Contrapposto

Contrapposto (Italian pronunciation: [kontrapˈposto]) is an Italian term that means counterpoise. It is used in the visual arts to describe a human figure standing with most of its weight on one foot so that its shoulders and arms twist off-axis from the hips and legs. This gives the figure a more dynamic, or alternatively relaxed appearance. It can also be used to refer to multiple figures which are in counter-pose (or opposite pose) to one another. It can further encompass the tension as a figure changes from resting on a given leg to walking or running upon it (so-called ponderation). The leg that carries the weight of the body is known as the engaged leg, the relaxed leg is known as the free leg.[1] Contrapposto is less emphasized than the more sinuous S Curve, and creates the illusion of past and future movement.[2]

Contrapposto was an extremely important sculptural development, for its appearance marks the first time in Western art that the human body is used to express a psychological disposition. The balanced, harmonious pose of the Kritios Boy suggests a calm and relaxed state of mind, an evenness of temperament that is part of the ideal of man represented.

From this point onwards Greek sculptors went on to explore how the body could convey the whole range of human experience, culminating in the desperate anguish and pathos of Laocoön and His Sons (1st century CE) in the Hellenistic period.

History

Classical

The first known statue to use contrapposto is Kritios Boy, c. 480 BC,[3] so called because it was once attributed to the sculptor Kritios. It is possible, even likely, that earlier bronze statues had used the technique, but if they did, they have not survived and Kenneth Clark called the statue "the first beautiful nude in art".[4] The statue is a Greek marble original and not a Roman copy.

Prior to the introduction of contrapposto, the statues that dominated ancient Greece were the archaic kouros (male) and the kore (female). Contrapposto has been used since the dawn of classical western sculpture. According to the canon of the Classical Greek Sculptor Polykleitos in the 4th century BC, it is one of the most important characteristics of his figurative works and those of his successors, Lysippos, Skopas, etc. The Polykletian statues – for example, Discophoros (discus-bearer) and Doryphoros (spear-bearer) – are idealized athletic young men with the divine sense, and captured in contrapposto. In these works, the pelvis is no longer axial with the vertical statue as in the archaic style of earlier Greek sculpture before Kritios Boy.

Contrapposto can be clearly seen in the Roman copies of the statues of Hermes and Heracles. A famous example is the marble statue of Hermes with the infant Dionysus in Olympia by Praxiteles. It can also be seen in the Roman copies of Polyclitus's Amazon.

Greek Art emphasized humanism along with the human mind and the human body’s beauty.[5] Greek youths trained and competed in athletic contests in the nude. A great contribution to the contrapposto pose was the concept of a canon of proportions, in which mathematical properties are used to create proportions.[6]

Renaissance

Classical contrapposto was revived in the Renaissance by the Italian artists Donatello and Leonardo da Vinci, followed by Michelangelo, Raphael and other artists of the High Renaissance. One of the major achievements of the Italian Renaissance was the re-discovery of contrapposto, although in Mannerism it became greatly over-used.

Modern times

The technique continues to be widely employed in sculpture.

Examples

The Venus de Milo depicts an S Curve body shape. Greek, c. 130–100 BC.

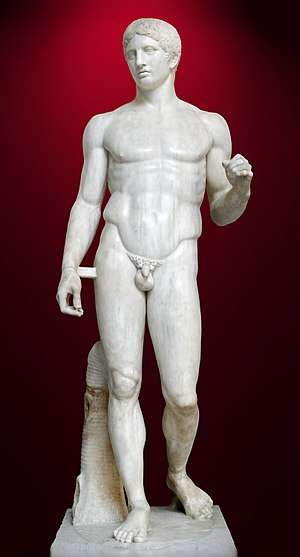

The Venus de Milo depicts an S Curve body shape. Greek, c. 130–100 BC. A marble copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, an early example of classical contrapposto. The original bronze is lost.

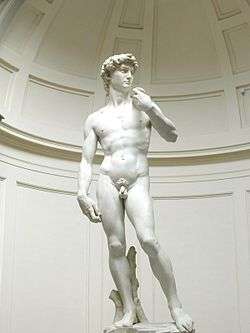

A marble copy of the Doryphoros of Polykleitos, an early example of classical contrapposto. The original bronze is lost. David, by Michelangelo, 1501–04. The shoulders of the figure are seen to angle in one direction, the pelvis in another.

David, by Michelangelo, 1501–04. The shoulders of the figure are seen to angle in one direction, the pelvis in another. Leda and the Swan, copy by Cesare da Sesto after a lost original by Leonardo da Vinci, 1515–20, Oil on canvas, Wilton House, England.

Leda and the Swan, copy by Cesare da Sesto after a lost original by Leonardo da Vinci, 1515–20, Oil on canvas, Wilton House, England.

See also

References and sources

- References

- ↑ Janson, H.W. (1995) History of Art. 5th edn. Revised and expanded by Anthony F. Janson. London: Thames & Hudson, p. 139. ISBN 0500237018

- ↑ "Contrapposto". Grove Encyclopedia Of Materials & Techniques In Art: 142–143. October 2008. ISBN 9780195313918.

- ↑ Honour, H. and J. Fleming, (2009) A World History of Art. 7th edn. London: Laurence King Publishing, p. 122. ISBN 9781856695848

- ↑ Clark, Kenneth. (2010) The Nude: A study in ideal form. New edition. London: The Folio Society, pp. 24-25.

- ↑ "Greek Humanism". www.webpages.uidaho.edu. Retrieved 2015-11-19.

- ↑ Stanley, Max (2010). "The 'Golden Canon' of book-page construction: proving the proportions geometrically". Journal of Mathematics & The Arts. 4 no. 3: 137–141.

- Sources

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Contrapposto. |

- Andrew Stewart, One Hundred Greek Sculptors: Their Careers and Extant Works Polykleitos of Argos, 16.72

- Polykleitos, The J. Paul Getty Museum (link broken)

- Polyclitus, 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica.