Commonwealth of Nations membership criteria

Commonwealth of Nations membership criteria are the corpus of requirements that members and prospective members must meet to be allowed to participate in the Commonwealth of Nations. The criteria have been altered by a series of documents issued over the past eighty-two years.

The most important of these documents were the Statute of Westminster (1931), the London Declaration (1949), the Singapore Declaration (1971), the Harare Declaration (1991), the Millbrook Commonwealth Action Programme (1995), the Edinburgh Declaration (1997), and the Kampala Communiqué (2007). New members of the Commonwealth must abide by certain criteria that arose from these documents, the most important of which are the Harare principles and the Edinburgh criteria.

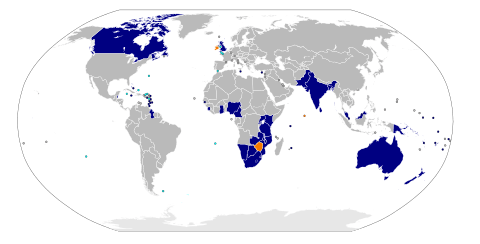

The Harare principles require all members of the Commonwealth, old and new, to abide by certain political principles, including democracy and respect for human rights. These can be enforced upon current members, who may be suspended or expelled for failure to abide by them. To date, Fiji, Nigeria, Pakistan, and Zimbabwe have been suspended on these grounds; Zimbabwe later withdrew.

The foremost of the Edinburgh criteria requires new members to have either constitutional or administrative ties to at least one current member of the Commonwealth of Nations. Traditionally, new Commonwealth members had ties to the United Kingdom. The Edinburgh criteria arose from the 1995 accession of Mozambique, at the time the only member that was never part of the British Empire (in whole or part). The Edinburgh criteria have been reviewed, and were revised at the 2007 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting, allowing the admission of Rwanda at the 2009 Meeting.[1]

History

Founding documents

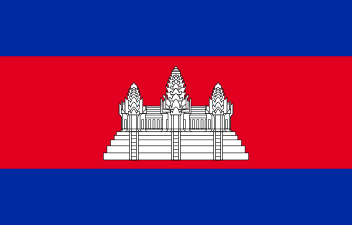

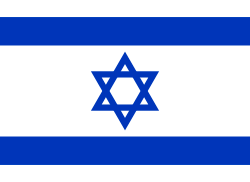

The formation of the Commonwealth of Nations is dated back to the Statute of Westminster, an Act of the British Parliament passed on 11 December 1931. The Statute established the independence of the Dominions, creating a group of equal members where, previously, there was one (the United Kingdom) paramount. The solitary condition of membership of the embryonic Commonwealth was that a state be a Dominion. Thus, the independence of Pakistan (1947), India (1947), and Sri Lanka (1948) saw the three countries join the Commonwealth as independent states that retained the king as head of state. On the other hand, Burma (1948) and Israel (1948) did not join the Commonwealth, as they chose to become republics. In 1949 the Commonwealth chose to regard Ireland as no longer being a member when Ireland repealed legislation under which the King had played a role in its diplomatic relations with other states, although the Irish government’s view was that Ireland had not been a member for some years.[2]

With India on the verge of promulgating a republican constitution, the 1949 Commonwealth Prime Ministers Conference was dominated by the impending departure of over half of the Commonwealth's population. To avoid such a fate, Canadian Prime Minister Louis St. Laurent proposed that republics be allowed to remain in the Commonwealth, provided that they recognise King George VI as 'Head of the Commonwealth'. Known as the London Declaration, this agreement thus established the only formalised rule as being that members must recognise the Head of the Commonwealth. The arrangement prompted suggestions that other countries, such as France,[3] Israel, and Norway,[4] join. However, until Western Samoa joined in 1970, only recently independent countries would accede.

Singapore Declaration

The first statement of the political values of the Commonwealth of Nations was issued at the 1961 conference, at which the members declared that racial equality would be one of the cornerstones of the new Commonwealth, at a time when the organisation's ranks were being swelled by new African and Caribbean members. The immediate result of this was the withdrawal of South Africa's re-application, which it was required to lodge before becoming a republic, as its government's apartheid policies clearly contradicted the principle.

