Corsican nationalism

Corsican nationalism is a nationalist movement in Corsica, France, active since the 1960s, that advocates more autonomy for the island, if not outright independence.

Political support

The main separatist party (Corsica Libera) achieved 9.85% of votes in the French regional elections, 2010;[1] however, only 19% and 42% of those who voted respectively for Simeoni's autonomist list Femu a Corsica and Talamoni's separatist Corsica Libera were, according to polling, in favour of independence.[2][3] By 2012, polls showed support for independence at 10-15%,[3] while support for increased devolution within France was as high as 51% (of which two thirds would prefer "slightly more" rather than "much more" autonomy).[4] Among the general French population, 30% of respondents expressed a favourable view on Corsican independence.[5] In what was viewed as a "setback" for Nicolas Sarkozy's decentralisation program, the government's proposal for increased autonomy for Corsica was turned down in a referendum in 2003 by a result of 51% negative and 49% affirmative votes expressed by the local electorate.

In 2015, Gilles Simeoni's pro-autonomy coalition Pè a Corsica won for the first time ever in the French regional elections, getting 35.34% of the vote and 24 out of 51 seats in the Corsican Assembly.[6][7]

History

In 1923 the party Partitu Corsu d'Azione was created by Petru Rocca, an Italian irredentist who initially promoted the union of Corsica to the Kingdom of Italy but after World War II changed to promote Corsican autonomism with the Partitu Corsu Autonomista. Rocca in 1953 demanded from France the acceptance of the Corsican people and language and the creation of the University of Corte.

Corsica in the 1960s

The end of the 1950s saw the high point of Corsica's population and economy. Since the end of the 19th Century, Corsica had continued to decrease in population, culminating in a precarious economic situation and a huge delay in the development of industry and infrastructure.

Corsican society was then further affected by two events:

- The first was the collapse of the French colonial empire. The Colonial Army and colonial enterprises were the principal form of employment for Corsicans. In 1920, Corsicans made up 20% of colonial administration, despite only making up 1% of Metropolitan France's population. The end of colonialism deprived young Corsicans of the opportunities of their elders and forced many to return to the island. This situation resulted in the emergence of a regionalist movement with the objective of increasing the number of opportunities for the islanders. During the uprisings in Algeria in 1958 and 1961, Corsica was the only French départment that joined the insurgent colonists.

- The second shock was the arrival of people returning from the former African colonies, to whom the state controversially granted land in the eastern plain. At the beginning of the 1960s, before the arrival of returnees from Algeria, they represented around 10% of the island's population.

The first regionalist movements

Many Corsicans began to become aware of the demographic decline and economic collapse of the island. The first movement appeared as the Corsican Regional Front, in which a majority split gave Corsican Regionalist Action, and demanded that the French state take into account the island's economic difficulties and distinct cultural characteristics, notably linguistic, greatly endangered by the demographic decline and economic difficulty. These movements have caused a major revival of the Corsican language, and an increase in work to protect and promote Corsican cultural traditions.

But these movements felt that their demands were being ignored and saw the state's treatment of the returnees as a sign of contempt. They argued against the idea that Corsica was made up of "virgin land" where there is no need to consult the local population on repatriation, and criticised the financial support and aid received by the new arrivals through the Society for Agricultural Development of Corsica (SOMIVAC), which had never been offered to the Corsicans.

The Aléria incident and the birth of the FLNC

In a situation that many considered dire, the group Corsican Regionalist Action (ARC) decided to choose more radical methods of action.

On 21 August 1975, twenty members of the ARC, led by the group's leader Edmond Simeoni, occupied the Depeille cave, in the eastern plains near Aléria. Equipped with rifles and machine guns, they wanted to bring to public attention the economic situation of the island, particularly that regarding agriculture. They denounced the takeover of lands in the east of the island by "pieds-noirs" and their families. The French Interior Minister at the time, Michel Poniatowski, sent 2,000 CRS and gendarmes backed with light armoured vehicles, and ordered an attack on the 22nd at 4pm. Two gendarmes were killed during the confrontation. A week later the cabinet ordered the dissolution of the ARC. The tension rose rapidly in Bastia and scuffles broke out in the late afternoon, which turned to riots by nightfall that included armed confrontation. One member of the ARC was killed and many were wounded.

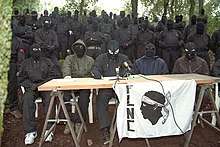

On 4 May 1976, some months after the events in Aléria, nationalist militants founded the National Liberation Front of Corsica (FLNC), a joining of Fronte Paesanu di Liberazone di a Corsica (FPCL), responsible for the bombing of a polluting Italian boat, and Ghjustizia Paolina, reputed to be the armed wing of the ARC. The founding of this new group was marked by a series of bombings in Corsica and in mainland France. A press conference was held in Casabianca, the location of the signing of the Corsican Constitution and where Pasquale Paoli declared Corsican independence in 1755. Although claiming to be influenced by Marxist ideology, most separatist leaders have been from the nationalist right or "apolitical" backgrounds.

Themes of Corsican nationalism

- Political sovereignty of Corsica: independence from France or increased autonomy in France. Separation from France is partially based on cultural and ethnic differences between the island and the mainland. The imposition of a revolutionary tax was practised in the 1980s, and continues to be imposed by the FLNC, or people claming to be associated with it. The bombings against state buildings have been constant: attacks against prefectures, prisons, tax offices, military camps, the assassination of Claude Érignac, etc. But greater in number are the bombings of second homes belonging to foreigners and mainlanders.

