Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul

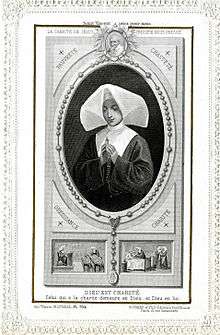

The Company of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul (Latin: Societas Filiarum Caritatis a S. Vincentio de Paulo), called in English the Daughters of Charity or Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent De Paul is a Society of Apostolic Life for women within the Catholic Church. Its members make annual vows throughout their life, which leaves them always free to leave, without need of ecclesiastical permission. They were founded in 1633 and state that they are devoted to serving Jesus Christ in persons who are poor through corporal and spiritual works of mercy.

They have been popularly known in France as "the Grey Sisters" from the color of their traditional religious habit, which was originally grey, then bluish grey. The 1996 publication The Vincentian Family Tree presents an overview of related communities from a genealogical perspective.[1] They use the initials DC after their names. In the past, when they were known simply as the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph, the postnominals SC were used.

In 2018 the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry found that there had been widespread historical child abuse at orphanages run by the Daughters at Smyllum Park (closed in 1981) and Bellevue House (closed in 1961).[2]

Foundation

The institute was founded by Saint Vincent de Paul, a French priest, and Saint Louise de Marillac, a widow. The need of organization in work for the poor suggested to de Paul the forming of a confraternity among the women of his parish in Châtillon-les-Dombes. It was so successful that it spread from the rural districts to Paris, where noble ladies often found it hard to give personal care to the needs of the poor. The majority sent their servants to minister to those in need, but the work was often slighted as unimportant. Vincent de Paul remedied this by referring young women who inquired about serving persons in need to go to Paris and devote themselves to this ministry under the direction of the Ladies of Charity. Marguerite Naseau, a 34-year-old woman from the countryside in Suresnes, met Vincent de Paul with other priests of the Congregation of the Mission during one of his Missions of Evangelization. In 1630 she met up with Vincent and Louise in Paris, where they suggested that she help the Ladies of Charity.[3]

These young women formed the nucleus of the Company of the Daughters of Charity now spread over the world. On 29 November 1633, the eve of St. Andrew, de Marillac began a more systematic training of the women, particularly for the care of the sick. The sisters lived in community in order to better develop the spiritual life and thus, more effectively, carry out their mission of service. The Daughters of Charity differed from other religious congregations of that time in that they were not cloistered. They maintained the necessary mobility and availability and lived among those whom they served.[3] From the beginning, the community motto was: "The charity of Christ impels us!"

The newly formed Daughters of Charity set up soup kitchens, organized community hospitals, established schools and homes for orphaned children, offered job training, taught the young to read and write, and improved prison conditions. The hospital of St John the Evangelist in the province of Angers was the first hospital entrusted to the care of the Daughters of Charity.[4] Louise de Marillac and Vincent de Paul both died in 1660, and by this time there were more than forty houses of the Daughters of Charity in France, and the sick poor were cared for in their own dwellings in twenty-six parishes in Paris.

French Revolution

Anticlerical forces in the French Revolution were determined to shut down all convents. In 1789 France had 426 houses; the sisters numbered about 6000 in Europe. In 1792, the sisters were ordered to quit the motherhouse; the community was officially disbanded in 1793.[5] An oath to support the Revolution was imposed on all former members of religious orders who performed a service that was remunerated by the state. Taking this oath was seen as breaking off with the Church while those who refused to do so were considered counter-revolutionaries.

In Angers, revolutionary authorities decided to make an example of sisters Marie-Anne Vaillot and Odile Baumgarten in order to demonstrate what refusal to take the oath would mean. In early 1794 they faced a public execution. At a ceremony in Rome on 19 February 1984 Pope John Paul II beatified ninety-nine persons who died for the faith in Angers, including Vaillot and Baumgarten.[4] Their feast day is February 1.

Sister Marguerite Rutan was Superior of the community that staffed the hospital at Dax. The six sisters had refused to take the revolutionary oath. The Revolutionary committee wanted to remove the Superior of the Sisters and looked for a motive to arrest her. A false testimony allowed them to say that Sr. Marguerite was unpatriotic, a fanatic against the principles of the Revolution and that she tried to convince the wounded soldiers to desert and join the royalist army of Vendéens. On April 9, 1794 Sister Marguerite Rutan was condemned to death and guillotined at Poyanne Place not far from the prison.[3] She was beatified Sunday, June 19, 2011 in Dax, France. Her feast day is June 26.

Sisters Marie-Madeleine Fontaine, Marie-Françoise Lanel, Thérèse Fantou, Jeanne Gérard from the House of Charity in Arras were guillotined in Cambrai June 26, 1794. Waiting for the cart to take them to the guillotine, the guards took their chaplets and, not knowing what to do, put them on their heads like a crown. They were beatified on June 13, 1920. Their feast day is June 26.[3]

The order was restored in 1801, many former sisters returned, and it grew very rapidly throughout the 19th century.

Growth

From that time and through the 19th century, the community spread to Austria, Australia, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Portugal, Turkey, Britain and the Americas.[5] During this period, the ministry of the Daughters developed to caring for others in need such as orphans and those with physical disabilities.

The first house in Ireland was opened in Drogheda, in 1855. By 1907 there were 46 houses and 407 sisters in England; 13 houses and 134 sisters in Ireland; 8 houses and 62 sisters in Scotland. They operated 23 orphanages; 7 industrial schools; 24 public elementary schools; 1 normal school to train teachers; 3 homes for working girls or women ex-convicts; and 8 hospitals.[5]

The Convent of Saint Vincent de Paul was the first building established on Mamilla Street in Jerusalem, near Jaffa Gate, in 1886. Precipitating the future growth of that street as a commercial thoroughfare, the sisters put up a series of shops in front of the building and used the rent money for convent operations.[6] The convent was integrated into the design of the Mamilla Mall pedestrian promenade, which opened in 2007.[7]

The motherhouse of the Daughters of Charity is located at 140 rue du Bac, in Paris, France. The remains of de Marillac and those of St. Catherine Labouré lie preserved in the chapel of the motherhouse. Labouré was the Daughter of Charity to whom, in 1830, the Blessed Virgin Mary is said to have appeared, commissioning her to spread devotion to the Medal of Mary Immaculate, commonly called the Miraculous Medal.

The traditional habit of the Daughters of Charity was one of the most conspicuous of Catholic Sisters, as it included a large starched cornette on the head. This was the dress of peasant women of the neighborhood of Paris at the date of the foundation, a grey habit with wide sleeves and a long grey apron. The head-dress was at first a small linen cap, but to this was added in the early days the white linen cornette. At first it was used only in the country, being in fact the headdress of the Ile de France district, but in 1685 its use became general. The institute adopted a more simple modern dress and blue veil on 20 September 1964.

Charism

The Charism of a religious society is the characteristic impetus which distinguishes it from other similar groups. Religious communities frequently describe it as a grace or gift given by God as inspiration to the founder, which lives on in the organization. The charism of the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul is that of service to the poor.[8]

United States

In the United States, St. Elizabeth Ann Seton, a recent convert to the Catholic Church, had hoped to establish a community of Daughters of Charity. Unable to do so because of the political situation during the Napoleonic Wars, on 31 July 1809, she founded the Sisters of Charity of St. Joseph at Emmitsburg, Maryland. The nucleus of the little community consisted of five Sisters who were soon joined by others. Her desire to consecrate her life to works of charity led Mother Seton to request the Rules of the Daughters of Charity founded by St. Vincent de Paul in 1633. Bishop Benedict J. Flaget presented the request to superiors in Paris and in 1810 brought to Mother Seton the Rules by which she guided her community during her lifetime. At the time of her death in 1821, the community numbered fifty Sisters. In 1850, the community at Emmitsburg affiliated with the Mother House of the Daughters of Charity in Paris and at that time adopted the blue habit and the white collar and cornette.[9] The community in Emmitsburg became the first American province of the Daughters of Charity.

