Danny Kirwan

| Danny Kirwan | |

|---|---|

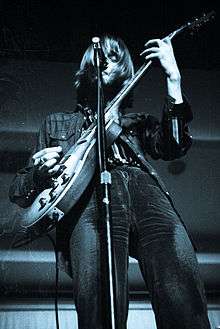

Kirwan performing with Fleetwood Mac, 18 March 1970 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Daniel David Kirwan |

| Born |

13 May 1950 Brixton, London, UK |

| Died |

8 June 2018 (aged 68) London |

| Genres | |

| Occupation(s) |

|

| Instruments |

|

| Years active | 1966–1979 |

| Labels | |

| Associated acts |

|

Daniel David Kirwan (13 May 1950 – 8 June 2018) was a British musician whose greatest success came with his role as guitarist, singer and songwriter with the blues rock band Fleetwood Mac between 1968 and 1972. He released three albums as a solo artist from 1975 to 1979, recorded albums with Otis Spann, Chris Youlden, and Tramp, and worked with his former Fleetwood Mac colleagues Jeremy Spencer and Christine McVie on some of their solo projects.

Biography

Early career

Kirwan was born Daniel David Langran in Brixton, South London.[1] His mother, Phyllis Rose Langran, married Aloysious James Kirwan in 1958 when Danny was eight.[2] Little is known about his upbringing,[3] but his guitar skills attracted attention at an early age. He was an accomplished self-taught guitarist who had been influenced by Hank Marvin of the Shadows, French gypsy guitarist Django Reinhardt and particularly by Eric Clapton's playing in the Bluesbreakers.[4] He was only 17 when he came to the attention of established British blues band Fleetwood Mac while playing in London with his first band, Boilerhouse,[3] a three-piece with Trevor Stevens on bass guitar and Dave Terrey on drums.[5] He persuaded Fleetwood Mac's producer Mike Vernon to watch Boilerhouse rehearse in a South London basement boiler-room, after which Vernon informed Fleetwood Mac founder Peter Green of his discovery. Green was impressed by Kirwan's guitar playing and subtle vibrato and thought he sounded like blues player Lowell Fulson.[6] Boilerhouse began playing support slots for Fleetwood Mac at London venues such as John Gee's Marquee Club in Wardour Street, which gave Kirwan and Green the opportunity to jam together and get to know each other.[7]

Green took a managerial interest in Boilerhouse but Stevens and Terrey were not prepared to turn professional, so Green put an advert in Melody Maker to find another rhythm section to back Kirwan. Over 300 hopefuls were said to have applied, but none was deemed good enough by the hard-to-please Green,[4] so another solution was found. Fleetwood Mac had been constituted as a quartet, but Green had been looking for another guitarist to share some of the workload in view of slide guitarist Jeremy Spencer's unwillingness to contribute much to Green's songs.[8] Drummer Mick Fleetwood, previously a member of John Mayall & the Bluesbreakers, suggested to Green that Kirwan could join Fleetwood Mac. Although Green, bassist John McVie (both also former members of the Bluesbreakers) and Spencer were not entirely convinced,[9] Fleetwood asked Kirwan to join the band in August 1968, "much to his astonishment and delight".[10][11] Fleetwood said Green had been looking for a new musical collaborator, "which is how Danny Kirwan came into our lives... Danny was a huge fan of Peter's. He would see us every chance he got, usually watching in awe from the front row. Gradually he became Peter's protégé... Peter, John and I went to see Danny's band a few times and it was clear that he needed to be with better players. In the end we just invited him to join us."[12][6] Kirwan's arrival expanded Fleetwood Mac to a five-piece with three guitarists.

Kirwan played his first gig with the band on 14 August 1968 at the Nag's Head Blue Horizon Club in Battersea, London.[9] Bob Brunning, Fleetwood Mac's first bass player, said Peter Green had been looking for ways to extend the band and perhaps change its direction. Green wanted to open out Fleetwood Mac's approach to other musical styles and bring more original material into the show.[13] Brunning thought Kirwan was the ideal foil for Green's new approach. "He played gentle, supportive rhythm guitar to Peter and Jeremy's fiery solo work and introduced vocal harmonies to some of the songs."[13] Fleetwood said, "Danny's style of playing complemented Peter's perfectly because he was already a disciple. Danny and Peter were a natural fit... Danny's sense of melody on rhythm guitar really drew Peter out, allowing him to write songs in a different style."[12] He remembered, "Danny worked out great from the start... He was an exceptional guitar player. His playing was always very melodic and tuneful, with lots of bent notes and vibrato. Playing live, he was a madman."[6] Fleetwood Mac biographer Leah Furman commented, "Danny provided a perfect sounding board for Peter's ideas, added stylistic texture, and moved Fleetwood Mac away from pure blues."[14]

Kirwan was interviewed by the British weekly music paper Melody Maker soon after joining Fleetwood Mac and gave the first indication of the breadth of his musical influences. He told Melody Maker, "I'm not keen on blues purists who close their ears to all other forms of music. I like any good music, particularly the old big band-type things. Django Reinhardt is my favourite guitarist, but I like any music that is good, whether it is blues, popular or classical."[13] The band's manager, Clifford Davis, remembered Kirwan as "a very bright boy with very high musical standards. When we were on the road he was constantly saying 'Come on, Clifford, we must rehearse, we must rehearse, we've got to rehearse.'" Davis said Kirwan "was the originator of all the ideas regarding harmonies and the lovely melodies that Fleetwood Mac would eventually encompass."[4] Peter Green described Kirwan as "a clever boy who got ideas for his guitar playing by listening to all that old-fashioned roaring twenties big-band stuff."[15] Kirwan was known to be "emotionally fragile", according to the British newspaper The Guardian, and Green said that in the early days, Kirwan "was so into it that he cried as he played".[15][3]

