Collectible card game

A collectible card game (CCG), also called a trading card game (TCG) or many other names,[note 1] is a kind of strategy card game that was created in 1993 and consists of specially designed sets of playing cards. These cards use proprietary artwork or images to embellish the card. CCGs may depict anything from fantasy or science fiction genres, horror themes, cartoons, or even sports. Game text is also on the card and is used to interact with the other cards in a strategic fashion. Games are commonly played between two players, though multiplayer formats are also common. Players may also use dice, counters, card sleeves, or play mats to complement their gameplay.

CCGs can be played with or collected, and often both. Generally, a CCG is initially played using a starter deck. This deck may be modified by adding cards from booster packs, which contain around 8 to 15 random cards.[2] As a player obtains more cards, they may create new decks from scratch. When enough players have been established, tournaments are formed to compete for prizes.

Successful CCGs typically have thousands of unique cards, often extended through expansion sets that add new mechanics. Magic: The Gathering, the first developed and most successful, has over 17,000 distinct cards.[3] By the end of 1994, Magic: The Gathering had sold over 1 billion cards,[4] and between the time period of 2008 to 2016 sold over 20 billion.[5] Other successful CCGs include Yu-Gi-Oh! which sold over 25 billion cards as of March 2011,[6] and Pokémon which has sold over 25 billion cards as of March 2018.[7] Other notable CCGs have come and gone, including Legend of the Five Rings, Star Wars, Lord of the Rings, Vampire: The Eternal Struggle, and World of Warcraft. Many other CCGs were produced but had little or no commercial success.[8]

Recently, digital collectible card games (DCCGs) have gained popularity, spurred by the success of Hearthstone.[9] DCCGs do not use physical cards and instead use digital representations, with newer DCCGs foregoing card images altogether by using basic icons.

Overview

A collectible card game (CCG) is generally defined as a game where players acquire cards into a personal collection from which they create customized decks of cards and challenge other players in matches.[10] Players usually start by purchasing a starter deck that is ready to play, but additional cards are obtained from randomized booster packs or by trading with other players.[11] The goal of most CCGs is to beat your opponent by crafting customized decks that play to synergies of card combinations. Refined decks will try to account for randomness as well as opponent's actions, by using the most complementary and efficient cards possible.

The exact definition of what makes a CCG is varied, as many games are marketed under the "collectible card game" moniker. The basic definition requires the game to resemble trading cards in shape and function, be mass-produced for trading or collectibility, and have rules for strategic gameplay.[12][13] The definition of CCGs is further refined as being a card game in which the player uses his own deck with cards primarily sold in random assortments. If every card in the game can be obtained by making a small number of purchases, or if the manufacturer does not market it as a CCG, then it is not a CCG.[14]

CCGs can further be designated as living or dead games. Dead games are those CCGs which are no longer supported by their manufacturers and have ceased releasing expansions. Living games are those CCGs which continue to be published by their manufacturers. Usually this means that new expansions are being created for the game and official game tournaments are occurring in some fashion.[14]

Card games that should not be mistaken for CCGs:

- Deck-Building Games - Construction of the deck is the main focus of gameplay.[15]

- Collectible Common-Deck Card Games are card games where players share a common deck rather than their own personal deck. Consequently, no customization of decks nor trading occurs, and no metagame is developed. There is little to no interest in collecting the cards.[14]

- Non-Collectible Customizable Card Games are those games where each player has their own deck, but no randomness occurs when acquiring the cards. Many of these games are sold as complete sets. A few were intended to have booster packs, but those were never released.[16] This category may also be referred to as an ECG, or Expandable Card Game.[17] This category also includes LCGs.

- Living Card Games (LCGs)[note 2] - LCGs are a type of non-collectible customizable card game (see above), and a registered trademark of Fantasy Flight Games.[18] They don't use the randomized booster packs like CCGs and instead are bought in a single purchase.[19] LCGs are known for costing much less as they are not a collectible.[20]

Gameplay mechanics

Each CCG system has a fundamental set of rules that describes the players' objectives, the categories of cards used in the game, and the basic rules by which the cards interact. Each card will have additional text explaining that specific card's effect on the game. They also generally represent some specific element derived from the game's genre, setting, or source material. The cards are illustrated and named for these source elements, and the card's game function may relate to the subject. For example, Magic: The Gathering is based on the fantasy genre, so many of the cards represent creatures and magical spells from that setting. In the game, a dragon is illustrated as a reptilian beast and typically has the flying ability and higher combat stats than smaller creatures.

The bulk of CCGs are designed around a resource system by which the pace of each game is controlled. Frequently, the cards which constitute a player's deck are considered a resource, with the frequency of cards moving from the deck to the play area or player's hand being tightly controlled. Relative card strength is often balanced by the number or type of resources needed in order to play the card, and pacing after that may be determined by the flow of cards moving in and out of play. Resources may be specific cards themselves, or represented by other means (e.g. tokens in various resource pools, symbols on cards, etc.).