Further political values and principles of the Commonwealth were affirmed in Singapore on 22 January 1971, at the first Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (CHOGM). The fourteen points clarified the political freedom of its members, and dictated the core principles of the Commonwealth: world peace, liberty, human rights, equality, and free trade.[5] However, neither the terms nor the spirit of the Declaration were binding, and several openly flouted it; despite little conformity, only Fiji was ever expelled for breaching these tenets (on 15 October 1987, following the second coup of that year).[6]

Harare Declaration

The Harare Declaration, issued on 20 October 1991 in Harare, Zimbabwe, reaffirmed the principles laid out in Singapore, particularly in the light of the ongoing dismantling of apartheid in South Africa. The Declaration put emphasis on human rights and democracy by detailing these principles once more:

| “ |

|

” |

Millbrook Programme

The Millbrook Commonwealth Action Programme, issued on 12 November 1995 at the Millbrook Resort, near Queenstown, New Zealand, clarified the Commonwealth's position on the Harare Declaration. The document introduced compulsion upon its members, with strict guidelines to be followed in the event of breaching its rules. These included but were not limited to expulsion from the Commonwealth. Adjudication was left to the newly created Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group (CMAG).[8]

At the same CHOGM, the Programme was enforced for the first time, as Nigeria was suspended. On 19 December 1995, the CMAG found that the suspension was in line with the Programme, and also declared its intent on enforcing the Programme in other cases (particularly Sierra Leone and The Gambia).[9] On 29 May 1999, the day after the inauguration of Nigeria's first democratically elected President since the end of military rule, Olusẹgun Ọbasanjọ, the country's suspension was lifted, on the advice of the CMAG.[10]

Edinburgh criteria

In 1995, Mozambique joined the Commonwealth, becoming the first member to have never had a constitutional link with the United Kingdom or another Commonwealth member. Concerns that this would allow open-ended expansion of the Commonwealth and dilute its historic ties prompted the 1995 CHOGM to launch the Inter-Governmental Group on Criteria for Commonwealth Membership, to report at the 1997 CHOGM, to be held in Edinburgh, Scotland. The group decided that, in future, new members would be limited to those with constitutional association with an existing Commonwealth member.[11]

In addition to this new rule, the former rules were consolidated into a single document. They had been prepared for the High Level Appraisal Group set up at the 1989 CHOGM, but not publicly announced until 1997.[12] These requirements, which remain the same today, are that members must:

- accept and comply with the Harare principles.

- be fully sovereign states.

- recognise Queen Elizabeth II as the Head of the Commonwealth.[13]

- accept the English language as the means of Commonwealth communication.

- respect the wishes of the general population vis-à-vis Commonwealth membership.[14]

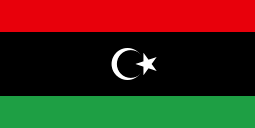

Kampala review

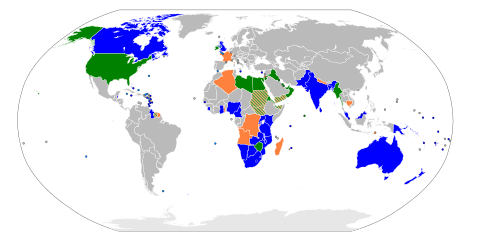

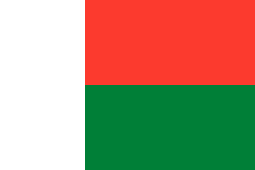

On the advice of Secretary-General Don McKinnon, the 2005 CHOGM, held in Valletta, Malta, decided to re-examine the Edinburgh criteria. The Committee on Commonwealth Membership reported at the 2007 CHOGM, held in Kampala, Uganda.[15] According to Don McKinnon, the members of the Commonwealth decided in principle to expand the membership of the organisation to include countries without linkages to the Commonwealth, but Eduardo del Buey stated that it would still take some time until the criteria are reformed. Outstanding applications as of the 2007 meeting included former Belgian colony Rwanda (application submitted in 2003 and approved in 2009), the former French colonies of Algeria and Madagascar, and the former British colony of Yemen and condominium of Sudan.[16]

The revised requirements stated that:[17]

- (a) an applicant country should, as a general rule, have had a historic constitutional association with an existing Commonwealth member, save in exceptional circumstances;

- (b) in exceptional circumstances, applications should be considered on a case-by-case basis;

- (c) an applicant country should accept and comply with Commonwealth fundamental values, principles, and priorities as set out in the 1971 Declaration of Commonwealth Principles and contained in other subsequent Declarations;

- (d) an applicant country must demonstrate commitment to: democracy and democratic processes, including free and fair elections and representative legislatures; the rule of law and independence of the judiciary; good governance, including a well-trained public service and transparent public accounts; and protection of human rights, freedom of expression, and equality of opportunity;

- (e) an applicant country should accept Commonwealth norms and conventions, such as the use of the English language as the medium of inter-Commonwealth relations, and acknowledge Queen Elizabeth II as the Head of the Commonwealth; and

- (f) new members should be encouraged to join the Commonwealth Foundation, and to promote vigorous civil society and business organisations within their countries, and to foster participatory democracy through regular civil society consultations