Fleetwood Mac

Kirwan's first recorded work with the band was his contribution of a second guitar part to Green's instrumental hit single "Albatross", which hit the top of the UK record charts in December 1968. Green later said "I would never have done 'Albatross' if it wasn't for Danny. I would never have had a number one hit record."[9] The B-side of the single was Kirwan's first published tune, the instrumental "Jigsaw Puzzle Blues". This was an old clarinet piece, written by Joe Venuti and Adrian Rollini and recorded by the Joe Venuti / Eddie Lang Blue Five in 1933. Kirwan worked out the piece from the record [16] and adapted it for himself and Green to play on guitar, but Green remembered, "I couldn't do it properly… My style wasn't all that satisfactory to Danny, but his style wasn't all that satisfactory to me." So Kirwan played all the guitar parts himself.[9]

In early January 1969 Kirwan was on his first tour of the United States with Fleetwood Mac, the band's second, and they opened for Muddy Waters at the Regal Theatre in Chicago. Producer Mike Vernon heard that Chess Records was about to close its famous Chicago studio and suggested recording a Fleetwood Mac blues album there, in the home of Chicago blues, before it disappeared.[6] He and Marshall Chess arranged a two-day recording session in which Kirwan, along with Green, Spencer, McVie and Fleetwood, played with legendary black blues musicians David 'Honeyboy' Edwards, Walter 'Shakey' Horton, J.T.Brown, Willie Dixon, Otis Spann, Buddy Guy and S.P.Leary. The session was judged "a great success" and was released by Mike Vernon in December 1969 as a double album on the Blue Horizon label, originally entitled 'Blues Jam at Chess' and later reissued as Fleetwood Mac in Chicago.[17] Two of Kirwan's songs, "Talk With You" and "Like It This Way", were included on the album. Fleetwood said later that the sessions had produced some of the best blues the band had ever played and, ironically, the last blues that Fleetwood Mac would ever record.[6]

Kirwan's skills came further to the forefront on the mid-1969 album Then Play On. The songwriting and lead vocal duties were split almost equally between Kirwan and Green, with many of the performances featuring their dual lead Gibson Les Paul guitars. Fleetwood said that Kirwan, asked to write his first songs for the band, "approached his assignment very cerebrally, much as Lyndsey Buckingham would do later, and came up with some very good music."[6] Since Spencer hardly played on the album, Kirwan had a significant role in the recording. His "Coming Your Way" opened Side 1 and his varied musical influences are evident throughout, from the flowing instrumental "My Dream" to the 1930s-style "When You Say", which Green had earmarked to be a single until his own composition "Oh Well" took shape and was chosen instead.[9]

The UK release of Then Play On featured two extra earlier Kirwan recordings, the sad blues "Without You" and the heavy "One Sunny Day", which was later covered by American blues musician Tinsley Ellis on his 1997 album Fire It Up. The US-only release English Rose from the same era included these two songs, plus the tense blues "Something Inside of Me" and "Jigsaw Puzzle Blues", both also dating from earlier sessions.Then Play On reached number 5 in the UK album charts and was the band's first album to sell more than 100,000 in America.[6]

The US track-listing of Then Play On was reordered to allow the inclusion of the full nine-minute version of Green's hit single "Oh Well", and two of Kirwan's songs, "My Dream" and "When You Say", were dropped. Only "Coming Your Way", the wistful "Although the Sun Is Shining" and his duet with Green, "Like Crying", appeared on all the later non-UK vinyl releases. On the 1990 CD release Kirwan's two dropped songs were reinstated, although "One Sunny Day" and "Without You" were now absent from releases in all territories, including the UK. The 2013 CD release restored the original UK track order, with "Without You" and "One Sunny Day" included.

Archival packages from this era, such as the Vaudeville Years and Show-Biz Blues double sets, include many more Kirwan songs and show his blues influences as well as the more arcane tastes that led to songs like "Tell Me from the Start", which could have been mistaken for a song by the 1920s-style group The Temperance Seven. Such unusual musical interests prompted band leader Green to dub Kirwan "Ragtime Cowboy Joe".[9]

Fleetwood Mac's hit singles from 1969 to 1970 were all written by Green but Kirwan's style showed through, thanks to Green's increasing desire not to act as the band's main focus. Kirwan joined Green in the dual guitar harmonies on "Albatross" and took the solo on "Oh Well Pt. 1". The final hit single from this line-up, "The Green Manalishi", was recorded in a difficult session, after Green had announced he was leaving the band. Producer Martin Birch recalled Green growing increasingly frustrated at the results of the session, but that Kirwan reassured him that they would stay there all night until they got it right.[9]

The B-side of "The Green Manalishi" was the instrumental "World in Harmony", the only track ever given a "Kirwan/Green" joint songwriting credit. Jeremy Spencer recalled that Kirwan and Green had begun to piece their guitar parts together "almost like orchestrally layered guitar work", something in which Spencer was not interested.[15] Kirwan and Green had already worked on melodic twin guitar demos that had sparked rumours in the music press in late 1969 of a duelling guitars project, although ultimately nothing came of it.[9]

