Crest-tailed mulgara

| Crest-tailed mulgara | |

|---|---|

| |

| Crest-tailed mulgara, Simpson Desert | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Infraclass: | Marsupialia |

| Order: | Dasyuromorphia |

| Family: | Dasyuridae |

| Genus: | Dasycercus |

| Species: | D. cristicauda |

| Binomial name | |

| Dasycercus cristicauda (Krefft, 1867) | |

| |

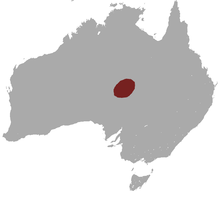

| Crest-tailed mulgara range | |

The crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda), is a small to medium sized Australian carnivorous marsupial and a member of the family Dasyuridae (meaning "hairy tail")[1] which includes quolls, dunnarts, the numbat, Tasmanian devil and extinct thylacine. The crest-tailed mulgara is among a group of native predatory mammals or mesopredators endemic to arid Australia.[2]

Description

The crest-tailed mulgara is a small to medium-sized mammal with sandy coloured fur on the upper parts leading to a darker grey on the under parts and inner limbs.[3] The species is strongly sexually dimorphic with adult males weighing 100 g (3.5 oz) or more and females under 80 g (<2.8 oz).[2] Mean weight range is between 70-170 g (2.1-6 oz), head-body length of 125–220 mm (4.9–8.7 in) and tail length is between 75–125 mm (3.0–4.9 in).[3] Identification between the two species within the Dasycercus genus has proven difficult with the crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda) often confused with the brush-tailed mulgara or ampurta (D. blythi). Tail morphology is a primary identifying feature between the two species.[2] The crest-tailed mulgara has a crest of fine black hairs along the dorsal edge of the tail creating a fin-like crest and hair length tapering towards the tip. In contrast the brush-tailed mulgara tail hair is not crested, black hair starts half way along the upper surface of the tail and dorsal hair length remains consistent.[3] Nipple count also differs between the two species and is another distinguishing feature. The female crest-tailed mulgara has eight nipples compared to the brush-tailed mulgara who only has six.[2][3][4]

Taxonomy

There has been taxonomic confusion within the genus Dasycercus described by Peters in 1875.[3] Four named forms of carnivorous marsupials have been assigned to this genus.[3] Kreft,1867, first described Chaetocercus cristicauda in 1877.[3] A second form, Phascogale blythi was described by Waite, 1904, followed by a third form, Phascogale hillieri described by Thomas,1905.[3] Decades on, William Ride’s 'A Guide to the Native Mammals of Australia' published in 1970 referred only to a single species, Dasycercus cristicauda, and in 1988 Mahoney and Ride placed all three species in the synonomy of D. cristicauda.[3] A fourth species, Dasyuroides byrnei, described by Spencer, 1896, was included by Mahoney and Ride however a lack of consensus resulted in its exclusion to the Dasycercus genus.[3] Based on tail characteristics, dentition and number of nipples, Woolley resolved the taxonomic and nomenclatural issues in 2005 and the species was re-split to two genetically distinct forms, D. cristicauda and D. blythi with D. hilleri remaining in the synonomy of D. cristicauda.[3] Evidence of two clades was supported using mitochondrial gene sequencing conducted by Adams and others in 2000.[3] Currently two separate species are recognised; the crest-tailed mulgara (D. cristicauda) and brush-tailed mulgara or ampurta (D. blythi). For the crest-tailed mulgara there are no subspecies.[5]

Distribution

The crest-tailed mulgara inhabits areas of arid Australia. It has been recorded in the southern Simpson Desert near the tri-state border and in the Tirari and Strzelecki Deserts of South Australia and the western Lake Eyre region.[6] Historically the species’ geographic range was much larger incorporating areas from Ooldea on the eastern edge of the Nullarbor Plain and the Musgrave Ranges in South Australia, Sandringham Station in Queensland (last record in 1968) and from the Canning Stock Route and near Rawlinna on the Nullarbor Plain in Western Australia.[6] Owl pellet examinations showed presence of crest-tailed mulgara near the southern and south-eastern margins of the Strzelecki dunefield/sandplain, in the Flinders Ranges and at Mutawintji National Park in far-western New South Wales.[7] Due to the levels of taxonomic uncertainty, misidentification may have led to an overestimated distribution especially when based on older records. This has created difficulties in assessing and interpreting temporal changes within its historic distribution.[5]

Ecology and Habitat

Habitat

The crest-tailed mulgara inhabits crests and slopes of sand ridges of inland Australia.[2][8] During the day it shelters in burrows which are located at the base of sandhill canegrass (Zygochloa paradoxa) clumps [2] or bushes [5] and around the edges of salt lakes.[3] Burrow characteristics are shown to have flat bottomed entrances with an arch-shaped opening with systems recorded to have between two and nine entrances [9] and can be confused with those of spinifex hopping mice.[8] Burrow site suitability, rainfall, food resources and the fire age of the vegetation community may be a factor influencing their distribution.[2]