Rwanda became the 54th nation to join the Commonwealth at the 2009 CHOGM. It became the second country (after Mozambique) not to have any historical ties with the United Kingdom. Rwanda had been a colony of Germany in the 19th century and of Belgium for the first half of the 20th century.[18] Later ties with France were severed during the 1994 Rwandan Genocide. President Paul Kagame also accused it of supporting the killings and expelled a number of French organisations from the country.[19] In recent years, English has replaced French as the official language in parts of Rwanda.[20] Prime Minister of Malaysia Najib Tun Razak stated that Rwanda's application "was boosted by its commitment towards democracy as well as the values espoused by the Commonwealth".[21] Consideration for its admission was also seen as an "exceptional circumstance" by the Commonwealth Secretariat.[22]

Prospective members

Secessionist movements and other territories

- Northern Ireland:[36] constituent country of the United Kingdom, a member since the Commonwealth's foundation.

.svg.png)

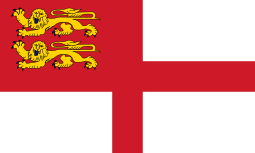

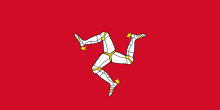

- Crown dependencies – The

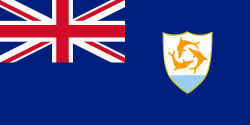

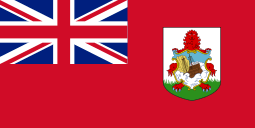

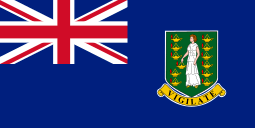

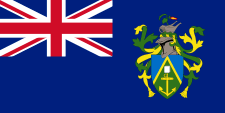

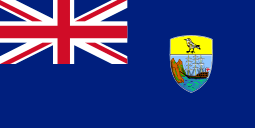

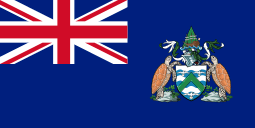

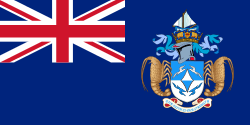

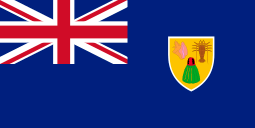

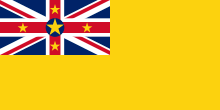

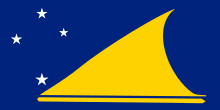

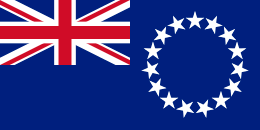

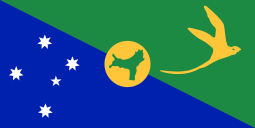

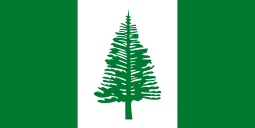

- The inhabited British overseas territories of

_Islands.svg.png)

Footnotes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Howden, Daniel (26 November 2009). "The Big Question: What is the Commonwealth's role, and is it relevant to global politics?". The Independent. London.

- ↑ Ireland’s status was a matter of controversy and debate between 1936 and 1949.

- ↑ "France and UK considered 1950s 'merger'". London: Guardian Unlimited. 15 January 2007. Retrieved 22 July 2007.

- ↑ "Kongebesøk i øyriket" (in Norwegian). Aftenposten. 26 October 2005. Archived from the original on 10 March 2007. Retrieved 15 December 2008.

- ↑ "Singapore Declaration of Commonwealth Principles 1971". Commonwealth Secretariat. 22 January 1971. Archived from the original on 11 May 2008. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Fiji Rejoins the Commonwealth". Commonwealth Secretariat. 30 September 1997. Archived from the original on 1 November 2004. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Harare Commonwealth Declaration, 1991". Commonwealth Secretariat. 1991-10-20. Retrieved 2006-09-16.

- ↑ "The Millbrook Commonwealth Action Programme on the Harare Declaration, 1995". Commonwealth Secretariat. 12 November 1995. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "First Meeting of the Commonwealth Ministerial Action Group on the Harare Declaration". Commonwealth Secretariat. 20 December 1995. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Nigeria Resumes Full Commonwealth Membership". Commonwealth Secretariat. 18 May 1999. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "Edinburgh Communique, 1997". Commonwealth Secretariat. 27 October 1997. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- 1 2 McIntyre, W. David (April 2008). "The Expansion of the Commonwealth and the Criteria for Membership". Round Table. 97 (395): 273–85. doi:10.1080/00358530801962089.

- ↑ Collinge, John (July 1996). "Criteria for Commonwealth Membership". Round Table. 85 (339): 279–86. doi:10.1080/00358539608454314.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 te Velde-Ashworth, Victoria (10 October 2005). "The future of the modern Commonwealth: Widening vs. deepening?". Commonwealth Policy Studies Unit. Archived from the original (doc) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ "2005 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting: Final Communiqué". Commonwealth Secretariat. 27 November 2005. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 16 September 2006.