Despite the closeness of their musical partnership, Kirwan and Green did not always get on well personally, at least partly due to Kirwan's short temper.[15] Although Kirwan had high musical standards and concentrated more on rehearsing than the other members of the band, with Green recalling that Kirwan always had to arrive anywhere an hour early,[9] Green was more talented when it came to improvisational skills.[15] Roadie Dennis Keane suggested that the success of "Albatross" and the follow-up single "Man of the World" went to Kirwan's head and he became more confident, to the point of trying to pressure Green and compete with him.[9] However, others, like producer Martin Birch, remember that Kirwan was often seeking reassurance from Green and that he was always in awe of him: "I often got the impression that Danny was looking for Peter's approval." [9]

After rumours in the music press in early 1970 that Kirwan would leave Fleetwood Mac, it was Green who left in May of that year. Kirwan later said that he was not surprised at his departure. "We played well together but we didn't get on. I was a bit temperamental, you see."[9] Brunning said Green left because of personality clashes with Kirwan and musical and personal differences with the other members of the band. He said Green wanted to be free to play with other musicians and not be tied down to a particular musical format.[18]

Sessions away from Fleetwood Mac

In January 1969 Kirwan made his first musical appearance outside Fleetwood Mac when he contributed to Otis Spann's blues album The Biggest Thing Since Colossus, along with Green and McVie. After Then Play On had been completed, Kirwan worked on Christine McVie's first solo album, titled Christine Perfect. (McVie was then still using her maiden name.) She included a version of Kirwan's "When You Say" on the album, which was chosen as a single, with Kirwan arranging the string section and acting as producer.[19]

Kirwan also worked on the first solo album from a then-current member of Fleetwood Mac when Jeremy Spencer released his album Jeremy Spencer in 1970. Kirwan played rhythm guitar and sang backing vocals throughout. The album was not commercially successful, but Spencer discovered that he and Kirwan worked well together without Green. He said later, "In retrospect, one of the most enjoyable things was working with Danny on it, as it brought out a side of him I hadn't seen."[20]

Kirwan also contributed as a session guitarist with the blues band Tramp on their album Tramp (1969). After he left Fleetwood Mac, Kirwan worked with Tramp again on their second album, Put a Record On (1974), and also with Chris Youlden of Savoy Brown on his solo album Nowhere Road (1973).

Kiln House

After Green left in 1970 the band considered splitting up,[21] but they continued briefly as a four-piece before recruiting keyboard player Christine McVie. Kirwan and Spencer handled the guitars and vocals together on the Kiln House album, released in the summer of that year, and continued the working relationship they had started during the recording of Spencer's solo album the previous year.[20]

Kirwan's songs on the album included "Station Man", co-written with Spencer and John McVie, which became a live staple into the post-1974 Buckingham-Nicks era. His other songs were "Jewel-Eyed Judy", dedicated to a friend of the band, Judy Wong; the energetic "Tell Me All the Things You Do", and "Earl Gray", an atmospheric instrumental which Kirwan largely composed while Peter Green was still in the band.[9] Kirwan also sang distinctive backing vocals on some of Spencer's numbers, such as the 1950s-flavoured album opener "This Is the Rock".

Other Kirwan compositions from the second half of 1970, such as those which eventually surfaced in the 2003 Madison Blues CD box set, included "Down at the Crown". The lyrics of this referred to a pub down the lane from the communal band house, 'Benifold', in Headley, Hampshire. The unsuccessful single "Dragonfly", recorded late in the year, was also written by Kirwan and included lyrics adapted from a poem by W. H. Davies. Peter Green said of "Dragonfly", "The best thing he ever wrote... that should have been a hit."[10] This was not to be the last time Kirwan used a poem as lyrics for a song, and may have been a solution to Kirwan's apparent occasional lack of inspiration when writing lyrics.[20] The B-side of the single, "The Purple Dancer", was written by Kirwan, Fleetwood and John McVie and uniquely featured Kirwan and Spencer duetting on lead vocals.

Kirwan and Bob Welch

Two tours of the USA followed in support of Kiln House, but the second, in early 1971, was blighted by Spencer's bizarre departure from the group. He disappeared in Los Angeles on the afternoon of the second gig of the tour,[12] and after several days of searching was discovered to have joined the religious cult the Children of God. After an uncomfortable time completing the remaining six weeks of the tour without him, during which Peter Green stood in as a temporary band member and each night's show consisted of "Black Magic Woman" followed by ninety minutes of Green jamming free-form with Kirwan and the rest of the band,[22] Californian Bob Welch was recruited to replace Spencer, without an audition, after a brief period of getting to know him.[21] Fleetwood said, "We tried a few others, but Bob was the perfect fit.[23] We loved his personality. His musical roots were in R&B instead of blues [and] we thought it would be an interesting blend."[6]

Welch's contrasting attitudes towards Kirwan – on one hand their difficult personal relationship, and on the other Welch's respect for Kirwan's musicianship – were a point of focus during the 18 months they were together in Fleetwood Mac. In 1999 Welch said, "He was a talented, gifted musician, almost equal to Pete Green in his beautiful guitar playing and faultless string bends."[24] In a later interview Welch said: "Danny wasn't a very lighthearted person, to say the least. He probably shouldn't have been drinking as much as he did, even at his young age.... He was always very intense about his work, as I was, but he didn't seem to ever be able to distance himself from it.... and laugh about it. Danny was the definition of 'deadly serious'." [25] Welch added, "I thought he was a nice kid, but a little bit paranoid, a little bit disturbed. He would always take things I said wrongly... He would take offence at things for no reason. I thought it was just me, but as I got to know the rest of the band, they'd say 'Oh yes, Danny, a little... strange.'"[26]