By then, other communities had been established elsewhere in the United States. In 1817, Mother Seton sent three Sisters to New York at the invitation of Bishop Connolly to open a home for dependent children. Their services were urgently needed, for many parents were victims of the epidemics that frequently invaded the city, where there was as yet no system of sanitation. In 1846, the New York congregation incorporated as a separate order, the Sisters of Charity of New York. The Sisters in New York retained the rule, customs, and spiritual exercises established by Mother Seton, and her black habit, cape and cap.[9]

During the American Civil War, the order provided nursing services to soldiers in field hospitals and in depots for prisoners of war.[10]

The Spanish–American War of 1898, quickly demonstrated the important need for trained nurses as hastily constructed army camps for more than twenty-eight thousand members of the regular army were devastated by diarrhea, dysentery, typhoid fever, and malaria—all of which took a much greater toll than did enemy gunfire. The United States government called for women to volunteer as nurses. Thousands did so, but few were professionally trained. Among the latter were 250 Catholic nurses, most of them from the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. Reverend Mother Mariana Flynn, head of the Daughters of Charity, recalled their service during the Civil War and said her sisters were proud to be "back in the army again, caring for our sick and wounded."[11]

In 1910, the jurisdiction of Emmitsburg was divided into two Provinces with the Eastern Provincial House in Emmitsburg and the Western Provincial House in Normandy, Missouri, a suburb of St. Louis.[9]

Contemporary status

As of 2017, 18,000 serve in ninety-four countries, addressing needs of food, water, sanitation and shelter; and through their sustaining works including health care, HIV/AIDS, migrant and refugee assistance, and education.[12]

In July 2011 the Daughters of Charity merged four of the five existing U.S. provinces — Emmitsburg, Maryland; Albany, New York; St. Louis, Missouri; and Evansville, Indiana. The process of unification began at a 2007 gathering in Buffalo, N.Y. The Province of the West, based in Los Altos Hills, Calif., was not involved in the merger. The newly constituted province is named for St. Louise de Marillac, who founded the congregation in France in 1633 along with St. Vincent de Paul to “serve Christ in persons who are poor.” Administrative offices for the Province of St. Louise are located in St. Louis, Mo. The archival collections of the former provinces will be consolidated in a new facility located within the former St. Joseph’s Provincial House, adjacent to The Basilica of the National Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton and the Seton Heritage Center, in Emmitsburg, Maryland.[13] The new province covers 34 states, the District of Columbia and the Canadian province of Quebec.

Activities

Many hospitals, orphanages, and educational institutions were established and operated by the Daughters of Charity over the years, including Saint Joseph College, Emmitsburg, Maryland, Marillac College in Missouri, Santa Isabel College Manila, Saint Louise's Comprehensive College in Belfast, Northern Ireland, and Saint Louise de Marillac High School in Illinois. Though no longer staffed and run by the Daughters, five of the hospitals which were founded by them in the USA continue to operate within the St. Vincent's Health Care System.[14]

In Mayagüez, Puerto Rico they help run the Asilo De Pobres[15] and in the Philippines they run the College of the Immaculate Conception.

