Copland (operating system)

| Developer | Apple Computer, Inc. |

|---|---|

| OS family | Macintosh |

| Working state | Discontinued |

| Source model | Closed source |

| Final preview | Developer Release 1 |

| Marketing target | Macintosh users |

| Platforms | Power Macintosh |

| Kernel type | Microkernel |

| Preceded by | System 7 |

| Succeeded by | Mac OS X |

Copland is an unreleased operating system prototype for Apple Macintosh computers of the late 1990s, intended to be released as the modern System 8 successor to the aging but venerable System 7. It introduced protected memory, preemptive multitasking, and a number of new underlying operating system features, while retaining compatibility with existing Mac applications. Copland's planned successor, codenamed Gershwin, was intended to add advanced features such as application-level multithreading.

Across a protracted development period of several years, previews of Copland garnered much press that introduced the layperson Macintosh audience to basic concepts of modern operating system design such as object orientation, crash-proofing, and multitasking. The project was Apple's trigger to cofound several industry-wide standards and consortiums for next-generation operating system development, such as OpenDoc and Taligent.

Copland reached Developer Release beta testing status before its cancellation in August 1996. Instead, Apple released a much more legacy-oriented Mac OS 8 in 1997, followed by Mac OS 9's architectural improvements in 1999, and then Mac OS X became Apple's next-generation operating system release in 2001. All of these releases bear some functional or cosmetic influence from Copland.

As a product of dysfunctional corporate personnel and project management, Copland is associated with empire-building, feature creep, and project death march. In 2008, PC World named Copland on a list of the biggest project failures in IT history.[1]

Design

Mac OS legacy

The pre-history of Copland begins with an understanding of the Mac OS legacy, and its architectural problems to be solved.

Launched in 1984, the Macintosh and its operating system were designed from the beginning as a single-user, single-tasking machine, which allowed the hardware development to be greatly simplified.[2] As a side effect of this single application model, the original Mac developers were able to take advantage of a number of compromising simplifications that allowed great improvements in performance, running even faster than the much more expensive Lisa. But this design also led to several problems for future expansion.

By assuming only one program would be running at a time, the engineers were able to ignore the concept of reentrancy; the ability for a program (or library) to be stopped at any point, asked to do something else, and then return to the original task. In the case of QuickDraw for example, this means the system can store state information internally, like the current location of the window or the line style, knowing it would only change under control of the running program. Taking this one step further, the engineers left most of this state inside the application rather than in QuickDraw, thus eliminating the need to copy this data between the application and library.

The other main issue was that early Macs lack a memory management unit (MMU), which precludes the possibility of several fundamental modern features. An MMU would provide memory protection to ensure that programs cannot accidentally overwrite other program's memory, and it would provision shared memory. Lacking shared memory, the API was instead written so the operating system and application shares all memory, which is what allows QuickDraw to examine the application's memory for settings like the line drawing mode or color.

These limitations mean that supporting the multitasking of more than one program at a time would be difficult, without rewriting all of this operating system and application code. Yet doing so, would mean the system would run unacceptably slow on existing hardware. Instead, Apple adopted a system known as MultiFinder in 1987, which keeps the running application in control of the computer as before but allows an application to be rapidly switched to another, normally simply by clicking on its window. Programs that are not in the foreground are periodically given short bits of time to run, but as before, the entire process is controlled by the applications, not the operating system.

Because the operating system and applications all share a single memory space, it is possible for a bug in any one of them to corrupt the entire operating system, and crash the machine. This is not particularly annoying under a single-application model, in which case the application crashes anyway. But under MultiFinder, any crash will crash all the other running programs as well. The multitasking of multiple applications potentially increases the chances of a crash, making the system potentially more fragile.

