Connie Hawkins

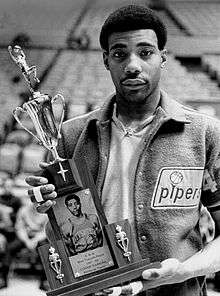

Hawkins with the ABA's most valuable player award in 1968 | |

| Personal information | |

|---|---|

| Born |

July 17, 1942 Brooklyn, New York |

| Died |

October 6, 2017 (aged 75) Phoenix, Arizona |

| Nationality | American |

| Listed height | 6 ft 8 in (2.03 m) |

| Listed weight | 210 lb (95 kg) |

| Career information | |

| High school | Boys (Brooklyn, New York) |

| NBA draft | 1964 / Undrafted |

| Playing career | 1961–1976 |

| Position | Power forward / Center |

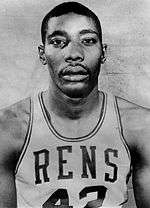

| Number | 42 |

| Career history | |

| 1961–1963 | Pittsburgh Rens |

| 1963–1967 | Harlem Globetrotters |

| 1967–1969 | Pittsburgh/Minnesota Pipers |

| 1969–1973 | Phoenix Suns |

| 1973–1975 | Los Angeles Lakers |

| 1975–1976 | Atlanta Hawks |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career ABA and NBA statistics | |

| Points | 11,528 (18.7 ppg) |

| Rebounds | 5,450 (8.8 rpg) |

| Assists | 2,556 (4.1 apg) |

| Stats at Basketball-Reference.com | |

| Basketball Hall of Fame as player | |

Cornelius "Connie" Lance Hawkins (July 17, 1942 – October 6, 2017) was an American basketball player in American Basketball League (ABL), American Basketball Association(ABA) and National Basketball Association (NBA), Harlem Globetrotter, Harlem Wizard and New York City playground legend. It was on the New York City courts that he earned his nickname, The Hawk. Hawkins was inducted into the Naismith Basketball Hall of Fame in 1992.

Early years

Hawkins was born in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn, where he attended Boys High School. Hawkins soon became a fixture at Rucker Park, a legendary outdoor court where he battled against some of the best players in the world.[1]

High school

Hawkins did not play much until his junior year at Boys High. Hawkins was All-City first team as a junior as Boys went undefeated and won New York's Public Schools Athletic League (PSAL) title in 1959. During his senior year he averaged 25.5 points per game, including one game in which he scored 60, and Boys again went undefeated and won the 1960 PSAL title. Hawkins then signed a scholarship offer to play at the University of Iowa.

College and investigation into point-shaving

During Hawkins' freshman year at Iowa, he was a victim of the hysteria surrounding a point-shaving scandal that had started in New York City. Hawkins' name surfaced in an interview conducted with an individual who was involved in the scandal. While some of the conspirators and characters involved were known to or knew Hawkins, none – including the New York attorney at the center of the scandal, Jack Molinas – had ever sought to involve Hawkins in the conspiracy. Hawkins had borrowed $200 from Molinas for school expenses, which his brother Fred repaid before the scandal broke in 1961.[2] The scandal became known as the 1961 college basketball gambling scandal.

Despite the fact that Hawkins could not have been involved in point-shaving (as a freshman, due to NCAA rules of the time, he was ineligible to participate in varsity-level athletics), he was kept from seeking legal counsel while being grilled by New York City detectives who were investigating the scandal.[3]

Expulsion from Iowa and ABL/Globetrotter/ABA years

As a result of the investigation, despite never being arrested or indicted, Hawkins was expelled from Iowa. He was effectively blackballed from the college ranks; no NCAA or NAIA school would offer him a scholarship. NBA commissioner J. Walter Kennedy let it be known that he would not approve any contract for Hawkins to play in the league. At the time, the NBA had a policy barring players who were even remotely involved with point-shaving scandals. As a result, when his class was eligible for the draft in 1964, no team selected him. He went undrafted in 1965 as well before being formally banned from the league in 1966.[2][4]

With the major professional basketball league having blackballed him, Hawkins played one season for the Pittsburgh Rens of the American Basketball League (ABL) and was named the league's most valuable player. After that league folded in the middle of the 1962–63 season, Hawkins spent four years performing with the Harlem Globetrotters.[5]

During the time Hawkins was traveling with the Globetrotters, he filed a $6 million lawsuit against the NBA, claiming the league had unfairly banned him from participation and that there was no substantial evidence linking him to gambling activities. Hawkins's lawyers suggested that he participate in the new American Basketball Association (ABA) as a way to show that he was talented enough to participate in the NBA.[6]

Hawkins joined the Pittsburgh Pipers in the inaugural 1967–68 season of the ABA, leading the team to a 54–24 regular season record and the 1968 ABA championship.[7] Hawkins led the ABA in scoring that year and won both the ABA's regular season and playoff MVP awards.

The Pipers moved to Minnesota for the 1968–69 season, and injuries limited Hawkins to 47 games. Hawkins had surgery on his knee. The Pipers made the playoffs despite injuries to their top four players, but were eliminated in the first round of the playoffs.

In the light of several major media pieces, notably in Life Magazine, establishing the dubious nature of the evidence connecting Hawkins to gambling, the NBA concluded it was unlikely to successfully defend the lawsuit and elected to settle after the 1968–69 season.