Diet

A nocturnal hunting specialist, the crest-tail mulgara’s diet is comprised mostly of insects, arachnids and rodents but also includes reptiles, centipedes and small marsupials.[10] Seasonal dietary shifts have been observed with a higher percentage of rodents and insects consumed in winter and spring compared to autumn where diet consists mainly of insects.[10] Prey size preference is recorded to be greater than 7.5 mm (0.3 in) and crest-tailed mulgaras are the only dasyurid known to regularly include hard beetles in their diet.[11] This dietary flexibility enables this species to persist and may assist individuals to occupy stable home ranges.[10]

Breeding and reproduction

The crest-tailed mulgara reaches sexual maturity in the first year and reproduction occurs between winter and early spring.[5] Gestation period is between 43–48 days and like many dasyurids, spontaneous torpor has been observed in laboratory studies.[12] Influenced by reproductive status and sex, females entered torpor frequently during pregnancy and after the lactation period and males were observed to enter torpor throughout the reproductive season and after mating.[12]

Conservation Status

The following are the federal, state and international listings for the crest-tailed mulgara.[6] The mulgara was presumed extirpated in New South Wales for more than a century, but was re-discovered in 2017 in Sturt National Park north-west of Tibooburra.[13]

Federal Listing Status

Under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (the EPBC Act): Listed as Vulnerable.

Non-statutory Listing Status

IUCN: Listed as Near Threatened (Global Status: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species).

WA: Listed as P4 (Priority Flora and Priority Fauna List (Western Australia)).

NGO: Listed as Near Threatened (The Action Plan for Australian Mammals 2012).

State Listing Status

NSW: Listed as Extinct (Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016), April 2018.

NT: Listed as Vulnerable (Territory Parks and Wildlife Conservation Act 2000), 2012.

QLD: Listed as Vulnerable (Nature Conservation Act 1992), September 2017.

SA: Listed as Endangered (National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972), June 2011.

Threats

The crest-tailed mulgara is sensitive to predation by the European red fox and feral cat,[2] changes to fire regimes together with environmental degradation and habitat homogenization attributed to grazing from livestock and introduced European rabbits.[7][14] During post-release of rabbit hemorrhagic disease virus (RHDV), the crest-tailed mulgara underwent a 70-fold increase in its extent of occurrence and a 20-fold increase in its area of occupancy.[15]

_closeup.jpg)

References

- ↑ "A mammalian lexicon". Biology of Mammals. 27 May 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Pavey, C. R., Nano, C. E. M., Cooper, S. J. B., Cole, J. R., & McDonald, P. J. (2012). Habitat use, population dynamics and species identification of mulgara, Dasycercus blythi and D. cristicauda, in a zone of sympatry in central Australia. Australian Journal of Zoology, 59(3), 156-169. doi:10.1071/ZO11052

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Woolley, P.A. (2005). The species of Dasycercus Peters, 1875 (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae). Memoirs of Museum Victoria, 62(2), 213–221.

- ↑ Menkorst, P. & Knight, F. (2011). A field guide to the mammals of Australia. Melbourne, Victoria, Australia: Oxford. p. 52-53. ISBN 9780195573954.

- 1 2 3 4 Woinarski, J. & Burbidge, A.A. 2016. Dasycercus cristicauda. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2016: e.T6266A21945813. http://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-1.RLTS.T6266A21945813.en. Downloaded on 05 June 2018

- 1 2 3 "Species Profile and Threats Database". Australian Government Department of Environment and Energy. 6 June 2018.

- 1 2 Letnic, M., Feit, A., Mills, C., & Feit, B. (2016). The crest-tailed mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda) in the south-eastern Strzelecki Desert. Australian Mammalogy, 38(2), 241-245. doi:10.1071/AM15027

- 1 2 Thompson, G. & Thompson, S. (2014). Detecting burrows and trapping for mulgaras (Dasycercus cristicauda and D. blythi) can be difficult. Australian Mammalogy, 36(1), 116-120. doi:10.1071/AM13031

- ↑ Thompson, G. G. & Thompson, S. A. (2007). Shape and spatial distribution of Mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda) burrows, with comments on their presence in a burnt habitat and a translocation protocol. Journal of the Royal Society of Western Australia,90, 195-202.

- 1 2 3 Chen, X., Dickman, C., & Thompson, M. (1998). Diet of the mulgara, Dasycercus cristicauda (Marsupialia: Dasyuridae), in the Simpson Desert, central Australia. Wildlife Research, 25(3), 233-242. doi:10.1071/WR97087abs

- ↑ Fisher, D. O. & Dickman, C. R. (1993). Diets of insectivorous marsupials in arid Australia: selection for prey type, size or hardness? Journal of Arid Environments, 25, 397–410.

- 1 2 Geiser, F. & Masters, P. (1994). Torpor in relation to reproduction in the mulgara, Dasycercus cristicauda (Dasyuridae: Marsupialia). Journal of Thermal Biology, 19(1), 33-40.

- ↑ z3517017 (2017-12-15). "Mammal long thought extinct in NSW resurfaces in state's west". UNSW Newsroom. Retrieved 2017-12-18.

- ↑ "Threatened Species of the Northern Territory" (PDF). Crest-tailed Mulgara (Dasycercus cristicauda).

- ↑ Pedler, R. D., Brandle, R., Read, J. L., Southgate, R., Bird, P., & Moseby, K. E. (2016). Rabbit biocontrol and landscape‐scale recovery of threatened desert mammals. Conservation Biology, 30(4), 774-782. doi:10.1111/cobi.12684