On the last two Fleetwood Mac albums which featured Kirwan, his songs occupied about half of each album. His guitar work was also evident on songs written by Welch and McVie, as they developed their own songwriting techniques. Future Games, released in September 1971, was a departure from the previous album with the clear absence of Spencer and his 50s rock 'n' roll parodies. Welch brought a couple of new songs, notably the lengthy title track, which featured both guitarists playing long instrumental sections. Welch said later, "I mostly did the rhythm guitar parts. Danny and I worked together pretty well."[27] Kirwan contributed the opener "Woman of 1000 Years" which, according to one unknown critic at the time, "floated on a languid sea of echo-laden acoustic and electric guitars".[28] His other songs were the melodic "Sands of Time", which Warner Brothers chose as a single in the USA, and the country-flavoured "Sometimes" which suggested the route he would later take during his solo career. Kirwan's influence can also clearly be heard on the two Christine McVie songs, "Morning Rain" and "Show Me a Smile". McVie later said that "Woman of 1000 Years" and "Sands of Time" were "killer songs".[29]

Future Games sold well in America. Fleetwood Mac were given top billing at the Fillmore East and broke house records for sellouts at other venues.[6] The band began an 11-month tour of America and Europe, opening a couple of dozen gigs for Deep Purple and for several months playing second on the bill to Savoy Brown.[6] In a rare week off, early in 1972,[6] they returned to London and recorded their next album, Bare Trees, in a few days. Fleetwood said the songs on the album reflected the band's "jaded road-weariness and longing for home."[6] Christine McVie wrote in "Homeward Bound", "I don't want to see another airline seat or another hotel room." The pressure and strain of life on the road, of constant travelling and performing, particularly affected Kirwan. As the tour progressed he became withdrawn and isolated from the rest of the band and began drinking heavily.[6]

Bare Trees was released in March 1972 and contained five Kirwan songs, including another instrumental, "Sunny Side of Heaven". The lyric for the album-closer, "Dust", was taken from a romantic poem by British war poet Rupert Brooke, although Brooke was not credited. "Danny's Chant" featured heavy use of the wah-wah guitar effect and was effectively an instrumental piece but for Kirwan's wordless scat vocals. "Bare Trees" and "Child of Mine", the latter touching upon the absence of Kirwan's father during his childhood, opened each side of the LP and showed funk and slight jazz leanings. An unissued Kirwan track, "Trinity", was played live for a period during 1971–1972 and the studio version was eventually released on the 1992 box set 25 Years – The Chain.

Firing from Fleetwood Mac

By the summer of 1972 Kirwan had been writing, recording, touring and performing continuously for nearly four years, since the age of 18, as a member of a major international band.[6] He had shouldered much of the songwriting responsibility during the band's recent troubled and uncertain period and through the changes in line-up and musical style. He had also found himself pushed reluctantly into the spotlight as lead guitarist to replace Peter Green.[6] The pressure eventually affected his health: he developed serious problems with alcoholism and there are stories of him not eating for several days at a time and subsisting mostly on beer.

The pressure and strain of life on the road, of constant travelling and performing, particularly affected Kirwan. As the band's 1972 tour progressed he became increasingly hostile, withdrawn and isolated and started drinking heavily.[6] Fleetwood said, "Danny had been a nervous and sensitive lad from the start. He was never really suited to the rigours of the business. Touring is hard and the routine wears us all down... Our manager kept us touring non-stop and we were being stretched to our limits. On that long tour in 1972 Danny became quite volatile and negative... and the pressure was obviously taking its toll. He simply withdrew into his own world."[6][12]

Kirwan became estranged from the other members of the band,[6][12] and things came to a head in August. Backstage before a concert on the US tour to promote Bare Trees, he argued with Welch over tuning their guitars and suddenly flew into a violent rage,[12] banging his head and fists against the wall. He smashed his Gibson Les Paul guitar, trashed the dressing room[12] and refused to go onstage. Kirwan watched the rest of the band struggle through the gig without him, heckling drunkenly from the mixing desk, and offered unwelcome criticism afterwards.[30][31]

Bob Welch remembered, "We had a university gig somewhere. Danny started to throw this major fit in the dressing room. He had a beautiful Les Paul guitar. First he started banging the wall with his fists, then he threw his guitar at the mirror, which shattered, raining glass everywhere. He was pissed out of his brain, which he was for most of the time. We couldn't reason with him."[32]

Fleetwood said, "We all felt a blow-up was brewing, but we didn't expect what happened. We were sitting backstage waiting to go on. Danny was being odd about tuning his guitar... He went off on a rant about Bob not being in tune [then] he got up suddenly... and smashed his head into the wall, splattering blood everywhere. I'd never seen him do anything that violent in all the years I'd known him. The rest of us were paralysed, in complete shock. He walked over to his precious Les Paul guitar and smashed it to bits. Then he set about demolishing everything in the dressing room as we all sat and watched. When there was nothing left to throw at the wall or overturn, he calmed down. Five minutes to showtime and there was blood everywhere. Danny said 'I'm not going on'. We were already late to the stage and we could hear the crowd chanting for us. We had to go onstage without him."[12][6]