Adding greatly to the severity of the problem, is the system used to add functionality to the operating system itself, which relies on a patching mechanism known as CDEVs and INITs, commonly known as Control Panels, and Extensions. Third party developers also make use of this mechanism to add features, including screensavers and a hierarchal Apple menu, independently of Apple. Some of these third-party control panels became almost universal, like the popular After Dark screensaver package.[4] Since there was no standard for use of these patches, it is not uncommon for several of these add-ons—including Apple's own additions to the OS—to use the same patches, and interfere with each other, leading to more crashing.

Copland design

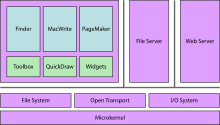

Copland was designed to consist of the Mac OS on top of a microkernel named Nukernel, which would handle basic tasks such as application startup and memory management, leaving all other tasks to a series of semi-special programs known as servers. For instance, networking and file services would not be provided by the kernel itself, but by servers that would be sent requests though interapplication communications.[5] Copland consists of the combination of Nukernel, various servers, and a suite of application support libraries to provide implementations of the well-known classic Macintosh programming interface.[6]

Application services are offered through a single program known officially as the Cooperative Macintosh Toolbox environment,[6] but are universally referred to as the Blue Box. The Blue Box encapsulates an existing System 7 operating system inside a single process and address space. Mac programs run inside the Blue Box much as they do under System 7,[7] as cooperative tasks that use the non-reentrant Toolbox calls. A worst-case scenario is that an application in the Blue Box crashes, taking down the entire Blue Box instance with it. This does not result in the system as a whole going down, however, and the Blue Box can be restarted.

New applications written with Copland in mind, are able to directly communicate with the system servers and thereby gain many advantages in terms of performance and scalability. They can also communicate with the kernel to launch separate applications or threads, which run as separate processes in protected memory, as in most modern operating systems. These separate applications cannot use non-reentrant calls like QuickDraw, however, and thus could have no user interface. Apple suggested that larger programs could place their user interface in a normal Macintosh application, which would then start "worker threads" externally.[6]

Another key feature of Copland is that it is completely PowerPC native. System 7 had been ported to the PowerPC (PPC) with great success; large portions of the system run as PPC code—including both high-level functionality, such as the majority of the user interface "toolbox" managers, and low-level functionality, such as interrupt management. There is enough 68k code left in the system to be run in emulation, and especially user applications, however that the operating system must map some data between the two environments. In particular, every call into the Mac OS requires a mapping between the 68k's interrupt system and the PPC's. Removing these mappings would greatly improve general system performance; at WWDC 1996, engineers claimed that the performance of system calls would be as much as 50% faster.[8]

Copland is also based on the newly defined Common Hardware Reference Platform, or CHRP, which standardized the Mac hardware to the point where it could be built by different companies and can run other operating systems (Solaris and AIX were two of many mentioned). This was a common theme at the time; many companies were forming groups to define standardized platforms to offer an alternative to the "Wintel" platform that was rapidly becoming dominant—examples include 88open, Advanced Computing Environment, and the AIM alliance.[9]

The challenge in Copland would be getting all of this functionality to fit into an ordinary Mac. System 7.5 already uses up about 2.5 megabytes (MB) of RAM, and at the time this was a significant portion of the total RAM in most machines. Copland runs what was essentially a complete copy of System 7.5 (in the Blue Box) in addition to an entirely separate operating system running under it. Copland therefore uses a Mach-inspired memory management system and relies extensively upon shared libraries,[10] with the goal being for Copland to be only some 50% larger than 7.5.

History

Copland's development began in 1994 and was underway in earnest by 1995 when the system started to be referred to as "System 8", and later, "Mac OS 8". It was the major topic of Apple's Apple Worldwide Developers Conference in 1996, where it was presented as the sole focus of the company's development efforts. As the project gathered momentum, however, a furious round of internal corporate empire building began. New features were added more rapidly than they could be completed, including most of the items originally slated for Gershwin, along with a wide variety of otherwise unrelated projects from within the company. The completion date for the beta continued to slip into the future and several announced dates passed with no sign of a release. The press became highly critical of the project, and of the company as a whole.

In 1996, Apple's newest CEO, Gil Amelio, poached Ellen Hancock from National Semiconductor and put her in charge of engineering in an effort to try to get development back on track. She decided it was best to cancel the project outright and try to find a suitable third-party system to replace it. Development of Copland officially ended in August 1996. After a short search, Apple announced its purchase of NeXT in order to use its NeXTSTEP operating system as the basis of a new Mac OS. Hancock also suggested that Apple should work on improving the existing System 7 while the new system matured. This was released as Mac OS 8 in 1997 and was followed by Mac OS 9 in 1999. The new operating system based on NeXTSTEP shipped in 2001 as Mac OS X.

Pink and Blue

In March 1988,[lower-alpha 1] technical middle managers at Apple held an offsite meeting to plan the future course of Mac OS development.[11] Ideas were written on index cards; features that seemed simple enough to implement in the short term (like adding color to the user interface) were written on blue cards; longer-term goals—such as preemptive multitasking—were on pink cards; and long-range ideas like an object-oriented file system were on red cards.[12][13] Development of the ideas contained on the blue and pink cards was to proceed in parallel, and at first, the two projects were known simply as "blue" and "pink".[14] Apple intended to have the "blue" team (which came to call themselves the "Blue Meanies" after characters in Yellow Submarine)[15] release an updated version of the existing Macintosh operating system in the 1990–1991 timeframe, and the Pink team to release an entirely new OS around 1993.

The Blue team delivered what became known as System 7 on May 13, 1991, but the Pink team suffered from second-system effect and its release date continued to slip into the indefinite future. Some of the reason for this can be traced to problems that would become widespread at Apple, as time went on; as Pink became delayed and its engineers moved to Blue instead.[16] This left the Pink team constantly struggling for staffing, and suffering from the problems associated with high employee turnover. Management ignored these sorts of technical development issues, leading to continual problems delivering working products.

At this same time, the recently released NeXTSTEP was generating intense interest in the developer world. Features that were originally part of Red, were folded into Pink, and the Red project (also known as "Raptor")[17] was eventually canceled. This problem was also common at Apple during this period; in order to chase the "next big thing", middle managers would add new features to their projects with little oversight, leading to enormous problems with feature creep. In the case of Pink, development eventually slowed to the point the project appeared moribund.

Taligent

On April 12, 1991, Apple CEO John Sculley performed a secret demonstration of Pink running on an PS/2 Model 70 to a delegation from IBM. Though the system was not fully functional, it resembled System 7 running on a PC. IBM was extremely interested, and over the next few months, the two companies formed an alliance to further development of the system. These efforts became public in early 1992, under the new name "Taligent".[18] At the time, Sculley summed up his concerns with Apple's own ability to ship Pink when he stated "We want to be a major player in the computer industry, not a niche player. The only way to do that is to work with another major player."[19]

Infighting at the new joint company was legendary, and the problems with Pink within Apple soon appeared to be minor in comparison.[20] Apple employees made T-shirts, graphically displaying their prediction that the result would be an IBM-only project,[21] a prediction that came true on December 19, 1995, when Apple officially pulled out of the project.[22] IBM continued working with Taligent, and eventually released its application development portions under the new name "CommonPoint". This saw little interest and the project disappeared from IBM's catalogs within months.

Business as usual

While Taligent efforts continued, very little work addressing the structure of the original OS was carried out. Several new projects started during this time. Notably the Star Trek project is the code name of a port of System 7 and its basic applications, running on an Intel-compatible x86 machine, which reached demo quality. But as Taligent was still a going concern, it was difficult for new OS projects to gain any traction.