Unlike traditional card games such as poker or crazy eights in which a deck's content is limited and pre-determined, players select which cards will compose their deck from any available cards printed for the game. This allows a CCG player to strategically customize their deck to take advantage of favorable card interactions, combinations and statistics. While a player's deck can theoretically be of any size, a deck of fortyfive or sixty cards is considered the optimal size, for reasons of playability, and has been adopted by most CCGs as an arbitrary 'standard' deck size. Deck construction may also be controlled by the game's rules. Some games, such as Magic: the Gathering, limit how many copies of a particular card can be included in a deck; such limits force players to think creatively when choosing cards and deciding on a playing strategy.

Each match of a CCG is generally one-on-one with another opponent, but many CCGs have variants for more players. Typically, the goal of a match is to play cards that reduce the opponent's life total to zero before the opponent can do the same. Some CCGs provide for a match to end if a player has no more cards in their deck to draw. During a game, players usually take turns playing cards and performing game-related actions. The order and titles of these steps vary between different CCGs, but the following are typical:

- Ready phase — A player's own in-play cards are readied for the upcoming turn.

- Draw phase — The player draws one or more cards from his or her own deck. This is necessary in order to circulate cards in players' hands.

- Main phase — The player uses the cards in hand and in play to interact with the game or to gain and expend resources. Some games allow for more than one of these phases.

- Combat phase — This typically involves some sort of attack against the other player, which that player defends against using their own cards. Such a phase is the primary method for victory in most games.

- End of turn — The player discards to the game's maximum hand size, if it has one, and end of turn effects occur.

Broadly, cards played can either represent a resource, a character or minion, spells or abilities that directly impact players or creatures, or objects that have other effects on the game state. Many CCGs have rules where opposing players can react to the current player's turn; an example is casting a counter-spell to an opponent's spell to cancel it such as in Magic: The Gathering. Other CCGs do not have such direct reaction systems, but allow players to cast face-down cards or "traps" that automatically trigger based on actions of the opposing player.

Distribution

Specific game cards are most often produced in various degrees of scarcity, generally denoted as fixed (F), common (C), uncommon (U), and rare (R). Some games use alternate or additional designations for the relative rarity levels, such as super-, ultra-, mythic- or exclusive rares. Special cards may also only be available through promotions, events, purchase of related material, or redemption programs. The idea of rarity borrows somewhat from other types of collectible cards, such as baseball cards, but in CCGs, the level of rarity also denotes the significance of a card's effect in the game, i.e., the more powerful a card is in terms of the game, the greater its rarity.[21] A powerful card whose effects were underestimated by the game's designers may increase in rarity in later reprints. Such a card might even be removed entirely from the next edition, to further limit its availability and its effect on gameplay.

Most collectible card games are distributed as sealed packs containing a subset of the available cards, much like trading cards. The most common distribution methods are:

- Starter deck — An introductory deck that contains enough cards for one player. It may contain random or a pre-determined selection of cards.

- Starter set — An introductory product that contains enough cards for two players. The card selection is usually pre-determined and non-random.

- Theme deck or Tournament deck — Most CCGs are designed with opposing factions, themes, or strategies. A theme deck is composed of pre-determined cards that fit these motifs.

- Booster packs — The most common distribution method. Booster packs for CCGs usually contain 8 to 15 cards.[2]

History of the Collectible Card Game

Prehistory

Regular card games have been around since at least the 1300s, but in 1993 a "new kind of card game" appeared.[22] It was different because the player could not buy all the cards at once. Players would first buy starter decks and then later be encouraged to buy booster packs to expand their selection of cards. What emerged was a card game that players collected and treasured but also played with.[22] The very first collectible card game created was Magic: The Gathering, invented by Richard Garfield, and patented by Wizards of the Coast in 1993.[12][14][22][23][24][25][26] It's considered the most successful CCG and many other companies have tried to emulate its success.[27][28] It was based on Garfield's game Five Magics from 1982.[29] Allen Varney of Dragon Magazine claimed the designer of Cosmic Encounter, Peter Olotka, spoke of the idea of designing a collectible card game as early as 1979.[30]

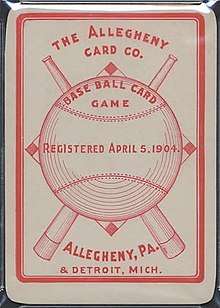

The Base Ball Card Game, a prototype from 1904, is a notable precursor to CCGs because it had a few similar qualities but it never saw production to qualify it as a collectible card game.[31] It is not known if the game was intended to be a standalone product or something altogether different like Top Trumps.[8] The game consisted of a limited 112 cards and never saw manufacture past the marketing stage.[32] In 1951, Topps released the Baseball Card Game that resembled CCGs because the game cards were sold in random packs and were collectible, however the game required no strategic play to operate.[29] To play the game, players used a randomized deck to migrate their characters around a baseball diamond. Interaction between the two players was limited to who scored the most points and was otherwise a solitaire-like function since players could not play simultaneously but in tandem.[33] This game seemed to be a followup of a game from 1947 called Batter Up by Ed-u-Cards Corp. The game was not sold in random packs but instead the entirety of the game could be obtained with one purchase. It utilized the same baseball diamond rules that Topps adopted in 1951.[33] Other notable entries that resemble and predate the CCG are Strat-O-Matic, Nuclear War, BattleCards, and Illuminati.[14] When designing Magic: The Gathering, Garfield borrowed elements from the board game Cosmic Encounter which also used cards for game play.[22]