Kirwan was sacked by Fleetwood, who had been the only member of the band still speaking to him. Fleetwood said, "The rest of us were hurt and insulted by what Danny had done... I was loathe to fire him because he played so well. Firing him would mean pulling out of two weeks of gigs and cancelling the tour... [but] there was no other option. Danny was a walking time-bomb, carrying all his emotional baggage around with him."[12][6]

Welch said that up until then the band had remained loyal to Kirwan, even when he became impossible to work with. "I would say, 'Mick, the guy doesn't show up to rehearsals, he's embarrassing, he's paranoid, we've spent five hours dealing with him', but Mick, John and Christine remained loyal to him because he was Peter's protégé."[27]

Fleetwood said later, "It was a torment for him, really, to be up there, and it reduced him to someone who you just looked at and thought 'My God'. It was more a thing of, although he was asked to leave, the way I was looking at it was, I hoped, it was almost putting him out of his agony."[21] He later commented, "I don't think he's ever forgiven me really."[33]

Kirwan said in 1993, "I couldn't handle it all mentally. I had to get out."[34]

Kirwan's reaction after being sacked was initially one of surprise, and it seemed he had little idea of how alienated from the other band members he had become.[21] Shortly afterwards he met up with his replacement Bob Weston. Weston described the meeting: "He was aware that I was taking over, and rather sarcastically wished me the best of luck – then paused and added, 'You're gonna need it.' I read between the lines that he was pretty angry with the band."[35]

In a 1993 interview with the British newspaper The Independent, however, Kirwan looked back at his time with the band and his departure from it and expressed no resentment. He said, "I was lucky to have played for the band at all. I just started off following them around, but I could play the guitar a bit and Mick felt sorry for me and put me in. I did it for about four years, to about 1972, but... I couldn't handle the lifestyle and the women and the travelling."[36]

Solo career and beyond

In early 1974 Kirwan and another recently fired member of Fleetwood Mac, guitarist Dave Walker, joined forces with keyboardist Paul Raymond, bassist Andy Silvester and drummer Mac Poole to form a short-lived band called Hungry Fighter.[37][38] This group played only one gig, at the University of Surrey in Guildford, England, which was not recorded. According to Walker, although Kirwan's playing was "superb", the band did not function properly because "perhaps we were not focused enough musically, and in addition, Danny Kirwan's problems were just starting and this made communication extremely difficult."[38]

Guided by ex-Fleetwood Mac manager Clifford Davis, Kirwan later recorded three solo albums for DJM Records. These albums showed a gentler side of his music, as opposed to the blues guitar dynamics of his Fleetwood Mac years. The first of these, Second Chapter (1975), exhibited various musical influences, including a style close to that of Paul McCartney later in his Beatles career.[39] Many of the songs were very simple musically, with little more than infectious melody and basic lyrics to sustain them. Lyrical themes rarely ventured beyond love.

Midnight in San Juan (1976) featured a reggae-inspired cover of The Beatles' "Let It Be", which was released as a single in the USA. Otherwise Kirwan tended towards simpler tunes and dispensed with the heavy production which had dominated his previous album. The lyrics were still mostly about love but were less cheerful than before, with growing themes of loneliness and isolation, such as on the closing track, "Castaway". One song, "Look Around You", was written by fellow Mac refugee Dave Walker, with whom Kirwan had worked in Hungry Fighter a couple of years previously.

Kirwan's last album, Hello There Big Boy!, featured guitar contributions from his Fleetwood Mac replacement Bob Weston. Kirwan was not well at this time and it is not clear how much, if any, guitar work he contributed to the recording, although he did sing on all the tracks. Fewer of the songs were self-penned and there was one song, "Only You", which was retrieved from his Fleetwood Mac days. There were also backing vocalists for the first time, and the musical style was much less distinct. A press release stated that producer Clifford Davis had added contributions from 87 musicians to the final recording.[40] Davis later described the album as "so bad", adding, "[Kirwan] had to finish it for contractual reasons, but I had to put down the acoustic guitar parts and the vocals. I even picked the songs."[30]

None of Kirwan's solo releases was commercially successful, which could be attributed to his reluctance to perform live. Kirwan did not play any live gigs after a few shows with Tramp and the single performance with Hungry Fighter, all in 1974. This left all three of his solo albums unsupported by any form of extra exposure or active promotion, apart from an irregular string of equally unsuccessful singles. None of his singles was released in continental Europe, where he might have enjoyed some success given Peter Green's resurgence there, particularly in Germany.