Instead, Apple's Blue team continued adding new features to the same basic OS. During the early 1990s Apple released a series of major new packages to the system; amongst them were QuickDraw GX, Open Transport, OpenDoc, PowerTalk, and many others. Most of these were larger than the original operating system. Problems with stability that had existed even with small patches, grew along with the size and requirements of these packages, and by the mid-1990s the Mac had a reputation for instability and constant crashing.[6]

As the stability of the operating system collapsed, the ready answer was that Taligent would fix this—it was fully reentrant, truly multitasking, and made heavy use of protected memory. When the Taligent efforts collapsed, Apple was left with an aging OS and no designated solutions. By 1994 the press buzz surrounding the upcoming release of Windows 95 started to grow to a crescendo, often questioning Apple's ability to respond to the challenge it presented.[13] The press turned on the company, often introducing Apple's new projects as failures in the making.[23]

Another try

Given this pressure, the collapse of Taligent, the growing problems with the existing operating system, and the release of System 7.5 in late 1994, Apple management decided that the decade-old operating system had run its course. A new system that did not have these problems was needed, and soon. Since so much of the existing system would be difficult to rewrite, Apple developed a two-stage approach to the problem.

In the first stage, the existing system would be moved on top of a new kernel-based OS with built-in support for multitasking and protected memory. The existing libraries, like QuickDraw, would take too long to be rewritten for the new system and would not be converted to be reentrant. Instead, a single paravirtualized operating system, the "Blue Box", keeps applications and older code like QuickDraw in a single memory block so they continue to run as they had in the past. The Blue Box operating system itself runs in a separate memory space, so crashing applications or extensions within Blue Box can not crash the entire machine.

Once the new kernel was in place and this basic upgrade was released, development would move on to rewriting the older libraries into new forms that could run directly over the new kernel.[24][25] At that point, applications would gain some additional modern features.

As System 7.5 was code-named "Mozart", the next-generation operating system was intended to address the looming architectural issues, was dubbed "Copland" after composer Aaron Copland. The intended successor system, "Gershwin", would complete the process of moving the entire system to the new platform.

Development

The Copland project was first announced in March 1995.[26] Parts of Copland, most notably an early version of the new file system, were demonstrated at Apple's Worldwide Developers Conference in May 1995. Apple also promised that a beta release of Copland would be ready by the end of the year, for final commercial release in early 1996.[26][27] Gershwin would follow the next year.[28] Throughout the year, Apple released a number of mock-ups to various magazines showing what the new system would look like, and commented continually that the company was fully committed to this project. By the end of the year, however, the Developer Release had not been produced.[27]

As had happened in the past during the development of Pink, developers within Apple soon started abandoning their own projects in order to work on the new system. Middle management and project leaders fought back by claiming that their project was vital to the success of the system, and moving it into the Copland development stream. Thus, it could not be canceled along with their employees being removed to work on some other part of Copland anyway.[1] This process took on momentum across the next year.

"Anytime they saw something sexy it had to go into the OS," said Jeffrey Tarter, publisher of the software industry newsletter Softletter. "There were little groups all over Apple doing fun things that had no earthly application to Apple's product line." What resulted was a vicious cycle: As the addition of features pushed back deadlines, Apple was compelled to promise still more functions to justify the costly delays. Moreover, this Sisyphean pattern persisted at a time when the company could scarcely afford to miss a step.[26]

In mid-1996, information was leaked that Copland would have the ability to run applications written for other operating systems including Windows NT. This feature had supposedly been in development for more than 3 years. One user claimed to have been told about these plans by members of the Copland development team. Some analysts projected that this ability would increase Apple's penetration into the enterprise market, others said it was "game over" and was only a sign of the Mac platform's irrelevancy.[29]

Soon the project looked less like a new operating system and more like a huge collection of new technologies; QuickDraw GX, SOM, and OpenDoc became core components of the system,[30] while completely unrelated technologies like a new file management dialog box (the "open dialog") and "themes" support appeared as well. The feature list grew much faster than the features could be completed, a classic case of creeping featuritis.[26]

An industry executive noted that "The game is to cut it down to the three or four most compelling features as opposed to having hundreds of nice-to-haves, I'm not sure that's happening."[31]