Wizards of the Coast and Magic: The Gathering (1993-1994)

Prior to the advent of the CCG, the market for alternative games was dominated by role-playing games (RPG), in particular Dungeons & Dragons by TSR. Wizards of the Coast (Wizards), a new company formed in Peter Adkison's basement in 1990, was looking to enter the RPG market with its series called The Primal Order which converted characters to other RPG series. After a suit from Palladium Books which could have financially ruined the company, Wizards acquired another RPG called Talislanta. This was after Lisa Stevens joined the company in 1991 as vice president after having left White Wolf. Through their mutual friend Mike Davis, Adkison met Richard Garfield who at the time was a doctoral student. Garfield and Davis had an idea for a game called RoboRally and pitched the idea to Wizards of the Coast in 1991, but Wizards did not have the resources to manufacture it and instead challenged Garfield to make a game that would pay for the creation of RoboRally. This game would require minimal resources to make and only about 15–20 minutes to play.[14]

In December 1991, Garfield had a prototype for a game called Mana Clash, and by 1993 he established Garfield Games to attract publishers and to get a larger share of the company should it become successful. Originally, Mana Clash was designed with Wizards in mind, but the suit between Palladium Books and Wizards was still not settled. Investment money was eventually secured from Wizards and the name Mana Clash was changed to Magic: The Gathering. The ads for it first appeared in Cryptych, a magazine that focused on RPGs. On the July 4th weekend of 1993, the game premiered at the Origins Game Fair in Fort Worth, Texas. In the following month of August, the game was released and sold out its initial print run of 2.6 million cards immediately creating more demand. Wizards quickly released new iterations of the core set, called Beta (7.3 million card print run) and Unlimited (35 million card print run) in an attempt to satisfy orders as well as to fix small errors in the game. December also saw the release of the first expansion called Arabian Nights. With Magic: The Gathering still the only CCG on the market, it released another expansion called Antiquities which experienced collation problems. Another core set iteration named Revised was released shortly after that. Demand was still not satiated as the game grew by leaps and bounds. Legends was released in mid-1994 and no end was in sight for the excitement over the new CCG.[14][34]

CCG craze (mid-1994-1995)

What followed was the CCG craze. Magic was so popular that game stores could not keep it on their shelves. More and more orders came for the product, and as other game makers looked on they realized that they had to capitalize on this new fad. The first to do so was TSR who rushed their own game Spellfire into production and was released in June 1994. Through this period of time, Magic was hard to obtain because production never met the demand. Store owners placed large inflated orders in an attempt to circumvent allocations placed by distributors. This practice would eventually catch up to them when printing capacity met demand coinciding with the expansion of Fallen Empires released in November 1994. Combined with the releases of 9 other CCGs, among them Galactic Empires, Decipher's Star Trek, On the Edge, and Super Deck!. Steve Jackson Games, which was heavily involved in the alternative game market, looked to tap into the new CCG market and figured the best way was to adapt their existing Illuminati game. The result was Illuminati: New World Order which followed with two expansions in 1995 and 1998. Another entry by Wizards of the Coast was Jyhad. The game sold well, but not nearly as well as Magic, however it was considered a great competitive move by Wizard as Jyhad was based on one of the most popular intellectual properties in the alternative game market which kept White Wolf from aggressively competing with Magic. By this time however, it may have been a moot point as the CCG Market had hit its first obstacle: too much product. The overprinted expansion of Magic's Fallen Empires threatened to upset the relationship that Wizards had with its distributors as many complained of getting too much product, despite their original over-ordering practices.[14][35][36]

In early 1995, the GAMA Trade Show previewed upcoming games for the year. One out of every three games announced at the show was a CCG. Publishers other than game makers were now entering the CCG market such as Donruss, Upper Deck, Fleer, Topps, Comic Images, and others. The CCG bubble appeared to be on everyone's mind. Too many CCGs were being released and not enough players existed to meet the demand. In 1995 alone, 38 CCGs entered the market, among them the most notable being Doomtrooper, Middle-earth, OverPower, Rage, Shadowfist, Legend of the Five Rings, and SimCity. Jyhad saw a makeover and was renamed as Vampire: The Eternal Struggle to distance itself from the Islamic term jihad as well as to get closer to the source material.[14] The Star Trek CCG from Decipher was almost terminated after disputes with Paramount announced that the series would end in 1997. But by the end of the year, the situation was resolved and Decipher regained the license to the Star Trek franchise along with Deep Space Nine, Voyager and the movie First Contact.[14]