The league paid Hawkins a cash settlement of nearly $1.3 million, and assigned his rights to the expansion Phoenix Suns. He would be assigned to the Suns as a result of the them winning a coin toss over the Seattle SuperSonics.[8] Although the Pipers made a cursory effort to re-sign him, playing in the NBA had been a longtime ambition for Hawkins and he quickly signed with the Suns.

NBA career

In 1969, Hawkins hit the ground running in his first season with the Phoenix Suns, when he played 81 games and averaged 24.6 points, 10.4 rebounds and 4.8 assists per game. In the final game of his rookie season, Connie had 44 points, 20 rebounds, 8 assists, 5 blocks and 5 steals. The Suns finished third in the Western Conference, but were knocked out by the Los Angeles Lakers in a seven-game Western Conference Finals series in which Hawkins carried the Suns against a team that had future Hall of Famers Wilt Chamberlain, Elgin Baylor and Jerry West. For the series, Hawkins averaged 25 points, 14 rebounds and 7 assists per game.

Hawkins missed 11 games due to injury during the 1970–71 season, averaging 21 points per game. He matched those stats the next year, and was the top scorer on a per-game basis for the Suns in the 1971–72 season. He averaged only 16 points per game for the Suns in the 1972–73 season, and was traded to the Lakers for the next season.

Injuries limited his production in the 1974–75 season, and Hawkins finished his career after the 1975–76 season, playing for the Atlanta Hawks.

Milestones

Connie Hawkins was named to the ABA's All-Time Team.

Due to knee problems, Hawkins played in the NBA for only seven seasons. He was an All-Star from 1970 to 1973 and was named to the All-NBA First Team in the 1969–70 season. His no. 42 jersey was retired by the Suns.

Despite being unable to play in the NBA when he was in his prime, Hawkins' performances throughout the ABL, ABA and NBA helped get him get inducted into the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame in 1992.[9]

Personal life

The Hawkins' story up to 1971 is documented in the biography, "Foul" by David Wolf, ISBN 978-0030860218[10]

In a skit for NBC's Saturday Night Live in 1975, Hawkins played against singer Paul Simon in a one-on-one game accompanied by Simon's song "Me and Julio Down by the Schoolyard." The skit was presented as a schoolyard challenge between the two and had Simon winning, despite the disparity in height between the two men (Simon at 5 ft 3 in, Hawkins at 6 ft 8 in).[11][12]

One of Hawkins' nephews is Jim McCoy Jr., who scored a school-record 2,374 career points for the UMass Minutemen basketball team from 1988 to 1992.[13][14] He was the grandfather of Shawn Hawkins, who played professional basketball internationally and was a two-time scoring champion in Taiwan's Super Basketball League (SBL).[15]

Hawkins retired in Phoenix, Arizona and worked in community relations for the Suns[16] [17]for many years until his death on October 6, 2017, at the age of 75; no cause was given.[18]

References

- ↑ "Connie Hawkins". CNN.

- 1 2 Flatter, Ron. "Layups: More Info on Connie Hawkins". ESPN. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ Flatter, Ron (August 31, 2000). "Connie Hawkins: Flying Outside". espn.go.com. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ↑ "Connie Hawkins Bio". NBA.com. Turner Sports Interactive, Inc. Retrieved May 1, 2010.

- ↑ Moreland, Thomas (July 15, 2010), "'Foul! The Connie Hawkins Story' Is a Great Read for Hoops Fans", Bleacher Report

- ↑ David Wolf,. Foul! The Connie Hawkins Story. New York: Holt, Rinehart and Winston. ISBN 0-03-086021-0.

- ↑ Simonich, Milan (2008-03-31). "Pittsburgh had its basketball kings for a day in '68". Pittsburgh Post-Gazette.

- ↑ https://valleyofthesuns.com/2017/10/05/50-50-history-phoenix-suns-1969-70/

- ↑ Goldstein, Richard (October 7, 2017), "Connie Hawkins, Electrifying N.B.A. Forward Banned in His Prime, Dies at 75", The New York Times

- ↑ https://www.amazon.com/Foul-Connie-Hawkins-Story-David/dp/0030860210/ref=pd_sbs_14_1?_encoding=UTF8&pd_rd_i=0030860210&pd_rd_r=P0SK8N03E9GT80YTHM5S&pd_rd_w=2WQow&pd_rd_wg=HrUoL&psc=1&refRID=P0SK8N03E9GT80YTHM5S

- ↑ "SNL Transcripts:Paul Simon: 10/18/75: Weekend Update with Chevy Chase". snltranscripts.jt.org. Retrieved January 1, 2012.

- ↑ "Paul Simon (I) – Biography". IMDB. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ↑ Burris, Joe (7 February 1992). "When McCoy cries 'Uncle' ... UMass star gets Hall of Fame help from Connie Hawkins". The Boston Globe.

- ↑ "UMass Men's Basketball Record Book" (PDF). UMass Athletics. Retrieved 26 January 2012.

- ↑ "SBL History". Taiwan Hoops. June 16, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2017.

- ↑ http://www.nydailynews.com/archives/news/connie-hawkins-no-cards-article-1.847024

- ↑ http://www.foxnews.com/sports/2017/10/07/former-suns-great-connie-hawkins-dies-at-age-75.ht

- ↑ https://www.nytimes.com/2017/10/07/obituaries/connie-hawkins-dead.html

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Connie Hawkins. |

- Career statistics and player information from Basketball-Reference.com

- Basketball Hall of Fame profile

- ESPN list of the Top 10 High School athletes of all time

- Connie Hawkins bio on NBA.com