Coronation of Napoleon I

| |

| Date |

December 2, 1804 (11 Frimaire XIII) |

|---|---|

| Location | Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris |

The coronation of Napoleon as Emperor of the French took place on Sunday December 2, 1804 (11 Frimaire, Year XIII according to the French Republican Calendar) at Notre Dame Cathedral in Paris. It marked "the instantiation of modern empire" and was a "transparently masterminded piece of modern propaganda".[1]

Napoleon wanted to establish legitimacy of his imperial reign, with its new royal family and new nobility. Therefore, he designed a new coronation ceremony that was unlike the ceremony used for the kings of France. In the traditional coronation, the act of the king's consecration (sacre) was emphasised, and anointment was conferred by the archbishop of Reims in the Cathedral Notre-Dame de Reims.[2] Napoleon's was a sacred ceremony held in the great cathedral of Notre Dame de Paris in the presence of Pope Pius VII. Napoleon brought together an assortment of different rites and customs, incorporating aspects of Carolingian tradition, the ancien régime and the French Revolution, all presented in sumptuous luxury.[3] According to government tallies, the entire cost was over 8.5 million francs.

On May 18, 1804, the Sénat conservateur vested the Republican government of the French First Republic in an Emperor, and preparations for a coronation followed. Napoleon's elevation to Emperor was overwhelmingly approved by the French citizens in the French constitutional referendum of 1804. Among Napoleon's motivations for being crowned were to gain prestige in international royalist and Catholic milieux and to lay the foundation for a future dynasty.[2]:243

Preparations

When Pope Pius VII agreed to come to Paris to officiate at Napoleon's Coronation, it was initially established that the crowning would follow the Roman Coronation liturgy contained in the Roman Pontifical. However, after the Pope's arrival in France, Napoleon persuaded the Papal delegation to allow the introdution of several French elements in the rite - such as the singing of the Veni Creator for the monarch's entrance procession, the use of Chrism instead of the Oil of Catechumens for the anointing (although the Roman anointing prayers were used), the performance of the anointings at the head and hands, and not at the right arm and back of the neck, and the inclusion in the rite of several prayers and formulas borrowed from the French ceremonial for the Coronation of Kings, that were used for the blessing of the items of regalia and for the delivery of the said items. Thus, in essence a new rite was composed for the occasion, unique to the Coronation of Napoleon[4], combining French and Roman elements in a new manner, specific to that particular Coronation. Also, the special rite that was composed ad hoc for the occasion allowed Napoleon to remain mostly seated and not kneeling during the delivery of the regalia and during several other ceremonies, and reduced his acceptance of the oath demanded by the Church in the beginning of the liturgy to one word only.

Not wanting to be an Old Regime monarch, Napoleon explained: "To be a king is to inherit old ideas and genealogy. I don't want to descend from anyone." According to Louis Constant Wairy, Napoleon awoke at 8:00 a.m. To the sound of a cannonade, he left the Tuileries at 11:00 a.m. in a white velvet vest with gold embroidery and diamond buttons, a crimson velvet tunic and a short crimson coat with satin lining. He wore a wreath of laurel.[5]:54 The number of onlookers, as estimated by Wairy, was between four and five thousand, many of whom had held their places all night, through intermittent showers that cleared in the morning.[6]:301

Ceremony

.jpg)

The ceremony had started at 9 a.m. when the Papal procession set out from the Tuileries. The procession was led by a bishop on a mule holding aloft the Papal crucifix.[7] The Pope entered Notre Dame first, to the anthem Tu es Petrus, and took his seat on a throne near the high altar.[5] Napoleon's and Joséphine's carriage was drawn by eight bay horses and escorted by grenadiers à cheval and gendarmes d'élite.[8] The two-part ceremony was held at different ends of Notre Dame to emphasize the disconnectedness of religious and secular facets. An unmanned balloon, ablaze with three thousand lights in an imperial crown pattern, was launched from the front of Notre Dame during the celebration.[7]