Enthusiasm from manufacturers was very high, but by the summer of 1995 at Gen Con, retailers had noticed CCG sales were lagging. The Magic expansion Chronicles released in November and was essentially a compilation of older sets. It was maligned by collectors and they claimed it devalued their collections. Besides this aspect, the market was still reeling from too much product as Fallen Empires still sat on shelves alongside newer Magic expansions like Ice Age. The one new CCG that retailers were hoping to save their sales, Star Wars, wasn't released until very late in December. By then, Wizards of the Coast, the lead seller in the CCG market had announced a downsizing in their company and it was followed by a layoff of over 30 jobs. The excess product and lag in sales also coincided with an 8 month long gap in between Magic: The Gathering's expansions, the longest in its history.[14][35]

In Hungary, Hatalom Kártyái Kártyajáték, or HKK, was released in 1995 and was inspired by Magic: The Gathering. HKK was later released in the Czech Republic. HKK is still being made.[37][38]

Stabilization and consolidation (1996-1997)

In early 1996, the CCG market was still reeling from its recent failures and glut of product, including the release of Wizards' expansion Homelands which was rated as the worst Magic expansion to date. The next two years would mark a "cool off" period for the over-saturated CCG market. Additionally, manufacturers slowly came to understand that having a CCG was not enough to keep it alive. They also had to support organized players through tournaments. Combined with a new dichotomy between collectors and players especially among Magic players, more emphasis was placed on the game rather than the collectibility of the cards.[14]

Plenty more CCGs were introduced in 1996, chief among them were BattleTech, The X-Files, Mythos, and Wizard's very own Netrunner. Many established CCGs were in full swing releasing expansions every few months, but even by this time, many CCGs from only two years ago had already died. TSR had ceased production of Spellfire and attempted another collectible game called Dragon Dice which failed shortly after being released.[14]

On June 3rd of 1997, Wizards of the Coast announced that it had acquired TSR and its Dungeons & Dragons property which also gave them control of Gen Con.[39] Wizards now had its long sought role-playing game, and it quickly discontinued all plans to continue producing Dragon Dice as well as any hopes of resuming production of the Spellfire CCG. Decipher was now sanctioning tournaments for their Star Trek and Star Wars games. Star Wars was also enjoying strong success from the recently rereleased Star Wars Special Edition films. In fact, the CCG would remain the second best selling CCG until the introduction of Pokémon in 1999.[14]

Wizards continued acquiring properties and bought Five Rings Publishing Group, Inc., creators of the Legend of the Five Rings CCG, Star Trek: The Next Generation collectible dice game, and the soon to be released Dune CCG, on June 26.[40] Wizards also acquired Andon Unlimited which by association gave them control over the Origins Convention. By September, Wizards was awarded a patent for its "Trading Card Game." Later in October, Wizards announced that it would seek royalty payments from other CCG companies. Allegedly, only Harper Prism announced its intention to pay these royalties for its game Imajica. Other CCGs acknowledged the patent on their packaging.[14][16][35]

1997 saw a slow down in the release of new CCG games. Only 7 new games came out, among them: Dune: Eye of the Storm, Babylon 5, Shadowrun, Imajica and Aliens/Predator. Babylon 5 saw moderate success for a few years before its publisher Precedence succumbed to a nonrenewal of its license later on in 2001. Also in 1997, Vampire: The Eternal Struggle ceased production. However, Wizards of the Coast attempted to enter a more mainstream market with the release of a watered-down version of Magic, called Portal. Its creation is considered a failure along with its follow up Portal Second Age released in 1998.[14]

Wizards of the Coast dominates, Hasbro steps in (1998-1999)

By February 1998, one out of every two CCGs sold was Magic: the Gathering. Only 7 new CCGs were introduced that year, all but two being Wizards of the Coast product. C-23, Doomtown, Hercules: The Legendary Journeys, Legend of the Burning Sands and Xena: Warrior Princess were those five, and only Doomtown met with better than average reviews before its run was terminated and the rights returned to Alderac. C-23, Hercules, and Xena were all a part of a new simplified CCG system Wizards had created for beginners. Called the ARC System, it had four distinct types of cards: Resource, Character, Combat, and Action. The system also utilized the popular "tapping" mechanic of Magic: The Gathering. This system was abandoned shortly afterwards.[14]

Despite limited success or no success at all in the rest of the CCG market, Magic had recovered and Wizards learned from its lessons of 1995 and early 1996. Players still enjoyed the game and were gobbling up its latest expansions of Tempest, Stronghold, Exodus and by year's end, Urza's Saga which added new enthusiasm to Magic's fanbase in light of some of the cards being "too powerful."[14]

In early 1999, Wizards released the Pokémon TCG to the mass market. The game benefited from the Pokémon fad also of that year. At first there wasn't enough product to meet demand. Some retailers perceived the shortage to be, in part, related to Wizards's recent purchase of the Game Keeper stores where it was assumed they received Pokémon shipments more often than non-affiliated stores. By the summer of 1999, the Pokémon TCG became the first CCG to outsell Magic: The Gathering. The success of Pokémon brought renewed interest to the CCG market and many new companies began pursuing this established customer base. Large retail stores such as Walmart and Target began carrying CCGs and by the end of September, Hasbro was convinced on its profitability and bought Wizards of the Coast for $325 million.[14][16]