As the "package" grew, testing it became increasingly difficult and engineers were commenting as early as 1995 that Apple's announced 1996 release date was hopelessly optimistic: "There's no way in hell Copland ships next year. I just hope it ships in 1997."[31]

Developer Release

At WWDC 1996, Apple's new CEO, Gil Amelio, used the keynote to talk almost exclusively about Copland, now known as System 8. He repeatedly stated that it was the only focus of Apple engineering and that it would ship to developers at the end of summer with a full release planned for late fall. Very few, if any, demos of the running system were shown at the conference. Instead, various pieces of the technology and user interface that would go into the package (such as a new file management dialog) were demonstrated. Little of the core system's technology was demonstrated and the new file system that had been shown a year earlier was absent.

There was one way to actually use the new operating system, by signing up for time in the developer labs. This did not go well:

There was a hands-on demo of the current state of OS 8. There were tantalizing glimpses of the goodies to come, but the overall experience was awful. It does not yet support text editing, so you couldn’t actually do anything except open and view documents (any dialog field that needed something typed into it was blank and dead).

Also, it was incredibly fragile and crashed repeatedly, often corrupting system files on the disk in the process. The demo staff reformatted and rebuilt the hard disks at regular intervals. It was incredible that they even let us see the beast.[32]

After a number of people at the show complained about the microkernel's lack of sophistication, notably the lack of symmetric multiprocessing—a feature that would be exceedingly difficult to add to a system due to ship in a few months—Amelio came back on stage and announced that they would be adding that to the feature list.

In August 1996, "Developer Release 0" was sent to a small number of selected partners.[26] Far from demonstrating improved stability, it often crashed after doing nothing at all, and was completely unusable for development. In October, Apple moved the target delivery date to "sometime", hinting that it might be 1997. One of the groups most surprised by the announcement was Apple's own hardware team, who had been waiting for Copland to allow the PowerPC be truly represented, unburdened of software legacy. Members of Apple's software QA team suggested, jokingly, that given current resources and the number of bugs in the system they could clear the program for shipping sometime around 2030.

Cancellation

Later that summer, the situation was no better. Amelio complained that Copland was "just a collection of separate pieces, each being worked on by a different team ... that were expected to magically come together somehow."[33] Hoping to salvage the situation, Amelio hired Ellen Hancock away from National Semiconductor to take over engineering and get Copland development back on track.[34]

After a few months on the job, Hancock came to the conclusion that the situation was hopeless; given current development and engineering, she felt Copland would never ship. Instead, she suggested that the various user-facing technologies in Copland be rolled out in a series of staged releases, instead of a single big release. To address the aging infrastructure below these technologies, Amelio suggested looking outside the company for an entirely new operating system. Candidates considered were Sun's Solaris and Windows NT. Hancock reportedly was in favor of going with Solaris, while Amelio preferred Windows. Amelio even reportedly called Bill Gates to discuss the idea, and Gates promised to put Microsoft engineers to work porting QuickDraw to NT.[35]

Apple officially canceled Copland in August 1996.[28] While the CD envelopes for the developer's release had been printed, the discs themselves had not been mastered.

After lengthy discussions with Be and rumors of a merger with Sun Microsystems, many were surprised at Apple's December 1996 announcement that they were purchasing NeXT and bringing Steve Jobs on in an advisory role.[36] Amelio quipped that they "choose Plan A instead of Plan Be."[37] The project to port OpenStep to the Macintosh platform was named Rhapsody and was to be the core of Apple's cross-platform operating system strategy. This would inherit OpenStep's existing support for Power PC, Intel x86, and DEC Alpha CPU architectures, as well as an implementation of the OPENSTEP libraries running on Windows NT. This would in effect open the Windows application market to Macintosh developers as they could license the library from Apple for distribution with their product, or depend upon a preexisting installation.

Legacy

Following Hancock's plan, development of System 7.5 continued, with a number of technologies originally slated for Copland being incorporated into the base OS. Apple embarked on a buying campaign, acquiring the rights to various third-party system enhancements and integrating them into the OS. The Extensions Manager, hierarchical Apple menu, collapsing windows, the menu bar clock, and sticky notes—all were developed outside of Apple. Stability and performance were improved by Mac OS 7.6, which dropped the "System" moniker in favor of "Mac OS".[38] Eventually, many features developed for Copland, including the new multithreaded Finder and support for themes (the default Platinum was the only theme included) were rolled into the unreleased beta of Mac OS 7.7, which was instead rebranded and launched as Mac OS 8.

With the return of Jobs, this rebranding to version 8 also allowed Apple to exploit a legal loophole to terminate third-party manufacturers' licenses to System 7 and effectively shut down the Macintosh clone market.[39] Later, Mac OS 8.1 finally added the new filesystem and Mac OS 8.6 updated the nanokernel to handle limited support for preemptive tasks. Its interface is Multiprocessing Services 2.x and later, but there is no process separation and the system still uses cooperative multitasking between processes. Even a process that is Multiprocessing Services-aware still has a portion that runs in the Blue Box—a task that also runs all single-threaded programs and the only task that can run 68k code.

The Rhapsody project was cancelled after several Developer Preview releases, support for running on non-Macintosh platforms was dropped, and it was eventually released as Mac OS X Server 1.0. In 2001 this foundation was coupled to the Carbon library and Aqua user interface to form the modern Mac OS X product. Versions of Mac OS X prior to the Intel release of Mac OS X 10.4 (Tiger), also use the rootless Blue Box concept in the form of Classic to run applications written for older versions of Mac OS. A number of features originally seen in Copland demos, including its advanced Find command, built-in Internet browser, "piles" of folders, and support for video-conferencing, have reappeared in subsequent releases of Mac OS X as Spotlight, Safari, Stacks, and iChat AV, respectively, although the implementation and user interface for each feature is completely different.

Hardware requirements

According to the documentation included in the Developer Release, Copland supports the following hardware configurations:[40]

- NuBus-based Macintoshes: 6100/60, 6100/60AV (no AV functionality), 6100/66, 6100/66 AV (no AV functionality), 6100/66 DOS (no DOS functionality), 7100/66, 7100/66 AV (no AV functionality), 7100/80, 7100/80 AV (no AV functionality), 8100/80/ 8100/100/ 8100/100 AV (no AV functionality), 8100/110

- NuBus-based Performas: 6110CD, 6112CD, 6115CD, 6117CD, 6118CD

- PCI-based Macintoshes: 7200/70, 7200/90, 7500/100, 8500/120, 9500/120, 9500/132

- Drives formatted with Drive Setup (other initialization software may work; if you have trouble, try reinitializing with Drive Setup 1.0.4 or later).

- For builds up to and including DR1, the installer is set to ensure you have System 7.5 or later on a hard disk 250MB or greater.

- Monitors connected to either built-in video or a card set to 256 colors (8-bit) or Thousands (16-bit).

See also

Notes

References

Citations

- 1 2 Widman, Jake (October 9, 2008). "Lessons Learned: IT's Biggest Project Failures". PCWorld. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- ↑ "30 years of the Apple Lisa and the Apple IIe".

- ↑ Adam Brooks Webber, the programmer responsible for porting TrueBASIC to the Amiga and Macintosh, Amiga vs. Macintosh, Byte Sept. 1986

- ↑ Engst, Adam C. (June 9, 2003). "After Dark Returns for Mac OS X". Tidbits. Ithaca, New York. Retrieved September 11, 2013.

- ↑ Francis 1996, p. 32.

- 1 2 3 4 Dierks 1995.

- ↑ Falkenburg 1996.

- ↑ Francis 1996, p. 9, 18.

- ↑ Francis 1996, p. 9.

- ↑ Francis 1996, pp. 19, 20.

- 1 2 Carlton 1997, p. 96.