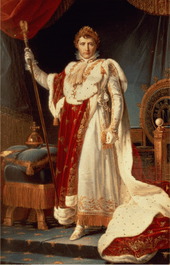

Before entering Notre Dame, Napoleon was vested in a long white satin tunic embroidered in gold thread and Josephine similarly wore a white satin empire style dress embroidered in gold thread. During the coronation he was formally clothed in a heavy coronation mantle, made from crimson velvet and lined with ermine; the velvet was covered with embroidered golden bees, drawn from the golden bees among the regalia that had been discovered in the Merovingian tomb of Childeric I, a symbol that looked beyond the Bourbon past and linked the new dynasty with the ancient Merovingians; the bee replaced the fleur-de-lis on imperial tapestries and garments. The mantle weighed at least eighty pounds and was supported by four dignitaries.[6]:299 Josephine was at the same time formally clothed in a similar crimson velvet mantle embroidered with bees in gold thread and lined with ermine, which was borne by Napoleon's three sisters.[nb 1] There were two orchestras with four choruses, numerous military bands playing heroic marches, and over three hundred musicians.[6]:302 A 400-voice choir performed Paisiello's "Mass" and "Te Deum". Because the traditional royal crown had been destroyed during the French Revolution, the so-called Crown of Napoleon, made to look medieval and called the "crown of Charlemagne" for the occasion,[5]:55 was waiting on the altar. While the crown was new, the sceptre was reputed to have belonged to Charles V and the sword to Philip III.

The coronation proper began with the singing of the hymn, Veni Creator Spiritus, followed by the versicle, "Lord, send forth your Spirit" and response, "And renew the face of the earth" and the collect for the Feast of Pentecost, "God, who has taught the hearts of your faithful by sending them the light of your Holy Spirit,..." After this the prayer, "Almighty, everlasting God, the Creator of all..."[nb 2] During the Litany of the Saints, the Emperor and Empress remained seated, only kneeling for special petitions. The Emperor and Empress were both anointed on their heads and on both hands with chrism–the Emperor with the prayers, "God, the Son of God..."[4][nb 3] and "God who established Hazael over Syria...",[4] the Empress with the prayer, "God the Father of eternal glory..."—while the antiphon Unxerunt Salomonem Sadoc Sacerdos... ("Zadok the priest...") was sung. The Mass then began. At Napoleon's request, the collect of the Blessed Virgin (as the patron of the cathedral) was said in place of the proper collect for the day. After the epistle the different articles of the imperial regalia were individually blessed,[nb 4] and delivered[nb 5] to the Emperor and Empress.[nb 6]

For the crowning, as recorded in the official procès-verbal of the Coronation[9] the French formula Coronet te Deus... (God crown you with a crown of glory and righteousness...) - a formula that is also proper to the English Coronation rite - was used exclusively, instead of the Roman formula Accipe coronam... (Receive the crown...). This differed to the usage of the French royal coronations, in which both formulas - the Anglo-French Coronet te Deus... and the Roman Accipe coronam regni... - were recited one after the other. While the Pope recited the above-mentioned formula,Napoleon turned and removed his laurel wreath and crowned himself and then crowned the kneeling Joséphine with a small crown surmounted by a cross, which he had first placed on his own head.[4] The omission of the Roman formula Accipe coronam... at this point is probably due to the fact that it specified that the monarch was being crowned by the bishops, representatives of the Church, and thus such prayer would not fit with Napoleon's decision to crown himself. Historian J. David Markham, who also serves as head of the International Napoleonic Society,[10] alleged in his book Napoleon For Dummies "Napoleon's detractors like to say that he snatched the crown from the Pope, or that this was an act of unbelievable arrogance, but neither of those charges holds water. Napoleon was simply symbolizing that he was becoming emperor based on his own merits and the will of the people, not because of some religious consecration. Originally, the crown of Louis XV of France supposed to have completed collection of Mazarin Diamonds, the Sancy diamond in the fleur-de-lis at the top of the arches, and the 'Regent' diamond, as well as hundreds of other precious diamonds, rubies, emeralds and sapphires. However, Sancy diamond was not in the crown on the day of coronation. It was in collection of Vasily Rudanovsky - Russian art collector, who bought a diamond during the French revolution and then in 1828 sold it to Prince Demidoff. Despite the fact that Napoleon managed to return the “Regent” diamond from Russia, the absence of “Sancy” was irritating. Diamond gave the crown a sacred royal meaning, without it the Pope risked being ridiculed by Napoleon’s court. The Pope knew about this move from the beginning and had no objection (not that it would have mattered)."[11] British historian Vincent Cronin wrote in his book Napoleon Bonaparte: An Intimate Biography "Napoleon told Pius that he would be placing the crown on his own head. Pius raised no objection."[12] At Napoleon's enthronement the Pope said, "May God confirm you on this throne and may Christ give you to rule with him in his eternal kingdom".[nb 7] Limited in his actions, Pius VII proclaimed further the Latin formula Vivat imperator in aeternum! ("May the Emperor live forever!"), which was echoed by the full choirs in a Vivat, followed by "Te Deum". After the Mass was finished, the Pope retired to the Sacristy, as he objected to presiding over or witnessing the taking of the civil oath that followed, due to its contents. With his hands on the Bible, Napoleon took the oath:

I swear to maintain the integrity of the territory of the Republic, to respect and enforce respect for the Concordat and freedom of religion, equality of rights, political and civil liberty, the irrevocability of the sale of national lands; not to raise any tax except in virtue of the law; to maintain the institution of Legion of Honor and to govern in the sole interest, happiness and glory of the French people.[2]:245

The text was presented to Napoleon by the President of the Senate, the President of Legislature and the most senior President of the Council of State. After the oath the newly appointed herald of arms proclaimed loudly: "The thrice glorious and thrice august Emperor Napoleon is crowned and enthroned. Long live the Emperor!"[13] During the people's acclamations Napoleon, surrounded by dignitaries, left the cathedral while the choir sang "Domine salvum fac imperatorem nostrum Napoleonem"—"God save our Emperor Napoleon".

After the coronation the Emperor presented the imperial standards to each of his regiments.

In addition to David's paintings, a commemorative medal was struck with the reverse design by Antoine-Denis Chaudet. A computer model visualising the coronation was made by Vaughan Hart, Peter Hicks and Joe Robson for the "Nelson and Napoleon" Exhibition held at the National Maritime Museum in 2005.[14]

See also

Notes

- ↑ There is an anecdotal account that just as Josephine reached the top of the steps of the high altar to be crowned, Napoleon's sisters deliberately gave her mantle a sudden tug which momentarily caused her to lose her balance, but she did not fall as her sisters-in-law had intended.

- ↑ With the substitution of the word "emperor" for "king" and the addition of the words "and of his consort" to the original prayer from the traditional French coronation ritual.[4]

- ↑ A translation of this prayer may be found at Coronation of the Hungarian monarch

- ↑ The blessings for the sword, rings, gloves, the Hand of Justice and the scepter were taken from the Cérémoniel françois, while the blessing of the orb was special composed for the occasion.[4]

- ↑ The forms for the delivery of the sword, rings, gloves, Hand of Justice and the scepter were also from the Cérémoniel françois, while that for the delivery of the mantles and the Orb were also specially composed for the occasion.[4]

- ↑ The forms for the delivery of the rings and the mantles were in the plural, since they were given to the Emperor and Empress simultaneously.[4]

- ↑ This enthronement formula was a new composition, different from all the variations of the traditional "Sta et retine..." formula usually employed in Western Coronation rites; even the starting words of the formula were different, and in all probability the traditional prayer was abandoned because it specified too clearly that the monarch received the Throne from the bishops and was a mediator between clergy and people. The new formula used for Napoleon's enthronement avoided any mention of this.

References

- ↑ Porterfield, Todd Burke; Siegfried, Susan L. (2006). Staging empire: Napoleon, Ingres, and David. Penn State Press. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-271-02858-3. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Englund, Steven (2005-04-30). Napoleon: A Political Life. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01803-7. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- ↑ Dwyer 2015

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Woolley, Reginald Maxwell (1915). Coronation Rites. Cambridge University Press. pp. 106–107.

- 1 2 3 Junot, Laure, duchesse d'Abrantès (1836). Memoirs of Napoleon, his court and family. 2. R. Bentley. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- 1 2 3 Wairy, Louis Constant (1895). Recollections of the private life of Napoleon. 1. The Merriam company. Retrieved 1 December 2011.

- 1 2 Napoleon's Coronation as Emperor of the French Georgian Index

- ↑ Bernard Picart, "Histoire des religions et des moeurs de tous les peuples du monde, Volume 5", Paris, 1819, p.293

- ↑ https://archive.org/details/bub_gb_rorP0Chzx78C

- ↑ http://www.napoleonichistory.com/

- ↑ Markham, J. David, Napoleon for Dummies, 2005, p. 286

- ↑ Cronin, Vincent, Napoleon, 1971, p. 250

- ↑ Sloane, William Milligan (1910). The Life of Napoleon Bonaparte. The Century Co. p. 344. Retrieved 30 November 2017.

- ↑ Peter Hicks (10 December 2009). "Coronation and consecration of Napoleon I" – via YouTube.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Coronation of Napoleon I. |

- Dwyer, Philip. "Citizen Emperor’: Political Ritual, Popular Sovereignty and the Coronation of Napoleon I," History (2015) 100#339 pp 40–57, online

- Masson, Frederic; Cobb. Frederic (translator). Napoleon and his Coronation. London, 1911