In the United Kingdom, the Daughters of Charity are based at Mill Hill, north London, and have registered charity status.[16]

Daughters operate St. Ann's Infant and Maternity Home near Washington, D.C.[17]

Child abuse

In April 2017 it was announced that the second phase of the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry would focus on orphanages run by the Daughters of Charity: Smyllum Park in Lanark, Bellevue House in Rutherglen, St Joseph's Hospital in Rosewell, St Vincent's School for the Deaf/Blind in Glasgow and Roseangle Orphanage (St Vincent's) in Dundee.[18]

In September 2017, an investigation by BBC File on 4 and the Sunday Post revealed evidence that the bodies of up to 400 children from Smyllum Park had been buried in a mass grave. The orphanage looked after 11,600 children between 1864 and 1981. The investigation followed on from the discovery in 2003 of an unmarked burial plot in St Mary's cemetery, by campaigners searching for evidence of physical abuse which they believed many former residents had experienced. In addition to burial records examined in 2003 which reported that some children had died of malnutrition, the 2017 investigation uncovered allegations of abuse including beatings, punches, public humiliations and psychological abuse.[19] A former resident at the home told BBC Stories of her own experiences of "systematic abuse" including an incident in which her arm was broken by a nun who discovered her being sexually abused by a priest. She stated "every child was beaten, punished, locked in a dark room, made to eat their own vomit and I would say that most of us had our mouths rinsed out with carbolic soap."[20] Two representatives of the Daughters of Charity had given evidence to the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry earlier in 2017, claiming that they could find no records of any abuse taking place.[19] Following investigation by Police Scotland into the mass burial site, The Crown Office acknowledged the level of public concern but said there was currently no evidence of criminal activity. In response to questions asked in the Scottish Parliament, childcare minister Mark McDonald confirmed that at the time of the deaths there was no requirement for private burial authorities to keep a register of burial plots.[21][22]

In August 2018 police arrested and charged nuns and other former staff of Smyllum Park, eleven women and a man, regarding alleged child physical and sexual abuse; enquiries continued.[23]

In October 2018 the Scottish Child Abuse Inquiry found children at Smyllum Park orphanage were abused sexually and beaten with leather straps, hairbrushes and crucifixes. The children experienced "no love, no compassion, no dignity and no comfort." The inquiry report states that:

- Children were sexually abused in Smyllum. Children were sexually abused by priests, a trainee priest, Sisters, members of staff and a volunteer.

- There was also problematic sexual behaviour by other children.

- Children were physically abused. They were hit with and without implements, either in an excess of punishment or for reasons which the child could not fathom.

- The implements used included leather straps, the "Lochgelly Tawse," hairbrushes, sticks, footwear, rosary beads, wooden crucifixes and a dog's lead.

- For some children, being hit was a normal aspect of daily life.

- The physical punishments meted out to children went beyond what was acceptable at the time whether as punishment in schools or in the home.

- Children who were bed-wetters were abused physically and emotionally.

- They were beaten, put in cold baths and humiliated in ways that included "wearing" their wet sheets and being subjected to hurtful name-calling by Sisters and by other children.

- Many children were force-fed.[2]

The Daughters of Charity responded that the events and practices described were not in accordance with their values, and that they would give the report "our utmost attention". They apologised to anyone who suffered abuse while in their care.

Members proposed for Sainthood

- Saint Louise de Marillac

- Saint Catherine Laboure

- Saint Elizabeth Ann Seton

- Saint Jeanne Antide Thouret

- Blessed Odile Baumgarten

- Blessed Rosalie Rendu

- Blessed Marta Anna Wiecka

- Blessed Lindalva Justo de Oliveira

- Blessed Giuseppina Nicoli

- Servant of God Asuncion Ventura

- Servant of God Maria Josefa Brandis (Leopoldina) (1815-1900)

- Servant of God Teresa Borgarino (Gabriela) (1880-1947)

- Servant of God Teresa Tambelli (1884-1964)

- Servant of God Francisca Benicia Oliveira (Clemência) (1896-1966)

- Servant of God Justa Dominguez de Vidauretta Idoy

- Servant of God Pia Cantalupo (Anna)

- Servant of God Barbara Samulowska (Stanislawa)

- Servant of God Marie de Mandat-Grancey

- Sister Ursula Mattingly

- Marie-Therese Marquet (Elisabeth)

- Marie-Josephe Adam (Josephine)

- Maria Clorinda Andreoni (Vittoria)

- Marie-Anne Pavillon (Eugenie) and 6 Companions

References

- ↑ McNeil, Betty Ann (1996). The Vincentian Family Tree: A Genealogical Study. Chicago: Vincentian Studies Institute.