- ↑ Osike, Felix (24 November 2007). "Rwanda membership delayed". New Vision. Archived from the original on 23 January 2013. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ 2007 Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting: final communiqué Archived 16 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Kron, Josh (28 November 2009). "Rwanda Joins Commonwealth". The New York Times. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Rwanda seeks to join Commonwealth". BBC News. 21 December 2006. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ Ross, Will (27 November 2009). "What would the Commonwealth do for Rwanda?". BBC News. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ Muin, Abdul; Majid, Abdul (29 November 2009). "Commonwealth Accepts Rwanda's Membership Bid". Bernama. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ "Rwanda: Joining the Commonwealth". The New Times. AllAfrica. 27 November 2009. Retrieved 29 November 2009.

- ↑ Gaaki Kigambo (2012-10-13). "Burundi plans to become Commonwealth member". Theeastafrican.co.ke. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ "Alkatiri Raises Possibility of Commonwealth Membership". East Timor and Indonesia Action Network. 6 November 2001. Retrieved 5 November 2006.

- ↑ Thomson, Mike (15 January 2007). "When Britain and France nearly married". BBC. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ Mole, Stuart (July 1998). "Issues of Commonwealth membership". Round Table. 87 (347): 307–12. doi:10.1080/00358539808454426.

- 1 2 "Israel and Palestine could join the Commonwealth". Daily Telegraph. 2006-12-17. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

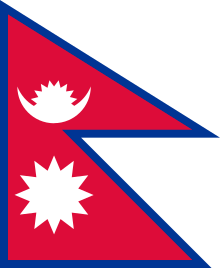

- ↑ "Nepal urged to join Commonwealth," The Himalayan Times, 19 January 2016. Retrieved 2 April 2018.

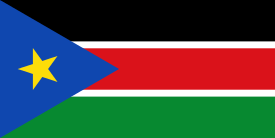

- ↑ "South Sudan on Track to Join Commonwealth". Shimronletters.blogspot.com. 2011-05-22. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ "South Sudan Launches Bid to Join Commonwealth". Gurtong.net. 2011-07-08. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ Suriname plans to join the Commonwealth

- ↑ "Suriname eyeing membership of Commonwealth". Stabroeknews.com. 2012-06-14. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ "Worldwide Priority: Strengthening Guyana's participation in the Commonwealth and providing guidance to Suriname as it considers applying for membership". Gov.uk. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ "Togo exploring application to join the Commonwealth". Thecommonwealth.org. 2017-03-17. Retrieved 2018-06-05.

- ↑ https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/05/zimbabwe-applies-rejoin-commonwealth-180522062016470.html

- ↑ 1972 Cabinet Papers: Repartition - Still a Threat - By Ciaran Mulholland Archived 13 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine., Quote:Making Northern Ireland "an independent state within the Commonwealth" was also under active consideration.

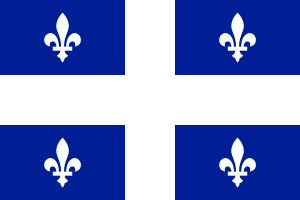

- ↑ Burns, John F. (21 February 1992). "Montreal Journal; A Sovereign Quebec, He Says, Needn't Be Separe". The New York Times. Retrieved 21 June 2009.

[Mr. Parizeau] has even suggested that a sovereign Quebec might join the Commonwealth, the group of nations that were formerly British colonies.

- ↑ YOUR SCOTLAND, YOUR VOICE - Summary of the SNP White Paper on Scottish Independence, quote:Scotland would also be able to play a role in other global groups such as...the Commonwealth

- ↑ Independent Wales would be 39% richer, claims ex-MP, quote:Plaid has a long-term ambition for an independent Wales within the EU

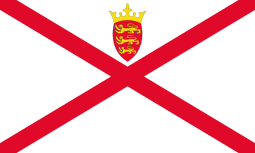

- ↑ "Written evidence from States of Jersey". Chief Minister of Jersey. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "The role and future of the Commonwealth". House of Commons. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

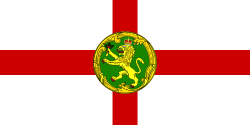

- ↑ "Written evidence from the States of Guernsey". Policy Council of Guernsey. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ↑ "Appendix B: The Commonwealth of Nations" Library of Congress Federal Research Division country studies: Area handbook series - Caribbean islands. Retrieved 10 August 2013.

External links

- Velde-Ashworth, Victoria. "Commonwealth Membership and the Patterson Commission Report: In the light of the Kampala Communiqué" (doc). Commonwealth Policy Studies Unit. Retrieved 6 December 2009.