A small selection of new CCGs also arrived in 1999, among them Young Jedi, Tomb Raider, Austin Powers, 7th Sea and The Wheel of Time.[14]

Transitions and refining of the market (2000)

By 2000, the ups and downs of the CCG market was old hat to its retailers. They foresaw Pokémon's inevitable fall from grace as the fad reached its peak in April of that year. The panic associated with the overflooding of the CCGs from 1995 and 1996 was absent and the retailers withstood the crash of Pokémon. Yet CCGs benefited from the popularity of Pokémon and they saw an uptick in the number of CCGs released and an overall increased interest in the genre. Pokémon's mainstream success in the CCG world also highlighted an increasing trend of CCGs being marketed with existing intellectual properties, especially those with an existing television show, such as a cartoon. New CCGs introduced in 2000 included notable entries in Sailor Moon, The Terminator, Digi-Battle, Dragon Ball Z Collectible Card Game, Magi-Nation and X-Men. Vampires: The Eternal Struggle resumed production in 2000 after White Wolf regained full rights and released the first new expansion in three years called Sabbat War. Wizards of the Coast introduced a new sports CCG called MLB Showdown as well.[14]

Decipher released its final chronological expansion of the original Star Wars trilogy called Death Star II and would continue to see a loss in sales as interest waned in succeeding expansions, and their Star Wars license was not being renewed. Mage Knight was also released this year and would seek to challenge the CCG market by introducing miniatures into the mix. Though not technically a CCG, it would target the same player base for sales. The real shake up in the industry however, came when Hasbro laid off more than 100 workers at Wizards of the Coast and ended its attempts at an online version of the game when it sold off their interactive division. Coinciding with this turn of events was Peter Adkisson's decision to resign and Lisa Stevens whose job ended when The Duelist magazine (published by Wizards of the Coast) was cancelled by the parent company. With Adkisson went Wizards' acquirement of Gen Con and the Origins Convention went to GAMA. Hasbro also ceased production of Legends of the Five Rings in 2000 and it resumed production when it was sold to Alderac in 2001.[14][35]

Franchise trends continue (2001-2002)

As seen in 2000, the years 2001 and 2002 continued on with the CCG market being less likely to take chances on new and original intellectual properties, but instead it would invest in CCGs that were based off existing franchises. Cartoons, movies, television, and books influenced the creation of such CCGs as Harry Potter, The Lord of the Rings, A Game of Thrones, Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Yu-Gi-Oh! and two Star Wars CCGs: Jedi Knights and a rebooted Star Wars TCG, by Decipher and Wizards of the Coast. They followed the demise of the original Star Wars CCG by Decipher in December of 2001, but they would see very little interest and eventually the two games were cancelled. Other niche CCGs were also made, including Warlord and Warhammer 40,000.[14][16]

Upper Deck had its first hit with Yu-Gi-Oh! The game was known to be popular in Japan but until 2002 had not been released in the United States. The game was mostly distributed to big retailers, with hobby stores added to their distribution afterwards. By the end of 2002, the game was the top CCG even though it was no where near the phenomenon that Pokémon was. The card publisher Precedence produced a new CCG in 2001 based on the Rifts RPG by Palladium. Rifts had top of the line artwork but the size of the starter deck was similar in size to the RPG books. Precedence's other main CCG Babylon 5 ended its decent run in 2001 after the company lost its license. The game was terminated and the publisher later folded in 2002. The release of The Lord of the Rings CCG marked the release of the 100th new CCG since 1993, and 2002 also marked the release of the 500th CCG expansion for all CCGs. The Lord of the Rings CCG briefly beat out sales of Magic for a few months.[16]

Magic continued a steady pace releasing successful expansion blocks with Odyssey and Onslaught. Decipher released The Motion Pictures expansion for the Star Trek CCG, and also announced that it would be the last expansion for the game. Decipher then released the Second Edition for the Star Trek CCG which refined the rules, rebooted the game, and introduced new card frames. Collectible miniature games continued their effort to take a slice of the pie away from the CCG market with the releases of HeroClix and MechWarrior in 2002 but saw limited success.[16]

A second wave of new CCGs (2003-2005)

The next few years saw a large increase in the number of companies willing to start a new CCG. No small thanks to the previous successes of Pokémon and Yu-Gi-Oh!, many new CCGs entered the market, many of which tried to continue the trend of franchise tie-ins. Notable entries include The Simpsons, SpongeBob SquarePants, Neopets, G.I. Joe, Hecatomb, Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles and many others. Duel Masters was introduced to the United States after strong popularity in Japan the previous two years. Wizards of the Coast published it for a couple years before it was cancelled in the U.S. due to weak sales. Two Warhammer CCGs were released with Horus Heresy and WarCry. Horus Heresy lasted two years and was succeeded by Dark Millennium in 2005.

Also, two entries from Decipher were released, one that passed the torch from their Star Wars CCG to WARS. WARS kept most of the game play mechanics from their Star Wars game, but transferred them to a new and original setting. The game did not do particularly well, and after two expansions, the game was cancelled in 2005. The other new CCG was .hack//Enemy which won an Origins award. The game was also cancelled in 2005.[41]

Plenty of other CCGs were attempted by various publishers, many that were based on Japanese manga such as Beyblade, Gundam War, One Piece, Inuyasha, Zatch Bell!, Case Closed, and YuYu Hakusho. Existing CCGs were reformatted or rebooted including Dragon Ball Z as Dragon Ball GT and Digimon D-Tector as the Digimon Collectible Card Game.

An interesting CCG released by Upper Deck was called the Vs. System. It incorporated the Marvel and DC Comics universes and pitted the heroes and villains from those universes against one another. Similarly, the game UFS: The Universal Fighting System used characters from Street Fighter, Soul Calibur, Tekken, Mega Man, Darkstalkers, etc. This CCG was obtained by Jasco Games in 2010 and is currently still being made. Another CCG titled Call of Cthulhu was the spiritual successor to Mythos by the publisher Chaosium. Chaosium licensed the game to Fantasy Flight Games who produced the CCG.

Probably one of the biggest developments in the CCG market was the release of Magic's 8th Edition core set. It introduced a redesigned card border and it would later mark the beginning of a new play format titled Modern that utilized cards from this set onward. Another development was Pokémon, originally published by Wizards, was sold to Nintendo in June 2003. This would start a slow revival for the brand though never reaching the 1999 craze.

The CCG renaissance continues (2006-present)

The previous years influx of new CCGs continued into 2006. Riding on the success of the popular PC Game World of Warcraft, Blizzard Entertainment licensed Upper Deck to publish a TCG based on the game. The World of Warcraft TCG was born and was carried by major retailers but saw limited success until it was discontinued in 2013 prior to the release of Blizzard's digital card game Hearthstone. Following previous trends, Japanese-influenced CCGs continued to enter the market. These games were either based on cartoons or manga and included: Naruto, Avatar: The Last Airbender, Bleach, Rangers Strike and the classic series Robotech. Dragon Ball GT was rebooted once again in 2008 and renamed as Dragon Ball.

Many other franchises were made into CCGs with a few reboots. Notable ones included Cardfight!! Vanguard, Conan, Battlestar Galactica, Power Rangers, 24 TCG, Redakai, Monsuno, and others, as well as another attempt at Doctor Who in the United Kingdom and Australia. Publisher Alderac released City of Heroes CCG based on the City of Heroes PC game. Another video game, Kingdom Hearts for the PS2, was turned into the Kingdom Hearts TCG by Tomy.

A few other CCGs were released only in other countries and never made it overseas to English speaking countries, including Monster Hunter of Japan, and Vandaria Wars of Indonesia. By the end of 2008, trouble was brewing between Konami, who owned the rights to Yu-Gi-Oh! and its licensee Upper Deck. Meanwhile, strong sales continued with the three top CCGs of Pokémon, Yu-Gi-Oh!, and Magic: the Gathering. The Warhammer series Dark Millennium ended its run in 2007.

Magic: the Gathering saw a large player boom in 2009, with the release of the Zendikar expansion. The spike in the number of Magic players continued for a few years and leveled off by 2015.[42] Interest also developed with their multiplayer format called Commander. This increase in the player base created a finance speculation market. New players entering the market from 2009 to 2015 desired cards that were printed before 2009 and with smaller print runs. Demand outstripped quantity and prices of certain cards increased and speculators started to directly manipulate the Magic card market to their advantage. This eventually attracted the interest of the controversial figure Martin Shkreli, former CEO of Turing Pharmaceuticals, for a brief period of time.[43] Prices of cards from previous sets increased dramatically and the American market saw an influx of Chinese counterfeits capitalizing on the demand. This created a unique situation where the most desirable and expensive cards could be printed by counterfeiters, but not by the brand owner, due to a promise made with collectors back in 1996 and refined in 2011.[44][45] In 2015, Wizards of the Coast implemented more anti-counterfeit measures by introducing a holographic foil onto cards with specific rarities, in addition to creating a proprietary font.[46][47]

A rise in tie-in collectible card games continued with the introduction of the My Little Pony Collectible Card Game. It was licensed to Enterplay LLC by Hasbro and published on December 13, 2013.[48] The collectible cards, according to president Dean Irwin, proved to be moderately successful, so Enterplay reprinted the premiere release set mid-February 2014.[48] Other tie-in games released included the Final Fantasy Trading Card Game and Star Wars: Destiny. Force of Will was released in 2012 in Japan and in 2013 in English, but as an original intellectual property.

One of the longest running CCGs, Legend of the Five Rings, released its final set Evil Portents for free in 2015. After a 20 year run, the brand was sold to Fantasy Flight Games and released as a living card game.[49]

In March 2018, it was announced that PlayFusion and Games Workshop would team up to create a new Warhammer trading card game.[50]

Reception

In 1996 Luke Peterschmidt, designer of Guardians, remarked that unlike board game and RPG players, CCG players seem to assume they can only play one CCG at a time.[51] Often, the less mainstream CCGs will have localized sales success, in that some cities a CCG will be a success, but in others it will be a flop.[52]

Patent for "Trading Card Game Method of Play"

A patent originally granted in 1997 to Richard Garfield was for "a novel method of game play and game components that in one embodiment are in the form of trading cards" that includes claims covering games whose rules include many of Magic's elements in combination, including concepts such as changing orientation of a game component to indicate use (referred to in the Magic and Vampire: The Eternal Struggle rules as "tapping") and constructing a deck by selecting cards from a larger pool.[53] Garfield transferred the patent to Wizards of the Coast.[54] The patent has aroused criticism from some observers, who believe some of its claims to be invalid.[55] Peter Adkison, CEO of Wizards at the time, remarked that his company was interested in striking a balance between the "free flow of ideas and the continued growth of the game business" with "the ability to be compensated by others who incorporate our patented method of play into their games".[56] Adkison continued to say they "had no intention of stifling" the industry that originated from the "success of Magic."[56]

In 2003, the patent was an element of a larger legal dispute between Wizards of the Coast and Nintendo, regarding trade secrets related to Nintendo's Pokémon Trading Card Game. The legal action was settled out of court, and its terms were not disclosed.[57]

Embodiments of the invention

Details of the patent are as follows:

- 1. A method of playing games involving two or more players, the method being suitable for games having rules for game play that include instructions on drawing, playing, and discarding game components, and a reservoir of multiple copies of a plurality of game components, the method comprising the steps of:[56]

- A. Each player constructing their own library of a predetermined number of game components by examining and selecting game components from the reservoir of game components;[56]

- B. Each player obtaining an initial hand of a predetermined number of game components by shuffling the library of game components and drawing at random game components from the player's library of game components; and[56]

- C. Each player executing turns in sequence with other players by drawing, playing, and discarding game components in accordance with the rules until the game ends, said step of executing a turn comprises:[56]

- a. making one or more game components from the player's hand of game components available for play by taking the one or more game components from the player's hand and placing the one or more game components on a playing surface; and[56]

- b. bringing into play one or more of the available game components by: (i) selecting one or more game components ; and (ii) designating the one or more game components being brought into play by rotating the one or more game components from an original orientation to a second orientation.[56]

See also

Footnotes

- ↑ Collectible Card Games (CCG) may also be known as a Trading Card Game (TCG), Customizable Card Game, Expandable Card Game (ECG - see Age of Empires II) or simply as a Card Game. Terms such as "collectible" and "trading" are often used interchangeably because of copyrights and marketing strategies of game companies.[1]

- ↑ LCGs, or Living Card Games, are a registered trademark of Fantasy Flight Games.

References

- ↑ Frank, Jane (2012), Role-Playing Game and Collectible Card Game Artists : A Biographical Dictionary, pp. 2–3, retrieved 2014-11-22

- 1 2 Brown, Timothy (1999), Official Price Guide to Collectible Card Games, p. 505

- ↑ "Gatherer". Wizards of the Coast. Retrieved March 6, 2014. , the official Magic card database.

- ↑ Chalk, Titus (July 31, 2013), 20 Years Of Magic: The Gathering, A Game That Changed The World, retrieved August 11, 2013

- ↑ "Magic: the Gathering 25th anniversary Facts & Figures". Magic.Wizards.com. Retrieved 2018-02-09.

- ↑ "Yu-Gi-Oh! Card Game Breaks Guinness Record with 25.1 Billion Cards Sold New Series Available Worldwide". Konami Digital Entertainment. Konami. June 20, 2011.

- ↑ "Business Summary". Pokémon official website. The Pokémon Company. March 2018.

- 1 2 Unknown, Kai (2011-07-12), Collectible Card Games, retrieved 2013-08-12

- ↑ Minotti, Mike (January 28, 2017). "SuperData: Hearthstone trumps all comers in card market that will hit $1.4 billion in 2017". Venture Beat. Retrieved January 28, 2017.

- ↑ "Collectible Card Game". TvTropes.org. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ "Getting started with the Pokemon Trading Card Game (TCG) for parents". Virantha.com. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- 1 2 Williams, J. Patrick (2007-05-02), Gaming as Culture: Essays on Reality, Identity and Experience in Fantasy Games (PDF), retrieved 2013-08-11

- ↑ Board Game Terminology, 2012-01-27, retrieved 2013-08-12

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 Miller, John Jackson (2001), Scrye Collectible Card Game Checklist & Price Guide, p. 520.

- ↑ "So what exactly is a deck-building game anyway?". Destructoid.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Miller, John Jackson (2003), Scrye Collectible Card Game Checklist & Price Guide, Second Edition, p. 688.

- ↑ "Expandable Card Games (ECG), Trademarks & Patents (3 of 3)". PairofDiceParadise.com. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- ↑ "Choosing your Living Card Game". TheStar.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "The Living Card Game: Giving Collectible Card Games a Run for Their Money". BoardGameResource.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ "LCGs Top CCGs". ICV2.com. Retrieved 2017-12-20.