Kirwan married Clare Stock in 1971 but was divorced a few years later.[40] They had one son, Dominic Daniel, born in 1971.[41]

Mental health

Kirwan's mental state appears to have been fragile before he became involved with Fleetwood Mac. The band's manager, Clifford Davis, said that Kirwan's mother had split from his father "and Danny was always trying to find him. He had a lot of problems with self-confidence and security.... Hurled into the Fleetwood Mac circus in his teens, he found the fame hard to cope with."[42] Christine McVie said after his death, "Danny was a troubled man and a difficult person to get to know. He was a loner."[43] Kirwan was described by those who knew him as shy, nervous, withdrawn and difficult to work with. Bob Welch said the other band members had described him as "a little strange".[44] Fleetwood said Kirwan "carried all his emotional baggage around with him. It was a major event to ask him for a cigarette."[6] In sleeve notes to the reissued Then Play On, he described Kirwan as "a confused young man." Welch said Kirwan was "one of the strangest people I've ever met, very nervous, hard to establish a rapport with.... [but] he was also a very intuitive musician.... He played with surprising maturity and soulfulness. There was something idealistic and pure about him."[45]

In the late 1970s Kirwan's mental health deteriorated, and since then he has played no further part in the music industry. During the 1980s and 1990s he endured a period of homelessness in London.[46] In 1989 Bob Brunning, wanting to interview Kirwan for a book he was writing, tracked him down to the St Mungo Community Hostel for the Homeless in Soho. Brunning says Kirwan was "still slim, but puffy-cheeked and highly agitated. He couldn't talk coherently, just said, 'Can't help you Bob. Too much stress.'"[47] In 1993 Kirwan, then aged 42, was located and interviewed by the British newspaper The Independent. He was staying at a St Mungo's hostel for the homeless in London, where he had been for the past four years, and was living on social security and royalties from the band's early days. He told the Independent, "I've been through a bit of a rough patch, but I'm not too bad. I get by. I suppose I am homeless, but then I've never really had a home since our early days on tour."[48][49] In March 1996 Kirwan was reported to be living as a down-and-out in Covent Garden, London, sleeping on park benches, and was a semi-permanent resident of a hostel for the homeless.[48] In July 2000, just after his 50th birthday, he was reported to be happily settled in a care home, where he had been for some time. He was said to be looking "fitter, stronger and more together". His ex-wife Clare had been keeping in touch with him. Kirwan was said to keep a guitar in his room, which he played often for his own pleasure. He remained a private person who kept to himself.[48]

Peter Green's biographer Martin Celmins met Kirwan in London and managed a brief interview, which was published in The Guitar Magazine [UK] in July 1997. Celmins asked Kirwan how he had come to play the blues. Kirwan said "I was around and gathered it all up and got involved. I didn't think 'I want to be a musician'. It just kind of happened... I got into the blues and it got into my system." He said his favourite bluesmen were Albert King and Otis Rush. Rush "had this nice sting in his playing that was his... that was his stamp." Celmins asked about big-band music and Django Reinhardt. "Those were the kind of records I'd buy. I worked out "Jigsaw Puzzle Blues" from that stuff and then played the signals to the rest of the band. John McVie knew every signal you could give out – signals to say 'You do this' and 'You do that' and they'd do it and it would all come together. That band was so clever – they knew all the signals and could do it." Celmins asked how he had joined the band. "Mick Fleetwood asked me... I didn't know what to think once I'd joined because... then I was on stage and there were television cameras and I got a bit paranoid." Kirwan said, "I always liked Mick Fleetwood – he was like family. I still think of them as friends. John McVie is the cleverest person. A nice bloke and highly intelligent. He was my best friend in the band at the time... Jeremy Spencer was a bit sarcastic. And although I used to get on with John and Mick, it got very cliquey... So I wasn't actually a part of them really. I only got mixed up with them... [Peter and I] played some good stuff together, we played well together, but we didn't get on. I was a bit temperamental, you see."[16]

In a 2009 BBC documentary about Peter Green, and also in Bob Brunning's book 'Fleetwood Mac: The First 30 Years' [1998],[50] the band's manager, Clifford Davis, blamed Kirwan's mental deterioration on the same incident in March 1970 that is alleged to have damaged Green's mental stability: a reaction to LSD taken at a hippie commune in Munich. Davis said, "Peter Green and Danny Kirwan both went together to that house in Munich, both of them took acid as I understand it, [and] both of them, as of that day, became seriously mentally ill."[51]

Other sources, however, say that Kirwan was not present at the commune in Munich. Fleetwood Mac roadie Dinky Dawson remembers that only two of the Fleetwood Mac contingent went to the party: Green and another roadie, Dennis Keane. Dawson states that Kirwan did not go to the commune, and that when Keane returned to the band's hotel and told them that Green would not leave the commune, neither Kirwan nor Davis went to fetch him, leaving the task to Keane, Dawson and Mick Fleetwood.[52] Keane agrees with Dawson's account, except for the details that he phoned Davis from the commune and did not physically return to the hotel to fetch help; and that Davis accompanied Dawson and Fleetwood to fetch Green.[53] Green said of the incident, "To my knowledge, only Dennis and myself out of the English lot went there."[53] Jeremy Spencer has stated that he was also present at the commune and has implied that he arrived later with Fleetwood.[54] Neither Keane, Dawson, Green nor Spencer mention Kirwan being present at the commune.

Kirwan appears, however, to have taken LSD before the Munich commune incident. Fleetwood states that all the members of the band had previously taken LSD together as "a bonding experience".[6] The first time was in early December 1968, when they arrived in the US at the start of their second tour.[6] They opened for the Grateful Dead at the Fillmore East[6] and were offered what they understood to be "the best, most pure LSD available".[6] He said, "We all wanted to try it... We all had a go."[6] They took the LSD together in a hotel room in New York, "sitting in a circle on the floor, holding hands."[12] Fleetwood said, "LSD was a bonding experience that we did together on other occasions... [it] brought our collective consciousness together."[12] He added, "It never became a regular thing, [but] LSD played its role."[12] Fleetwood said that Kirwan had also taken mescaline. When the band arrived in San Francisco in February 1971 at the start of a US tour, Kirwan and Spencer took the drug "and it really did a number on them, Jeremy in particular. The effects seemed to last far longer than they should have."[12] The following day Spencer walked out of the band.[6]

Later developments

Kirwan was inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, in 1998 for his work as part of Fleetwood Mac, although he did not travel to the induction ceremony.[55]

His three solo albums were given a belated CD release in February 2006, but only in Japan. A limited edition of 2,500 copies of "Second Chapter" was issued by Repertoire Records in early 2008. The rights and royalties situation regarding these releases is currently such that it is not commonly known if Kirwan's estate will receive any income from them. Prior to this, only Second Chapter had been available on CD, for a brief period in Germany in 1993. The rights are now owned by Clifford Davis.

During the mid-2000s, there were rumours of a reunion of the early line-up of Fleetwood Mac, involving Green and Spencer. The two guitarists apparently remained unconvinced about a reunion[20] and Kirwan made no comment on the subject. In April 2006, during a question-and-answer session on the Penguin Fleetwood Mac fan website, bass player John McVie said of the reunion idea, "If we could get Peter and Jeremy to do it, I'd probably, maybe, do it. I know Mick would do it in a flash. Unfortunately, I don't think there's much chance of Danny doing it. Bless his heart."[56]

Death

Kirwan died in London on 8 June 2018.[57] In a statement posted on Facebook, Mick Fleetwood said: "Danny’s true legacy will forever live on in the music he wrote and played so beautifully as a part of the foundation of Fleetwood Mac that has now endured for over fifty years. Thank you, Danny Kirwan. You will forever be missed."[58] An obituary in The New York Times noted that Kirwan's former wife, Clare Morris, said he had died in his sleep after contracting pneumonia earlier in the year and never fully recovering from it.[41] The British music magazine Mojo, in a two-page tribute to Kirwan's life and music, said Jeremy Spencer had met Kirwan in London in 2002 with his ex-wife Clare and their son Dominic. Kirwan was living in a care home in south London, "where he was well looked after and visited by family and friends until the end".[43]

Mojo quoted Christine McVie as saying: "Danny Kirwan was the white English blues guy. Nobody else could play like him. He was a one-off... Danny and Peter gelled so well together. Danny had a very precise, piercing vibrato – a unique sound... He was a perfectionist... Listen to "Woman of 1000 Years", "Sands of Time", "Tell Me All the Things You Do" – they're killer songs. He was a fantastic musician and a fantastic writer." Jeremy Spencer said, "Danny brought inventiveness and melody to the band... I was timid about stepping out with new ideas, but Danny was brimming with them."[43] Bob Welch said in 1999 that Kirwan had been a talented and gifted musician, "almost equal to Pete Green in his beautiful guitar playing and faultless string bends."[24] Mick Fleetwood said in 1990: "Danny was an exceptional guitar player who inspired Peter into writing the most moving and powerful songs of his life."[6]

Equipment

- Watkins Rapier 33, 1960s British-made Fender Stratocaster-style guitar, with a chambered body. Kirwan's was red, and he used it when in Boilerhouse, and during early Fleetwood Mac performances (e.g. Hyde Park, London, free concert 1968).

- Fender Telecaster Standard Blonde. Used on "Like Crying".

- 1956 Gibson Les Paul Standard, Goldtop, P-90 pickups, no pickguard, later refinished to red.

- 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, Cherry Sunburst, no pickguard.

- 1959 Gibson Les Paul Standard, Tobacco Sunburst, no pickguard.

- 1957 Gibson Les Paul Custom, 3 pickup Black Beauty, no pickguard.

- Orange Matamp 100W valve (vacuum tube) amplifier, usually used with two 4 x 12 Orange speaker cabinets (used by the whole band for a period) and separate Orange (valve) spring reverb unit.

- Fender Dual Showman amplifier

Discography

Solo albums

- Second Chapter (DJM 1975)

- Midnight in San Juan (DJM 1976)

- Danny Kirwan (DJM 1977 – US release of Midnight in San Juan)

- Hello There Big Boy! (DJM 1979)

- Ram Jam City (Mooncrest 2000 – recorded in the mid-1970s as demo tracks for the Second Chapter album)

References

- ↑ "Birth name of Danny Kirwan". GRO Birth Indexes. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- ↑ "Marriage of mother of Danny Kirwan". GRO Civil Registration Marriage Index. Retrieved 25 August 2018.

- 1 2 3 Sweeting, Adam (2018-06-14). "Danny Kirwan obituary". the Guardian. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- 1 2 3 Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press

- ↑ Rawlings, Terry (2002). Then, now and rare British Beat 1960-1969. Omnibus Press. p. 77. ISBN 0-7119-9094-8.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Mick Fleetwood with Stephen Davis (1990). My Life and Adventures with Fleetwood Mac. Sidgewick & Jackson, London.

- ↑ Celmins, Martin. Peter Green: Founder of Fleetwood Mac. Castle. p. 67. ISBN 1-898141-13-4.

- ↑ "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Jeremy Spencer, June 1999". The Penguin. June 1999. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 The Vaudeville Years (CD booklet notes). Fleetwood Mac. Receiver Records. 1998.

- 1 2 Vernon, Mike (1999). The Complete Blue Horizon Sessions (CD box set booklet). Fleetwood Mac. Sire Records.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press p18

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Mick Fleetwood (30 October 2014). Play On: Now, Then and Fleetwood Mac. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4447-5326-4.