- 1 2 Child abuse inquiry says orphanages were places of 'threat and abuse'

- 1 2 3 4 "Origin of the Company, Les Filles de la Charité de Saint Vincent de Paul". Filles-de-la-charite.org. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- 1 2 "Davitt CM, Thomas. "Martyred Daughters of Charity", Vincentian Online Library". Famvin.org. 1984-02-19. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- 1 2 3 "CATHOLIC ENCYCLOPEDIA: Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul". www.newadvent.org.

- ↑ Wager, Eliyahu (1988). Illustrated Guide to Jerusalem. The Jerusalem Publishing House, Ltd. pp. 169–170.

- ↑ Furstenberg, Rochelle (2014). "Israel Life: Old-New Mall". Hadassah Magazine. Retrieved 23 August 2014.

- ↑ "Charism Alive", Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul West Central Province Archived 2013-04-11 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 "A Short History of the Sisters of Charity, Emmitsburg Area Historical society". Emmitsburg.net. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ McNeil, Betty Ann; Maher, Mary Denis; Bucklew, Janet Leigh (2015). Balm of Hope: Charity Afire Impels Daughters of Charity to Civil War Nursing. DePaul University Vincentian Studies Institute. ISBN 9781936696086. OCLC 922894915.

- ↑ Mercedes Graf, "Band Of Angels: Sister Nurses in the Spanish–American War," Prologue (2002) 34#3 pp 196–209. online

- ↑ "Who We Are". Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent De Paul. Retrieved 20 September 2017.

- ↑ ""Historical Archives", The National Shrine of St. Elizabeth Ann Seton". Setonheritage.org. Archived from the original on 2013-09-30. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ "STVHS". St Vincent's Health System. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ "Obras de Asistencia Social y Parroquial" (in Spanish). Hijas de la Caridad. Archived from the original on 2009-10-26. Retrieved September 15, 2017.

- ↑ Charity Commission. Charity For Roman Catholic Purposes Administered In Connection With The Sisters Of Charity Of St Vincent De Paul, registered charity no. 236803.

- ↑ "St. Ann's Infant and Maternity Home website - Mission". Stanns.org. Retrieved 2014-03-03.

- ↑ "Child abuse inquiry to focus on Catholic Church homes". STV News. 6 April 2017. Retrieved 10 September 2017.

- 1 2 Robinson, Ben; Buchanan, Michael (10 September 2017). "Bodies of 'hundreds' of children buried in mass grave". BBC News.

- ↑ "'I was abused by nuns for a decade' at Smyllum Park". BBC News. 15 September 2017.

- ↑ "'No evidence of crime' at orphanage where 400 children's bodies buried in mass grave". Evening Times (Glasgow). 12 September 2017. Retrieved 14 September 2017.

- ↑ "'No crime' over orphanage mass grave". BBC News. 12 September 2017.

- ↑ "Nuns charged in investigation into child abuse at Smyllum Park". The Guardian. 23 August 2018. Retrieved 23 August 2018.

See also

Further reading

- Martha M. Libster & Sister Betty Ann McNeil. Enlightened Charity: The Holistic Nursing Care, Education, and Advices Concerning the Sick of Sister Matilda Coskery, 1799 - 1870.(Golden Apple Publications, 2009)

- Susan E. Dinan, Women and Poor Relief in Seventeenth-Century France. The Early History of the Daughters of Charity (Ashgate, 2006)

- Mary Olga McKenna. Charity Alive: Sisters of Charity of Saint Vincent De Paul, Halifax 1950-1980 (1998) in Canada excerpt and text search

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Company of the Daughters of Charity of Saint Vincent de Paul. |