- ↑ Ham, Ethan. "Rarity and Power: Balance in Collectible Object Games". Gamestudies.org. Retrieved 2017-12-21.

- 1 2 3 4 Owens, Thomas S.; Helmer, Diana Star (1996), Inside Collectible Card Games, pp. 10–12.

- ↑ Long, Nick (2006-03-01), Understanding Magic: The Gathering - Part One: History, archived from the original on 2014-07-29, retrieved 2013-08-08

- ↑ Ching, Albert (2011-09-11), Card Game MAGIC: THE GATHERING Returns to Comics at IDW, retrieved 2013-08-11

- ↑ Kotha, Suresh (1998-10-19), Wizards of the Coast (PDF), retrieved 2013-08-11

- ↑ Stafford, Patrick (2014-05-24), Richard Garfield: King of the cards, retrieved 2014-06-05

- ↑ "Magic: The Gathering Fact Sheet" (PDF). Wizards of the Coast. 2009. Retrieved 2013-06-10.

- ↑ "First modern trading card game". Guinness World Records. 2013. Retrieved 2013-06-16.

- 1 2 Tumbusch, T. M.; Zwilling, Nathan (1995), Tomart's Photo Checklist & Price Guide to Collectible Card Games, Volume One, p. 88.

- ↑ Varney, Allen (January 1994). "Role-playing Reviews" (PDF). Dragon Magazine. TSR Inc. pp. 66–67. Retrieved 2017-12-19.

- ↑ "The Base Ball Card Game". Retrieved 2013-08-08.

- ↑ Lipset, Lew (2000), "The Hobby Insider - Recollecting the history of a baseball card game that never was", Sports Collectors Digest, p. 50.

- 1 2 unknown, toppcat (2013-03-28), It's Cott To be Good!, retrieved 2013-08-12

- ↑ Moursund, Beth (2002), The Complete Encyclopedia of Magic: The Gathering, p. 720.

- 1 2 3 4 Appelcline, Shannon (2006-08-03), A Brief History of Game #1: Wizards of the Coast: 1990-Present, archived from the original on 2006-08-24, retrieved 2013-08-29

- ↑ Courtland, Hayden-William (n.d.), History of Spellfire, retrieved 2013-08-30

- ↑ "A Hatalom Kártyái Kártyajáték története - Beholder Fantasy". www.beholder.hu. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Mi is az a Hatalom Kártyái Kártyajáték? - Beholder Fantasy". www.beholder.hu. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ↑ "Wizards of the Coast News", The Duelist (#19), p. 18, October 1997

- ↑ "Wizards of the Coast News", The Duelist (#19), p. 17, October 1997

- ↑ "Origins Award Winners (2003)". Academy of Adventure Gaming Arts & Design. Archived from the original on 2007-11-05. Retrieved 2007-10-02.

- ↑ Lennon, Ross (2015-03-20), Accumulated Knowledge 1 - Intro to History of Magic Finance, retrieved 2017-09-04

- ↑ Morris, David Z. (2016-07-10), Martin Shkreli is Getting Into Magic: the Gathering, and Gamers Are Conflicted, retrieved 2017-09-04

- ↑ Wizards of the Coast (2016-05-04), Official Reprint Policy, retrieved 2017-09-04

- ↑ EchoMtG, Magic Reserve List, retrieved 2017-09-04

- ↑ Andres, Chas (2014-01-13), Counterfeit Cards, retrieved 2017-09-04

- ↑ Styborski, Adam (2014-01-06), New Card Frame Coming in Magic 2015, retrieved 2017-09-06

- 1 2 "'MLP CCG' Trending in Hobby". ICV2. January 14, 2014. Retrieved August 4, 2014.

- ↑ Gordon, David (October 7, 2015), Dave of the Five Rings: Chapter Twenty-One, retrieved October 1, 2017

- ↑ PlayFusion. "PlayFusion and Games Workshop Join Forces to Create New Warhammer AR, Physical and Digital Trading Card Game". www.prnewswire.com. Retrieved 2018-03-31.

- ↑ "Inside the Industry - Reports on Trading Card Games", The Duelist (#12), p. 73, September 1996

- ↑ Varney, Allen (February 1997), "Inside the Industry", The Duelist (#15), p. 83

- ↑ US 5662332

- ↑ "Patently Confusing", The Duelist (#21), p. 85, January 1998

- ↑ Varney, Allen (2006-05-03). "The Year in Gaming". The Austin Chronicle. Archived from the original on 2011-08-09. Retrieved 2007-06-03.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Wizards of the Coast News", The Duelist (#21), p. 17, January 1998

- ↑ "Pokemon USA, Inc. and Wizards of the Coast, Inc. Resolve Dispute". Business Wire. 2003-12-29. Retrieved 2013-08-24.

Bibliography

- Miller, John Jackson; Greenholdt, Joyce (2003). Collectible Card Games Checklist & Price Guide (2nd ed.). Krause Publication. ISBN 0-87349-623-X.