- ↑ Carlton 1997, pp. 96-98.

- 1 2 Singh 2007, p. 2.

- ↑ Carlton 1997, p. 167.

- ↑ Carlton 1997, p. 169.

- ↑ Carlton 1997, p. 99.

- ↑ Singh 2007, p. 4.

- ↑ "'Pink' may get a pink slip". Business Week: 40. 1993.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, p. 69.

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, pp. 70, 230.

- ↑ Gordon Thygeson, "Apple T-shirts: a yearbook of history at Apple computer", Pomo Pub, 1997, pp. 44–48

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, p. 81.

- ↑ Quinlan, Tom (July 11, 1994). "Apple set to ship System 7.5". InfoWorld: 6.

- ↑ Michael J. Miller (October 4, 1995). "Beyond Windows 95". PC Magazine. Retrieved July 23, 2006.

- ↑ Henry Bortman; Jeff Pittelkau (January 1997). "Plan Be". MacUser. Retrieved July 23, 2006.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Mac's new OS: Seven years in the making" cnet, March 21, 2001

- 1 2 Crabbe 1995.

- 1 2 "The Long and Winding Road", MacWorld, September 1, 2000

- ↑ "Computerworld Jul 29, 1996".

- ↑ Duncan 1994.

- 1 2 Burrows 1995.

- ↑ "WWDC'96: Looking for the Future", MacTECH, Volume 12 Issue 9 (August 1996)

- ↑ Gil Amelio and William Simon, "On the Firing Line", Harper, 1998

- ↑ Carlton 1997, p. 402.

- ↑ "The Rise and Fall of Apple's Gil Amelio".

- ↑ Dawn Kawamoto, Mike Yamamoto and Jeff Pelline, "Apple acquires Next, Jobs", cnet December 20, 1996

- ↑ Linzmayer 2004, p. 277.

- ↑ Singh 2007, p. 6.

- ↑ Beale, Steven (October 1997). "Mac OS 8 Ships with No License Deal". Macworld. 14 (10). pp. 34–36.

- ↑ How to Install Mac OS 8 (D11E4), "Hardware Supported" section

- ↑ Cotter 1995, p. XIII.

- ↑ Cotter 1995, p. 6.

- ↑ Linzmayer 1997, p. 35.

- ↑ Linzmayer 1997, p. 47.

Bibliography

- Burrows, Peter (December 18, 1995). "Apple's Copland: NEW! IMPROVED! NOT HERE YET!". BusinessWeek.

- Carlton, Jim (1997). Apple: the inside story of intrigue, egomania, and business blunders. Times Business/Random House. ISBN 0-8129-2851-2.

- Crabbe, Don (December 1995). "Copland, Where Are Thee?". MacTECH. Vol. 11 no. 12.

- Dierks, Tim (June 1995). "Copland: The Mac OS Moves Into the Future". develop. No. 22.

- Duncan, Geoff (December 12, 1994). "OS Directions: Marconi, Copland, and Gershwin". TidBITS.

- Falkenburg, Steve (June 1996). "Planning for Mac OS 8 Compatibility". develop. No. 26.

- Francis, Tony (1996). Mac OS 8 Revealed (PDF). Addison-Wesley.

- Linzmayer, Owen (2004). Apple Confidential 2.0: The Definitive History of the World's Most Colorful Company. No Starch Press. ISBN 1-59327-010-0.

- Singh, Amit (2007). Mac OS X internals: a systems approach. Addison-Wesley.

- Cotter, Sean (1995). Inside Taligent Technology. Addison-Wesley. ISBN 0-201-40970-4.

External links

- Apple's Copland project: An OS for the common man Article covering Copland development

- "A Time Machine trip to the mid-'90s", MacWorld article with screen snaps from Copland

- Apple Copland Reference Documentation

- Computer Chronicles—Mac Clones At the beginning of this episode there is a demo of the Copland OS

- Businessweek article on Copland