- The promotion of the Corsican language, and its compulsory teaching in schools.

- The limiting of tourist infrastructure and policies promoting tourism, and in its place another way to boost economic development.

- Compliance with building permits.

- Compliance with coastal law.

- Recognition of political prisoner status for imprisoned members of the FLNC, including those who have been convicted for common-law violations.

Corsican nationalism and international investment

The Corsican coast is less developed than mainland France's Mediterranean coast, due in part to bombings attributed to the nationalist movement against a number of second homes belonging to non-natives.[8][9]

U Rinnovu, a Corsican nationalist movement commonly referred to as being close to a splinter group of the FLNC known as "of 22nd October", describes the construction of second homes for the benefit of non-residents as "heresy" and "against economic sense".[10] The slogan Vergogna à tè chì vendi a tò terra ("Shame on you who sell your land") is also the title of a song and nationalist anthem.

At the Matignon process under the Jospin government, Article 12 of the Matignon Accords provided for an adjustment of the coastal law making it easier to issue building permits on the Corsican coast. On the day of the discussion of this article in the Corsican Assembly, activists from the organisation A Manca Naziunale surrounded the villa of André Tarallo of the French petroleum company Elf Aquitane in Piantaredda, against the granting of contested building permits.[11] The article was subsequently rejected.

Notable people and parties

- Parties

- Pè a Corsica (political party)

- FLNC (militant group)

- Party of the Corsican Nation (political party)

- A Cuncolta Naziunalista (militant group, defunct)

- People

- Leo Battesti (b. 1953)

- Yvan Colonna (b. 1960)

- Gilbert Casanova, founder of the Movement for Self-determination (MPA) and ex-president of the Corse-du-Sud Chamber of Commerce, imprisoned in 2008 for drug trafficking.[12][13]

- Gilles Simeoni, (b. 1967)

- Napoleon, French military and political leader was a passionate Corsican nationalist in his younger years.[14]

Bibliography

- Jean-Louis Andreani, Comprendre la Corse, Gallimard, 2005

- Daniel Arnaud, La Corse et l'idée républicaine, L'Harmattan, 2006

- Emmanuel Barnabeu Casanova, Le nationalisme corse : genèse, succès et échec, L'Harmattan

- Ange-Laurent Bindi, Autonomisme. Luttes d'émancipation en Corse et ailleurs 1984-1989, L'Harmattan

- Gabriel Xavier Culioli, Le complexe corse, Gallimard

- Marc de Cursay, "Corse : la fin des mythes", L'Harmattan

- Pascal Irastorza, Le guêpier corse, Fayard, 1999

- Marianne Lefèvre, Géopolitique de la Corse. Le modèle républicain en question, L'Harmattan

- Jean-Michel Rossi / François Santoni, Pour solde de tout compte, les nationalistes corses parlent, Denoël

- Pierre Poggioli, Journal de bord d'un nationaliste corse, Éditions de l'Aube, 1996

- Pierre Poggioli, Corse : chroniques d'une île déchirée 1996-1999, L'Harmattan, 1999

- Pierre Poggioli, Derrière les cagoules : le FLNC des années 80, DCL Editions

- Edmond Simeoni, Corse, la volonté d'être. Vingt ans après Aléria, Albiana

- Bonardi Fabrice, Corse, la croisée des chemins, L'Harmattan, 1989

References

- ↑ Résultats des élections régionales 2010, Ministère de l'Intérieur

- ↑ "Les Corses plus indépendantistes aujourd'hui qu'il y a 40 ans", Corse-Matin, 9 August 2012 (in French)

- 1 2 Jérôme Fourquet, François Kraus, Alexandre Bourgine - Les Corses et leur perception de la situation sur l’île: Résultats détaillés

- ↑ Jérôme Fourque - Enquête sur la situation en Corse: Résultats détaillés

- ↑ Les Français et l’indépendance de la Corse - Résultats détaillés, IFOP, October 2012 (in French)

- ↑ Territoriales : les résultats définitifs du second tour - France 3 Corse ViaStella (in French)

- ↑ Elections régionales et des assemblées de Corse, Guyane et Martinique 2015, Interior Ministry of France (in French)

- ↑ "Recrudescence d'attentats contre des villas en Corse", Le Figaro, 24 April 2006

- ↑ Marc Pivois, Les assurances ne veulent prendre aucun risque en Corse, Libération, 7 October 2004

- ↑ U Rinnovu

- ↑ Communiqué de Manca Naziunale Archived 20 May 2009 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Xavier Monnier, Parties de belote aux Baumettes Archived 14 September 2008 at Archive.is, Bakchich, 28 July 2008

- ↑ Antoine Albertini, Trafic de cannabis : Gilbert Casanova, ex-figure du nationalisme corse, interpellé, Le Monde, 24 June 2008

- ↑ Frank McLynn (1998). Napoleon. Pimlico. ISBN 0712662472.

External links

- Les plumes du paon (in French): Site with many sources, including much unpublished material regarding the Corsican question

- Corsican-Myths: Mirror site of the site above, totally translated in English with new unpublished material regarding the Corsican question and more

- Unita Naziunale (in French): Corsican nationalist website presenting a number of analyses explaining action against villas on the Corsican coast

- Corsica Nazione Indipendente (in French): Website of Corsican nationalist movement