Jewish Publications. ISSN 0888-0468. OCLC 13450863. Retrieved 10 November 2007.

- 1 2 Public Broadcasting Service website for Hijacked, "The American Hijacker". Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- 1 2 3 Public Broadcasting Service, Hijacked website, "Flight crews and security". Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ Baum, Philip. Aviation Security International September, 2000. "Leila Khaled: In her own words". Archived from the original on 24 March 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ "FAA Registry (N8715T)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- 1 2 3 4 Hijacked "Transcript". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- ↑ Hijacked "Timeline and map". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ Terror in Black September: An Eyewitness Account in Middle East Forum

- ↑ Hostages Tell Concerns Spokane Daily Chronicle, 12 September 1970

- ↑ Terror in Black September: The First Eyewitness Account of the Infamous 1970 Hijackings by David Raab

- ↑ "Entführung einer Swissair-DC-8 nach Zerqa". NZZ. 2005-09-05. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- ↑ "FAA Registry (N752PA)". Federal Aviation Administration.

- ↑ Marquard, Bryan (22 June 2010). "John Ferruggio, at 84; hero of 1970 Pan Am hijacking". Boston Globe. Retrieved 27 June 2010.

- ↑ "Apollo 13". UPI. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ↑ "The Skyjacking of 1970". NPR. 9 September 2003. Retrieved 6 September 2010.

- ↑ "G-INFO Database". Civil Aviation Authority.

- ↑ "Pathe News film". Retrieved 9 May 2013.

- ↑ "1970 Year in Review—Hijackings". UPI. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- 1 2 Raab, David. The New York Times Magazine, 22 August 2004. "Remembrance of terror past". Retrieved 2 May 2006. . Reprinted at http://www.terrorinblackseptember.com

- ↑ Public Broadcasting Service, American Experience, "Hijacked:Journalists and the Hijacking". Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ Hijacked "People and events". Public Broadcasting Service. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- ↑ Davis, Douglas. The Jerusalem Post, 2 January 2001. "Declassified documents show how UK gave in to terrorists". Archived from the original on 22 May 2006. Retrieved 1 May 2006.

- 1 2 UK Confidential, 1 January 2001 "Black September: Tough negotiations". BBC News. 1 January 2001. Retrieved 2 May 2006.

- ↑ Kissinger, Henry. "Crisis and Confrontation". Retrieved 2 May 2006. . Time, 15 October 1979.

- ↑ The Richard M. Nixon Library & Birthplace, "Nixon Papers, 1970". Retrieved 5 May 2006. , PDF transcript "Exchange of remarks with released American hostages."

- ↑ The Richard M. Nixon Library & Birthplace, "Nixon Papers, 1970". Retrieved 5 May 2006. , PDF transcript Exchange of remarks with reporters at Leonardo da Vinci Airport about released American hostages. Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine. 28 September 1970.

- ↑ The Richard M. Nixon Library & Birthplace, "Nixon Papers, 1970". Retrieved 5 May 2006. , PDF transcript "Statement announcing a program to deal with Airplane hijacking Archived 3 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine." 11 September 1970.

- ↑ "On This Day, 23 February 1972: Hijackers surrender and free Lufthansa crew". BBC News. 23 February 1972. Retrieved 11 April 2011.

It later emerged the hijackers belonged to the PFLP (the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine) and had been paid ,00m in ransom.

Further reading

- Arey, James A. The Sky Pirates. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1972.

- Carlton, David. The West's Road to 9/11: Resisting, Appeasing and Encouraging Terrorism since 1970. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006. ISBN 1-4039-9608-3. Cites the Western capitulation to the Dawson's field hijackings as the beginning of the rise of modern terrorism.

- Phillips, David. Skyjack: The Story of Air Piracy. London: George G. Harrap, 1973.

- Moss, Miriam. Girl on a Plane. London: Andersen Press, 2015. A fictionalised account by Moss, who, aged 15, was a passenger on BOAC Flight 775 from Bahrain.

- Raab, David. Terror in Black September: The First Eyewitness Account of the Infamous 1970 Hijackings. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007. ISBN 1-4039-8420-4.

- Snow, Peter, and David Phillips. The Arab Hijack War: The True Story of 25 Days in September 1970. New York: Ballantine Books, 1971.

External links

- Website of Hijacked, Ilan Ziv's hour-long episode of PBS's The American Experience, originally aired 26 February 2006.

- Hijacked on IMDb

- BBC story on secret documents on this affair released after 30 years

- Aviation Security interview with Leila Khaled

- Terror in Black September website

- Bassam Abu Sharif's website with pictures of hijacked planes

- Time cover, 21 September 1970 "Pirates in the Sky"

- BBC report from Amman, September 1970

- Walter Cronkite's recollections, audio program at NPR

- Article on the exclusive filming of the destruction of the aircraft by UPITN cameraman Hassan Dalal.

- Unedited film footage from the Pathe News archive.