- 1 2 3 Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press p19

- ↑ Danny Kirwin obituary//www.rhino.com

- 1 2 3 4 5 Show-Biz Blues (CD booklet notes). Fleetwood Mac. Receiver Records. 2001.

- 1 2 The Guitar Magazine, Bath, UK, vol 7, no.9, July 1997: "A Rare Encounter with Danny Kirwan": Martin Celmins

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p21

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. pp29-30

- ↑ Christine Perfect (LP album sleeve notes). Christine Perfect. Blue Horizon. 1970.

- 1 2 3 4 Wasserzieher, Bill (October 2006). "The Return of Jeremy Spencer". Blues Revue. Archived from the original on 20 February 2008. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- 1 2 3 4 "Interview with Mick Fleetwood, John McVie, and Christine McVie". Insight. November 1976. BBC. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ Mick Fleetwood (30 October 2014). Play On: Now, Then and Fleetwood Mac. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4447-5326-4.

- ↑ Mick Fleetwood (30 October 2014). Play On: Now, Then and Fleetwood Mac. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1-4447-5326-4.

- 1 2 "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Bob Welch, November 8–21, 1999". The Penguin. 21 November 1999. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Bob Welch, August 4–17, 2003". The Penguin. 2003-04-17. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p39

- 1 2 Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p38

- ↑ Future Games (CD booklet notes). Fleetwood Mac. Reprise. 1971.

- ↑ Mojo magazine, September 2018: "A Loner and a One-Off: Danny Kirwan 1950-2018" - Mark Blake.

- 1 2 Brunning, Bob (1990). Fleetwood Mac: Behind the Masks. London: New English Library. ISBN 0-450-53116-3. OCLC 22242160.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p39-40

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. pp39-40

- ↑ "Rock Family Trees: The Fleetwood Mac Story", dir. Francis Hanly, 1995.

- ↑ "He went his own way to oblivion: Fleetwood Mac's former guitarist is". The Independent. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ↑ "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Bob Weston, December 6–19, 1999". The Penguin. 19 December 1999. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "He went his own way to oblivion: Fleetwood Mac's former guitarist is". The Independent. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

- ↑ "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Dave Walker, October 12–25, 2000, Page 1". The Penguin. 12 October 2000. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- 1 2 "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: Dave Walker, October 12–25, 2000, Page 2". The Penguin. 12 October 2000. Retrieved 2010-08-10.

- ↑ Viglione, Joe. "Second Chapter review". Allmusic. Rovi Corporation. Retrieved 2011-07-27.

- 1 2 Hogan, Richard (1979). "Press release for Hello There Big Boy!". DJM Records.

- 1 2 "Danny Kirwan, Guitarist in Fleetwood Mac's Early Years, Dies at 68". The New York Times. 10 June 2018. Retrieved 13 June 2018.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. pp19&40

- 1 2 3 Mojo magazine, London, September 2018: "A Loner and a One-Off: Danny Kirwan 1950-2018" Mark Blake.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p39

- ↑ ""The Penguin Biographies: Danny Kirwan"". Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ Jacey Fortin. "Danny Kirwan, Guitarist During Fleetwood Mac's Early Years, Dies at 68". The New York Times.

He surfaced briefly in 1993 when, in an interview with The Independent, Mr. Kirwan said he had been homeless.

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. p41

- 1 2 3 ""The Penguin Biographies: Danny Kirwan"". Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- ↑ https://www.independent.co.uk/news/he-went-his-own-way-to-oblivion-fleetwood-macs-former-guitarist-is-found-a-little-the-worse-for-wear-1511056.html

- ↑ Brunning, B (1998): Fleetwood Mac – The First 30 Years. London: Omnibus Press. pp28&40

- ↑ Clifford Davis, "Peter Green: Man of the World", BBC TV, 2009.

- ↑ Dawson, Dinky & Alan, Carter, "Life on the Road", Billboard, 1998, pp.131–132.

- 1 2 Celmins, Martin. Peter Green: Founder of Fleetwood Mac. Castle. ISBN 1-898141-13-4. pp110-111

- ↑ Jeremy Spencer interviewed by Steve Clark, NME magazine, 5 October 1974.

- ↑ "Fleetwood Mac". Rock & Roll Hall of Fame. Retrieved 2018-02-10.

- ↑ "The Penguin Q&A Sessions: John McVie Q&A Session, Part 2". The Penguin. January 2006. Retrieved 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Fleetwood Mac guitarist Danny Kirwan dies, aged 68". Louder Sound. 9 June 2018.

- ↑ "Fleetwood Mac's 'Forgotten Hero,' Guitarist Danny Kirwan, Has Died". NPR.org. Retrieved 2018-06-14.

Further reading

- Lewry, Peter (1998). Fleetwood Mac: The Complete Recording Sessions 1967–1997. London: Blandford. ISBN 0-7137-2724-1. OCLC 40608634.

- "The Penguin Biographies: Danny Kirwan". The Penguin. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- Freedland, Jan; Fitzgerald, John (1 October 2006). "Danny Kirwan Biography". The Fleetwood Mac Legacy. Archived from the original on 22 April 2008. Retrieved 20 May 2008.

- Fleetwood, Mick; Davis, Stephen (1992). My 25 Years in Fleetwood Mac. New York: Hyperion. ISBN 1-56282-936-X. OCLC 25788644.

External links

- Danny Kirwan discography at MusicBrainz